In Jordan Casteel’s Noelle, her subject sits forthright yet relaxed in a light bedroom, the patterned duvet spilling out of shot like fragments of a drifting icecap. The image, from Within Reach, Casteel’s exhibition at the New Museum in New York (paused during lockdown), is one of the more recent works in the display. The show also includes canvases from Casteel’s Nights in Harlem (2017) and an ongoing selection of studies from the city’s subway, begun in the same year. Unlike Noelle, with its three pairs of eyes staring down the viewer, Casteel’s commuter paintings feature Black figures turning away, or with their faces left undepicted. Casteel’s purpose remains consistent across the exhibition: to extricate her subjects from the inequality and stasis of everyday life in America, and to glorify the multiplicity of Black experience.

The earliest works in Within Reach are taken from Casteel’s 2013-14 series Visible Man; for this, shortly after George Zimmerman was acquitted of killing Trayvon Martin, Casteel painted her male peers at Yale University. Observing a deficit of humane portrayals of Black men in the contemporary media after the killing, she sought to “paint Black men as I see and know them… As my twin brother, as my older brother, as people that I love,” using busy domestic settings and sheer scale to create her trademark intensity.

“Casteel disentangles her subjects from the temporal dynamics of American life in order to create a newfound intimacy”

Her New Museum exhibition positions these portraits alongside recent studies of Casteel’s students at Rutgers University—like Noelle. Originally shown at Casey Kaplan gallery, the newer works continue the artist’s examination of Black subjectivity as it exists prior to institutional categorisation. As with Visible Man, Casteel disentangles her subjects from the temporal dynamics of American life—whether educational, professional, or social—in order to create a newfound intimacy. In aiming for timelessness, Casteel’s vibrant use of colour elevates her subjects from the transhistorical moments which often group African Americans into stringent, joyless categories. She captures the images on camera and then paints from the hundreds of resulting shots, using greens, blues and oranges to render the diversity of Black bodies.

These works were originally titled The Practice of Freedom, after bell hooks’ 1994 book, a critical manual which encourages educators to empower students to transgress social boundaries. Casteel describes the paintings as allowing her to “[see] all the cultural differences and personalities” of her students, and to “recognise that knowledge exists before I even enter the space”. It’s this idea of existence preceding the artist’s gaze that unifies the work in Within Reach.

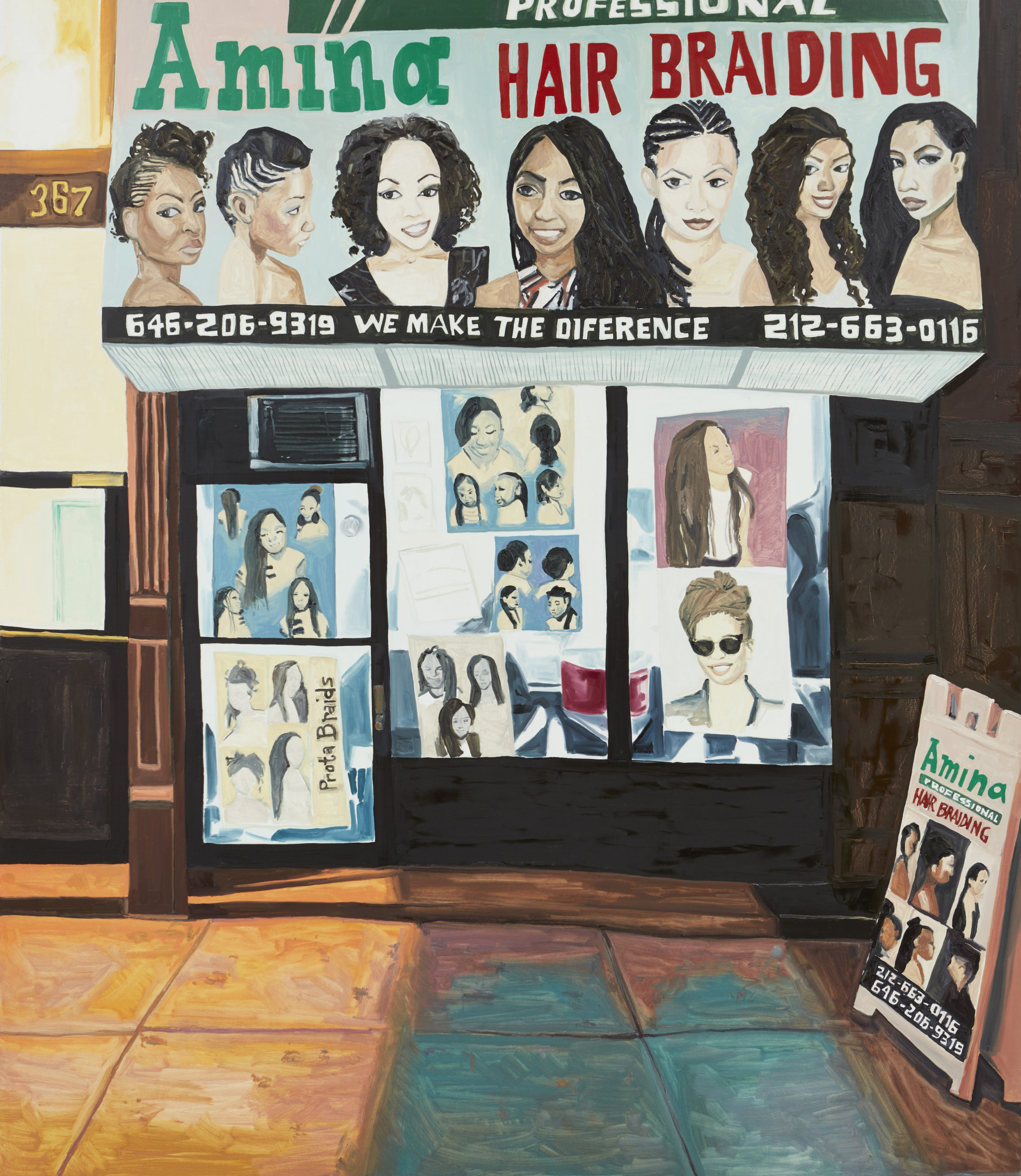

“ She paints the detailed signage of a hair-braiding salon and clothes vendors, maintaining close contact with her subjects”

Casteel’s more involved images from Nights in Harlem form a diary-like series that signposts the bustling community around New York’s 125th street. Here, Casteel paints the detailed signage of a hair-braiding salon, clothes vendors and siblings running a bar and diner, maintaining close contact with her subjects throughout the creative process. The cultural detritus of American commerce is unavoidable. In one painting, James, a street vendor, sits proudly on a white stool selling CDs, his foot resting on a Fender amp while a hulking Chrysler saloon dominates the background. In Noelle, the unmistakable Wonder Woman cushion makes an absurd accomplice to the main figure, whose awkward hand positioning and windowsill picture signal unapologetic youth.

When the New Museum does open its doors once again, it will do so to a changed racial landscape. But Casteel’s power is to look beyond prevailing socioeconomic or racial narratives; in examining Black existence as lived rather than as trend or news bulletin, she conveys a hopefulness which the white American gaze—with its institutions, values and social systems—still fails to actualise.