You live and work in London, but recently travelled to Brazil to work with elite gymnasts. What attracted you to Brazilian gymnasts?

My interest in elite gymnastics (and also dog breeding) stems from an attraction to subcultures—worlds populated by people with obsession, commitment and passion, worlds which might say something to us about the larger world we live in. I’ve always been fascinated by the history and politics of international gymnastics, which often provides a barometer of the changing world order.

While in Brazil I made sound recordings with the Brazilian artistic gymnastic teams in the run-up to the Rio de Janeiro Olympics, preparing for a future sound and light installation. I also developed new works with the rhythmic gymnastic squad of the Vila Olímpica da Mangueira, a social project in a Rio favela. Gymnastics has traditionally been a “white” sport, pioneered in Europe from classical roots, and with enduring influences from the artistically driven Eastern Bloc. I was interested to see how the endeavours of the Brazilian gymnasts might reflect the more turbulent social and political environment of a nation in crisis; and what, if any, influence might be apparent from Brazil’s vibrant cultural life, and the Brazilian obsession with the body, dance and movement.

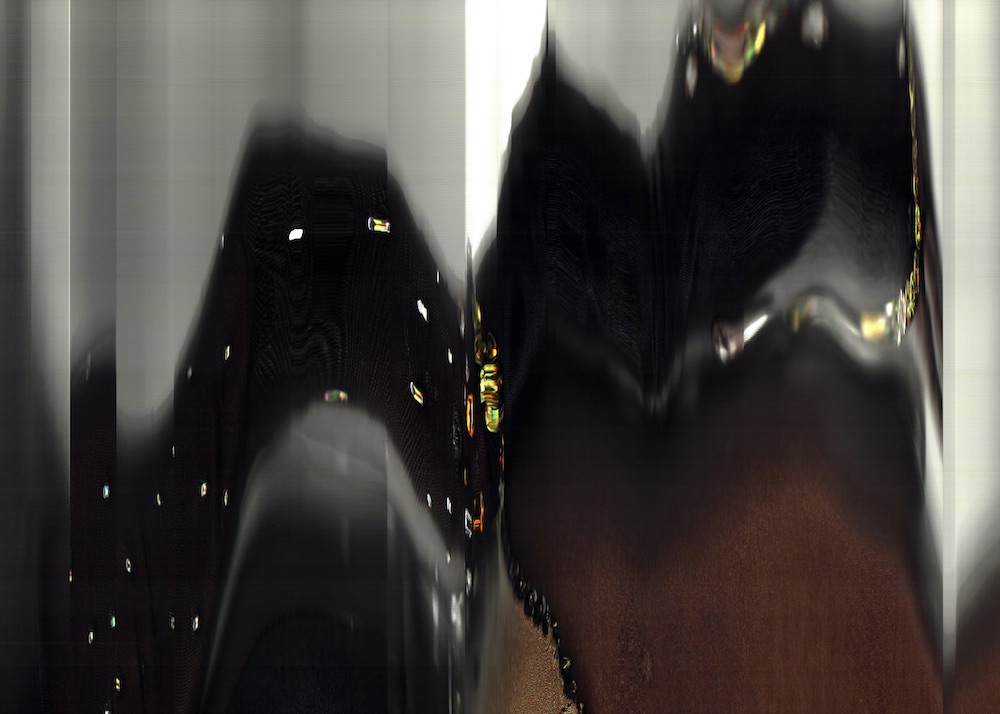

I hoped to embrace the increasing diversity in the sport, and to question how this might impact the aesthetic representation of gymnastics. In the spirit of favela living I repurposed a cheap scanning wand to interact directly with the moving gymnastic bodies in the open training arena. Working in the sharp contrast of the Rio sunshine and the shaded areas of the training hall, I developed a huge archive of body scans, working in close collaboration with the young girls, who selected elaborate performance leotards, handmade by their mothers and grandmothers, for each portrait.

How do your Brazilian images compare with your other projects dealing with gymnasts?

These new images are a total departure from what has come before. They are bold, colourful, wobbly and, in many cases, abstract. They are intended to be used in various ways: as large-scale paper sculptural pieces, as flags for performance interventions, and also as the already-produced New Order (Brazil)—a cluster of shimmery, dye-sublimation prints made direct to aluminium. The images document the lived reality of training in difficult social and political conditions. During the making of this work the club was suffering fallout from the corruption case being brought against their sponsor, the disgraced state energy company Petrobras: the gymnasts still training in their corporate colours, despite coaches working unpaid and facilities unfunded. The images detail hot bodies and dirty outfits: open pores, unshaven legs, darned seams, stray sequins, but somehow still appear vibrant and energetic, embodying the vitality and passion of the young girls.

And your projects on prize whippets?

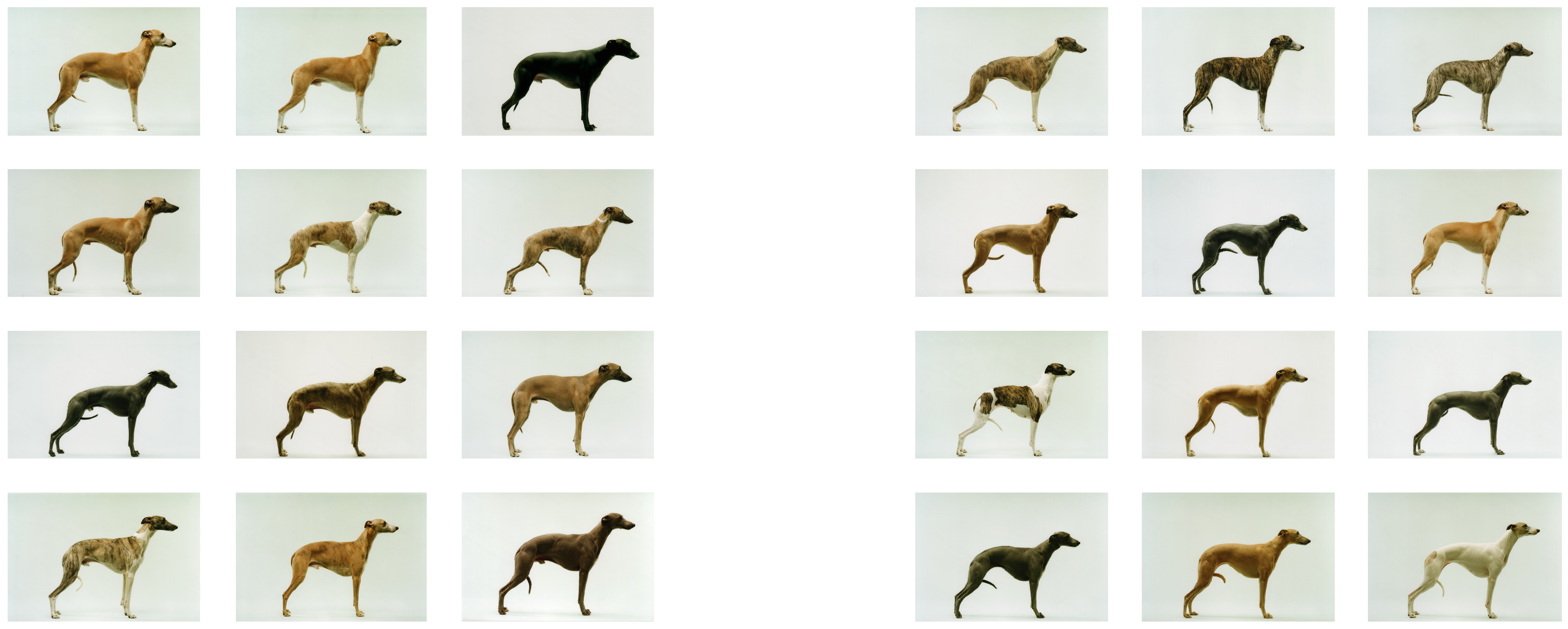

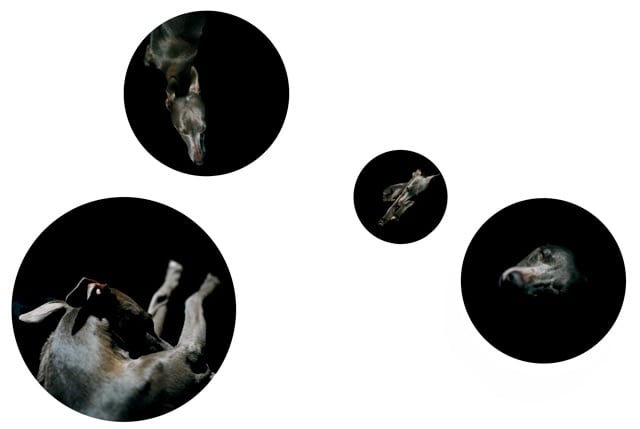

Of course, the dogs came before the gymnasts, and provided a touchstone for all the future works. At the outset of The Refusal I wanted to explore the idea that one might breed a “perfect” dog, as described by the Kennel Club of Great Britain in their Whippet Breed Standard. Although, technically, a dog’s temperament is also taken into consideration, I focused, like the breeders, on ideal body form and how traditionally such a thing would be represented. Both projects also question received ideas of the perfect photograph—how one might best photograph a champion whippet; how a professional sports photographer might most successfully capture those elite performances—and both projects reveal a surprising conformity in the images produced by professionals over many decades. In each case I worked from an initial multi-part study (Twelve Dogs, Twelve Bitches, A–Z), which revealed to me the uncharted territory, the more interesting grey areas to explore in my subsequent works.

“Historical aspirations towards perfection seemed inextricably linked to social control and various aspects of fascism”

It is conventional to contrast the flawless and the flawed, perfection and imperfection. However, would it be true to say that your ongoing interest is slightly different: perfection not as state of being, but as an ongoing process, or a destination that is aimed for but never reached?

That’s a fair description. I’m not much interested in perfection itself—I’m not even sure it exists. Maybe we experience a perfect moment every now and then (Lou Reed certainly did…) but it’s always fleeting. I’m more interested in the many cultural notions of perfection—and the often fluid and fluctuating propositions these entail—as well as the human obsession and drive that underpin attempts to achieve them.

In what ways do your photographic style or styles complement your subject matter?

I guess my personal obsession is with immaculate production values, and control of the quality of the final object and/or installation. For me, my work is not just a disembodied online image or a photograph, which might be hung in any old frame. I would like to think my actual style is open and diverse, reflecting the needs of the project in hand. I certainly have an aversion to traditional ideas of a perfect photograph, which tend to foreground composition, focus and technique over affect. I use film cameras of various formats, as well as digital SLRs and other more recent technologies, but not everything has to be high tech. I’m equally at home using old stereoscopic projectors, or producing works as laser copies, vinyl or fabric banners—just so long as they are installed to my precise requirements!

You organized an ambitious symposium on the theme of perfection at London’s Whitechapel Gallery that was subsequently made into a book, published by Intellect. What did you learn about perfection from these two initiatives?

We all agreed that perfection is a hard act to pull off, as most eloquently described in Francette Pacteau’s examination of Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House—a house praised for its formal perfection, but which suffered many indignities as time passed in an ongoing struggle with man and nature. It did not come as a surprise to me that most artists in this project were not overly interested in perfection itself, with the notable exception of Leni Reifenstahl, whose obsessional attention to every detail, and constant editing and re-editing of her works, were foregrounded in the illuminating discussion with director Ray Müller on the making of his film The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl. Julian Rosefeldt jokingly admitted to perfectionist tendencies, which were quite apparent in his stunningly produced film installation Trilogy of Failure, but then humorously undermined by the absurdities played out by the protagonist of Part III, The Perfectionist

.

We fairly unanimously agreed that perfection is a sterile concept, and often the enemy of creativity. Artists more often embrace chance happenings, or that slight imperfection that can make something all the more compelling. On the dark side, historical aspirations towards perfection seemed inextricably linked to social control and various aspects of fascism, and marked a well-trodden path to disaster. I am often accused of being a perfectionist myself, which I find quite laughable. In my defence, I would say that I have to aim high to achieve the “good enough” result that most of us are happy to settle for.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 32

BUY NOW