What happens when we pervert our understanding of nature?

If we embrace a queer nature and ecology we can uncover the myriad, exquisite forms of sex and relationships on Earth. We obsess over what life is like on other planets, but the insane world right beneath our noses remains alien and unrecognized. The penises of male honeybees snap off and explode during sex; the female praying mantis eats the head of its male partner…

How do you explore this darker underbelly of sex and reproduction in non-human relationships in your practice?

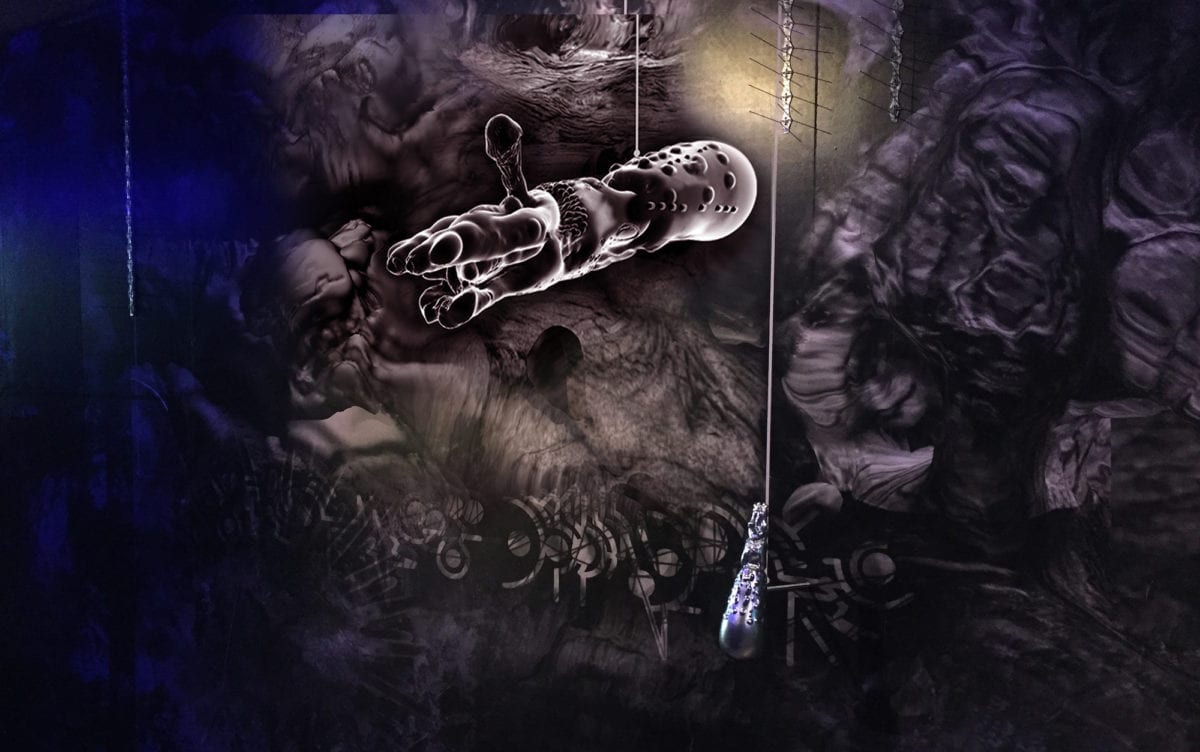

The Evolution of the Spermalege (2014), which I recently exhibited in the Robot Love expo in Eindhoven along with sixty other artists, surveys the sexual anatomy and processes of various insects—in particular, the penis of the Callosobruchus analis (bean weevil) insect. The male basically penetrates the female on any part of her body so that the sperm goes directly into her blood stream. This is obviously a high-risk form of non-consensual sex, and often the female dies. But I believe that looking at alien mating practices such as this can disrupt the way that we conceive of our own biological capabilities and our own bodies.

- Joey Holder, The Evolution of the Spermalege, Ongoing project 2014-2019. Courtesy of the artist

How did this project take shape at Robot Love?

It was located in this long, dark corridor—which is perfect, in thinking about the installation as a sort of cave or womb. Thanks to the Niet Normaal Foundation, the organization behind the expo, I was able to cast silicone insect genitalia out of the 3D models so they can be used as sex toys. This iteration of the project morphs our sexual pleasure with the pain of other species; it’s an intimate and complex relationship that also reflects a more perverse truth about human sexuality. Through sex we take on our partners genetic material—and I don’t just mean with the conception and development of a fetus, but how our bodies are affected and imprinted by the sex organs of another human, on a hormonal level very much hidden from our conscious understanding.

What about the relationship between biology and technology?

By thinking about biological processes as a piece of technology, it can paradoxically bring us closer to nature, as technology is an immediate extension of ourselves. It is hardly a stretch to think about machine learning and even the Internet as biological processes. Both involve the construction of an artificial system that filters and classifies content based on a hierarchy. We think that categorization is an inherently cultural thing, but by reducing the complexity of the world we end up alienating ourselves from strange and wonderful parts of nature.

And these categories all filter the world through human ideas of linear progress, production and consumption…

Exactly. One of the texts that influenced my thinking very early on was The Savage Mind by Claude Lévi-Strauss—although the author uses the terms “primitive” and “savage”, which isn’t great today. Anyway, he surveys how Native American tribes categorize the world through a non-hierarchical, interconnected perspective. Things are related not in a pyramid scheme, not even by species, but rather by means of interaction. He discusses how when we began to cultivate animals, we began to privilege those that have an immediate value for our livelihood or with which we share close relations, e.g. monkeys and mammals. We consider them to be intelligent kin based on the humanity we see inside them, when of course there are also radically different forms of intelligence, even a super-human intelligence—like in octopi—which isn’t thought to be centralized in their brain. I am really interested in the idea of consciousness and intelligence not being embodied either, but being spread across something’s body, as a network of intelligence.

“We tend to conceive of machine learning, AI and big data as all-mighty forces, but it’s important to reiterate that they are extensions of us, being trained by us”

Apparently each tentacle of the octopus has its own brain, which I think makes it a perfect metaphor for the Internet—a bunch of angry fingers mashing keyboards, masquerading as some collective brain.

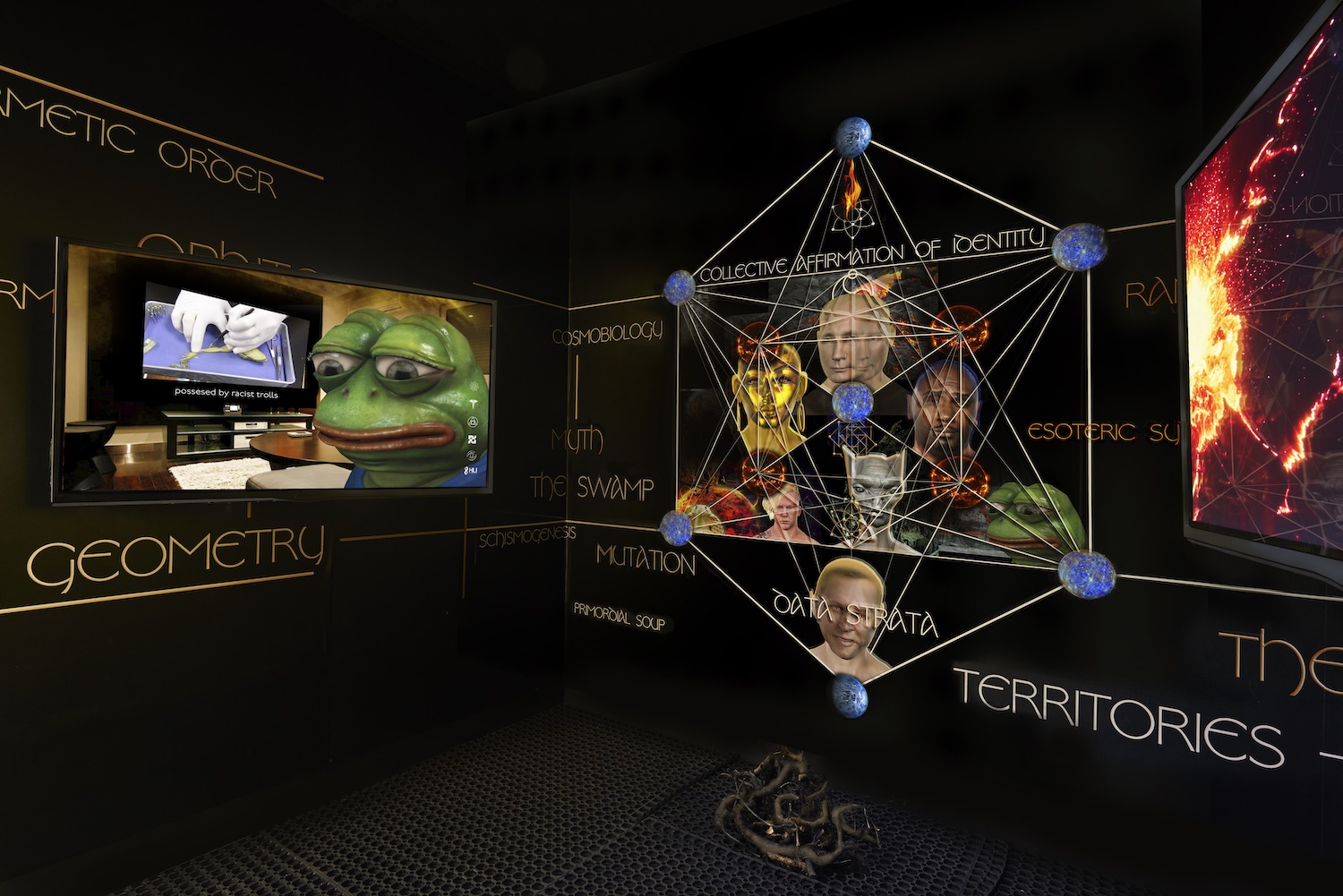

The Internet has totally given birth to its own mythology—people do believe that it’s this higher intelligence because the networks are so vast; that no individual can understand how a computer works in its entirety. We project the idea of this higher intelligence onto this complex system—big data has become this all-seeing oracle, this new god head. If we feed it enough information, it can produce all the answers to something or guide us through the maze of knowing.

“By thinking about biological processes as a piece of technology, it can paradoxically bring us closer to nature, as technology is an immediate extension of ourselves”

Do you think it’s also connected to the resurgent interest in astrology and the occult?

Definitely. The Internet is also a reaction against this technological takeover: how everything is being tracked and monitored—how everything, including our genetic code, is becoming computation. Yet we are still in this deep forest or web of trying to classify or filter all this information out, and the Internet emerges as a powerful feedback loop for our own belief systems. If you have this belief or inkling in something, like how coconut oil cures cancer, you type it into Google and those ideas are reflected back to you.

I read recently that the image recognition data harvested from captchas has been used for years to train AI.

We tend to conceive of machine learning, AI and big data as all-mighty forces, but it’s important to reiterate that they are extensions of us, being trained by us. There has always been a hell of a lot of human labour that goes into birthing these new systems of training robots; it’s very much fed by us, we are parenting these machines. It reflects a certain image of ourselves. But we need to consider who is behind this—who’s the dad? The mom? Who is in power here? It’s not the technology itself that is this evil thing that we give birth to—we are in control of that, and we need to constantly question it.

This feature originally appeared in issue 37

BUY ISSUE 37