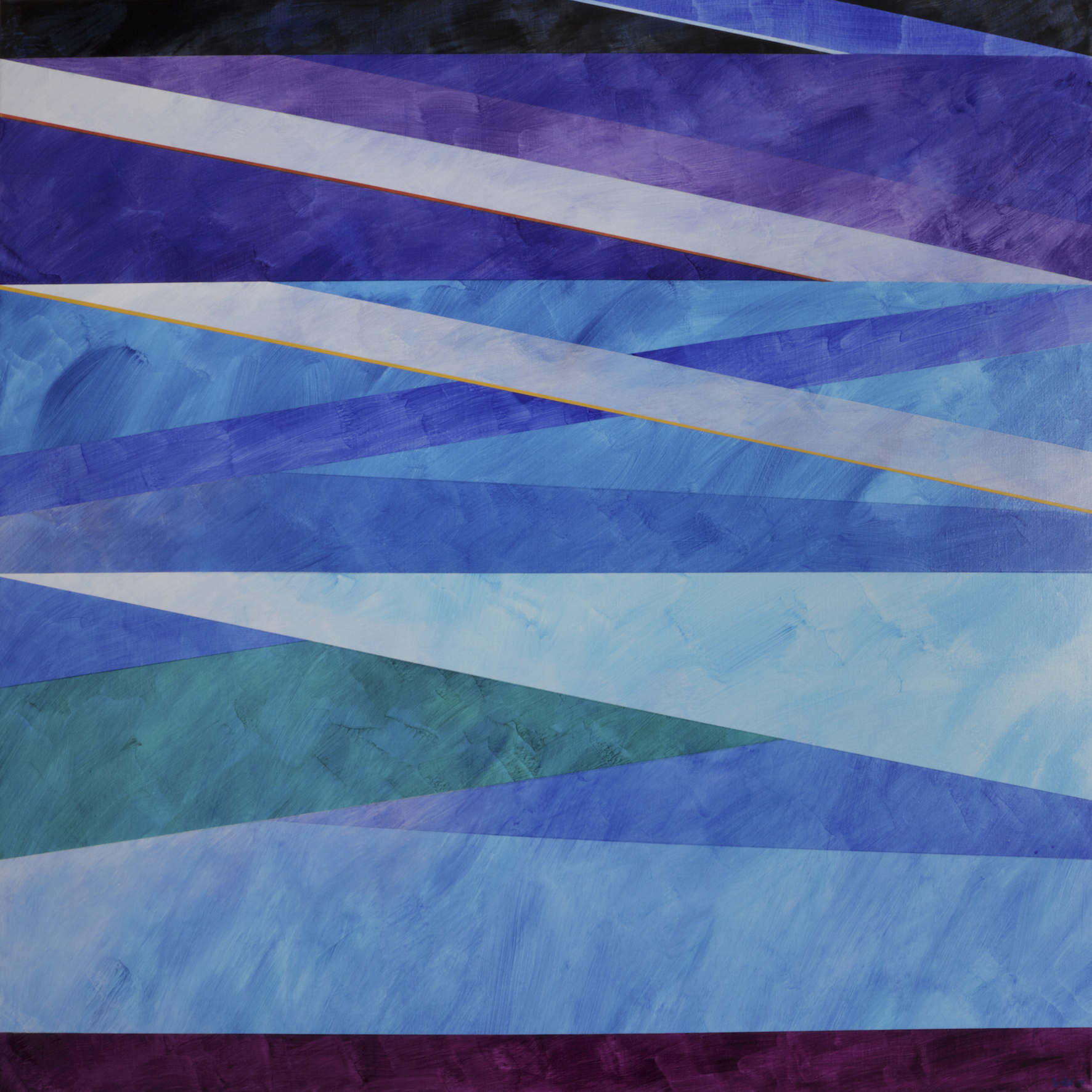

Palestinian artist and art historian Kamal Boullata is somewhat of a master of painting, creating precise yet poetic works that frequently address Palestinian identity and religion. …And There Was Light is his first London solo show since 1978, opening last week at Mayfair’s Berloni.

Can you tell me a little about the work that is showing in …And There Was Light?

When I was given the opportunity to show in this gallery, I looked at the space and I thought of seven paintings that could fill up the walls. From there I thought about God creating the world in seven days. I went back to Genesis and I read about what happened every day in the legend of the creation. Hegel has written some of his greatest works on the creation, this grand subject is as important as the Messiah by Handel, yet I have never really seen anything in painting about the legend of the creation. Out of every verse of those seven days I picked up an idea of colour combinations. I worked on a structure to restrict my geometric compositions and kept on doing variations.

This is your first exhibition since 1978 in London – do you feel your work has changed quite drastically since then?

Oh yes. One grows like a tree. When I look at my work from say 1978 it is like looking at the earliest branches and now it is like looking at the fruit. It keeps changing all the time, without me really knowing. The works in 1978 were mainly works on paper with coloured inks, pen and brush. They were semi-figurative and a little bit abstract, whereas now I move further and further away from figurative painting into abstraction and geometric abstraction.

Have you felt your role as a painter change a great deal since then as well?

I think so. In the last three decades lets say, the vision of art has changed a great deal. But, painting always remains central to the whole language of self-expression I think. We have all kinds of installation, performance, video. These are all different things that have evolved, but painting remans at the centre of it all. Painting is an extension of writing, whether we like it or not, or whether we admit it or not. There is a connection between what the hand does and the mouth and language. This has been there since humans painted in caves.

You write quite extensively about art. Do you feel there is a conflict for you as an artist, or do these seem to fit together within your practice?

Perhaps I am saying what I’m saying because I also write about art. To me the writing and painting itself complete each other like holding something in two hands. If you hold something just in one hand you might not see things as being so balanced. I have to write and paint at the same time, it always was like that.

Are you quite spontaneous when you paint? Do you know exactly what you want beforehand or do you let the work take you in its own direction?

I know what is going to happen and I do a lot of sketches. I only stop doing the sketches when I’m tired, and when I’m tired I know that I should begin doing the painting. The pencil marks, the structure itself is like the skeleton. So the skeleton is the same, the body is the same, but the spirit is different. The colours are like the soul of the painting, the spirit of the painting. In a way when I do the painting it is skeleton and the soul coming together to create the body of the painting.

You are known for the use of light within your work. Is this something that you build in, or is it something that you leave bare that shows through?

There are times when I actually start with very light colours and then I see myself travelling into different layers of transparency where things become darker. There are times when out of the darkness, light comes through. Transparency is one of the major things, I think it’s the most aesthetic part of the visual language and I’m fascinated by transparency and reflection. Transparency builds on something dark into something light. It starts with light in darkness. This is why I also like to live around water. I enjoy the reflection of a building in still water, or in the sea how a reflection breaks up in a different way.

Do you feel there is a moment of completion for you?

Never. I never even like to sign my paintings. I abandon a painting when I’m done with it because I have not been able to go any further. It is a matter of leaving it behind where I know it will have a life of its own with somebody else. For many years I didn’t like to see any of my paintings hanging in my environment. But since I got together with my partner some thirty years ago, she said we have to have this. So I began to learn, only in the last say five to ten years about how I can live with a painting of mine.

Going back to your heritage, have you always felt the influence of Jerusalem on your work?

Yes, to me Jerusalem is always central in my work. Jerusalem has been called the ‘navel of the earth’ and it is a place of resurrections. All these legends about creation, Jerusalem has always been present in my work. Somehow being exiled from Jerusalem gives me also the push to go forward. I feel Jerusalem is not behind me. I have lived in Italy, France the US and now Germany but Jerusalem is still ahead of me, before not behind.

Do you feel your relationship with Jerusalem changes over the years, or is it more of a solid presence?

It becomes more than just the place. It is also time. Jerusalem is a combination of time and place and it has always been like that for endless centuries. But then the older I grow, the more I see that the quality of this marriage between time and place becomes personalised. Why do I have to think of the legend of the creation when I’m living in a place like Berlin? I did not think of it in terms of coming from Jerusalem, but now that you’ve brought it up, I can see that. I am not a religious person at all but I feel there is a spiritual connection to this place that I have never had for any other place that I have lived in.

And finally, do you have any new work planned for the months ahead?

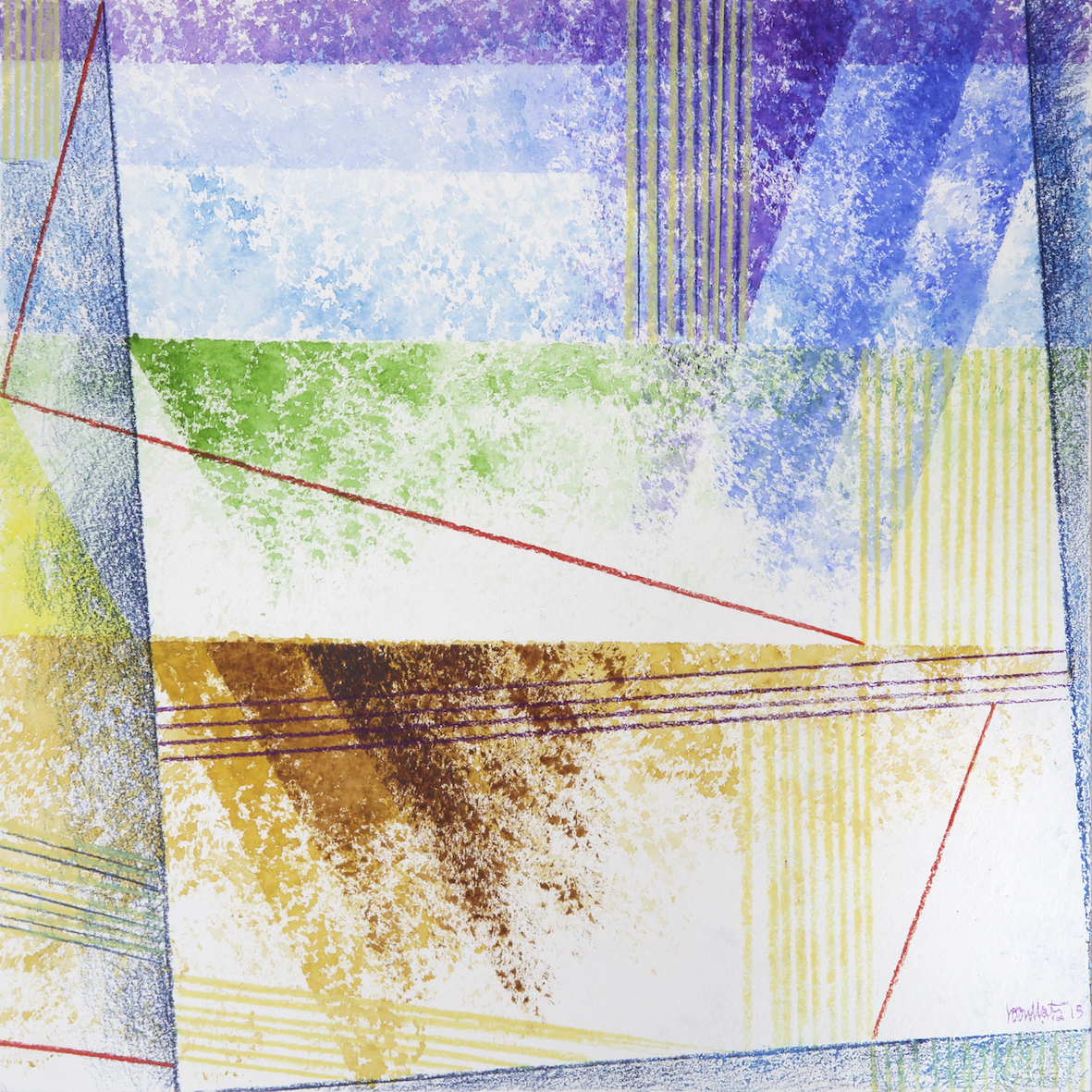

Yes, but now thinking mostly of how I can depart from this exhibition and be able to think of something new. I have to be under a great urge to really begin painting, it is a very daunting job, just like writing. You have to be able to sit for endless hours and do nothing but focus on what you’re doing. Once I’m in it, I’m lost and it is a beautiful feeling, but once I get out of it I feel a great fear to go back. I have all of these ideas, but how can I do them? I lose confidence in whether I am really able to put on a white canvas what I am thinking and feeling. In the case of this exhibit, I started the watercolours to break the fear by playing around, by saying ‘nothing matters, let me do something beautiful’. Once the idea came for the exhibit the fear became larger. The idea has to be almost complete before I can dive into it, it doesn’t happen while I’m doing it. To me it has to be complete as to where I should be going and then it is almost like standing on a cliff and thinking of being on the other side, but there is a whole valley in between. How do you do that? Do you fly there, or walk downhill? But you do know the where you want to go, and then you have to find the way around without falling.

Kamal Boullata …And There Was Light is showing at Berloni until 31 October

Addolcendo, Watercolour, gouache and crayon on paper, 25.5 x 25.5 cm (2015)