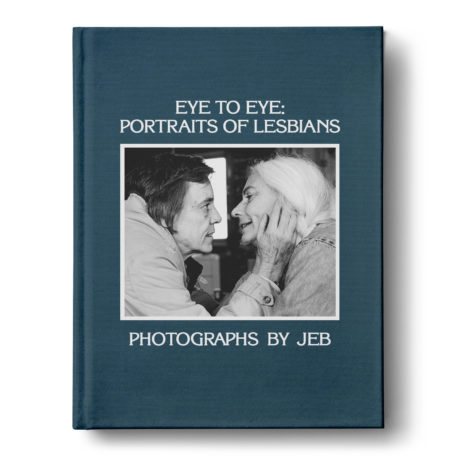

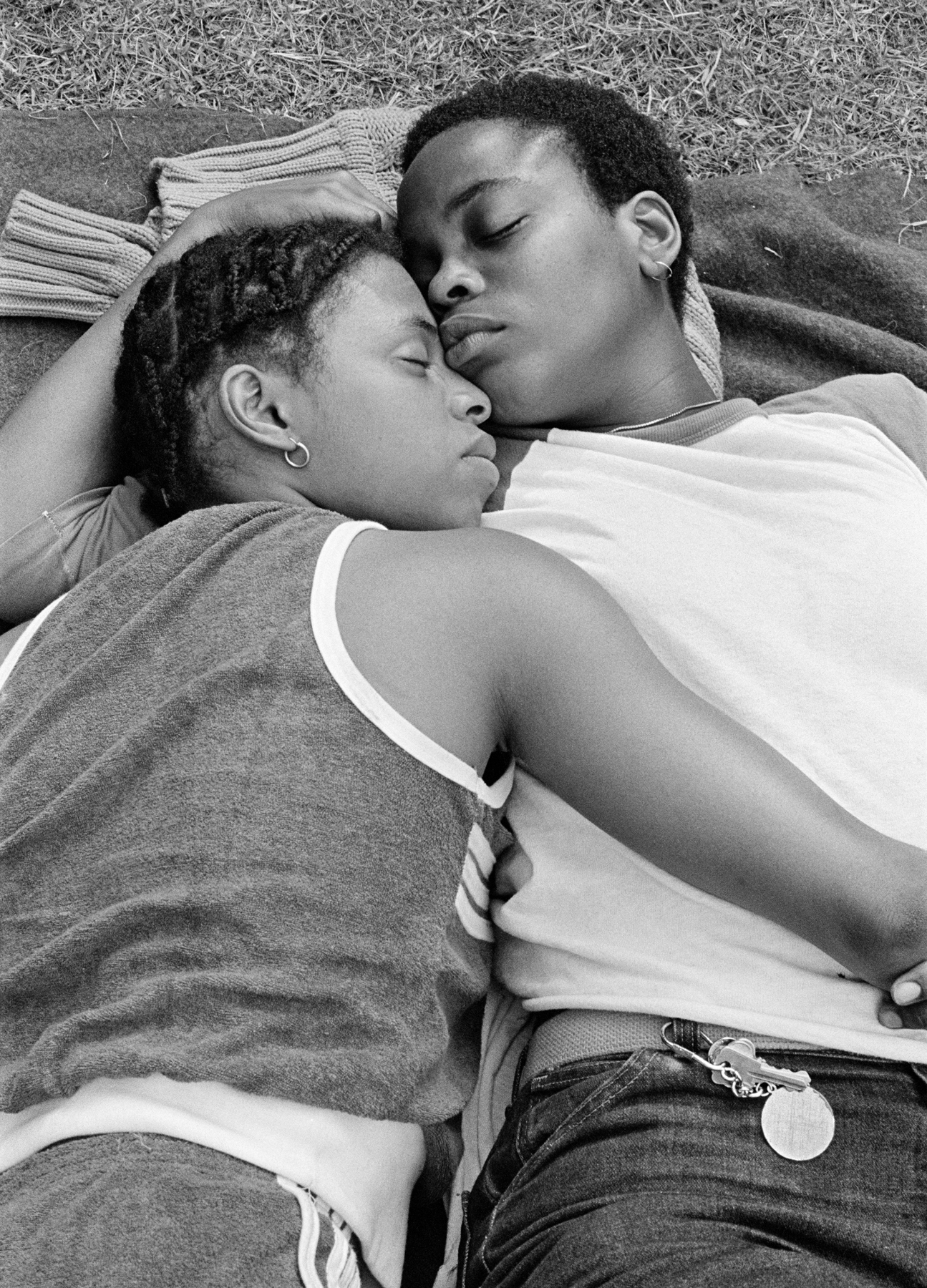

“The women in these portraits were some of the first dykes I ever laid eyes on, and the book felt like a long-lost family album.” This moving quote by Alison Bechdel, the American graphic novelist, describes her encounter with Joan E Biren’s (known as JEB) landmark photobook Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians. Originally self-published in 1979 and now reissued by Anthology Editions, the book chronicles intimate photographs of lesbians in their everyday lives: working, mothering, protesting, playing sports, at leisure and in love. The book speaks to lesbian identity as an intersectional ecosystem, thereby heralding a radical new way of seeing.

Now in her 70s, Biren saw the camera as a revolutionary tool. She began to document the lives of LGBTQ+ people in 1971 as part of her lifelong dedication to social justice. Her ethos was “you can’t build a movement without visibility”, but it demanded the participation of other women; those who agreed to be photographed were a courageous minority. At that time, the consequences of being out could be devastating: being identified as a lesbian put you at risk of losing your children (a reality for many—including one of Biren’s lovers). You could be fired from your job, disowned by your family, expelled from your place of worship, thrown out of your apartment or deported (even if you had a visa). These acts of violence were both common and legal, placing the community in an unrelenting cycle of fear.

“The album captures the tenderness between women loving women, memorialising lesbian life and creating space to come home to ourselves”

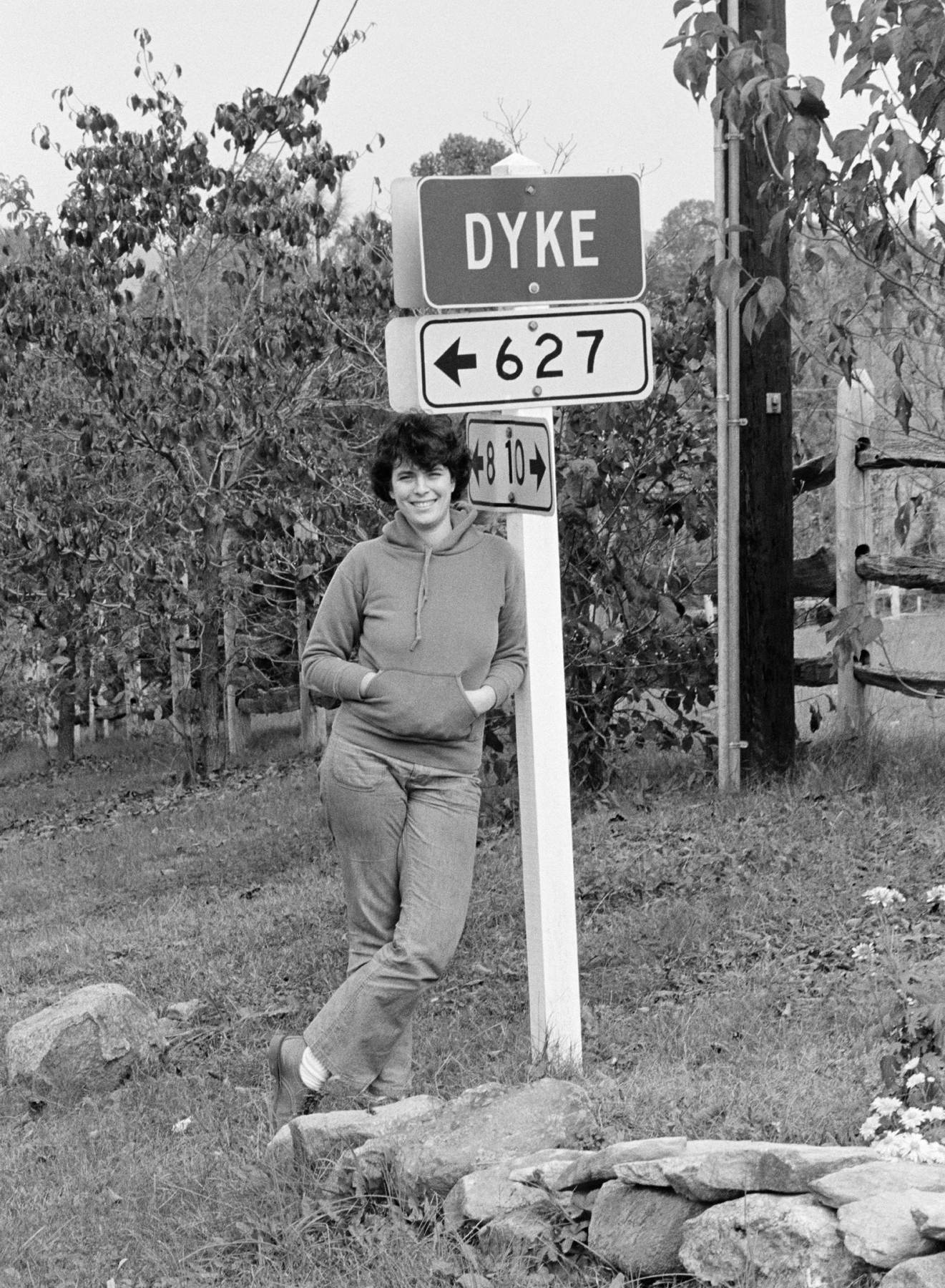

Joan E Biren self-portrait, Dyke, Virginia, 1975. Courtesy JEB (Joan E. Biren) and Anthology Editions

Biren’s relationship to photography was not just political; it was personal. Her first image, made with a borrowed camera, was a selfie with her lover Sharon Deevey that immortalises them kissing—a revelatory moment for Biren who never saw herself reflected in the imagery of the time. She began to think of her camera as a barometer for the movement, measuring progress via the numbers of people willing to collaborate in front of it. The resulting images became a conduit for talking about being seen in public for who they were, reminding lesbians who felt isolated that they were not alone.

I grew up queer in the 1990s, some four decades after JEB. The dominant representations of lesbians I encountered were confined to prison dramas, faux imitations in rap videos or deviant man-hating vampires in horror movies. Jamie Babbit’s But I’m a Cheerleader (1999), the story of a high school cheerleader whose parents send her away to a conversion therapy camp to cure her lesbianism, was a strange but potent affirmation. While the context was a tragic reality for many young queer people coming of age in religious communities, the film was radical for the simple fact that it concludes with love and joy (still rare in cinema today).

Just consider Hollywood’s current obsession with confining lesbians to history or movies like Happiest Season (2020), touted as a milestone in lesbian representation but more accurately described by Rosanna Mclaughlin as “a harrowing tale of assimilation”. While progress is undeniable, much of the heavy lifting has been undertaken by the community itself, using social media as a site to expand the boundaries of identity and self-representation.

This lack of equity in culture is just a symptom of the institutionalised homophobia still rife in daily life. My wife and I lived in East London—an area that prides itself on progressive values—for a decade, yet it was not uncommon for us to be affronted by religious fanatics or spat on walking down the street. In an emotional visit to the emergency room with our then six-month-old baby, we were repeatedly asked by the young male doctor, “but which one is the mother?”

“What I love most about the book is that it offers an opportunity for queer elders to engage in a vibrant, multigenerational conversation”

Friends and colleagues are often shocked by these experiences, which remains a frustrating confrontation with the perception that homophobia is a problem of the past, or happening elsewhere. While my experiences can be tabulated as microaggressions, we still live in a world where violence, curative rape and death are very real threats for queer people. Seventy-two countries still criminalise LGBTQ+ people, and same-sex unions are only legal in 29 countries. The fight for freedom persists. As Biren’s friend, collaborator and contributor to Eye to Eye, Audre Lorde famously said, “revolution is not a one-time event”.

When I look at Biren’s photographs, I am most struck by what I don’t see: the profound risk these women undertook to be photographed in the first place. The ways they found to survive and thrive when safety was an issue every day. Biren herself shouldered great responsibility to author the work and protect the community that entrusted her. Their fortitude to unite through picture-making is a generous gift for our collective queer inheritance.

Bechdel’s quote, which adorns a small sticker on the new edition of Eye to Eye, is a sentiment that I share. This communal chosen family album captures the tenderness between women loving women, memorialising lesbian life and creating space to come home to ourselves. It illustrates a community manifesting; visual evidence validating lesbian existence as they tried to figure out a path forward. Biren’s primary intention was to drive social change, but she inadvertently preserved an expansive record of lesbian life, complete with gestures and style that traverse the gamut of gender. What I love most about the book is that it offers an opportunity for queer elders to engage in a vibrant, multigenerational conversation rooted in strength and empowerment.

“Acts of violence were both common and legal, placing the lesbian community in an unrelenting cycle of fear”

Forty years since the original was published, Eye to Eye reanimates photography’s vast potential. It’s a generative tool, full of force, which serves to raise consciousness as a form of liberation. “[Biren] ensures that each of us can not only find ourselves in the work but also enjoy a comprehensive pride that is often otherwise denied,” photographer Lola Flash writes in this new reissue. The images, she concludes, “have as much impact and importance today as they did when the book was first published”.

All images from JEB (Joan E Biren), Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians. Courtesy Anthology Editions

Joan E Biren, Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians

Published by Anthology Editions, March 2021

VISIT WEBSITE