“I rarely make paintings with a set, initial plan. They start as abstract forms and it becomes this intuitive, primitive, dance—a dance in the dark,” Jules de Balincourt tells me in a warm office at the back of Victoria Miro Gallery in Mayfair. It is bitterly cold outside, about 4C, but it feels tropical, he says, compared to the big freeze gripping the American east coast. He lives in “dark and dreary” Brooklyn, but that is hard to believe when standing in front of the sunny yellows and neon pinks of his canvases, which are populated by crowds of tiny people in strange, dream-like landscapes. “Painting is a form of escape. I just dive into the unknown and see where it takes me. You’ve got to just trust it. I’ve done it for twenty-five years now.”

“It has been complete chaos for America. You can’t put it into words. I check my phone in the morning, half expecting to hear that North Korea has been nuked.”

De Balincourt’s azure seas and pink mountains certainly offer escapism from the grey beyond the gallery walls. Does he like London? “I am surprised by how much more integrated people are in England. In America it is a melting pot, but none of the ingredients are mixed. It is still heavily ghettoized, even in New York. I live in a Puerto Rican neighbourhood,” he points to an imaginary map on the table. “Jews live here, Polish people live here, the hipsters live here and black people live here. We’re all there but we’re definitely in different little camps.”

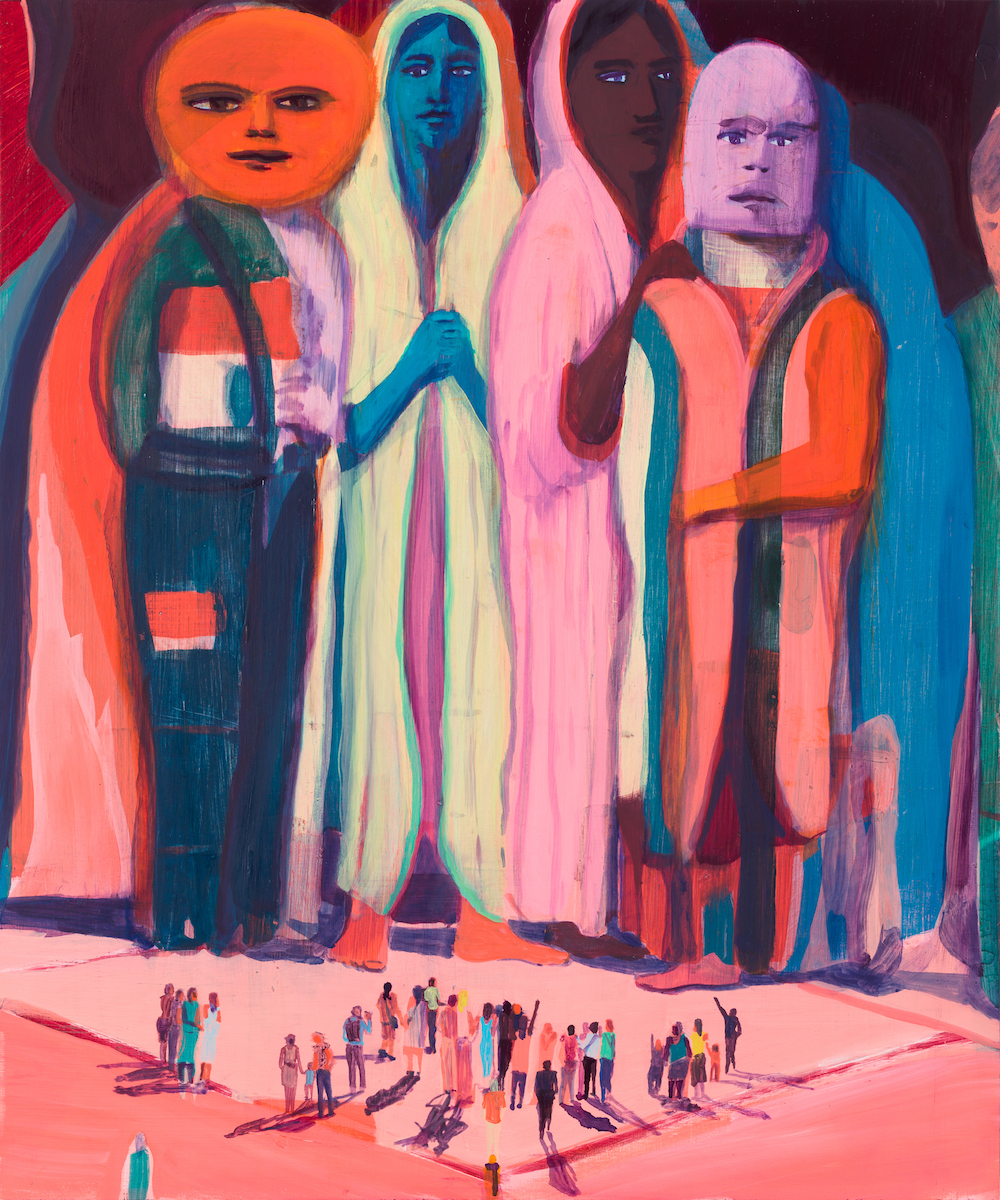

Big Little Monsters, 2017

It is a year to the day since President Trump’s inauguration when we speak, and talk turns to the last twelve months. “It has been complete chaos for America. You can’t put it into words. I check my phone in the morning, half expecting to hear that North Korea has been nuked. That’s the reality we’re living in.” Has this feeling, I wonder, worked its way into his paintings? “I think subconsciously, but my work is not directly confronting it. The anxieties and the uncertainties are there a little bit. If you want to make beautiful things, how do you confront the Trump thing directly?”

But I have spotted Trump in one of the paintings, his body strangely swollen, as though he has been inflated with a bicycle pump. His face is the colour of a traffic cone and his hair impossibly yellow. He is pointing his finger, wagging it at a line of black men. He is not alone; other pink-faced men echo the President’s profiles, and, barely noticeable, a tiny crowd cheers from the bottom of the canvas. I mention my sighting. “Oh, yes! Repeated Histories. That is a reference to when he was denouncing the football players for kneeling before the game. They were protesting against police brutality, they were kneeling in solidarity.” Trump made it clear at a campaign rally in Alabama that he felt that it was unpatriotic to kneel during the national anthem, that the players were “disrespecting the flag”.

The more we talk more about the paintings in the exhibition—all made in 2017—the more it becomes clear that the year’s events have crept into much of de Balincourt’s recent work, sometimes plainly, sometimes much more subtly. Cave Country depicts a large limestone cavern with a bright, fleshy pink interior. A crowd gathers inside, bathed in a warm light. These people are sheltering, if not in a literal cave, then a symbolic womb, a place of safety. Could the cave be an idea, a comforting, common vision? “It’s a cosy little refuge, but perhaps people are hiding from something,” de Balincourt tells me. “I like ambiguity and leaving the interpretation to the viewer.”

“I like to make hopeful, beautiful things, you know.”

I ask about another painting in the exhibition that seems to echo current events. And The Horse You Rode In On depicts a large pink statue of a man in a cowboy hat riding a horse. A crowd of tiny people throw up their arms, seemingly in celebration, while arches of fireworks fizzle overhead. It is a beautiful image, built up with thin washes of oil paint that are applied, sanded back and applied again, until the scene glows with a celebratory light.

The man on the horse, de Balincourt tells me, is Roy Moore, an outspoken Republican who ran for a Senate seat in the state of Alabama amid allegations of sexual misconduct. He rode to the polls on horseback—which resulted in much chiding on social media—and lost to Democrat Doug Jones. De Balincourt seems to be mocking Moore’s hubris. And there’s a nod to the wave of Confederate monuments that were pulled down last year as a reaction to a mass shooting by a white supremacist at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in South Carolina.

“It has been such a crazy time.” Is he optimistic about the future? “Not really. It’s hard to be. Trump has brought out the dark subconscious of America. All of a sudden it came to the surface, the racism, the bigotry, the misogyny. It has created a big split, an identity crisis. But great things are coming out of it. There has been a new wave of feminism, the woman’s movement, the ‘me too’ movement.”

What would it take for the French-born artist to leave America, I wonder, but before I get the chance to ask, he tells me he is buying a house in Costa Rica. “I’m not leaving full time, but I like the idea of spending part of my life down there and escaping the craziness of New York.” He plans to start an art residency in the coming months and likes the idea of being more self-sufficient, plus he is familiar with the country. “I’ve been going there for twenty years and one of my best friends lives there,” he explains. De Balincourt might not hold out much hope for the future of American politics, but he agrees that his is an optimistic palette. “I like to make hopeful, beautiful things, you know. I’m not painting violent things, I’m not trying to shock. Art is about beauty and seduction and aesthetics, but it is also about ideas and questions.”

Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London / Venice © Jules de Balincourt