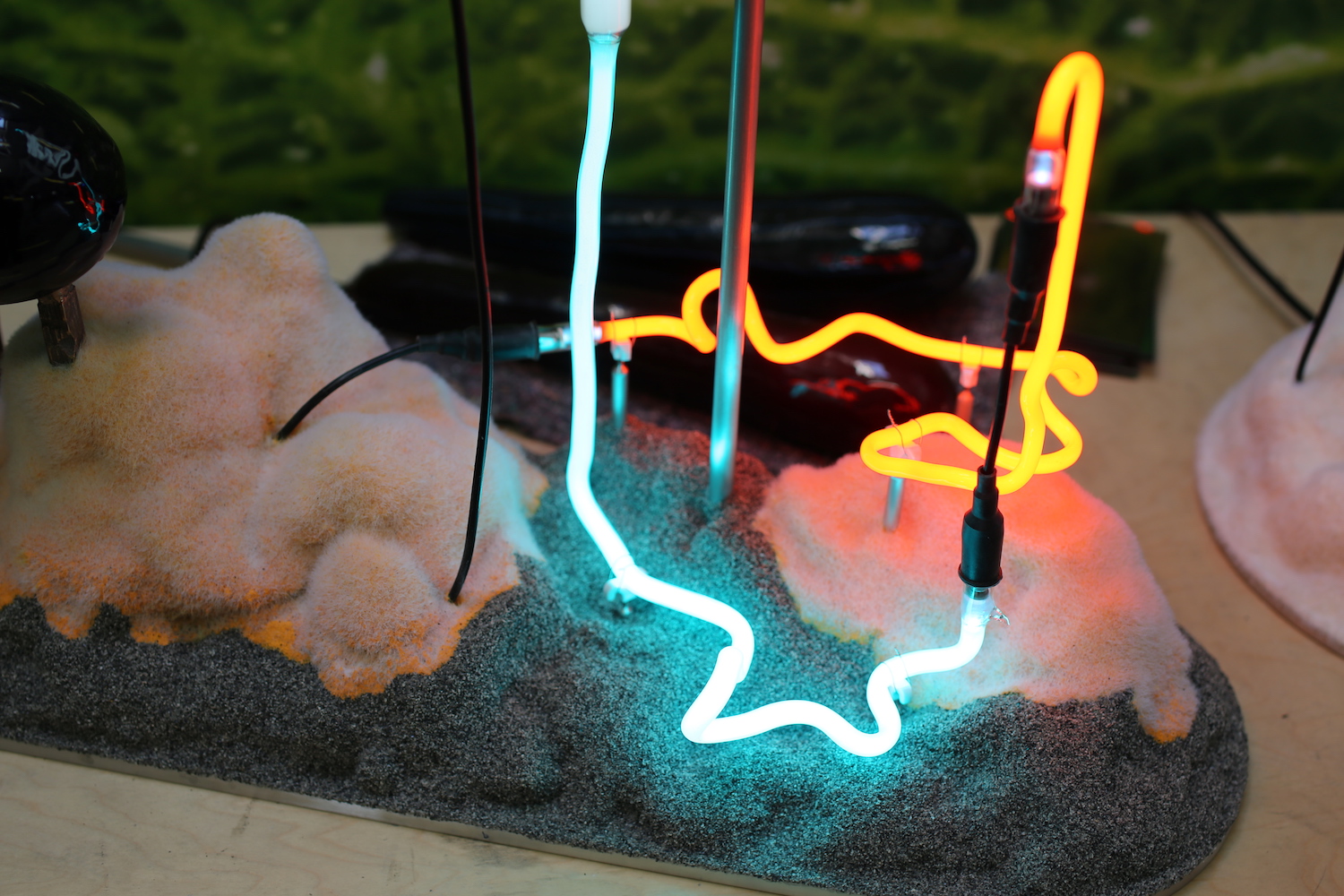

One thing I learned this summer is that Jonathan Trayte’s sculptures stand out in a crowd. If you visited the London Open 2018 at the Whitechapel Gallery, you might have gravitated towards an island that seemed to float amidst the rest of the work on display. Carpeted and alight with a neon glow—complete with droopy palm trees and irregular, acid-hued squashes—this strange technicolour scene was as alluring as it was discomfiting. Or in Dream Work, a five-artist show at Kate MacGarry in June, where Trayte dreamed up giant watermelons that expanded across the white gallery walls, luscious, juicy and impossible to ignore.

I’m intrigued enough to get in touch with Trayte, which is how I come to find myself outside a huge bronze foundry in Limehouse one cold but bright morning, on a cobbled alleyway where old dockside London meets creeping gentrification. His studio of eight years is housed in an old dog biscuit factory adjacent to the foundry. He got the keys to it through connections at the foundry, where he used to work and which he still makes use of. I arrive to find that Trayte has baked a tray of madeleine cakes for us to share, tangy with sourdough leaven and so good that I have three.

We sit down over coffee to talk sexually suggestive neon shapes, a love of foreign supermarkets and his past life as a chef.

How did you start out, and what led you to develop your knowledge of some of the more specialized elements and processes that you make use of in your work?

They closed the foundry the year that I started my undergraduate course in Fine Art at the Kent Institute of Art and Design. So students were losing a lot of the facilities and it became more like self-initiated study. You brought to it what you were interested in. After graduating I spent about four years just working for other artists and exploring materials and processes, teaching myself about different ways of making. It was really helpful, and over that time I didn’t really make much of my own artwork. Then I came to work at AB Fine Art Foundry where I built a new body of work that I then got into the Royal Academy with, and that’s when it really kicked off. I’ve always had an interest in casting. Even way back, I was melting lead on an electric stove in a pan—really dangerous stuff, but it was fun and exciting. That’s why I ended up finding work in a foundry, and it’s here that I’ve picked up most of the things that I know in terms of casting and welding. They taught me a lot.

How has working with bronze influenced your work since, and is it a very costly process?

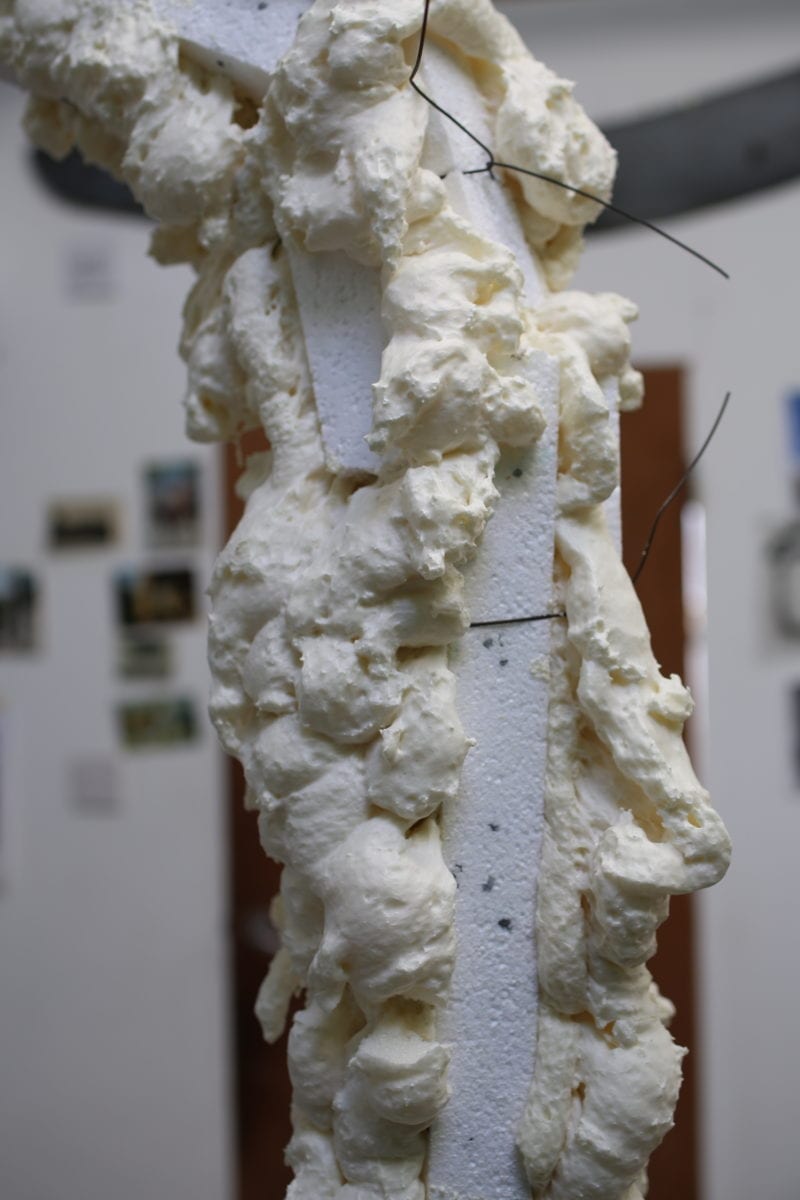

It is expensive. It’s a material that’s usually exclusive to mid and later career artists because of the costs involved and, interestingly, what makes it expensive isn’t necessarily the bronze, it’s the labour. So when you learn the process yourself, you can do all of those things and cut the costs significantly. It means that you can treat it like any other material. What I found really exciting while I was doing my postgraduate at the RA was that I could just play around and make mistakes. It was like a free licence to experiment and not be so precious about the process. It’s how I ended up mixing things like bronze and concrete, or flocked plaster. Working in the foundry has been really informative, and even still working very nearby is extremely helpful. There’s a great team of people there. It’s quite a small group of employees, but some have been with the firm for more than twenty years.

You use a whole range of unusual materials in your work, combining fake fur with cast bronze, resin, plaster or carpet. What interests you in the mixing together of all these ingredients?

I used to work as a chef during my undergraduate studies, and that’s how I got to think more closely about materials and the way we consume; it influences the way I make work. It was in that professional kitchen that I learnt a lot about substances and about how to handle things. There are so many similarities, so many crossovers, between sculptural ingredients and foodstuffs. Like flour and plaster or sugar and crushed glass. They behave in similar ways and have a similar appearance.

Some of these food motifs have found their way quite directly into your work, such as your sculptures shaped like vegetables. How have you developed that relationship?

I often use found objects; things from the natural world. I’ve been borrowing forms from squashes or fruits that I’ve found whilst travelling, or specimens that friends have grown. I have also got to know some growers of giant vegetables too in the north of England who dedicate a lot of time to their plants. They feed them all kinds of weird concoctions and grow huge, obscene things. I borrow the vegetables before the seeds are saved and make moulds, casting them in various materials. Also, I get my references from all over; I’ll spend hours in foreign supermarkets. On a recent trip to the States I found a really nice supermarket on the border of Arizona and Utah. It was just incredible, like going back in time. I collect food packaging as source material and reinterpret it, borrowing colours and motifs.

Looking through these product labels that you’ve gathered together from around the world, they link strongly to consumer culture, graphic design, locality and globalism. How do they influence you beyond the purely visual?

The visual references are regionally specific. For example; colours used for the branding of milk in the United States differ ever so slightly from what we are familiar with in the UK. I find these discrepancies really exciting. Colour is so important as a means of persuasion in advertising, persuading people to consume in particular kinds of ways, or in appealing to specific social groups. I create synthetic painted veneers that reflect this language; they’re like skins of paint that create a kind of chameleon appearance.

There is often a thin line between attraction and repulsion in your work. How do you choose the varied materials that you work with, and what attracts you to gooey, melty textures and these contrasts…

I like making work that has an appeal, an attraction, but I also like for there to be a bit of a conflict. Nothing’s ever perfect. There’s always a bit of grit somewhere, a fly or a hair. I always like to have something unsettling in the work. Whether it’s a hairy background texture, some weird ugly bronze cast, or a sexually suggestive neon shape, maybe a boob in there… I do always like to include that kind of thing.

Your recent solo show at Friedman Benda in New York took a different direction, venturing into upholstery and soft furnishings. What was the thinking behind it?

It was a real whirlwind. I only had four or five months to get the work ready to ship, and it was a hell of a lot to make in a short space of time. I didn’t really have long to dwell on the concept at the planning stage, I had an idea and I ran with it, experimenting through making. Ultimately the plan was to build a surreal apartment, but to bastardise it and challenge my notions about domestic space, turning it into a bizarre environment full of varying colours and textures. Ultimately I’m conflicted though, because I want these pieces to go out into the world and to be used. It’s all well and good making a weird two-legged chair that doesn’t even stand up, but no one’s ever going to be able to use it. So I do feel the need to conform to certain aspects and limitations.

It’s interesting that you want people to use these objects rather than just look at them, and they really cross the line between art and design. What appeals to you about the combination of the two?

All of these pieces are still very sculptural, but their accessibility and usefulness in life is also a new aspect to my work that I find really exciting. It’s a fresh challenge to take on. This is not to say that I consider myself a designer now—I’m definitely still an artist—but I like the fact that I can switch between the two disciplines. It seems funny even having this discussion about whether there is a difference between them, because there really isn’t. For me, making a piece of work, whether it’s a sculpture or a chair, is quite a big investment—both financially and in the time spent constructing it too. I love the idea that someone might want to use the thing, and so for me that is an important part of it.

All photography by Louise Benson