ArtBo cultivates a pleasant feeling this year, focusing on the rurality of its home city of Bogotá. “Bogotá is not a modern city per se. Being both rural and urban is what makes it so fascinating,” says Beatriz López, who is part of the fair’s selection committee. It is recognized as one the greenest cities in Latin America. For example, Mayor Enrique Peñalosa is responsible for restricting private car use, building hundreds of kilometers of sidewalks, bicycle paths, pedestrian streets and parks. The capital city of Colombia is also surrounded by mountains. (A note about that, if you happen to be visiting you would be well served waiting two days before starting any physical activity. The altitude—8,660 feet above sea level—can easily make you feel dizzy. I almost fainted from running up to a colleague on my first evening there.) There are more than 1,100 urban green spaces in town. Almost all the galleries I visited before tackling ArtBo included a courtyard. With that in mind, I noticed a proliferation of nature-orientated works—even Maria Paz Gaviria, the director of the fair, was clad in a flower-patterned dress on opening night.

Carlos Cruz-Diez at RGR+Art

The first installation in sight, the one which literally opens the fair, looks like a rainbow-toned forest. Entitled Transcromía, it is made of see-through, though tainted, plastic sheets, likely to wake up the child within you. Together they create a colourful labyrinth. It is part of the section Sitio, meant to tie the fairgoers to the space they are about to explore. Which is exactly what Carlos Cruz-Diez’s work is all about. He is considered one of the most important exponents of kinetic and optical art in Latin America. His commitment to the environment lies in the way he uses light and movement to deceive the viewer. The red wall you stand in front of may turn orange if you look at it from different angle. Take a right and, in line with a blue partition, it suddenly becomes purple. The chromatic combinations are here infinite, which makes it so much fun to meander through this ever-changing landscape.

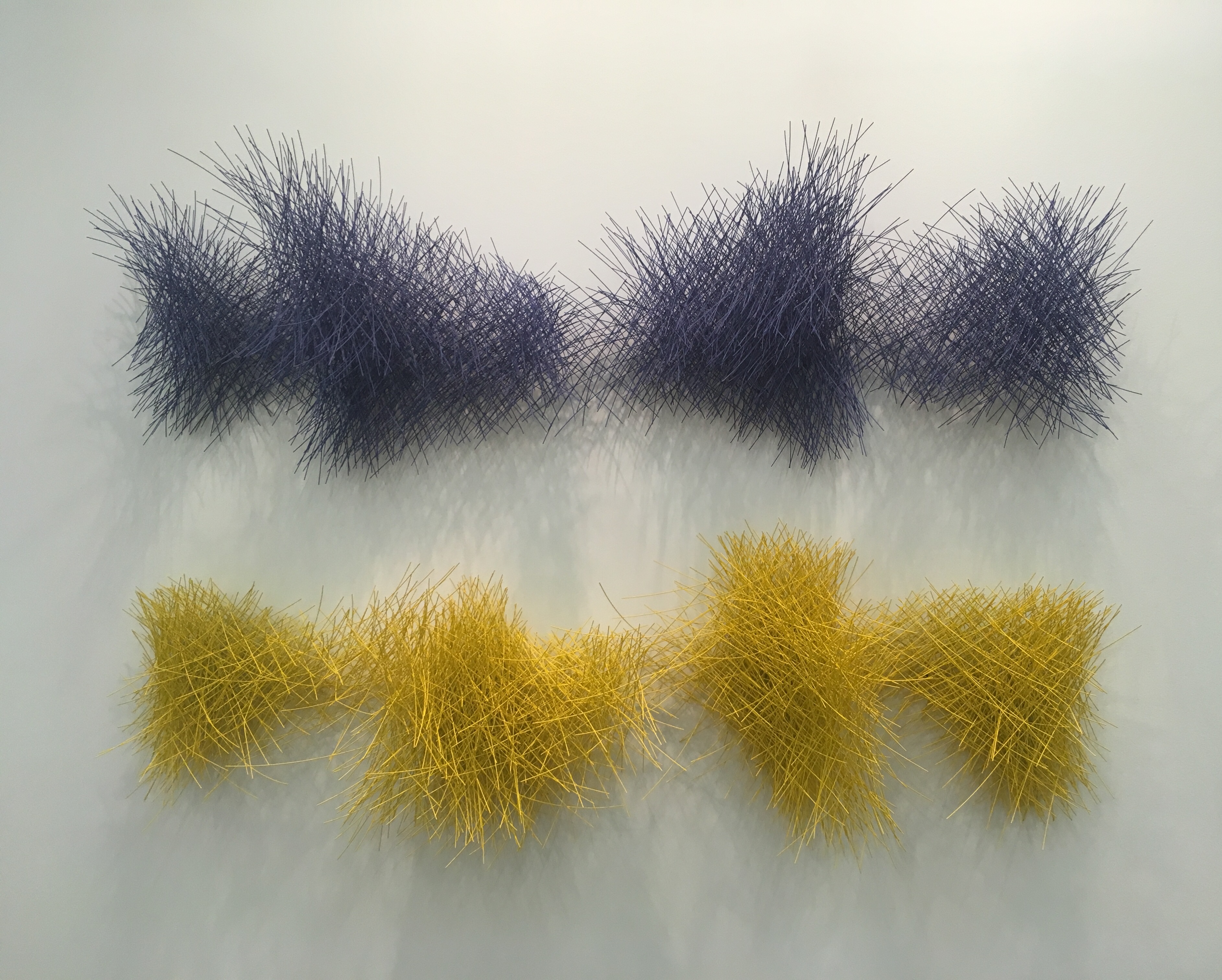

Ricardo Cárdenas at La Cometa Galeria

The gallery’s name alone hints at a strong interest in natural phenomena. So it only makes sense that the institution named after those “dirty snowballs”, as they are commonly called, would represent an artist such as Ricardo Cárdenas, who draws most of his inspiration from nature. His sophisticated structures in steel and aluminum question the dynamic relationship between man and nature, science and art. One of my favorite pieces by him, Nube Amarilla (Yellow Cloud), may convey, in light of its title, the image of a surprisingly luminous fog. Yet its colour and texture makes it pure abstraction.

John Nomesqui at Aurora Espacio Para el Arte y el Diseño

In the midst of the Aurora booth stands a tree trunk wearing an immaculate coat. Which reminds me that it is raining outside. Forget about sunbathing in Bogotá right now. Back to this highly original piece of clothing. It is actually paper-woven, a technique which John Nomesqui specializes in. Nominated for the Premio Mesoamérica al Arte, this Colombian artist is known for his ecological approach to art, not to say life. This installation belongs to a larger series named Consumo Cuidado (I Consume Carefully), which promotes manual work over machines and sustainable development in the world.

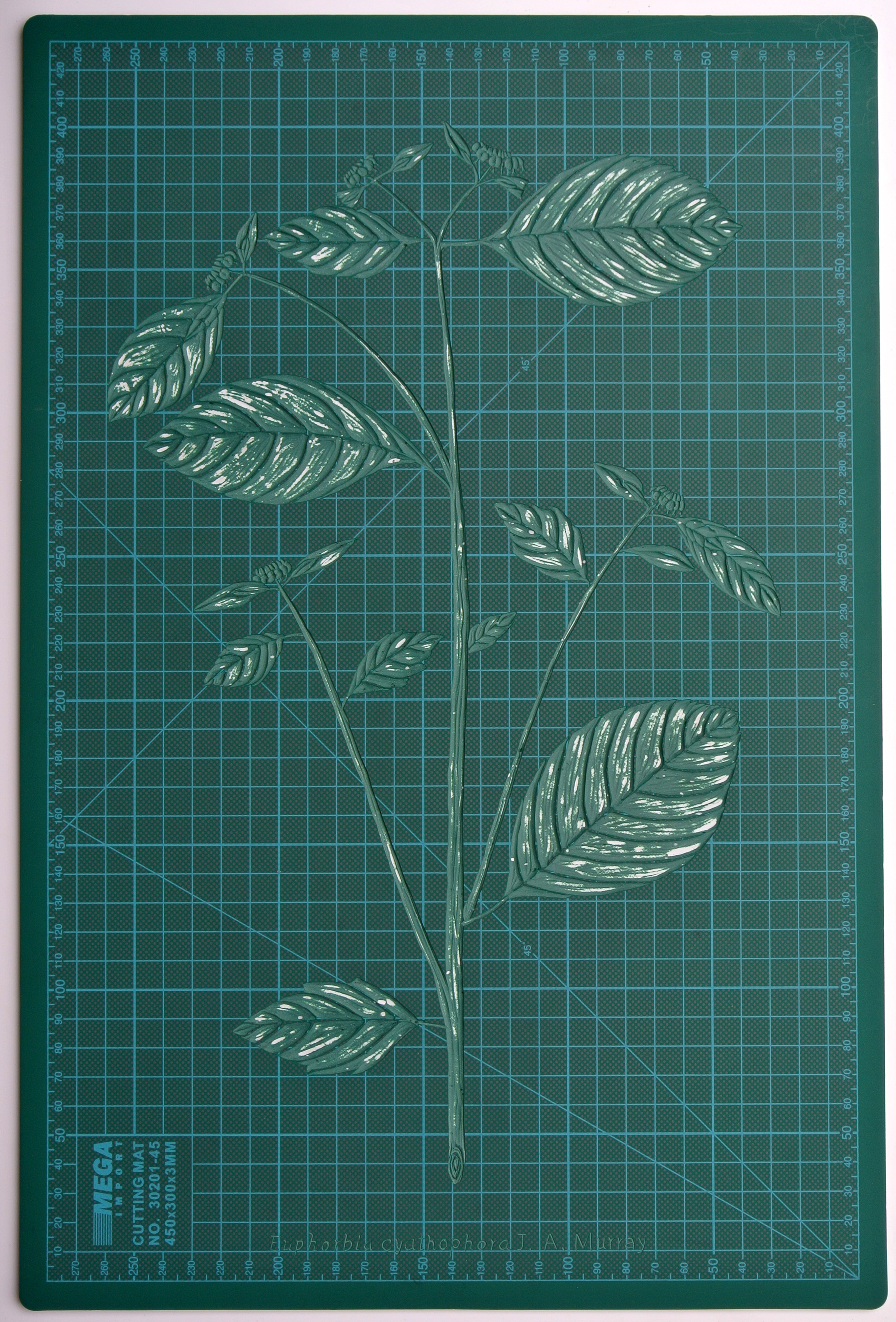

Evelyn Tovar at Otros 360°

Evelyn Tovar believes in progress, she is just not sure about how much it should cost society. Any construction site usually comes with the destruction of its surroundings. Maybe there is another way? Why not try to fuse architecture and nature? This is exactly what a piece such as Euphorbia Cyathophora does. It consists of a map where the artist has carved the shape of a supposedly extinct plant, to symbolize the threat which civilization sometimes entails. The deeper she scrapes into the green surface, the whiter it gets, therefore taking up the appearance of sap. Is it necessary to bleed the living substance out of trees? Other works by Tovar raise the same question, such as Contractura. This black-and-white serigraphy shows a chunk of brick thrust in the middle of a tropical forest. It alludes to the way Occidental explorers used to plant flags to claim some unknown land. Are we going to cover the entire planet with buildings? There won’t be much green left on our world maps.

Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë at Abra

This Venezuelan artist has been living amongst the Yanomami, who are one of the best-known forest-dwelling tribes in South America, for almost thirty years and his artistic creation looks to honour the ancestral traditions of this community. In addition to numerous publications on the matter, Sheroanawë produces drawings on paper he has had made especially for him, from cane or plantain leaves. This untitled figurative piece has a positive meaning. It features a seemingly dead tree, except that the white dots on it are an indicator of life. They represent mushrooms which were able to grow back on the tree bark. This kind of resurrection can only happen if the surrounding soil is healthy. It took the tree’s decay to realize that its surroundings were viable.