“As a systemized negation of the other, colonialism forces the colonized to constantly ask the question: Who am I in reality?” the voice of actress CCH Pounder booms across American artist Kehinde Wiley’s three-channel video installation Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools), part of his exhibition In Search of the Miraculous at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London. She’s reading from Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, while Wiley’s intimate lens studies the profile of a young black man submerged in the Caribbean sea. His knowing expression and reddened eyes are flooded with light; his skin glistens, just like in Wiley’s celebrated oil portraits.

While Pounder switches her source material to Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization, Wiley’s camera does something unprecedented, panning out to the landscape. It follows boats as they leave the harbour, traces the silhouettes of sailors as they rush to secure their cargo against the oncoming storm, and marvels upon the tropical hues of mangroves stretching into the translucent ocean. This is a new perspective for Wiley, who is known to train his painterly gaze on the body.

“The film was conceived around the paintings, and the paintings around the film,” Wiley shared during a discussion about his new body of work with the writer, filmmaker and theorist Kodwo Eshun at the BFI last week. Nestled within Stephen Friedman’s second space just across the street, Wiley’s newest paintings—nine in total—mark a significant departure from his previous work, and his last solo show with the gallery in 2013. Leaping into the landscape of the western maritime genre—from the Northern Renaissance to American Romanticism—Wiley reimagines these scenes with black subjects. It’s a powerful move that disrupts the heteronormative gaze of the western canon and on the black body.

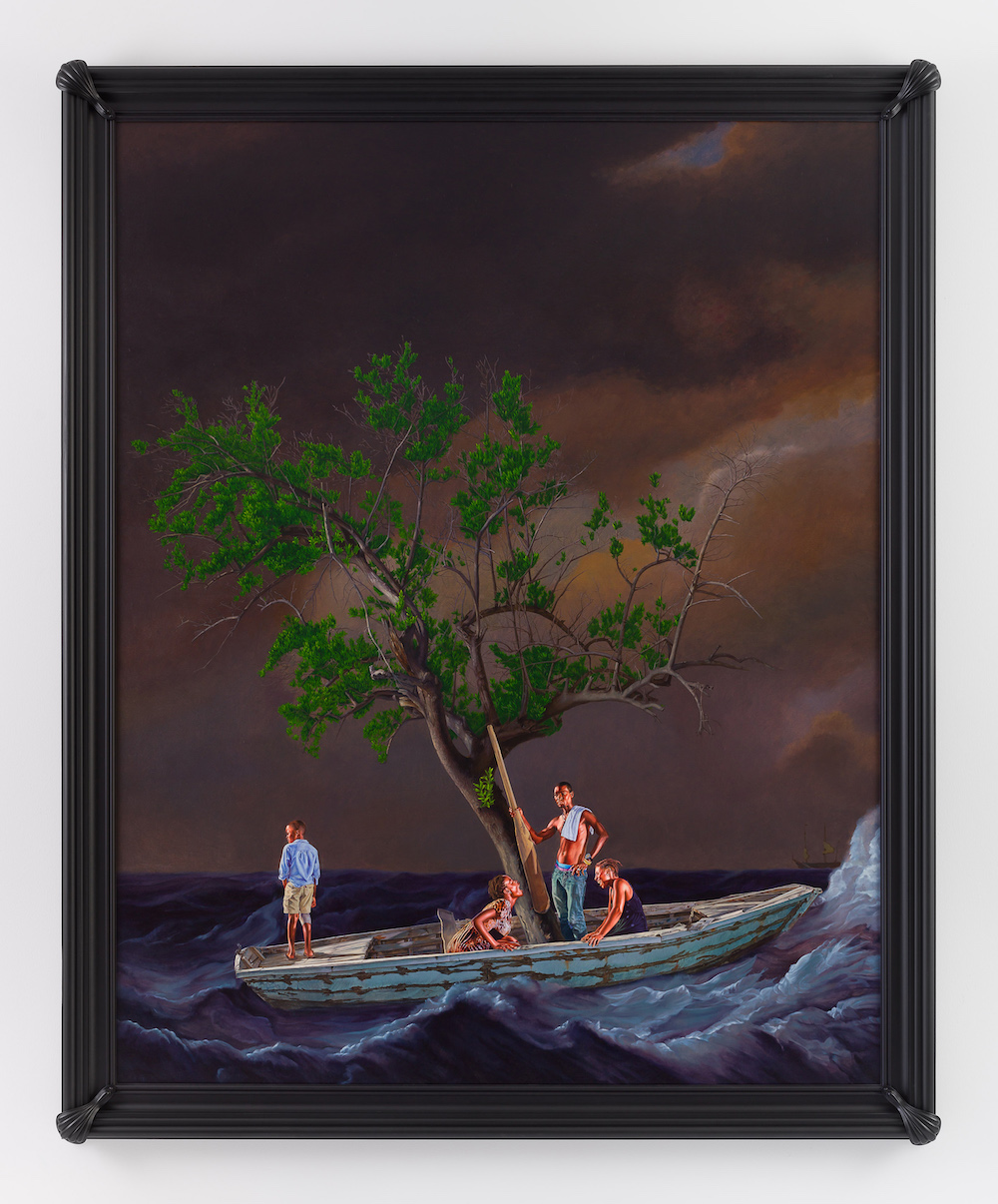

Wiley nails this subversion by pulling as freely from the tradition of master painters including Hieronymus Bosch, JMW Turner and Winslow Homer as the real, lived narratives of the paintings’ subjects. A closer look reveals Wiley’s sea-farers are the same non-actor locals that appear in his on-site film. This symbiotic space between film and painting deepens Wiley’s skill as a painter, a skill with which he replicates with apparent ease Bosch’s teetering Ship of Fools, his figures mimicking the bizarre postures of the monk and nun, or the precarious position of Homer’s fisherman in The Fog Warning.

“The paintings inhabit a surreal and ecstatic alter-reality, a trans-historical narrative that reclaims the tragic and traumatic narrative of colonialism.”

Wiley’s ability to replicate the masters is uncontestable, so it’s more interesting to focus on the aspects of the source that he chooses to modify or leave out of the picture entirely. Take, for instance, the prehistorically-sized fish weighing down Homer’s original halibut fisherman: a mixed message of opportunity tinged with greed, the ultimate prize that might just kill the fisherman who has stayed out too long to make that miraculous catch. Wiley’s subject has no seafaring gear, just a glimmering wristwatch, ring and necklace along with several armbands, and certainly no such prize, but his thoughts are elsewhere. While Homer’s subject casts a nervous look over his shoulder at the swiftly disappearing mother ship, Wiley’s sailor looks outward, above and beyond the viewer: he’s seen something off screen that radiates with almost drinkable light. It electrifies his body in a nearly saint-like glow; it’s a different sort of miracle entirely. Despite the ever-hinging mystery of this centuries-old narrative, Wiley floods the painting with a different meaning.

Moving through the gallery and these subtle shifts with big conceptual leaps—between the original source material and Wiley’s practice—continue to happen. Keeping in mind his earlier portraits—consistently vivid and joyful, with brilliantly patterned backdrops—the aesthetic transition and the impact of its political message is breathtaking. These paintings brood with a darkness that can be credited in part to the drama of the genre which is dialled up exponentially, and the peril of seafaring takes on a racial politics through Wiley’s Afro-Caribbean subjects: a move that draws a parallel with Steve McQueen’s 2002 Carib’s Leap. Here, as in McQueen’s work, the complicated and traumatic relationship of the black body with Fanon’s “dark mass” of the ocean is teased out over and over again in Wiley’s radiating treatment of black flesh and seascape light.

“For Wiley, simply being a black body on open seas is precarious enough.”

By dipping into Foucault’s study on madness and colonization, the ecstatic fate of pilgrimage boats—whose hope, whose cost?—and of madmen in search of reason, Wiley also draws a parallel between the psychological trauma of the colonial subject and the deep-rooted western association of the ocean with insanity, social rejection and alienation. In Ship of Fools (2017), Wiley pulls from the Bosch masterpiece of the same name, even having his models assume the same posture. Again, as in his fishless boat, Wiley’s reinterpretation leaves out the object responsible for the subject’s uncertain fate—in Bosch’s original, a festive pancake that dangles from the mast. The monk and nun are each going at it; the danger of an uncertain voyage sedated or caused by pleasure. For Wiley, simply being a black body on open seas is precarious enough.

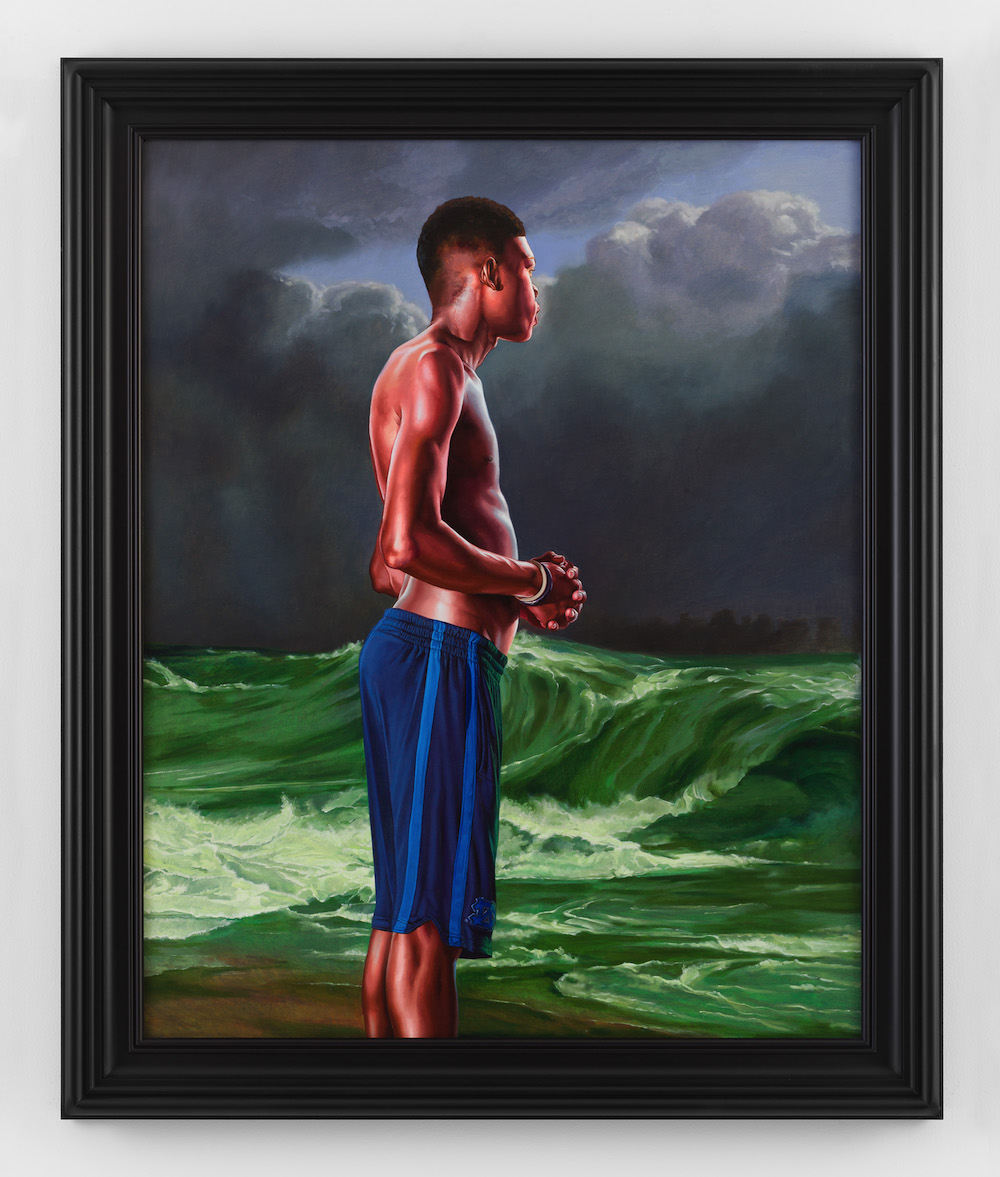

Adjacent to this is a trio of portraits that orbit closer to Wiley’s old world in their focus on the body. They’re vaguely reminiscent of Rineke Dijkstra’s Beach Portraits (1992–2002) series, that depict, in a similar co-opting of the traditional western canon, swimwear-clad teens with unfortunate tan lines, greasy skin and wild hair, uncertain of how to carry themselves—yet celebrated in the glam aesthetics of the classical portrait genre. In Dijkstra’s Dutch world, her subjects are also predominantly white. By contrast, Wiley elevates the adolescent black body to this same status in the canon; he also rejects the gaze of the viewer to which Dijkstra’s subjects are so deferent. Here, lanky bodies in college basketball shorts and tight pink swim shorts gaze out to sea; like the subject in Wiley’s reinterpreted Homer, these teens see far beyond what we can. They’re bathed in that same light of off-screen potential.

With so many references afloat, it’s impossible to pinpoint Wiley’s newest body of work within a single genre. Together, the paintings inhabit a surreal and ecstatic alter-reality, a trans-historical narrative that reclaims the tragedy and trauma of colonialism. Here, underneath the glow of that seascape light, is a space of political potential: a sort of afro-futurism with sea legs. Like the painter himself, Wiley’s subjects have taken a bold leap into uncertain territory, and the future practically glows.

Kehinde Wiley: In Search Of The Miraculous, until 27 January 2018 at Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

You can read more about Kehinde Wiley in Elizabeth Fullerton’s issue 33 interview with the artist

BUY ISSUE 33