Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

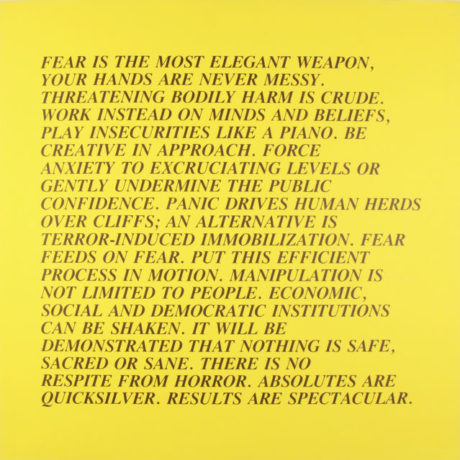

Out today on Artsy is Ally Faughnan on Jenny Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays.

The Hackney Flashers

grabbed me instantly. Working in the Hayward Gallery archive, I came across the feminist collective in the catalogue for Three Perspectives on Photography (1979). In the 1970s and 80s there had been a mania among dirty old men for exposing themselves in public. It rendered crossing the local park, for example, a gross kind of cat and mouse game, trying to spot lurkers and judging whether one was likely to flash you. In 1974, the Hackney Flashers would have been a feisty moniker for a group of women working with photography. Fierce, funny, feminist: it was an irresistibly in-yer-face combination.

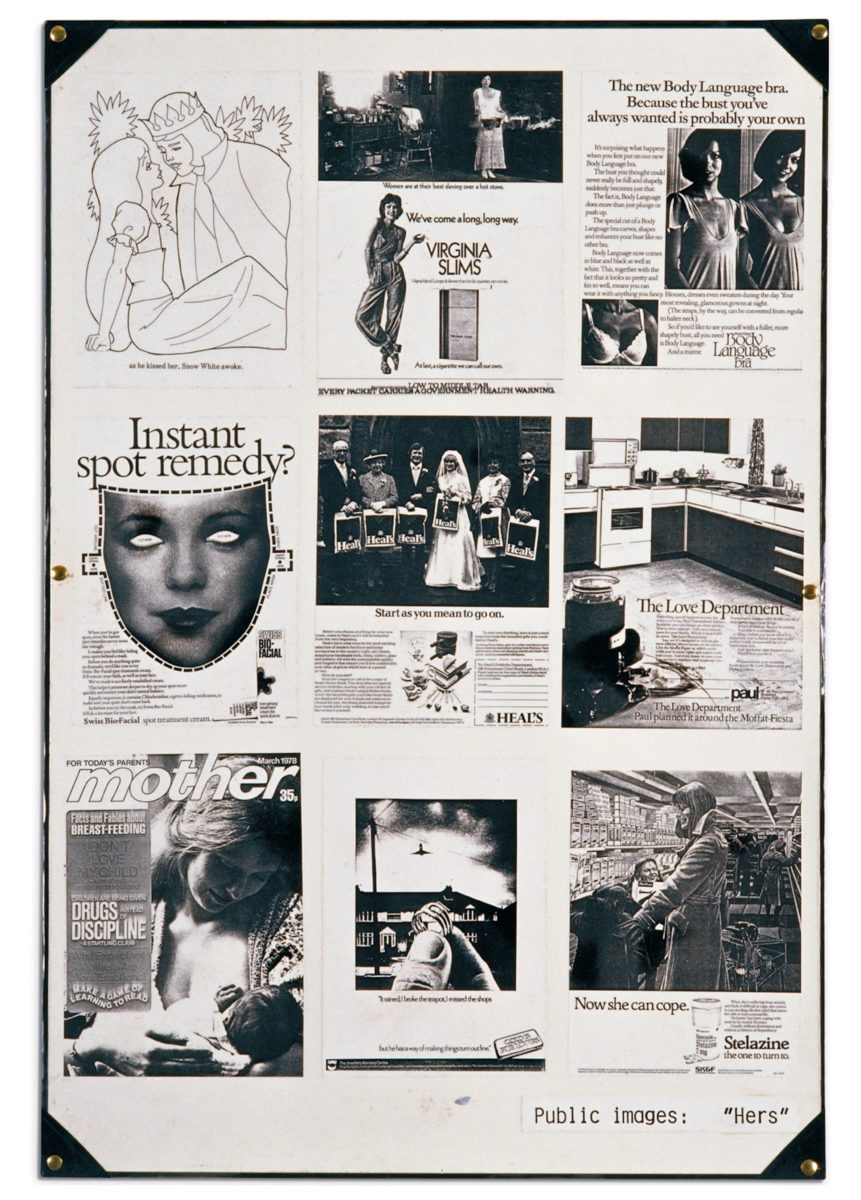

Instigated by politicized photographers Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, eighteen members participated in the Hackney Flashers over the years. Most were women. Based in a working class district of North London, then ravaged by unemployment and poverty, they turned to documentary and photomontage to raise questions about how women were seen and treated.

Low pay and the invisible domestic grind—pressures faced both in the day-to-day and in relation to the feminine ideal promoted in the mass media—were tackled with a mordant wit. In the Hackney Flashers’ hands, a repurposed cosmetics ad of a Lurex-clad vixen on a velvet sofa read: “You’ve tucked the kids into bed… slipped into something simple… taken your Valium… And you’re waiting for him to come home… mustn’t be late for the evening shift at the bread factory.”

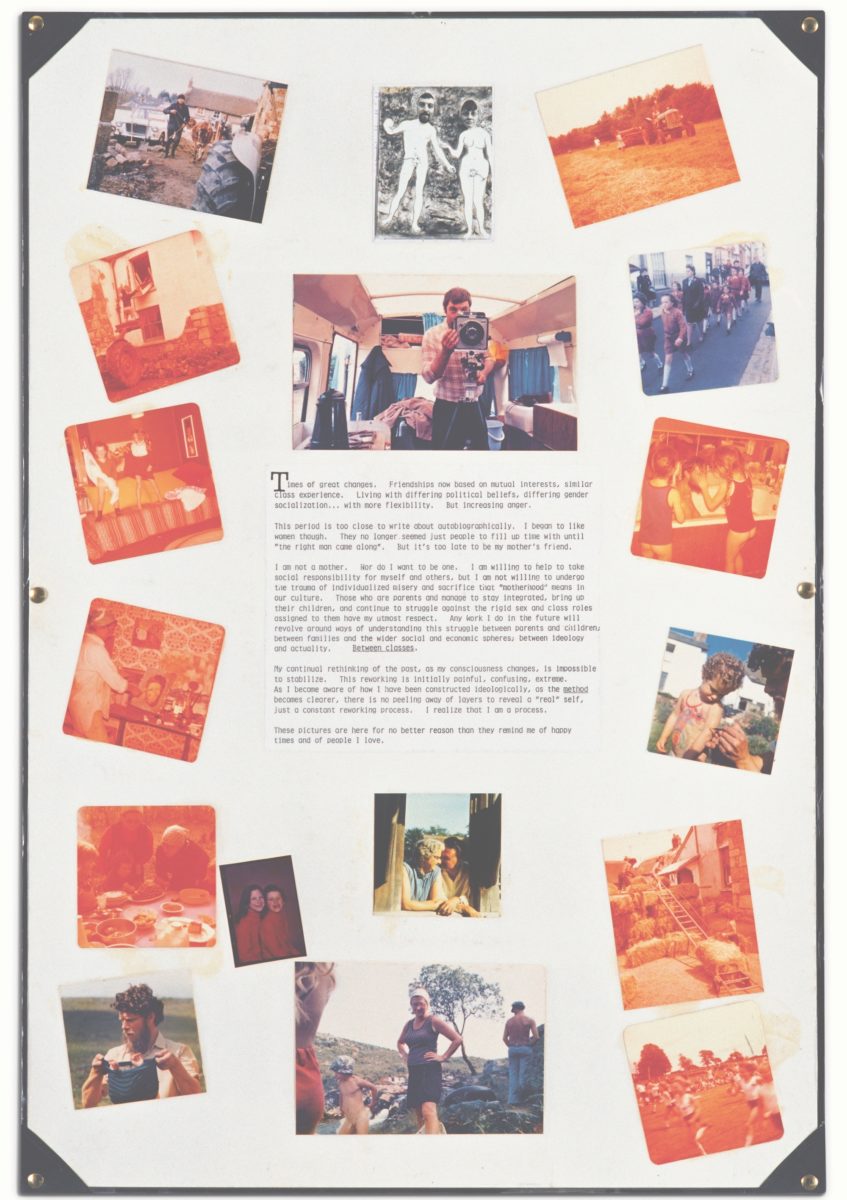

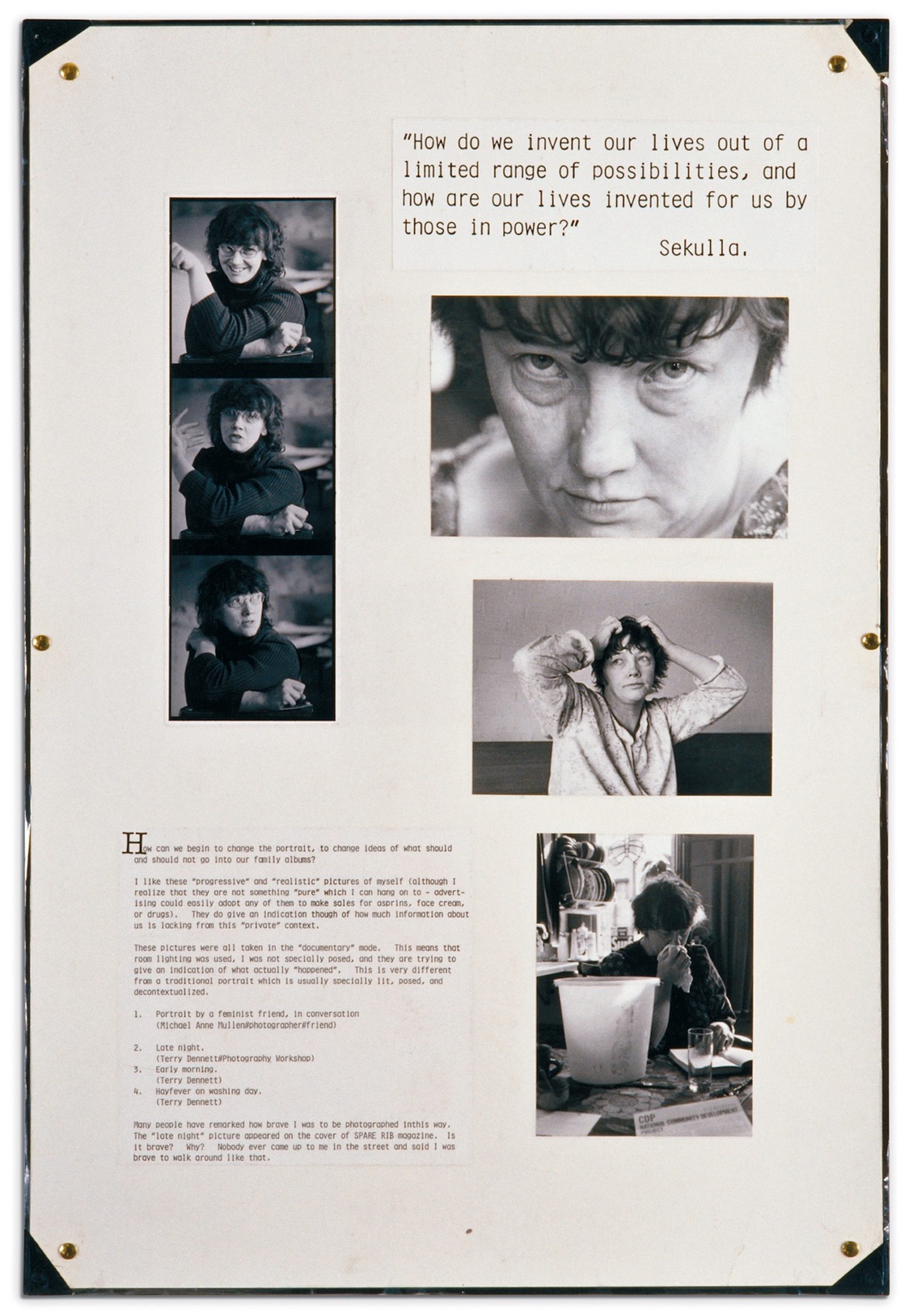

Spence also showed under her own name in Three Perspectives on Photography. It was the first time she had been commissioned to make work for a gallery—she later described the experience of exhibiting at Hayward as “totally alienating”—but the result was a remarkable project exploring family, class, womanhood, the role of the camera and the performance of editing. Spence had already moved from studio photography to documentary. In Beyond The Family Album (1979) she turned her gaze on herself.

“It was the start of a lifelong project exploring issues of the self, class, society, womanhood and representation”

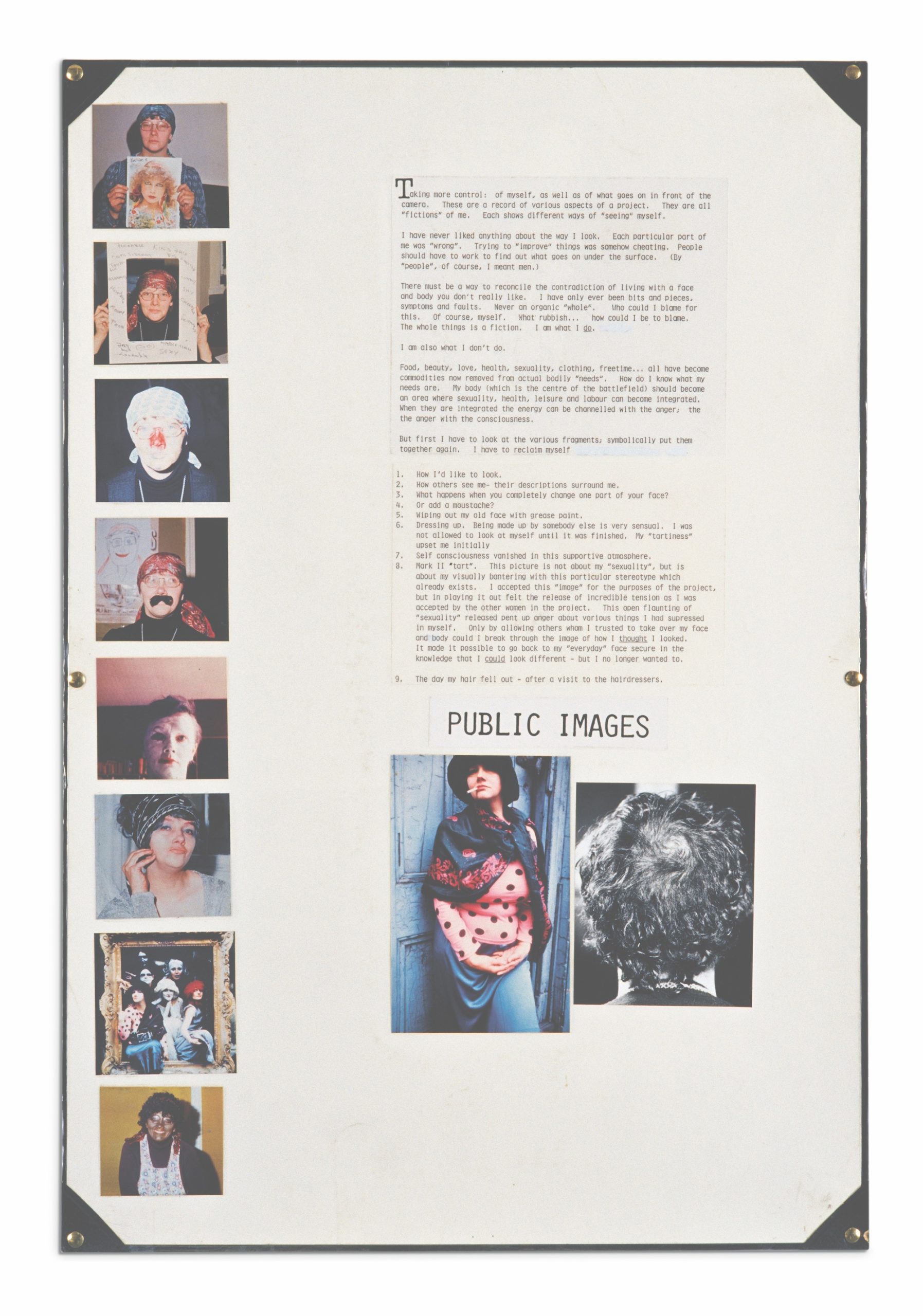

What Spence showed was not, for the most part, her own photographic work, but instead her life as seen through other lenses: those of dad, granddad, school photographer, boyfriends various and professional colleagues. In the extensive text, she fills in details of what we are not shown: her parents’ working lives; her misery and ill health as a wartime evacuee; the deterioration of relationships. Having spent years watching sitters perform for her camera in her high street studio, she analyses the way she, too, learnt to compose herself for the lens as a young woman. “Offering myself to the camera with a variation of ‘The Look’” she captions one photo. Another: “Twenty-nine years: a last fling at being ‘beautiful’.”

At the end of the display, she presents a contemporary self-portrait—life-sized composite, grinning—an attempt at an honest, comfortable relationship with the camera. It was the start of a lifelong project exploring issues of the self, class, society, womanhood and representation that would ultimately take Spence through breast cancer, therapy and leukaemia.

I think about Spence often. About how she examined the conventions of photography within the domestic sphere: what we choose to show, and what we choose to conceal. Looking at her childhood self through a lens, she encourages us to detect the complicity between sitter and snapper, and the way they conspired in the moment to compose a “good” image. (In a later project she would recreate these sessions as phototherapy, getting back in touch with her child self.) Seeing photographs of her youth and young womanhood, she identifies a sense-memory of the internalized critic dictating that one must be beautiful, sexy and available for the camera. Later there are different imperatives: to be serious and professional, clever or approachable.

No image is complete, or completely satisfying, because introducing a camera into a scene affects more than our memory of it. It alters the moment itself, shifting focus, introducing a new level of self-awareness and the instinct to conform to accepted modes of self presentation. (Spence had observed this earlier on, attempting to photograph young children engaged in private play: once her presence was registered, the play was no longer private but performed.)

I often wonder what she would make of our current image era: the embrace of conformity for the camera; the infants growing up with the omnipresent surveilling lens of the parental smartphone; the ever more ruthless editing of our imaged lives.

Since first seeing her work I have reached and passed the age Spence was when she travelled Beyond The Family Album. Increasingly I glimpse her body in my body, her face in my face. It interests me that we still use terms like “brave” when describing her self-portraits exhausted, hurt, singed, naked in the landscape, or topless on the front step above the milk bottles. The ageing body remains taboo. In sexual terms, a middle-aged woman with a visibly ageing body has shifted from the realm of romance into that of farce.

Recently I started wearing glasses again (earlier, laser surgery had put a temporary end to a bespectacled “speccy” childhood.) When I first undressed with my new frames on, I thought of Spence’s observation that “nudes never wear glasses,” and felt that I should defiantly perform as nude rather than merely naked.

“In sexual terms, a middle-aged woman with a visibly ageing body has shifted from the realm of romance into that of farce”

When Spence was the age I am now, she documented her body before, during and after a partial mastectomy for breast-cancer. “Brave” again, we would say. A decade later, following the horror of leukaemia, she took her final self-portraits on her deathbed. I choked when I saw them. Even thinking about her face in those pictures has my eyes filling with tears, as though remembering the death of a beloved friend.

That word “brave” marks how hard it remains, decades on, to step past learnt conventions of domestic photography, to go definitively beyond the family album and to document ourselves discomposed, unbeautiful, hurt, ageing, unhappy, ill and inconveniently sexual. Spence’s determined transgression brought its own kind of appeal: something irresistible that no contrived pout for the camera could come near.

In truth, she and I have little in common beyond gender and city of residence. My feeling of closeness comes not from kindred experience but Spence’s deep sharing of self. In her hyperawareness of the camera lens, she miraculously leaps past it to offer images that are vulnerable, complex, direct and disconcertingly close to honest.

All images: Jo Spence, Beyond the Family Album, 1978-1979. Courtesy MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. Work acquired thanks to Terry Dennett. © Jo Spence Memorial Archive London. Photographer: Rory Moore

Did an artwork change your life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to office@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life.”

Head to Artsy to read their latest story in the series, a piece on Jenny Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays

READ NOW