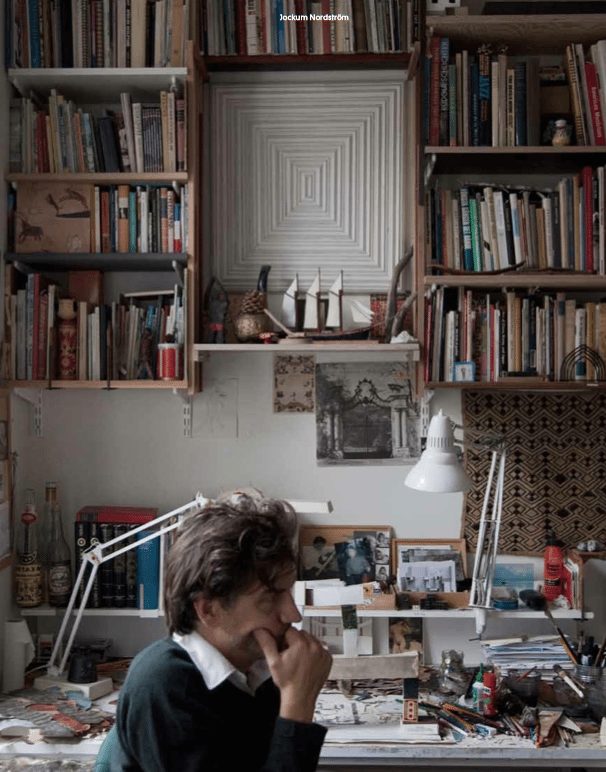

After a brief tour, Jockum Nordström invites me and my brother Alexei into his workspace — a library just off the living room, crowded with books and magazines. Instead of images, many of their pages hold absences: cavities and cut outs, the signs of Nordström’s interventions. On the floor and desk are stacks of shapes and outlines, scraps and papers, more books, vinyl records, an electric guitar off to the side. Pinned above the desk are photographs and drawings. Paintbrushes and glue sticks are within easy reach; sprays, pastes and, of course, scissors. A tape dispenser, coloured pencils and matchboxes stacked one on top of the other. Along the walls are some of the three-dimensional cardboard buildings that Nordström hasn’t shown anywhere, yet. This is only a fraction of the size of his old studio in the suburbs, Nordström says. He and Andersson have just relocated to the city. He’s still getting used to it. I’m used to it already, I say (maybe without thinking). I feel like opening every book on the shelf to see what’s missing in it. To me, this studio is like a Nordström collage, arranged with the most sensitive eye for accident and unruffled commotion. A rainbow of muted colours, to complement the backdrop of a muted day. We’ve only been awake for something like four hours, and already it’s getting dark outside.

After a brief tour, Jockum Nordström invites me and my brother Alexei into his workspace — a library just off the living room, crowded with books and magazines. Instead of images, many of their pages hold absences: cavities and cut outs, the signs of Nordström’s interventions. On the floor and desk are stacks of shapes and outlines, scraps and papers, more books, vinyl records, an electric guitar off to the side. Pinned above the desk are photographs and drawings. Paintbrushes and glue sticks are within easy reach; sprays, pastes and, of course, scissors. A tape dispenser, coloured pencils and matchboxes stacked one on top of the other. Along the walls are some of the three-dimensional cardboard buildings that Nordström hasn’t shown anywhere, yet. This is only a fraction of the size of his old studio in the suburbs, Nordström says. He and Andersson have just relocated to the city. He’s still getting used to it. I’m used to it already, I say (maybe without thinking). I feel like opening every book on the shelf to see what’s missing in it. To me, this studio is like a Nordström collage, arranged with the most sensitive eye for accident and unruffled commotion. A rainbow of muted colours, to complement the backdrop of a muted day. We’ve only been awake for something like four hours, and already it’s getting dark outside.

We’re on the cusp of deep winter in Stockholm. No matter. As far as I’m concerned, short days make for more hours of flattering lighting. And in this early twilight, the city park outside moves with the jolly melancholy of an ‘I miss you’ card. I notice a small turtle watching us. ‘He can be shy’, says Nordström of his pet. Somehow the absence of a turtle would have been more surprising.

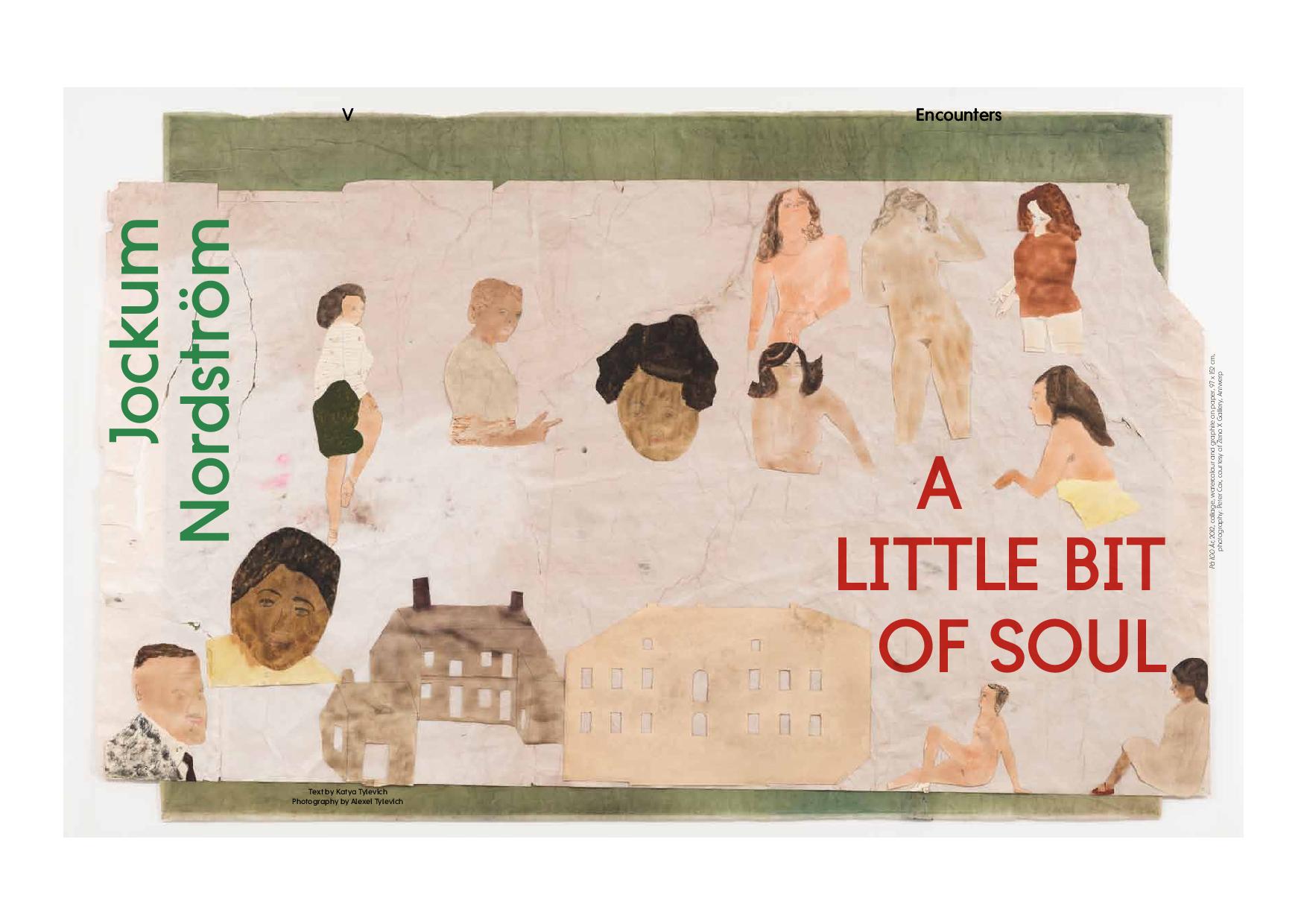

Looking at Nordström’s works, I’ve often felt the pleasure of an enormous peeping Tom, a noisy giant who’s opened a matchbox to find an intricate, distorted world inside to spy on. More than once I’ve laughed aloud at the expression of a character’s face in one of Nordström’s drawings, or at the entrance of an uninvited body part into a larger scene, or at a startlingly good title (such as Take Great Care Not to be Rash, 2000)— and then I’ve wondered if I should be laughing, really. Where did that come from? I hope nobody heard. The ambiguity of it is both unsettling and delightful. Meanwhile, Nordström is telling us about the time they had to take their turtle to the veterinarian. I lock eyes with the reptile to express my sympathies and, just as surely, the reptile turns away.

I could spend all day looking at the books in your studio.

I love to read, but I like to do it slowly. I prefer poems to prose.

Does that have something to do with how poems are structured, visually?

I think so. Somehow it isn’t as clear where a poem stops and ends. It’s the same with art. I used to love movies when I was younger, and I took away many important moments from them, but today it bothers me the way movies stop at the end. A to B, then darkness, and that’s it. Really, I want a feeling more than I want a story. Sometimes the feeling and the story are the same thing, and I can stand that. That’s good. But the older I get, the harder it is for me to take something with a beginning and an end. Music is easier on me. So is art.

Aren’t you a musician?

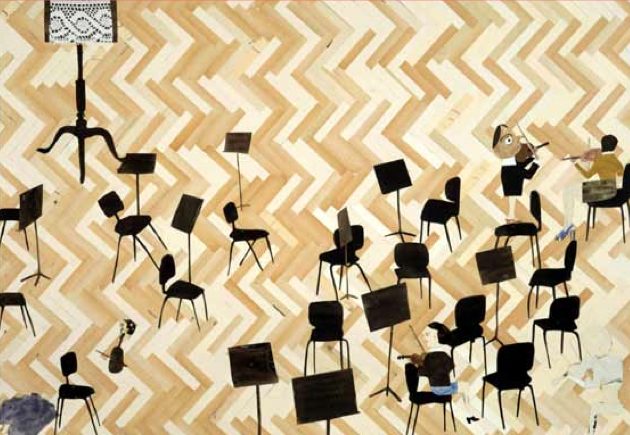

I play a lot. I’m making a record now with a friend. But, really, he’s the musician, not me. I made the covers. [Laughs.] I played a lot of jazz when I was younger. I play bass and guitar. Sometimes, on this record, I play drums. Do you want to hear something? [Pops the CD into the stereo; it has a jazzy sound, improvisational.] I’m not very good. [Laughs.] Unlike my friend, I don’t have any education in music.

Do you ever write your music down in notes?

Never. But I don’t have to be precise. And we can never play live either, because the two of us play all of the instruments.

Do you have a label?

I don’t think we’re going to go with a label, although we’ve had offers. Some people in big record companies like my work and are interested, but my musician friend says that we must do it ourselves.

Is music a distraction from your art?

Yes, and it’s been very good for me to have that feeling of playing hooky form school. I don’t feel pressure when I make music. It’s really very playful. It’s also good for me to collaborate with others; otherwise I’m so alone when I work. Art is a very private thing for me. I have another studio, walking distance from here. It’s good, when I need to close the door on the dog. [Laughs.] This room we’re in is good to work in alone, for maybe six hours a day. But sometimes I want two months where I don’t have to move a single thing in the room.

Do you feel different working in the city, since you’ve moved from the suburbs?

I think it was better for me in the suburbs. The difference in the city is that a lot of artists live and work around here too, and we all know that we’re artists, so when we leave our studios and run into each other, we talk about work. In the suburbs, where I lived, the neighbours knew each other, but we all did different things. When we ran into each other outside, we could just say, ‘Hello. How are you? Fine’, and keep going without having to talk about work.

Is it difficult for you to talk about your work?

Yes, especially if it’s in progress. It becomes easier if a project is near its end.

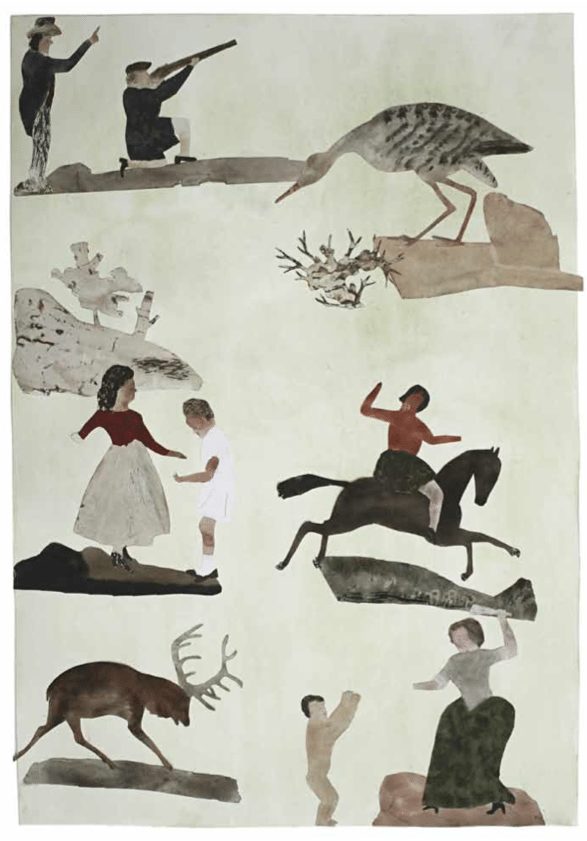

Do you work from a plan? When you put together a collage, for example, do you already know where your cut outs are going, or is it an improvisation, like your music?

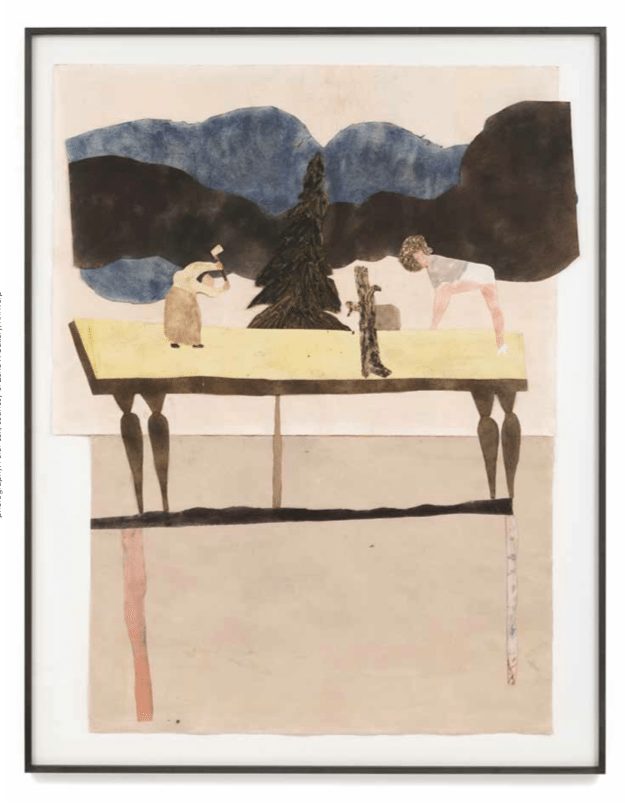

When I was younger, I began with ideas. I knew the compositions that I wanted to make, either in terms of the colours or the feelings that I wanted to portray. But for the past seven years or so, I’ve been more free. I don’t like working towards a solution anymore, because then the work is stiff from the beginning. Now it takes me a while to see what I’m doing and what I’ve done. Who knows, maybe in five months I will have a different approach, but that’s how I feel now. Sometimes I work for half a year just to finish two pictures.

In that case, are your works impulsive — in terms of the subject and the medium?

If I see a book I like, I buy it. [Pulls a book off his shelf.] This is a book from 1903 about fish, birds, crayfish and jellyfish. I like the book, I want to do something with it, but it’s not my Bible, it’s just one street I’m walking down. After I finish walking down this street, I go down another. When I’m tired of walking the same streets, I play music, or do something else. When I play music, I really want to make art again. Right now I’m working with collage, but I’m longing to make drawings. Compared to collage, for me, drawing with a pen is more private and very close.

Also, with time, your interests and your focus change. When you have a dog, you see dogs everywhere. I remember, when I was younger, I went through a period when it was very important for me to draw hands. In every painting I looked at, I saw a hand. I tried to look at it another way, and I saw the hand anyway. Somebody would say to me ‘Hey, what are you looking at? That’s a bad painting.’ But it didn’t matter to me. I saw the hands, and they were good. It can be that way with the ideas that come to you: you don’t have to love the picture you’re looking at, but it can inspire you anyway.

Do you think your works are related to each other?

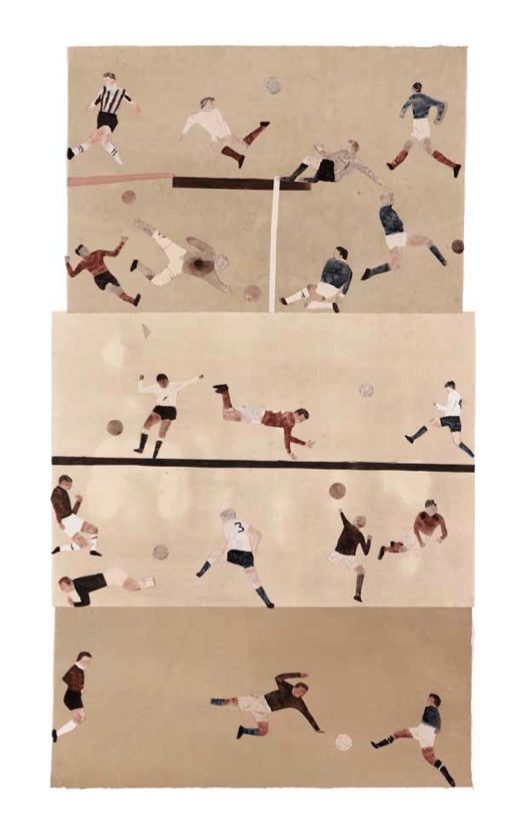

I think of them like a chain. I could never do this work if I hadn’t done that one before it. Even when I make a new work because I’m fed up with an old one, it’s the old work that led to feeling fed up.

Have you felt that you were an artist from a young age?

Yes, I have been drawing since I was very young. I have two brothers: one brother is two years older than me, and we always drew together. When he became a teenager he stopped drawing, but I couldn’t. I drew all the time. Even when I felt I wasn’t creating good work, I had to do it. It was as important as eating to me. My eyes were much better when I was younger. I could work for 16 hours straight, sometimes 20. Now I have to wear glasses. 20 minutes and my eyes get tired. It’s so unhealthy for the eyes, what I do. When I go to bed sometimes, I turn off the light and I see grey in one eye. I make more cut outs today, partly because of my health.

People forget how physical art is.

My knees are also very bad. I have been operated on seven times now, I think. I always used to work on the floor—that was my space, where I cut and painted. But with bad knees, you lose your tempo; you can’t work the way that you want to.

So the body persuades you to work in a different way.

I think so. I think my work has changed because I’ve had to change the way I work. I’m old. I’m 48 now. I see examples in history of other artists who have had problems. I see how they changed. Matisse, for example, you know, he was making cut outs in the end. [Laughs.] He was pointing with his long brush, and telling another guy to go up the ladder. A lot of people ask me if I’m going to get an assistant, but I can’t. The process is too private for me. I want to have time — sometimes a long, long time — where I can just read and listen, and maybe draw very slowly.

I don’t want to be disturbed. If you work with other people, they come in at five o’clock and get the coffee going. I don’t want that. It’s very important for me to be alone a lot. I do like to work with people sometimes. Like in the beginning, I worked a lot for newspapers, creating illustrations. It’s good for some years of your life, but, in the end, it’s boring. You do the same thing all the time.

It sounds like you can’t do the same thing for too long.

No. Then your life becomes like dripping water: drip, drip, drip [he imitates]. It’s torture.

Do you always complete the work you start, or do you sometimes leave work unfinished?

I think you’re in good shape when you have a lot of things unfinished. That way, there’s always room to go on with your work, somewhere to take off from. Still, I can’t leave a project before it has a little bit of a soul. It must have soul before I leave it alone.