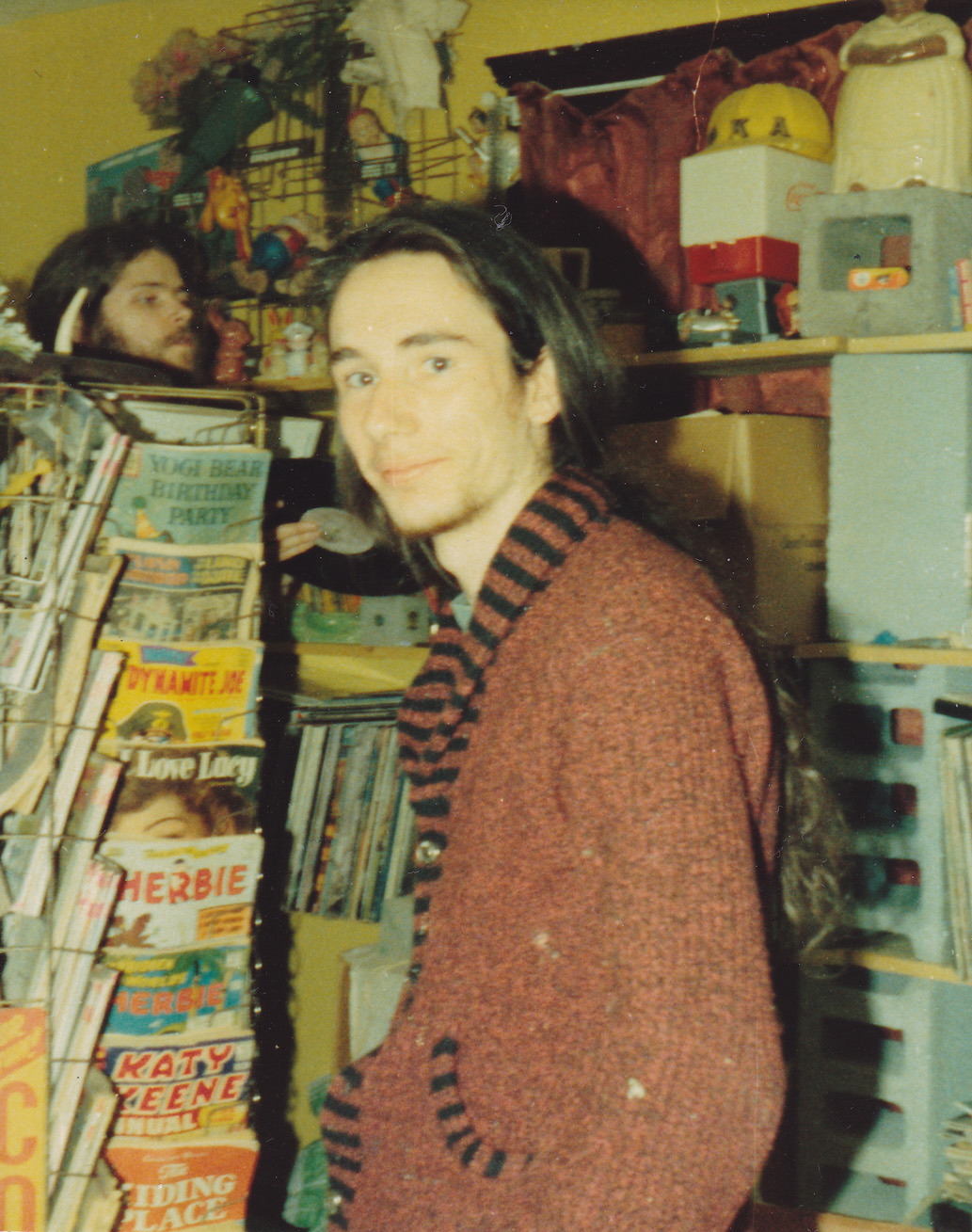

Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography

Michigan Stories has recently opened at the MSU Broad. Can you tell me a little about the exhibition?

The chief curator, Marc-Olivier Wahler wanted to show Mike Kelley and I together, I think because we came from there, and he and other Europeans are probably more familiar with our work than 99.9% of Michiganders are. There is a section on Destroy All Monsters, the noise band we co-founded with Cary Loren and Niagara way back in the mid-70s, as well as some of our collections of stuff and our art. I’m not sure how it all works together, but I’m not the curator.

“In the mid-70s we had no concept of success, either in the art world or music.”

You have previously said, “I realized I wasn’t naturally born to good taste”. Growing up in Michigan, at what point did you develop your understanding of what taste was?

My folks had a subscription to the New Yorker, which was pretty much the epitome of good taste aside from Charles Addams. Pop art and surrealism resonated with my teenage self and cubism and ab-ex didn’t. You’re supposed to outgrow the first two and mature into the second two, but I didn’t. Comic books were OK in my house because my father was into newspaper comics, but I had to sneak monster magazines in like they were porn, and they weren’t sold in Midland, so I had to accompany my sisters on clothes buying trips to Saginaw to furtively buy Famous Monsters, so my nerdy masculinity could flourish…

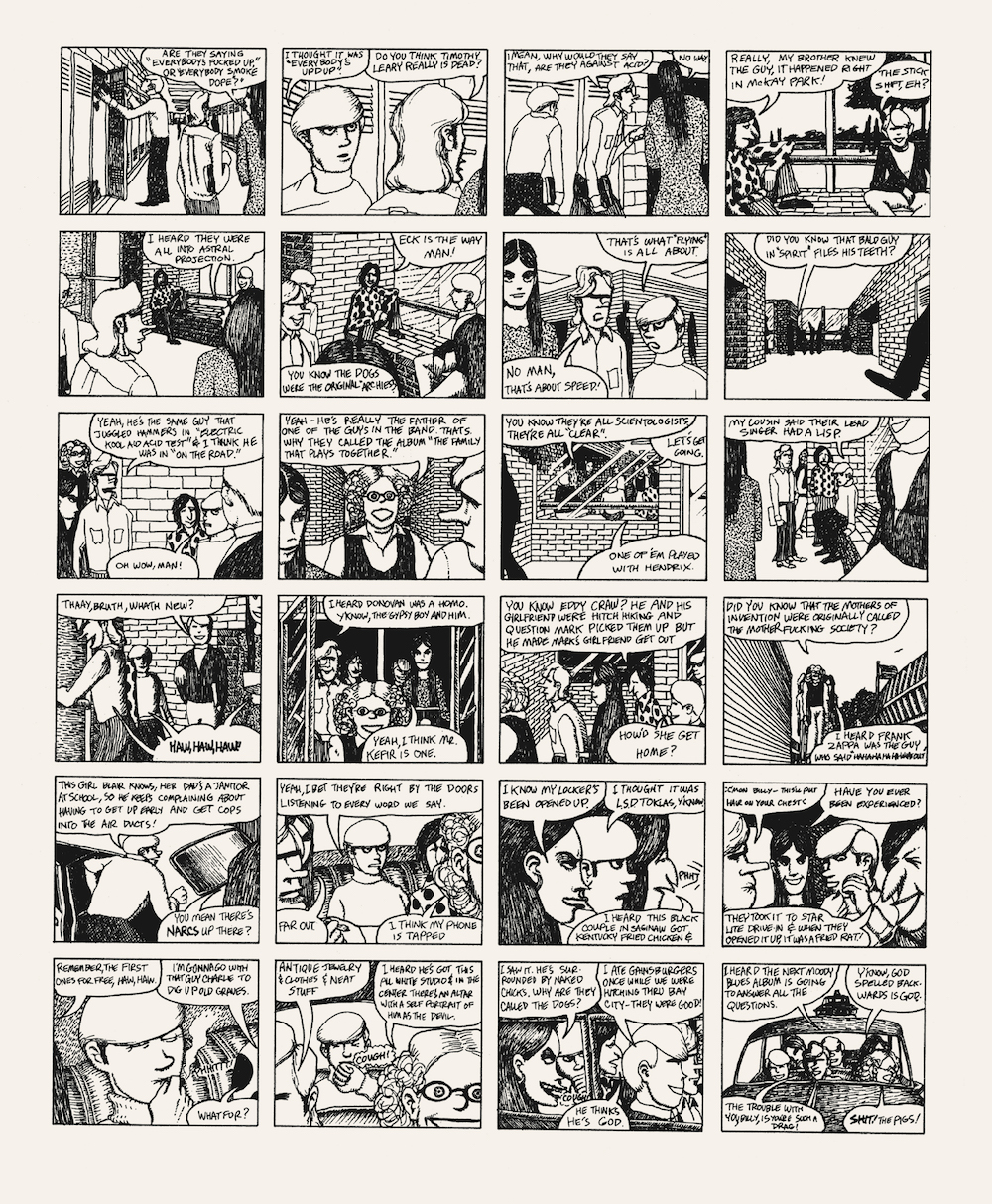

Courtesy Cary Loren

What was the first meeting between you and Mike Kelley like?

I remember running into Mike in the hall outside the figure drawing studio. We both looked weird, so I guess our weird-dar was operating. I remember a conversation about whether Jethro Tull was a legit art band circa Thick as a Brick, but memory is faulty.

During your time with Destroy All Monsters you performed but hardly recorded. Was the project more about creating performances rather than music that could be sold and consumed?

Actually, we recorded way more than we performed. I had bad stage fright and little musical talent, and there was no place for a band like us in A2, which was mostly roots, rock and bar blues bands at the time. Those few parties we played at weren’t too happy about it. Our later version, which happened in the 90s was more methodical and performance oriented. The original was really two different bands, Mike, Cary and me making drones and noise pieces, then Cary and Niagara doing goth Velvet Underground songs about death. In the mid-70s we had no concept of success, either in the art world or music. The band was like a parody of a rock band.

Photostat, courtesy the artist

Your art collection, The Hidden World, will also be exhibited in the show. What are you looking for in the thrift store paintings you collect?

The Hidden World is my collection of didactic art, mostly mass-produced, mostly religious pamphlets. I offered thrift store paintings as well, but with two artists and DAM in the show, I guess wall space was limited. Way back in high school I came across a book called The Voice of Venus at the local used bookstore. It was by the founder of Unarius, a California-based space religion. At the University of Michigan I started coming across Christian propaganda, much of it clumsily aimed at hippies. There are also political comics, scientific diagrams, crackpot flyers. We are borrowing items from fellow collectors in this version, Unarius costumes, Richard Shavers ephemera and art, and more of Szukalski’s scientific observations, so it should be overflowing with new food for thought. When it showed in New York, the ugly underbelly of America was surprising to many, but Michigan is a motherlode of Trumpian America, so the artefacts should feel quite at home there. Many of the pamphlets that I’ve collected are quaint precursors to the modern output of Alex Jones and Breitbart. The future of collecting is online, where the ephemera is truly ephemeral.

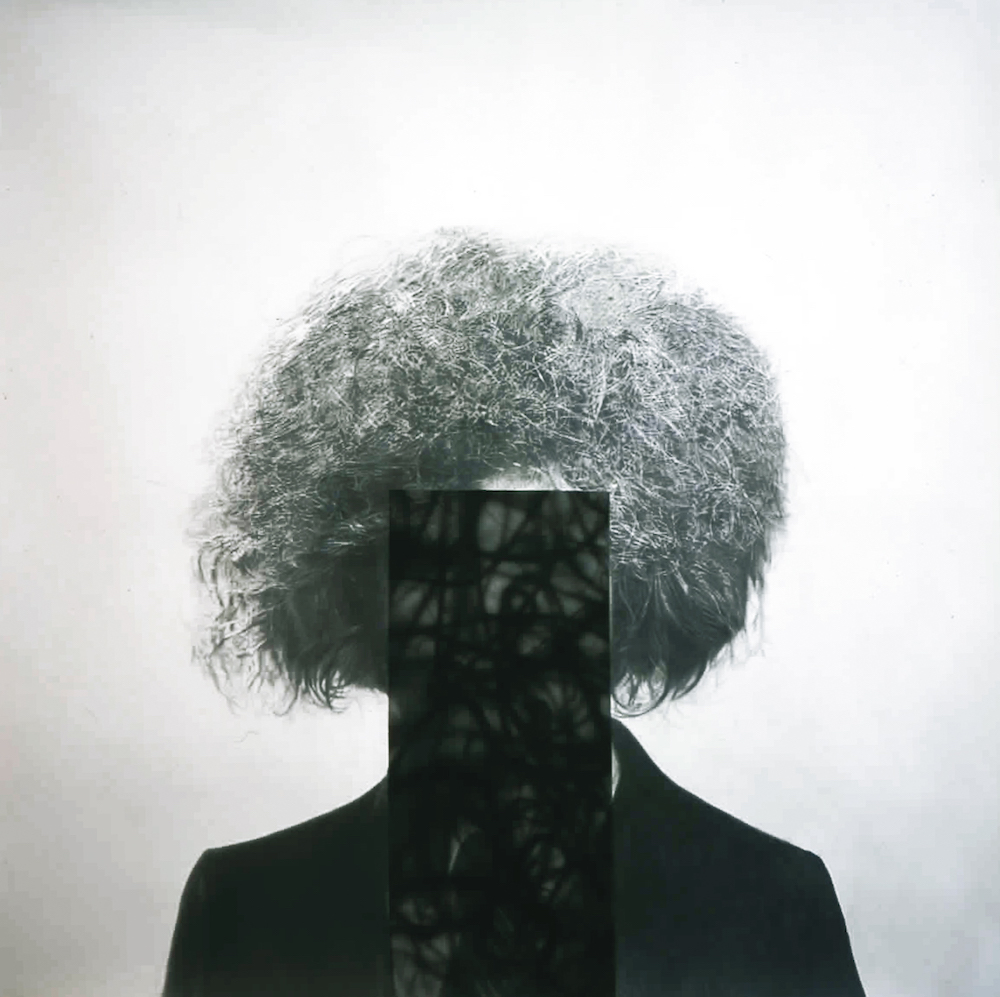

Destroy All Monsters Collective (Mike Kelley, Cary Loren, Jim Shaw), Greetings from Detroit, 2000

Courtesy the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts, Los Angeles. Art © Destroy All Monsters Collective. All Rights Reserved/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

A lot of your painting references the aesthetics of sci-fi and comic book art. What are some of your favourite comic books?

My taste in comics is mostly stuck before 1965 when I stopped reading comics code approved comics, but of course, the undergrounds like Crumb, Williams and Justin Green made their way into my pantheon. Later I glommed onto Alan Moore, Dan Clowes and Chester Brown, knowing there are many other good contemporary commix folks out there, but who has the time to read so much? Lately, I’ve been buying up as many precode horror reprints as I can. They are kind of like a corollary to all the CD collections of blues and world music 78s I listen to, a repository of a lost and romanticized world, except they are two different time periods, united in the poor pay the artists received and a belief in the devil.

Courtesy Cranford Collection

Your works are often packed with references to a mixture of pop culture and “high” culture. Is it important that people recognize and understand all these points of reference when they look at your work?

It’s important that the referents be there, but not that they be understood as I intend them. You can lead an eyeball to art but you can’t make it come up with your interpretation of your meanings without an explanatory diagram. Part of the art comes in how the “public” interacts with the artwork. It is important that the work draws the viewer in.

“In some cases, I suppose the cult leader is just a slimy son of a bitch.”

How important is humour when making art?

There is usually a mordant, gallows humour to my artwork, a bit of embarrassment in the conjunction of images. I think being friends with Mike made the humour aspect acceptable to me, also, taking Baldessari’s grad seminar exposed one to a lot of jokes.

Courtesy the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts, Los Angeles. Art © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

In the late nineties you developed your fictional religion O-ism, and you have spoken a lot about your interest in religions born in the US such as Mormonism. Mike Kelley was also known for creating systems of understanding or belief that gave the feeling of making sense but were actually completely fictional, for example in his early performance Confusion. Does this work seek to question what it takes for something to be considered a “real” religion, or is it more about the whole idea of “truth” in general?

I was interested initially in how a different religion would lead to different aesthetics, but the more I dug into the topic, the more I felt I had to take religion seriously. Another inspiration I had was while I waited in the doctor’s office at a Scientologist run cheap clinic (called the Shaw Clinic) in East Hollywood, where I happened to hear a sincere conversation between the doctors about some ethical spasm in the church, which made me interested in how one deals with a crisis of faith in what, from the outside, looks ridiculous and cultish. When I read Going Clear, I was shocked to read that my doctor at that little clinic, Dr Denk, was L Ron Hubbard’s personal physician, so I guess he weathered the storm of faith well.

What do you think it is that drives the creation of new religions?

In some cases, I suppose the cult leader is just a slimy son of a bitch, like “Moses”/ Father David of the Children of God. But mostly I imagine they are truly infected with the belief they are talking to God, something that can be stimulated with electrodes or psychedelic drugs.