When I meet Katharina Grosse on a cloudy London afternoon, the first thing we find ourselves discussing is holidays. The German artist is in town for her solo exhibition at Gagosian, nestled in the semi-industrial backstreets of Kings Cross, and is looking forward to a trip to the English countryside, which she praises with the kind of fervour that surely only a city dweller can summon. She is seeking open landscapes, bracing walks and quiet nights, a far cry from her adopted home of Berlin. As a painter, she is closely attuned to her immediate surroundings, although it is unlikely that she will be undertaking any watercolour studies of flora or fauna on her tour of the great outdoors. Instead, she is known for immense technicolour paintings that can scale to cover entire rooms and even whole buildings, layered with acid-bright acrylic shades sprayed from a paint gun.

“I think that every art work is completely transformed by being looked at”

At the South London Gallery in 2017 she engulfed the Victorian architecture of the exhibition space in riotous colour, which popped defiantly against the stark white of carefully stencilled areas left untouched. The previous year at Rockaway Beach, New York, she turned her attention to a hut destroyed by Hurricane Sandy—at the invitation of MoMA PS1—coating it in great swirls of pink, red and white. Set against the bleak beach landscape, it erupted like an outsized raspberry ripple dessert, surreal, seductive and hyper-saturated. Grosse creates complete environments in which viewers can lose themselves, where there is no defined beginning and end; observation becomes immersion. “I think I always had a very natural feeling that I could expand the image… even as a child I did,” she remembers, talking about the impulse behind her huge-scale works. “I had one piece of paper, then I glued four together so I had a larger field, and I would put it on a wall. Then I realized, ‘Oh, the wall is also a part of it.’ I found out about it very early.”

In her show at Gagosian, Prototypes of Imagination, a draped, rainbow-painted cloth dominates the imposing central space, stretching across more than twenty metres. It both emphasises and veils the surrounding architecture, and is suggestive from certain angles of the type of rolled Colorama paper favoured by photographic and video studios, where perspective expands within the frame to a seemingly infinite vista. Walking into the exhibition in real life, the illusion and the reality are both evident, as if you’ve been let loose amidst a psychedelic stage set. For Grosse, “leaving the canvas was an activity of revolution”, and by scaling up she invites viewers to inhabit an alternative, uncanny world that subverts expectation and makes the ordinary appear alien. This unfamiliar environment was fully evident at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, where she coated giant sheets and piles of dirt with her layers of paint—always in unmixed colours. Moving through it, I felt as if I had arrived at a scene of mystical destruction, where rainbow rubble clustered, and walls appeared to emit a saturated glow. It was an experience that stayed with me long after I had returned home, as if I had made a trip not just to Venice but to the moon.

The immediate feedback of human interaction within these installations is key, as viewers navigate on their own terms. “I think that every art work is completely transformed by being looked at. It’s not just a dead material, it’s being activated by the people who use it and who look at it,” Grosse observes. Following on from this, I ask what frames of reference—beyond painting—she draws upon for this focus on the body. My instinctive guess is that she might look to the performed rhythms of contemporary dance, but she catches me off-guard with her response. “I like how players on a field communicate. There was a moment—it is not so important now—when I was very interested in strategic paradigms of football teams. That this guy knows the ball is going to arrive there; they learn it by heart but there is this really amazing way that they don’t repeat what they’ve done before. I really like those things,” she enthuses. “Or how people move in the street, or how something heavy falls on the ground. All of that is fascinating for me.”

We move to a discussion on television and cinema, both formats that have also been influential to her development. “I did consider filmmaking for a little while. And I grew up in an environment where there was photography taught in the art school when I was student, there was Gerhard Richter who was discussing photography versus painting, and still does… there was Nam June Paik,” she recalls. Born in 1961 in Freiburg, Grosse attended the Düsseldorf Academy of Art in the 1980s. “It was very challenging for a painter. I went back to painting because it’s so direct. For me, very often, things are more inspiring if they come from the realm where the body is very important itself: in the space. When I look at a film there is already such a transformation going on.” Does she enjoy films still? “I love watching films, but they have such a strong impact on me that I sometimes don’t get them out of my head for many days…”

“I like how players on a field communicate. There was a moment—it is not so important now—when I was very interested in strategic paradigms of football teams”

It is a sentiment that reminds me of the experience of immersion in Grosse’s own works. Densely layered, their build-up of paint is emphasized by the white space left behind by the foam stencils that she uses—whether in a large-scale work or a smaller canvas. Cut to blocky, abstract shapes, they mask and filter out her mark-making, revealing entire blank areas once removed. In other instances, these stencils are applied later in the process of painting, leaving shadowy imprints that begin to blend in with the many coats of colour, visible only on second or third look—like an optical illusion that is just beyond your grasp. The stencils reflect the various stages of each work, but ultimately give little away. “You see the layers, the dripping of the paint… something has occurred, as if you had an accident and there was a pool of blood on the trees. You only see the blood, you don’t see the rest, you don’t see the story that led to it,” she says, ominously. Then she laughs. Grosse has a tendency to speak seriously on big concepts, from our understanding of time to authenticity of materials, but she retains the highly likeable ability to suddenly send herself up, taking a step back from the occasional intensity of our conversation.

We relax, sip at the remains of our black coffees and talk about one of the most important elements of her work: the spray gun itself. Why has she made use of it so frequently? “I worked a lot with a paintbrush, I still do, but what you do is you pick it up, you paint, and then it is exhausted and you have to go back to pick more paint up,” she explains, matter-of-factly. “The interesting thing about the spray gun is that there is a large supply of paint; you are not interrupted by the amount that you use. It is like a felt pen.” In photographs of her working, she can be seen dressed in all-white overalls and full face mask—a look that carries more than a strong resemblance to an exterminator. “The lightness and the supposedly easygoing way of doing it camouflages or ironizes the fact that it is quite aggressive,” she says, considering the comparison. “And there is a certain aggression that I understand, painting needs to be visible in our life: I want it to be very present, very in your face, in a sense.”

We relax, sip at the remains of our black coffees and talk about one of the most important elements of her work: the spray gun itself. Why has she made use of it so frequently? “I worked a lot with a paintbrush, I still do, but what you do is you pick it up, you paint, and then it is exhausted and you have to go back to pick more paint up,” she explains, matter-of-factly. “The interesting thing about the spray gun is that there is a large supply of paint; you are not interrupted by the amount that you use. It is like a felt pen.” In photographs of her working, she can be seen dressed in all-white overalls and full face mask—a look that carries more than a strong resemblance to an exterminator. “The lightness and the supposedly easygoing way of doing it camouflages or ironizes the fact that it is quite aggressive,” she says, considering the comparison. “And there is a certain aggression that I understand, painting needs to be visible in our life: I want it to be very present, very in your face, in a sense.”

Most visible of all is the raw colour that freewheels throughout Grosse’s work, breathing newly imagined life into everything from dirt piles to the cavernous walls and ceilings of abandoned buildings. Colour is at once symbolic and abstract, with meanings that can be universal or entirely personal, and I am curious about her relationship to it. “Colour is very interestingly independent from space and from sight. Colour can be anywhere: it can be on a lemon or on a yellow flower. It’s always a yellow, but it’s always different. It has no location, colour,” she says. Like her playful, dynamic paintings, colour has the power to transform perception and build unexpected connections between people and place; as she concludes, “I would say that colour is the icon of possibilities; it opens up the field of possibilities.”

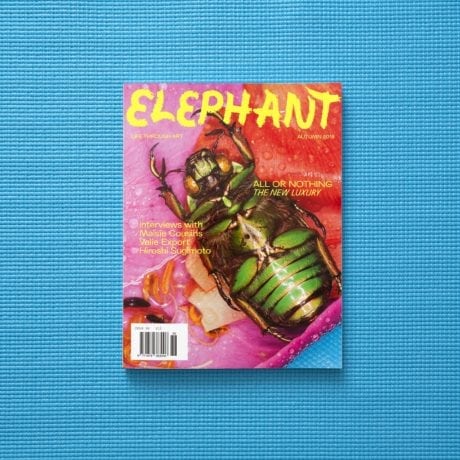

This feature originally appeared in issue 36

BUY ISSUE 36