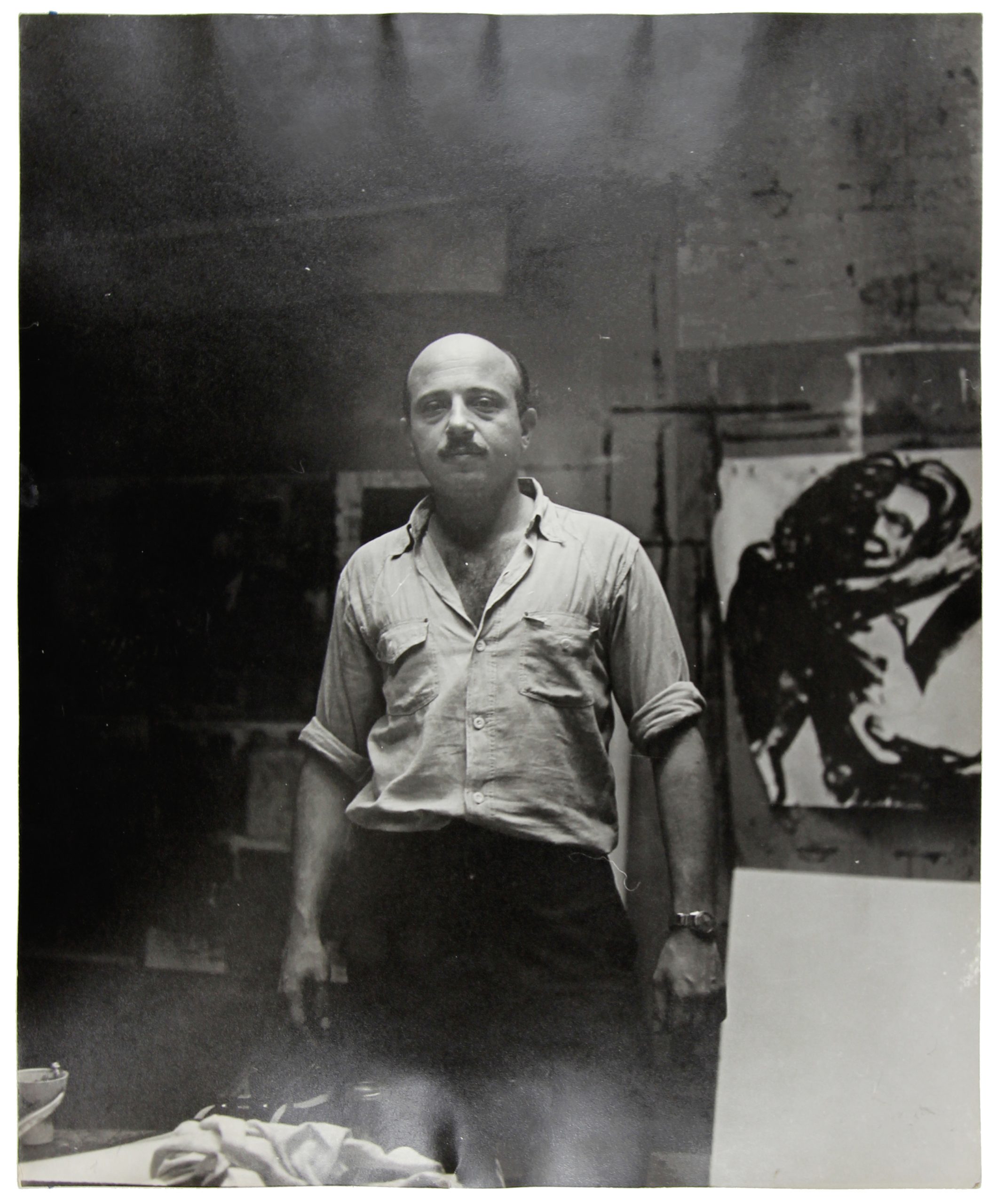

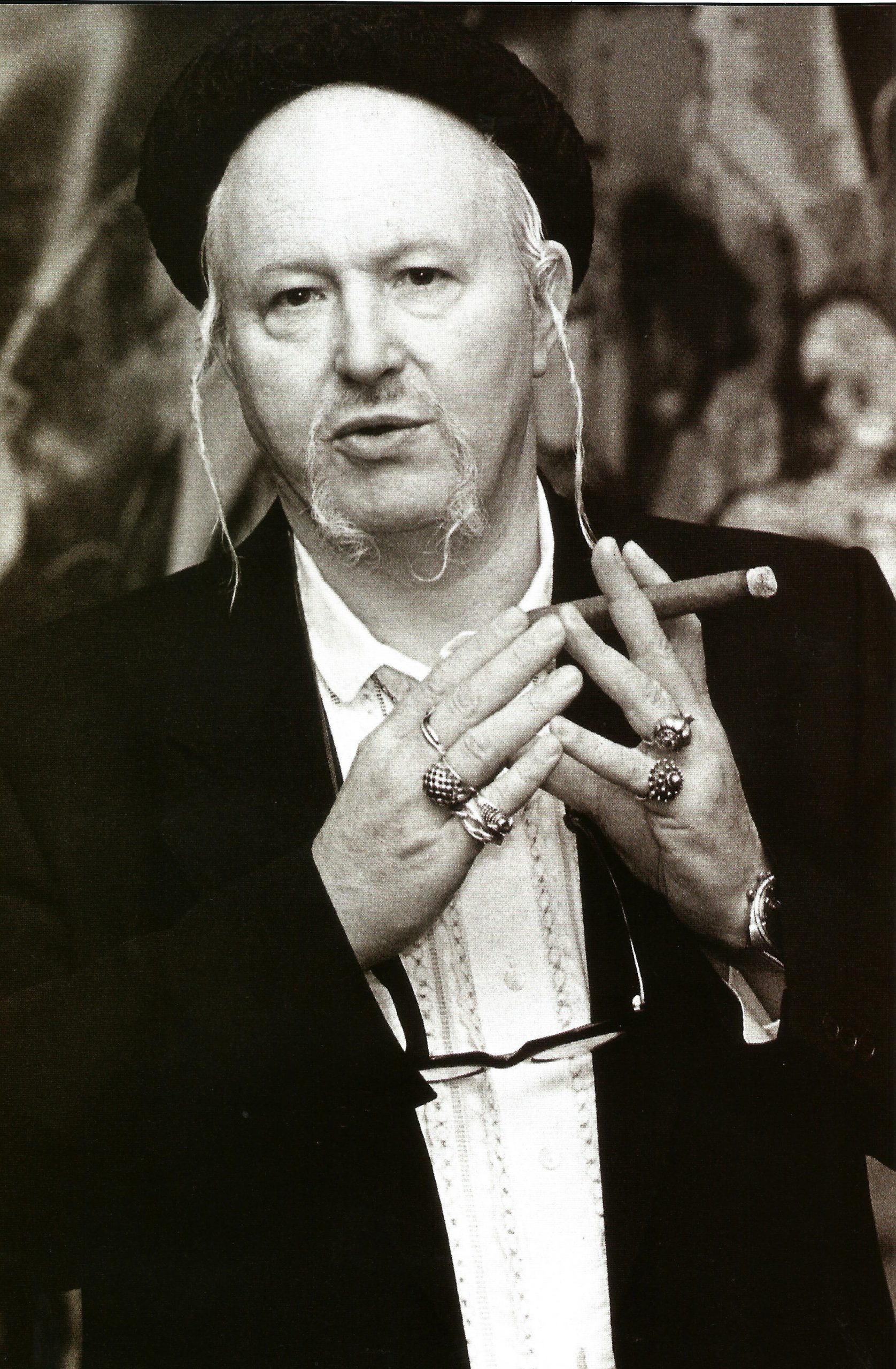

“The art world’s a nest of shit”, says Boris Lurie in Amikam Goldman’s 2007 documentary, NO!art Man. Leading the filmmaker around his cluttered New York studio, the American artist and writer chats about his process, his contemporaries, and life on the fringes of the scene.

Eventually, Lurie lifts a large black-and white portrait from a sea of papers. “This is a photograph of my boyhood girlfriend who was killed”, he says. The girl is Ljuba Treskunova, murdered in Lurie’s native Riga in Latvia by Nazi forces in 1941. In his memoir, Lurie recalls their final moments together: “I am embracing Ljuba in the empty snowy courtyard on Kalnu Street. She kisses me with great warmth… A few days later there is no more Ljuba”.

The photo has been stained beyond recognition by dripping rainwater. Again, no more Ljuba. “Nature did that”, says Lurie, pointing to the leaking hole in his studio roof. He pauses for a moment and then corrects himself: “No, not nature. Actually the fault of the landlord”.

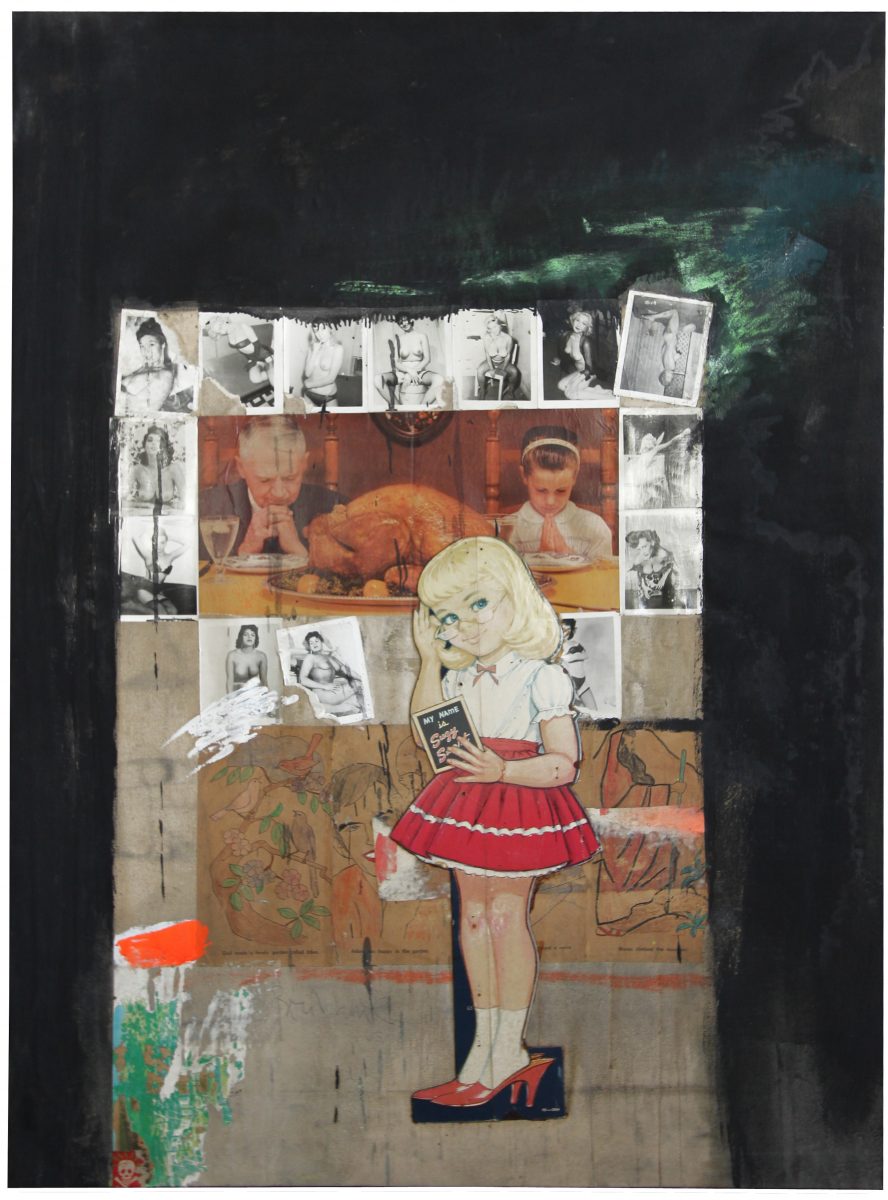

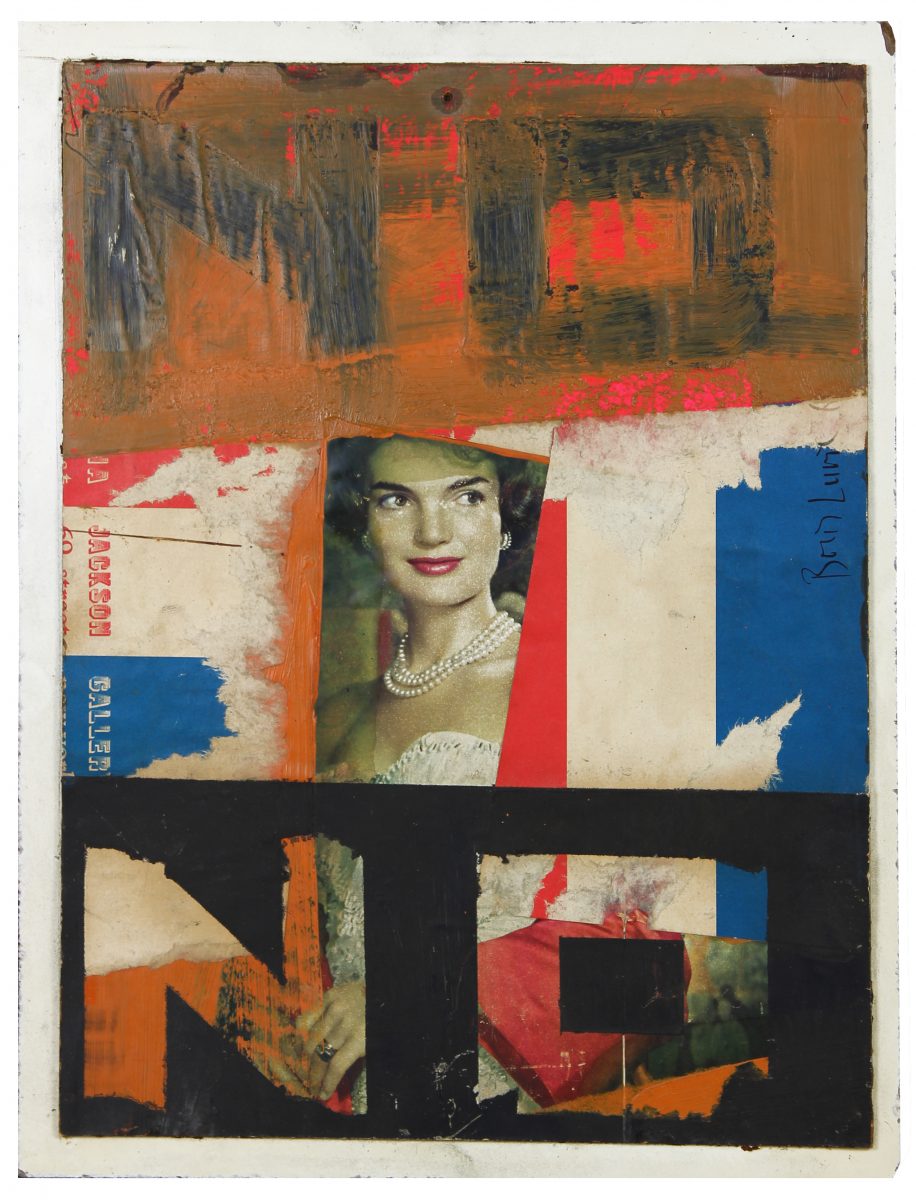

- Left: Boris Lurie, Susan Sweet, 1963; right: NO with Mrs. Kennedy, 1963

In a microcosm, this is Lurie and the NO!art movement’s entire project: castigating not just the historical violence of the Holocaust, but also the ongoing violence done to memory by aspirational capitalism. Lurie wants history to flare up in the face of his viewers. He also wants to hold perpetrators to account, from stingy lower-east side landlords to SS leader Friedrich Jeckeln.

Between November and December, 1941, Nazi forces and collaborators under Friedrich Jeckeln’s command marched nearly 25,000 Jewish women, children, and older men out of the ghettos of Riga and into the Rumbula forest. They ordered them to strip naked in the bitter cold and then shot them all. Lurie lost his mother, grandmother, sister, and Ljuba to this massacre. He and his father were interred in work camps. Through shrewd connections and blind luck, they survived. After the liberation of the Magdeburg camp in 1945, and a brief time living among the American army in Germany, Lurie and his father travelled to New York.

Here, Lurie set about fulfilling his ambition of being an artist, painting the ghetto buildings of Riga from memory, and lurid scenes from work camps in nightmarish hues. He discovered a culture dominated by Pop and Abstract Expressionism, surface-level stuff, responding to the explosion of consumer capital by participating in it, and, worst of all, prudishly unreceptive to his unflinching depictions of suffering. Lurie and his acolytes cried “NO!” The name stuck.

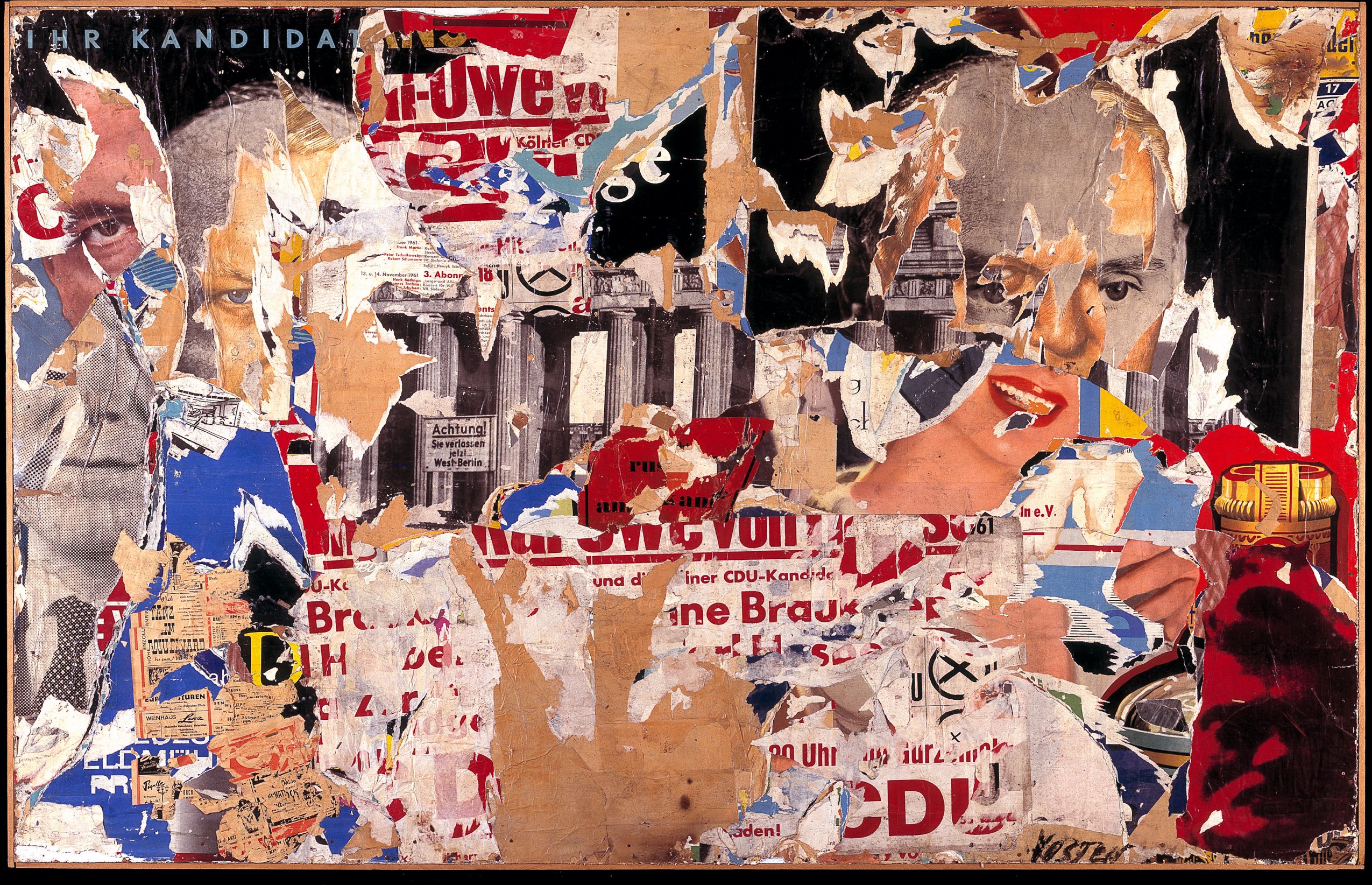

Among these acolytes was the German artist Wolf Vostell, a member of the experimental Fluxus group of artists. Vostell’s interactive ‘happenings’ also attempted to bring the realities of the Shoah into the sanitised art-world. At their best, they deconstructed rarefied space and communicate the real horrors of history; at their worst, they came across like a kind of Secret Cinema of suffering.

“Lurie wants history to flare up in the face of his viewers”

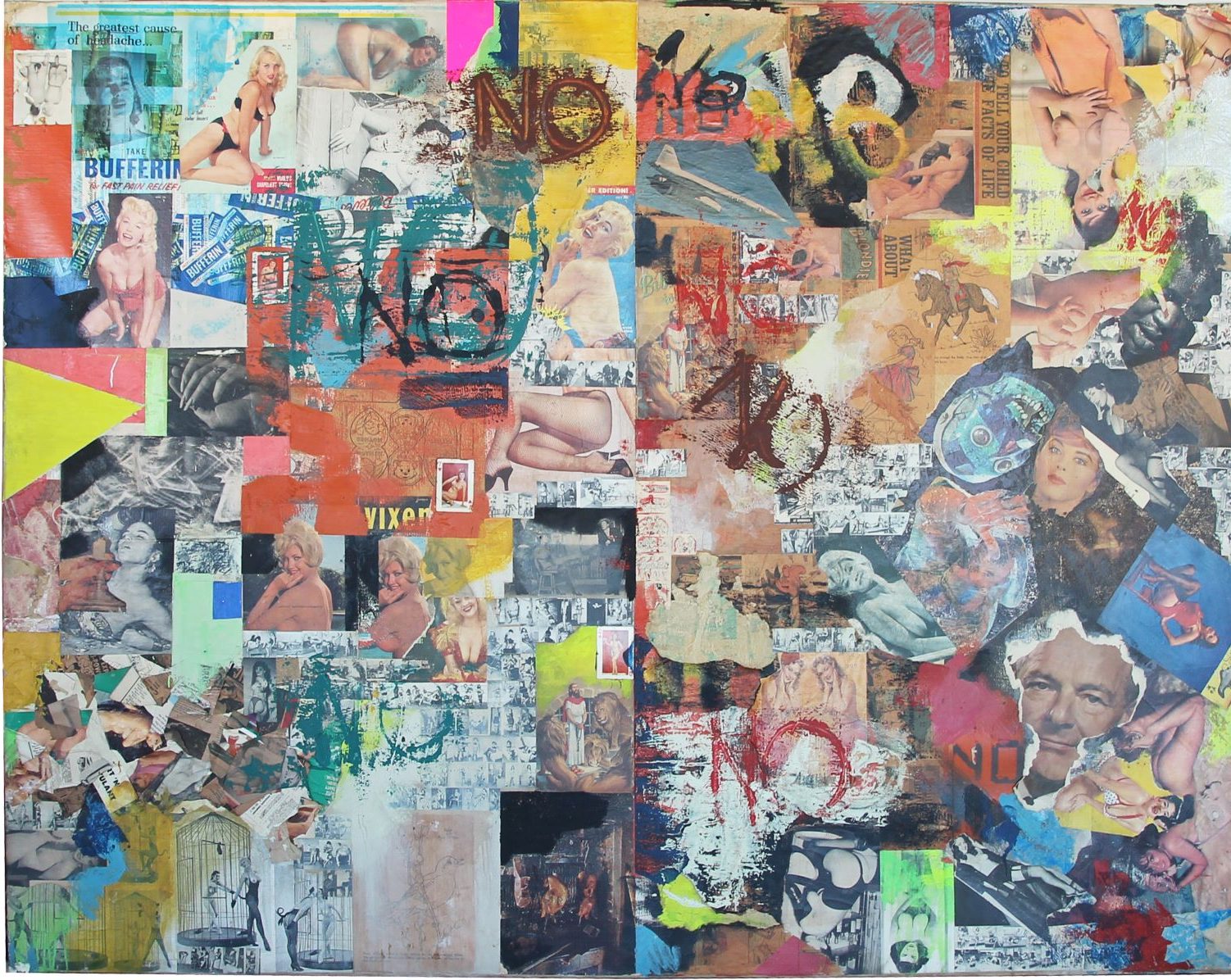

As Vostell began staging participatory mass-graves in paddling pools, Lurie made collages juxtaposing softcore porn with photographs of Holocaust victims piled on transports. An early exhibition at Lurie’s March Gallery was called Doom Show. Another was titled Shit Show, with piles of fake faeces bearing the names of up-town gallery owners.

These artists were determined to make it impossible to reconcile them with the mainstream. And so they have remained, despite flurries of renewed interest in the 1990s and early 2000s. Now, in Art After the Shoah, an exhibition of Lurie and Vostell’s works with this accompanying publication, they’re back.

“Lurie’s conflation of sex and violence made him, at times, a ragingly entitled misogynist”

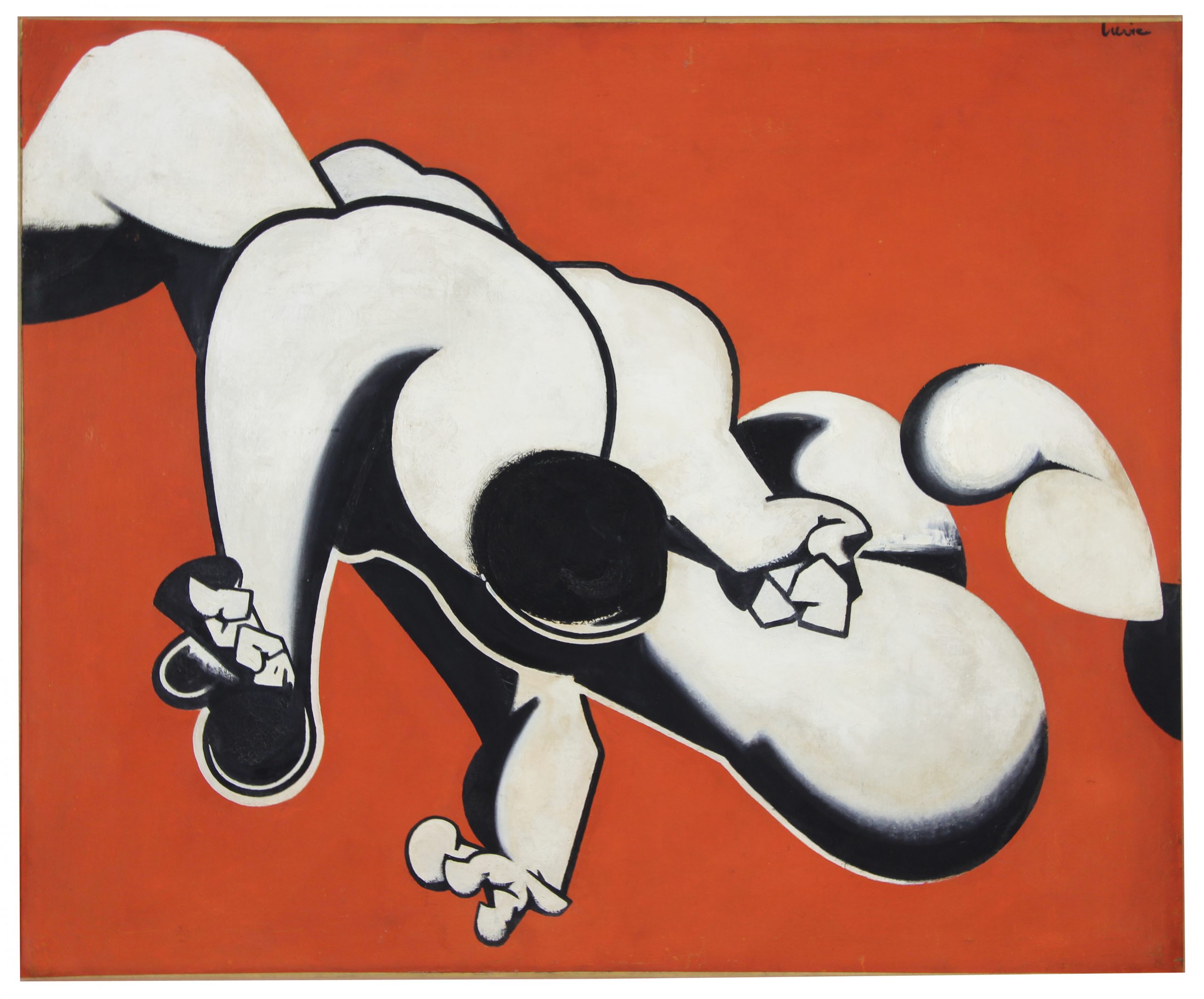

It’s a curious project. At first, you can’t help but feel the sheer force of Lurie’s work in particular. His Dismembered Women paintings (1947 onwards), with their soft curves, their sculptural sense of beauty, their flawless control of colour, and, finally, their repugnantly casual splitting of bodies into separated parts, create a noxious mixture of compulsion and repulsion, fusing sexual desire and morbid curiosity. For Lurie, the chauvinist commodification of women’s bodies in America, the titillation-for-profit image economy, mirrored the gunpoint ‘striptease’ of every woman he had once loved during their final moments in the Latvian snow.

This book, though, eventually does a disservice to Lurie, Vostell, and their potential audience in two related but distinct ways. On the one hand, it softens them for the mainstream. On the other, it overstates their anti-establishment credentials, refusing to critically interrogate their flaws and blind spots.

In Art After the Shoah

, curator and cultural commentator Tom Freudenheim points out that the current drive to rediscover overlooked artists favours those who fit into pre-existing schools (for example, Norman Lewis, Joan Mitchell, and Lee Krasner being retroactively accepted as important Abstract Expressionists). Further, and crucially, such ‘rediscoveries’ overwhelmingly favour apolitical, non-radical artists.

Conversely, Art After the Shoah can be credited with reviving a truly political art of alterity, criticising anti-Semitism, American imperialism, the erasure of history, the shallowness of the art world, and Zionism (in a 1997 letter to Vostell, Lurie says “the Israeli consul is being dogmatic when he sees East Germany as ‘anti-Semitic’, certainly anti-Zionist; but anti-Semitic is not right”).

But elsewhere, the book risks fumbling the rehabilitative bag. For one thing, there are inaccuracies. Eckhart Gillen and Daniel Koep misquote Seymour Krim’s intro to the inaugural NO!art show, describing its intention to “torpedo the eye and rob your soul of its clichés”. The actual 1963 text describes artists that “will torpedo the eye and rape your soul of its clichés. They are a band of rapists in a sense…‘hot’ pop artists out for copulation rather than cool ones doing doodles”.

“The current drive to rediscover overlooked artists favours those who fit into pre-existing schools”

Typo or deliberate, it’s indicative of the book’s ‘cushioning’ effect. Elsewhere, it’s full of art-speak puff, keen to establish continued relevance while not putting people off (with the notable exception of Gillen’s brief, excellent biography of Lurie).

The replacement of ‘rape’ with ‘rob’ also illustrates the book’s lack of interrogation of the artists’ flaws. Though Lurie’s life-long conflation of sex and violence allowed him to skewer Western commodity-fetishes, it also made him, at times, a ragingly entitled misogynist.

His beatification of Ljuba, like Dante’s Beatrice, may itself be considered commodifying and puritanical. And Lurie’s moralising about pin-up girls and sex-workers should be balanced against his memoir’s violent fantasies about German “blondes”, his incel-like dismay at finding American women unwilling to “provide quite normal human satisfactions”, or his friend Jack Micheline’s descriptions of Lurie hiding in sex-club corners obsessively sketching the dancers.

Though it presents us with this evidence (usually buried in footnotes), the volume as a whole does not explore these unpalatable aspects of Lurie’s furious power. A more successful project would make the valid case for Lurie’s revival (there’s hardly been a better time to scream NO!), but also do him the courtesy of tackling his complications. This would tell us something more complete about the ugliness of historical and personal trauma.

Lurie and Vostell responded to an irreconcilable rift in human history by making art that is itself irreconcilable with any present moment. That is both its failure and its power.

Adam Heardman is a poet and writer from Newcastle upon Tyne currently based in East London

Boris Lurie and Wolf Vostell: Art After the Shoah, edited by Daniel Koep and Eckhart Gillen, is out now (Hatje Cantz)