Through poetic repetition, moving image, and a resonant sense of memory, Julianknxx’s latest exhibition at Buro Stedelijk transforms fleeting performance into a spiritual archive.

Last spring, nine singers dressed in vibrant red gowns and headscarves performed on the steps of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. As they stood underneath the arched entryway, their voices resonated throughout the institution as hundreds of visitors watched in awe. It was a sacred experience that moved curator Rita Ouédraogo to tears. “I’ve never cried while working here, especially not on the opening night when I’m the one hosting,” she says as we speak in the same corridor where the performance by the revered British-Sierra Leonean poet, artist and filmmaker Julian Knox (known professionally as Julianknxx) took place. “I was sitting here, and all of a sudden I was like ‘Oh my God, I feel tears in my eyes’—something really special happened.”

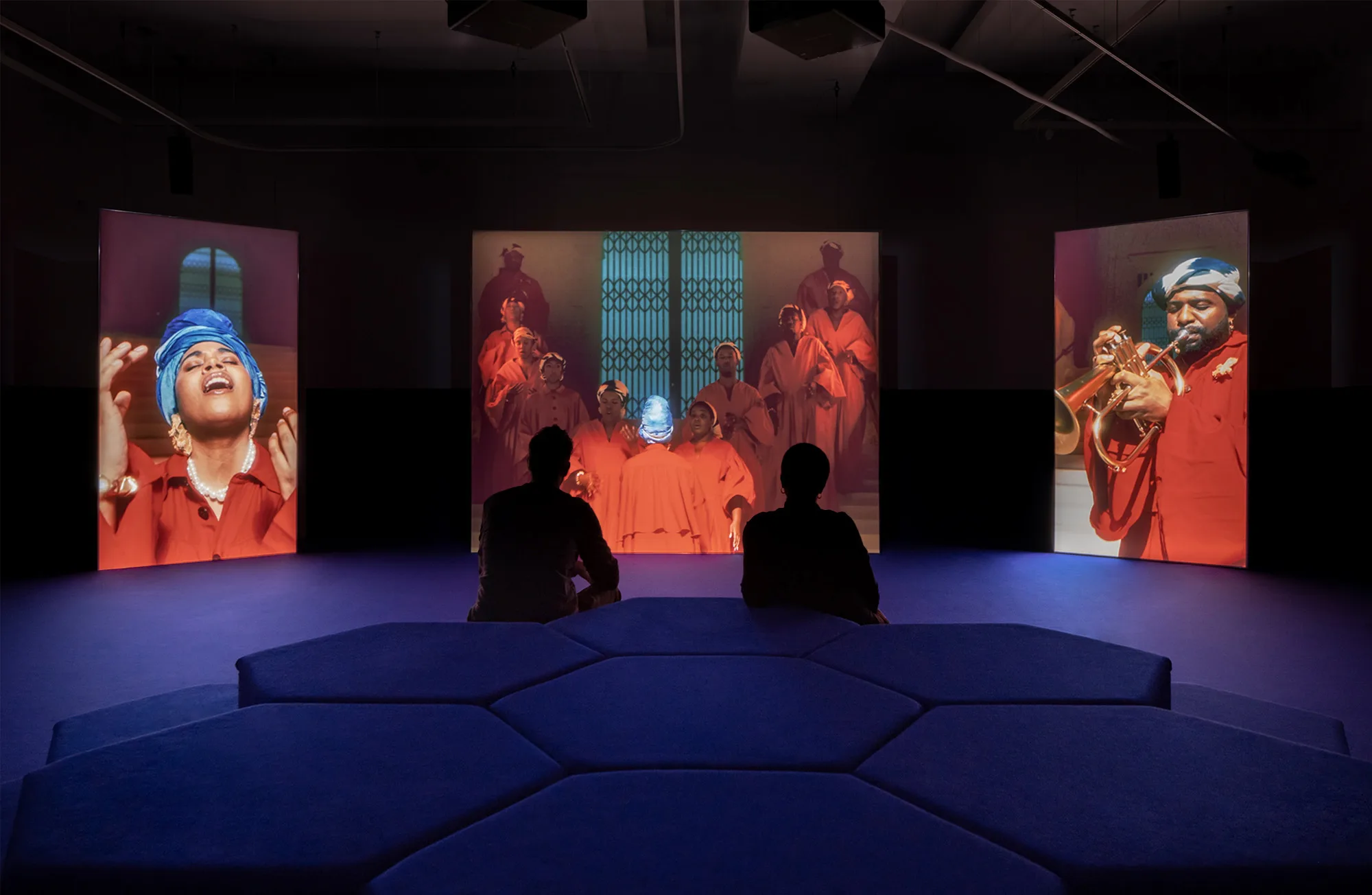

Chorus in Flight, performed last May, featured Memoria Collective, a group of artists from Suriname, Curaçao, and Cape Verde, in collaboration with the creative platform Metro54. It now serves as the jump-off point for Knox’s most recent work. Taking place at the Buro Stedelijk, a hybrid project space in the museum, SHIFTING | SPIRIT | TIME is a multi-screen installation and exhibition that builds on Chorus in Flight, exploring how such an ephemeral experience can be documented and studied. “This was an opportunity to see how to capture the spirit and the emotion of that time,” the 38-year-old London-based artist says, dressed in an orange knitted beanie hat and white shirt hours before the show’s opening night. “The title is a line from a poem I wrote, and it’s looking at how we can use non-language, repetition and music to shift our body and time.”

In the core installation for SHIFTING | SPIRIT | TIME, the choir—dressed in the same gowns they wore for Chorus in Flight—repeat the refrain “wai,” a word that exists in many forms and in different languages and cultures. Across three highly illuminated large screens in a dark room, the singers fade in and out of view creating a surreal meditative experience. “In English, ‘way’ denotes this idea of a pathway or finding the way: what is the way, where is the way, what is the way beyond this space?” Knox explains. “But in French, ‘ouais,’ is ‘yes.’ Then I’m sure if you go to Asia, it becomes something else.” The repeated phrase becomes almost comforting simultaneously encompassing all possible meanings and none at all. “At the beginning of this, ‘wai’ was a holding word to get to the poem or song that I was trying to make, but it held the spirit of what I was trying to do—so much so that it made me rethink my use of language,” he adds.

For much of his artistic career, Knox has used poetry, music and film as a way to explore human experiences (especially those of Black people) and how they are affected by societal structures both historically and in the present day. But artistically, he has never been one to spell this out to viewers explicitly, often offering works that challenge ideas around identity or that inadvertently explore certain historical narratives, such as race and trauma. “We don’t say it in the digital press release for the show, but of course, it’s touching on these things,” Ouédraogo adds. “That’s also part of why it resonates with people or why I got very emotional about it—because it touches on something that you don’t necessarily speak of all the time.”

Knox’s complex and engaging practice has seen his work exhibited across the globe especially in Europe. His recent shows include his first institutional solo exhibition, Chorus in Rememory of Flight, at the Barbican in London in 2023; his participation in World in Common: Contemporary African Photography at Tate Modern; and exhibitions at Matadero in Madrid, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon, Franklin Street Works at Stamford, Connecticut and Schinkel Pavillon in Berlin.

However, exhibiting at Buro, designed to encourage experimentation, gave Knox the freedom to approach his practice in new ways. “You’re there to try something different, something that you haven’t done before or that you’re interested in doing,” he explains, “and, within my practice as a poet, looking at performance and moving image, the poem often exists first and then comes the melodies and then I translate that into music or a performance in a space or a film.” Instead of adhering to his usual process, Knox decided to consider what it would be like to archive his performance for someone to later replicate. He wondered, “What it would be like to study my own performance or put it down in a way that when I pass it on to someone, they can do it themselves?”

The exhibition space opens with a six-minute video on loop titled And If A Tree Sees It All (2024-2025). The installation weaves together poetry and various moving images sometimes layered on top of each other to create a piece reflective of the act of remembering. “The way memory performs is not linear,” he says of how he decided to present this piece. “I think moving image gives me the grounds to play with that—if you keep layering these images and thoughts and repeating ideas, then hopefully it opens up a curiosity.”

The piece particularly centres around “De Boom Die Alles Zag,” which translates to “The Tree Which Saw Everything” in Dutch. It refers to a grey poplar tree in Bijlmermeer, a high-immigrant neighbourhood in Amsterdam. In 1992, a plane crashed into a building in the area officially killing 42 people, though that number is thought to be higher due to the undocumented and unregistered people who lived there not being accounted for. The surviving tree next to the incident subsequently became a memorial site for its victims. “It reminds me of so much of Grenfell–it was fire and this was a plane crash,” he says, pointing out that the film shows how the government at the time failed to document the incident well or treat it with the care and sensitivity it deserved. “The tree stands as a memorial, but also as a way to archive the dead, which I found beautiful and profound as ways in which black people archive themselves,” he adds. “Even if governments or institutions don’t do it, we can find other ways.”

Knox also used the opportunity with Buro to dabble with objects—something that is unfamiliar territory for him and a significant way in which he has deepened his practice. For him, the show was an “opportunity to add another dimension,” he says. “I can now begin to study objects as a way to carry knowledge. I think that’s something I’m excited about for my next project.” He used stone to create a blueprint of the formation of the singers in Chorus in Flight, another had “wai” written continuously. “I didn’t want it to be a thing where I’m just taking stills from the film. I wanted it to be like a study in itself,” he says, “I feel lithography speaks to me thinking about printmaking as a poet and print as an object.”

With such lofty subjects at play, I ask Knox what he hopes people gain from the show, but he notes that part isn’t up to him. “If the people I’m working with are satisfied with the work and the story we’re telling together, then I consider the work done,” he says. “The work is made in collaboration with many, and now it stands as an offering to the world.”

Words by Precious Adesina