KAWS has the unique ability to shape-shift between the worlds of fashion, art and design without breaking a sweat and, it would seem, without being pigeonholed. ‘If someone doesn’t accept what I do I can live with that,’ he says, ‘but I don’t think I could live with pretending to be something I’m not.’ Emily Steer finds herself curiously moved by the Brooklyn-based artist’s familiar characters when they are displaced to the Yorkshire landscape.

THIS FEATURE ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN ISSUE 27.

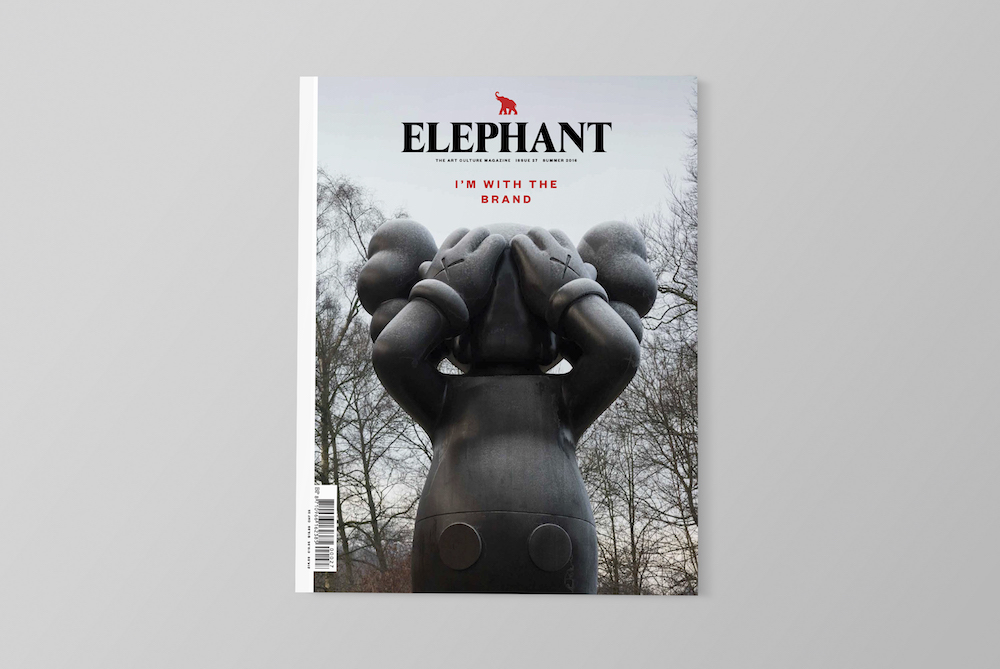

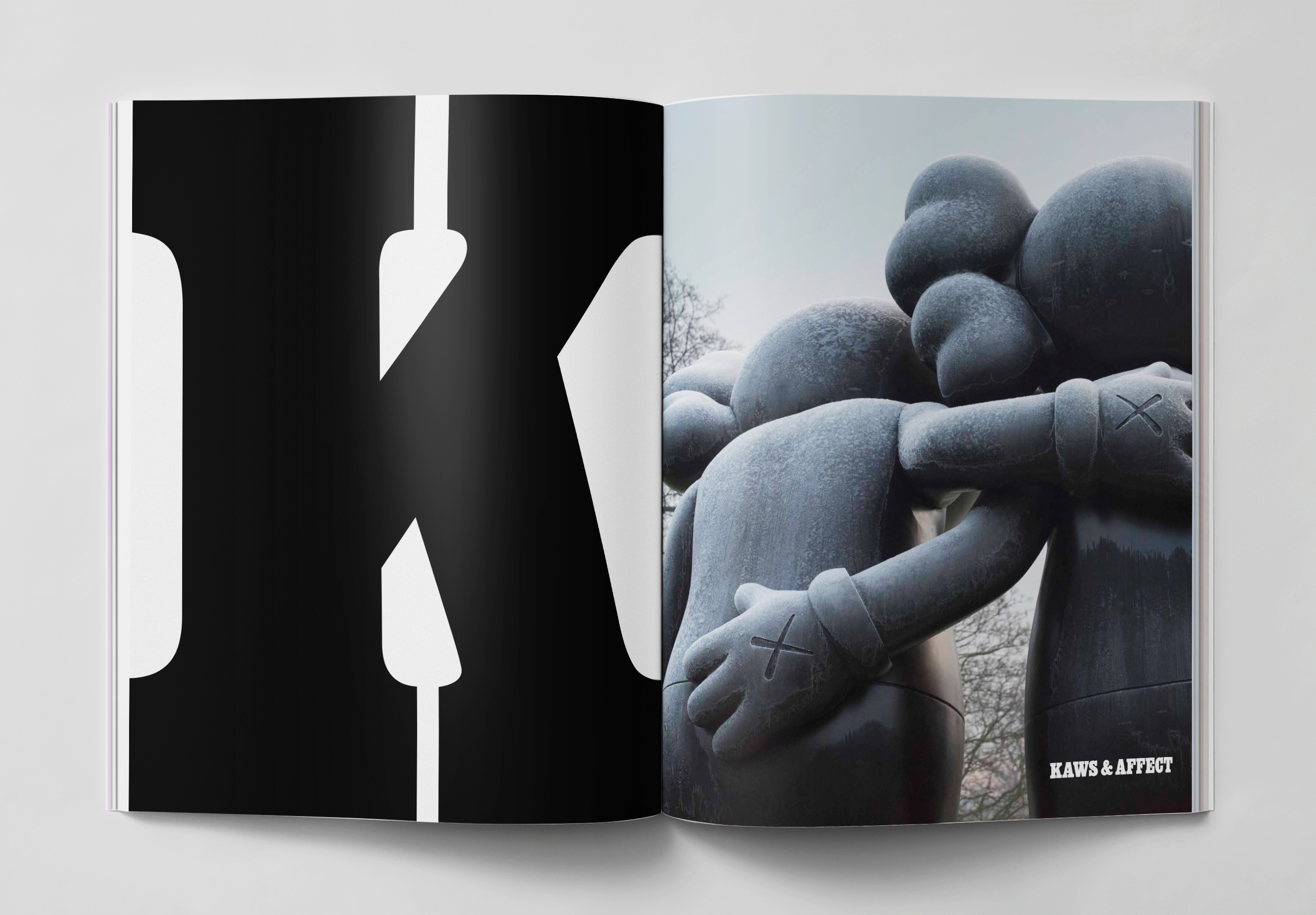

For an artist who slips just as easily onto the fashion pages of i-D and the shelves of Comme des Garçons as the grounds of Frieze London’s Sculpture Park—always high-design, always cool, always, one could easily imagine, more about surface than feeling—KAWS sure can bring on the emotion. Standing among his eight looming sculptures—ranging between 1.5 and 5.5 metres in height, mostly his instantly recognizable COMPANION and CHUM characters—in Yorkshire Sculpture Park’s Longside Gallery for the opening of his first UK museum exhibition earlier this year, I found myself suffering a wave of empathy that I had, up to this point, always considered totally un KAWS-like. The sculptures seem desolate, sad, alone; the larger they get, the more hopeless they appear.

As the Brooklyn-based artist—real name Brian Donnelly—comes over for a chat, I share this sentiment. I had no idea, I tell him, quite how dark these works would feel as a group. ‘Really?’ he questions, with an air of total surprise and, perhaps, indignation. ‘I’m not sure about that. But,’ he follows with a laugh, ‘I guess I’m annoyed when people tell me that they’re cute too.’ Funnily enough, after we speak I find myself in YSP’s fields—hosting six large COMPANIONs; some hunched over as if in shame, others pigeon-toed, hands clasped to faces, horribly reminiscent of Pinocchio’s Pleasure Island boys— still wondering how on earth this couldn’t be seen as dark, when a group of three older ladies walk past and comment on how adorable they are. KAWS, it seems, eludes easy definition.When, in our follow-up correspondence, I ask the artist if it’s fair to say that there’s an inherent loneliness to the work, I get a vague ‘Ha, perhaps’ by way of response.

If he is a little cagey about emotional readings into his work, he is far more open in his relationship with his fans, followers, supporters and shoppers—there are many ways to get involved—and is very much in charge of this relationship, largely via social media and his online presence. ‘The internet has changed a lot of things,’ he tells me. ‘I first started my website in 2002 where I would sell the toys, prints and other products I made. I sold these out of my apartment and would ship all over the world, sometimes getting letters back from people who ordered. I realized at that point how important it was to have a direct relationship with the people who followed my work. Now something like Instagram has become an accelerated version of that, where I can put information about what I’m up to into the world in a very casual way, as well as get an insight into some of the people and things I’m interested in.’With a current count of 444,000 followers, he easily trumps his fellow Instagram aficionado Jeff Koons’s 132,000. He also appears to be genuinely open with his followers, often sharing fans’ photos of his work, replying to comments and posting shots of his young daughter hanging out with various CHUMs and COMPANIONs—and in one case catching up on Sotheby’s magazine.

I wonder how much of the artist himself is given away in his work. As he has progressed in life, his figures often follow a similar route, appearing many times with small children since the artist became a father. ‘I try to be honest with the work I make and personal aspects of my life must find their way into it,’ he says, ‘[but] the feelings I have are probably no different than the feelings that many people have.’ Indeed, much of the universality of KAWS’s work depends on the responses that we all have to the well-known characters that he appropriates—from the Simpsons to Mickey Mouse and Pinocchio. ‘I like the way that they exist as objects and stories in both high and low culture,’ he tells me, in a mirror of his own practice. ‘I think at this point I’m also interested in them as forms and finding ways to create new narratives that have to do with my present life.’

Of course, this sense of self-led identity is helpful for an ‘artist slash’—at various times: slash designer, slash toy maker, slash collaborator with many a famous musician (notably Kanye West and close friend Pharrell Williams) and fashion house (most recently Uniqlo)—to develop an image that isn’t so locked into one thing. When I ask if he ever felt a temptation to follow one path, so as not to be shut out by any of the worlds that he dips into—the art world especially isn’t too known for its love of slashies—he responds firmly in the negative. ‘It’s important for me to follow my own interests,’ he tells me. ‘I like moving around and learning new things in different fields. It keeps it interesting and one thing usually informs the other. If someone doesn’t accept what I do I can live with that, but I don’t think I could live with pretending to be something I’m not.’

Similarly, he refuses to be drawn into conclusive conversations about his relationship with brands. I note that there seems to be a contradiction at play in some of his work with the brands he appears to mock—childhood brands like Disney seeming to be emptied out in his work, left as dark husks—and those he works alongside. ‘My only goal in doing collaborations with different brands is to keep things fun and interesting for myself,’ he claims. ‘I enjoy the process of collaboration.’

You could imagine that it is this lack of self-justification that allows the brand of KAWS (‘I try to avoid labels of any kind,’ he says when I ask whether he sees his alter ego as a brand in itself) to be seen, as it is, in so many different lights. Without the artist explaining his every morph, his every different hat, it can be left up to each industry to slap its own labels on. When displayed at Frieze London’s Sculpture Park—Small Lie (2013) was shown in 2014—or an institution such as YSP he can be described in conceptual tones and aligned with the colossi of Pop Art; for brand launches he can be the creative maverick; for musician collabs he can be the New York scenester.

Although much of his wide appeal derives from his pursuits outside visual art, his first creative move was as a graffiti artist, in his home-town of Jersey City. ‘It didn’t seem like making a living as an artist was an option when I was growing up,’ he tells me, ‘but slowly I realized I didn’t want to do anything else and I had to figure it out. I was always attracted to creative people. I grew up around a lot of characters and I think I liked the fact that you can make something from nothing and there is no price you can pay to be creative. This influenced me a lot as I was figuring out who I was as a young adult. I’m influenced as much by people in other fields as I am visual artists. I’ve always learned a lot by just accepting and observing people.’

His first notable forays into art were his billboard interventions in the early nineties. By night he would steal posters from bus stops and phone booths, add his own graphics in acrylic and replace them. ‘I haven’t done “street art” since around 2002,’ he says, ‘[but] I can appreciate the enthusiasm many people have for putting art on the street. What first got me interested was how out of place it seemed. The combination of my work with those advertising campaigns seemed strange. I started painting over billboard advertisements in 1993, it was pre-social media and very few people really knew what they were looking at. Eventually I became bored with it and my interests shifted into other directions.’ It was the creation of a toy in 1999 with the Japanese Harajuku company Bounty Hunter that kickstarted the artist’s ongoing characters—now selling for around $128,000 at auction. ‘When I made my first toy COMPANION I had no plans to make a second,’ he considers. ‘I continued because they remain interesting to me, they give me a good outlet for putting thoughts into the world.’

The price tag for these toys is perhaps best justified—alongside KAWS’s cultural sway—by his ongoing dedication to quality. His love of flawless surfaces is best appreciated when viewing his most mammoth works up close and en masse, such as the newly made Good Intentions (2015) which was made shinily perfect for its first outing at YSP, the intricate grain of wood and detail of the curves providing an optical treat that moves between art and high-end design.

Although he takes charge of the initial design stage, kaws has a regular number of specialists to carry out the later stages, and the entire process combines a mix of hands-on craft and digital programming. ‘After a few rounds of adjustments and once I have a final model, usually between ten and 16 inches tall, I decide what material I would like to make the final work in,’ he tells me. ‘Then the small work is digitized and I can begin working with whatever foundry could best execute the chosen material—often bronze, wood or fibre-glass. I usually don’t know exactly what I’m look- ing for when I start out; it’s a process of finding what feels right along the way. I do know how something should look and feel when it’s finished and I continually push to find that place during the process.’

It is the push for refinement—the apparent ‘factory finish’ that has actually taken a ton of manpower and skill—that has seen him aligned many times with his Popster peers, Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami. As with Koons, there is a sense that KAWS is hunting for feats of craftsmanship, which for all their brashness are very enjoyable as objects. This is an element to the work that becomes much more apparent in person. There are surface decisions made with each piece that belie their actual material— bronze and fibreglass painted matt to look like plastic, wood made shiny to appear as though it’s a man-made wood substitute.To see his works sitting comfortably alongside the weighty Henry Moores in the adjoining YSP fields certainly gives a sense of awe for KAWS the visual artist.

Asked in retrospect what he discovered in seeing his sculptures in the unusually picturesque British countryside, the artist’s answer is expectedly noncommittal: ‘I appreciate all my travel experiences and as I’m writing I’m thinking how I would really like to be back in Yorkshire. It’s always interesting for me to see my work in new settings, I can’t pinpoint what exactly comes from it but I usually end up wanting to make some new work.’

The KAWS exhibition at Yorkshire Sculpture Park continues until 12 June; www.ysp.co.uk. KAWS open-air pieces will show until December 2016