It’s not often an artist merges the iconography of Dot Cotton; the sounds of an alter-ego “tranny singer suffering from foreign accent syndrome” named Shitney Cuntstone; ludicrous Vegas booze receptacles in the shape of high-heeled, fishnet-clad women’s legs; and complex scientific collaborations with molecular virologist professors to address the representation of viruses such as HIV. It’s rarer for all that to somehow make total sense, as it does in the case of maximalism proponent John Walter.

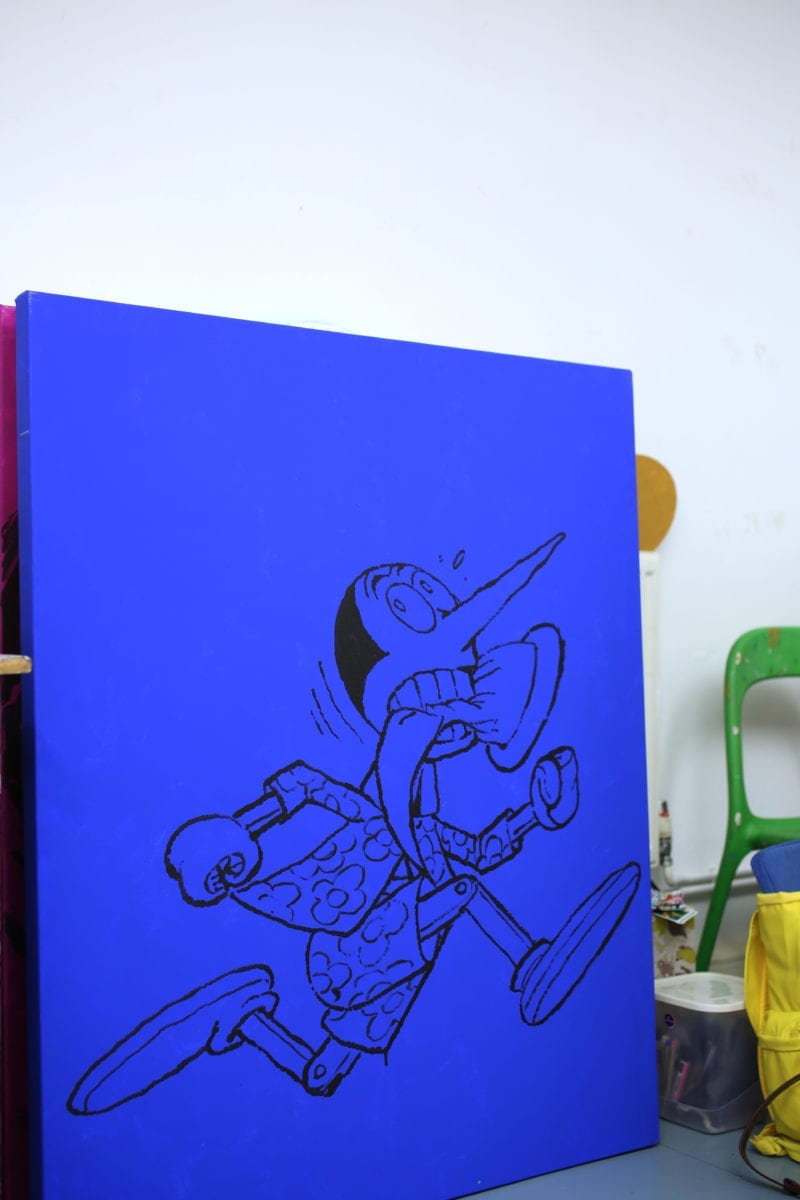

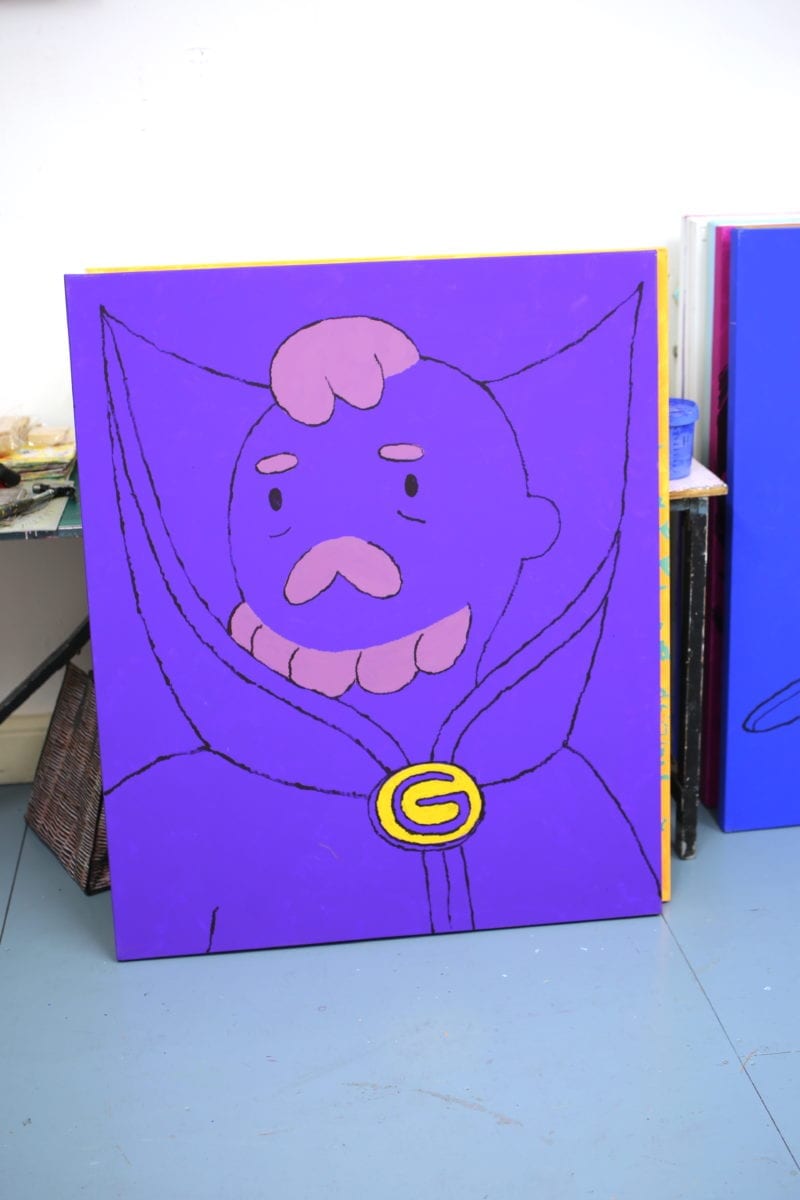

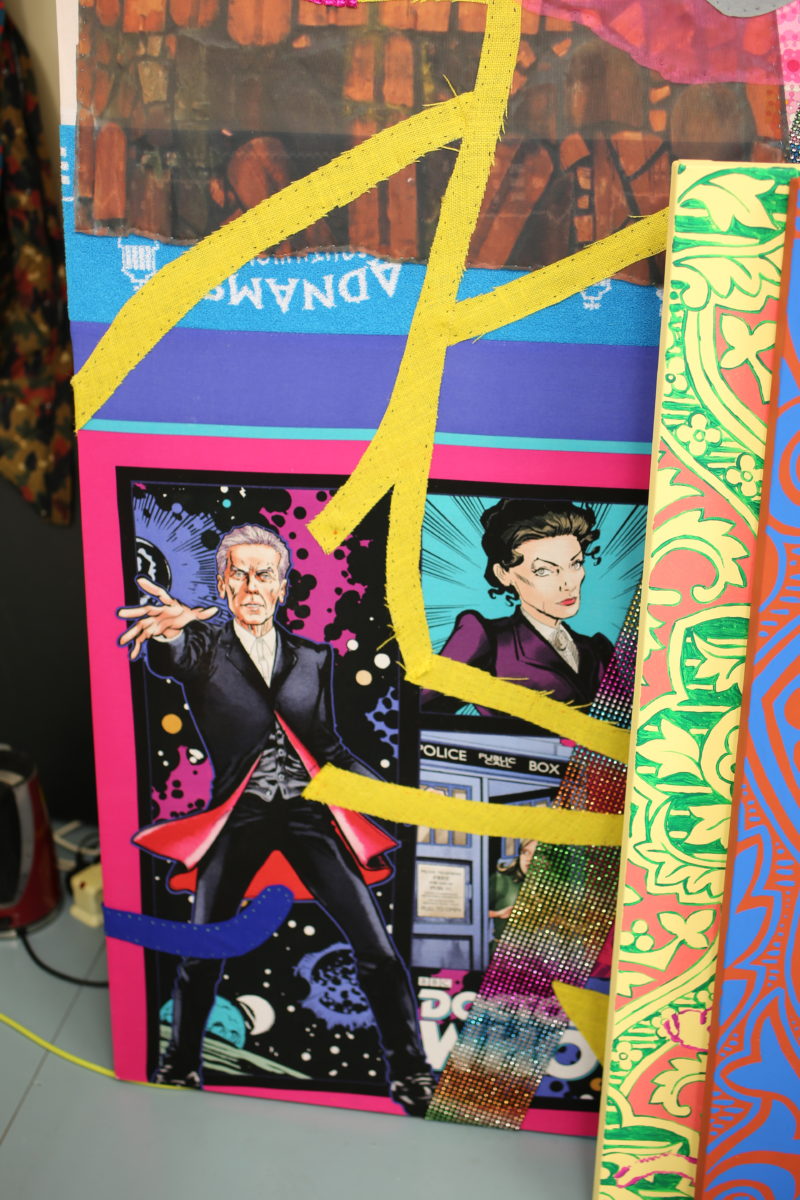

Working from a studio in a labyrinthine complex near Elephant and Castle in south London, Walter’s work is a sublime manifestation of the beauty that comes from sticking two fingers up at the idea that art must always be serious; but also that art is, in itself a form with meaning: instead, he sees art as simply a “communication medium”, he says. “It isn’t anything in itself; I don’t want to make art about art.” Thus, tropes of what many might seem as “low culture”—the garish plastic vessels of Vegas drinking culture, Coronation Street characters, Adventure Time—sit happily alongside investigations into the Gothic Revival, and questions around its implicit connections with Brexit.

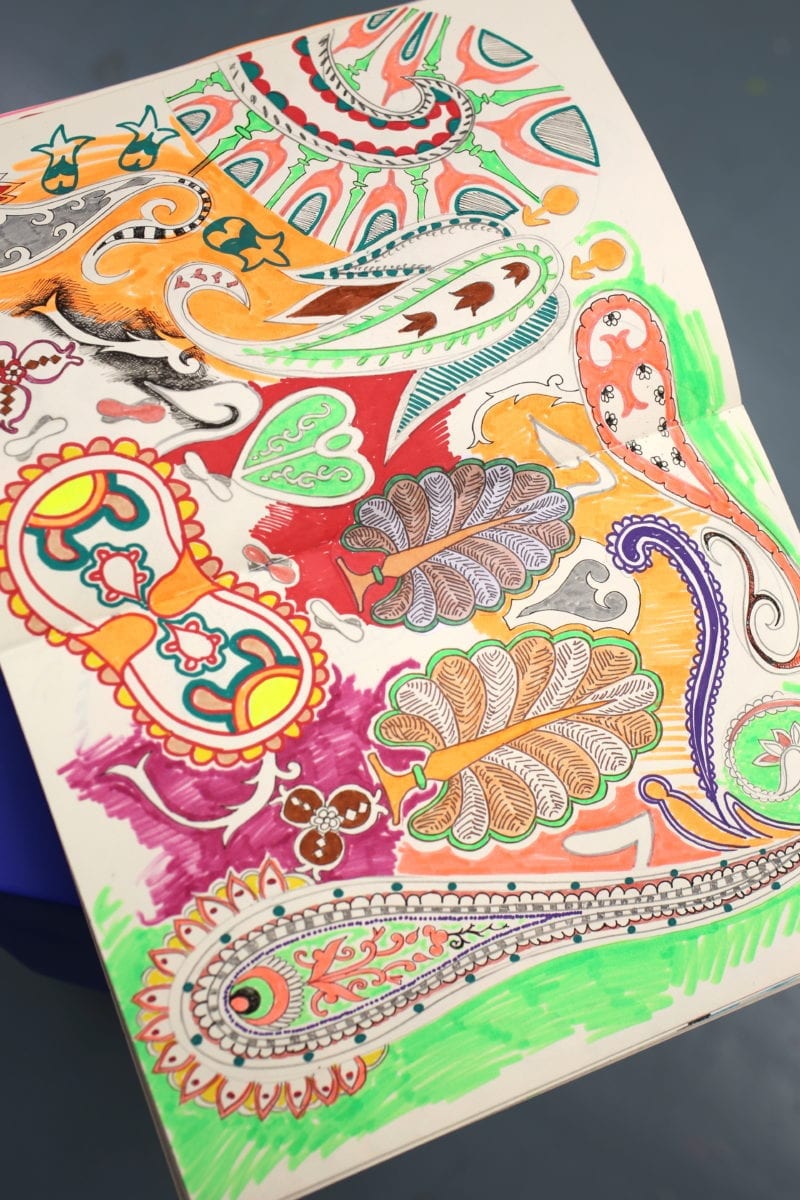

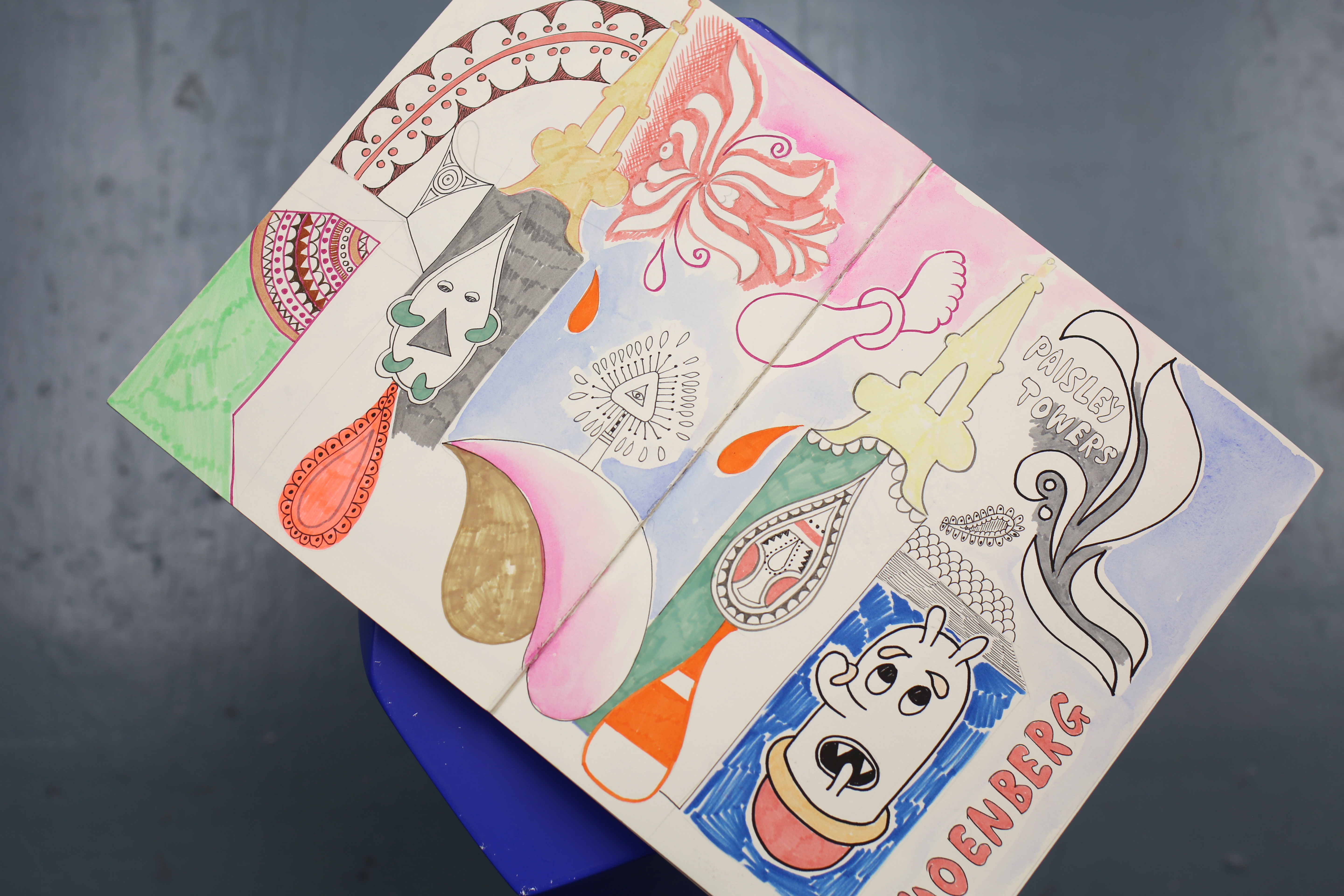

Walter’s current work is is largely focused on paisley patterning, a subject that he speaks about in similar terms to his recent explorations of viruses, as seen in the exhibition Alien Sex Club from 2015—vast and utterly joyful, baffling, brilliant installations that explored HIV through a “cruise maze” mimicking saunas gay clubs. The structure looked to use the methodology of the maze as a place “associated with achieving trance‑like states, risk and addiction”, and within it were fortune-telling performances, free rapid HIV testing for visitors and a series of public events that aimed to provide audiences with “a new vocabulary for understanding and talking about HIV and the factors contributing to its transmission.”

This piece, like Walter’s 2018 Capsid exhibition at Home in Manchester, is based around complex scientific facts—Walter worked with molecular virologist Professor Greg Towers of University College London in an ongoing collaboration to look at the biological makeup of the HIV virus. The piece’s name references Capsids, the protein shells contained within viruses that help protect and deliver viruses to host cells during infection. These were then manifested as drawings, paintings, prints, sculptures, costumes, videos, film and sound. “Virology has a lot to teach us about how ideas and cultural forms are spread, how they inveigle themselves into existence and how they mutate in order to survive. It seems to be that discussion of memes is hackneyed at this point and so going deeper into the science is a way of refreshing the discussion.”

“Virology has a lot to teach us about how ideas and cultural forms are spread”

Virology, strangely, brings us back to Walter’s current focus on the paisley pattern, which spread (like a virus of course) across the world, from its origins across Kashmir and Azerbaijan to Scotland (where its titular paisley name was coined), dovetailing into its 19th revival in Gothic aesthetics and the Arts+Crafts movement. In Walter’s hands, paisley can also take in kids’ footwear stars the Shoe People; and influences from Houses of Parliament architect Augustus Pugin, Italian illustrator and comics artist Benito Jacovitti and Joan Crawford.

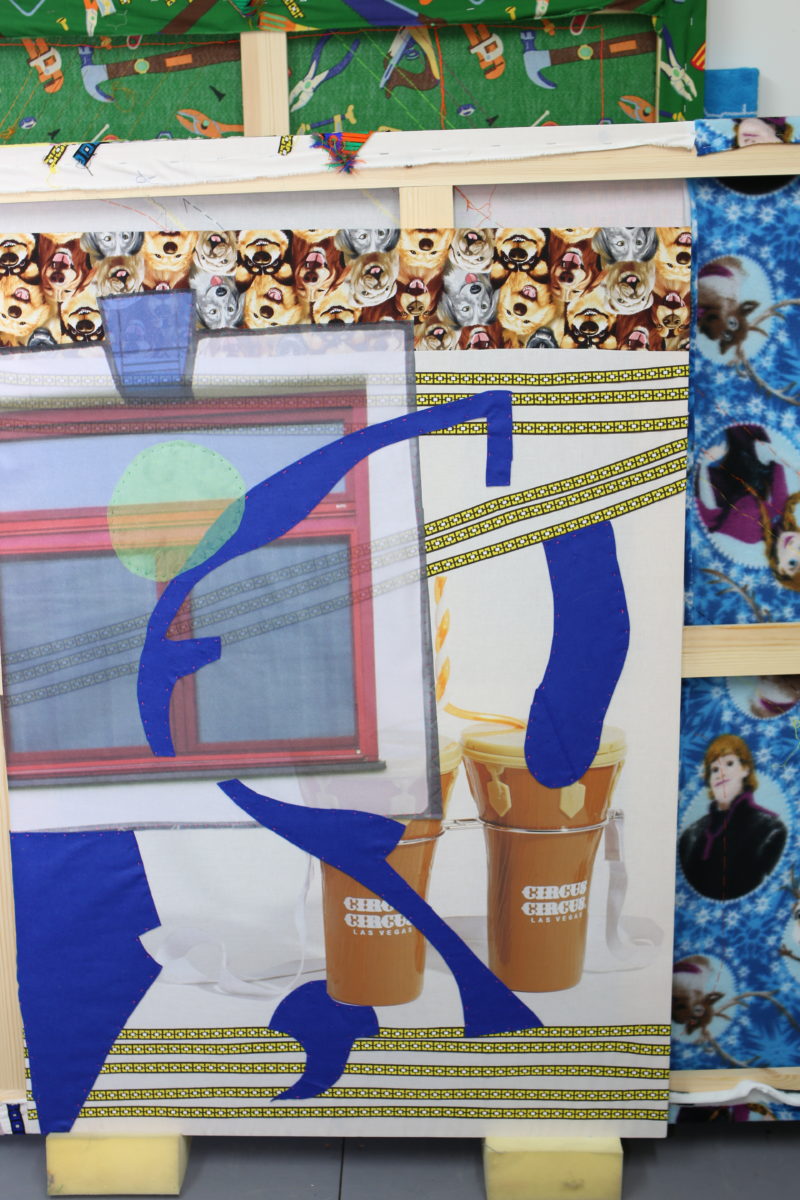

Walter works on hundreds (often literally) pieces at any one time, with multiple series on-the-go simultaneously. Rather than this being a sort of manic, maximalist ADD-like process, there’s method to this madness.”It’s about tripping myself out of getting too obsessed with them,” he says, pointing at some recent fabric-based appliqué works depicting a few “booze objects”, all sewn by hand. “It’s good to take the painting out of the equation for a minute and start to build up painted space just with fabric,” says Walter.

He describes the process of leaving a piece before it’s finished as letting it “cook”; a way of stopping himself “acting too soon” on something. “It’s about trying to get them to resolve in the most unfussy way possible,” he says. “So even though [the pieces] are really busy, there’s actually only three things going on: there’s a foreground a figure and a background, but the background is actually another figure, and the pattern is just another interaction.” He describes an aim to make work that’s “al dente,” something grown out of his “shonky” aesthetic. “It’s the idea of things that are just undercooked, so they’re firm to the bite. You allow the mistakes and idiosyncrasies to become part of it. You own them.”

“Shonkiness”, something Walter has spoken at length about, and curated a Hayward Touring Exhibition around, grew out of the need to describe his production values, “which aren’t slick, but they’re not shit, either,” he says. “It’s about a very precise use of awkwardness—the non-canonical, out of fashion potentially, or perverse—deliberately badly crafted. A good example is when Les Dawson plays the piano badly, when we know he can play it perfectly. So shonky would be letting all the brush marks show. It’s provisional, it’s a stand-in. It’s about rapid turnover of ideas, and it’s punk as well—it’s DIY and low-fi.”

It’s that punkish approach that makes the confluence of TV soap stars and eighties cartoons and booze and virology and the history of pattern design all work so beautifully within the singular approach that Walter has honed. “It’s about one thing bringing the other into relief because of its contrast. It also refreshes it by bringing a new association to it, cross-fertilizing things which aren’t normally meant to be with each other.”

“My natural tastes don’t seem to be what everybody else’s are. I must be naturally perverse”

The artist has often spoken about “bad taste”, something you could argue doesn’t exist. “It’s context dependent isn’t it?” says Walter. “What’s bad taste today could be good taste tomorrow, that’s in constant flux, and there’s hierarchies and flavours, aren’t there—why is one thing fashionable and not the other thing? And why does that change? All we know is it changes, and often the thing that’s in fashion will also be referencing something thirty years prior. There’s a really indexical thing about retro.

“It’s not that I’ve set out to be interested in bad taste, it’s that I’ve happened to be interested in the things that nobody else cared about. My natural tastes don’t seem to be what everybody else’s are. I must be naturally perverse.”

“I’m not sure that there is an identity question within it; in that my identity could change on a dime if I repositioned the parts.” He adds, “200 years ago there was no ‘gay’, and in 200 years time there may be no gay. These things are totally context dependent. So when I put things like Joan Crawford, paisley and Brexit together, it opens up new zones of enquiry for me and maybe for other people by accident. With each set I’m breeding different images, so that’s where putting two things together is the most elegant solution, because it’s literally a hybrid.”

“The humour and the colour and the fun are lures to talk about this other stuff, and they soften the blow. They don’t take away the seriousness”

This hybridity is partially what offers Walter’s work such capacity to explore potentially dark, serious and poignant issues—those surrounding chemsex for instance, as well as HIV. Yet to visit his shows is ultimately incredibly joyful: it’s funny, it’s fun, you leave with a sense of having been part of something, and with a new set of understandings and experiences. Everything is bold, bright, big—maximal, in short—and occasionally pretty daft. “I naturally make this kind of work, and what I’ve found over time is that that doesn’t occlude me from talking about serious or dark things,” says Walter.

“Actually, the two things are indexed to each other in that the tragicomic is a genre. The humour and the colour and the fun are lures to talk about this other stuff, and they soften the blow. They don’t take away the seriousness; it just operates on multiple levels and it offers people the choice of what level they enter in at.”

The vast scale that Walter’s work operates on—often collaborating with a wide range of contributors—isn’t just a vital element to his practice, but one born of necessity. The artist has spoken before about his struggles coming out of art school to assimilate in the art world in the “conventional” ways—gallery representation, exhibition offers and the like.

“I had to be more improvisatory,” he says. “Art school definitely doesn’t prepare you,” says Walter. “You’ve got to be really collaborative and you’ve got to think of yourself as a business—as the head of a team. You are not an island. This is what I mean by ‘I am not a self’: I’m just a particle that stuff glues itself to.”

“Some people will be able to slot into the system that’s presented to them, but some people will be misfits and they’ll have to invent the system. It just depends on what kind of personality type you are. I’m bloody-minded and I don’t want to be told what to do: I want to be in charge. It’s megalomania. But it’s not bad, is it? I’ve got pretty good at it.”

Photography by Louise Benson