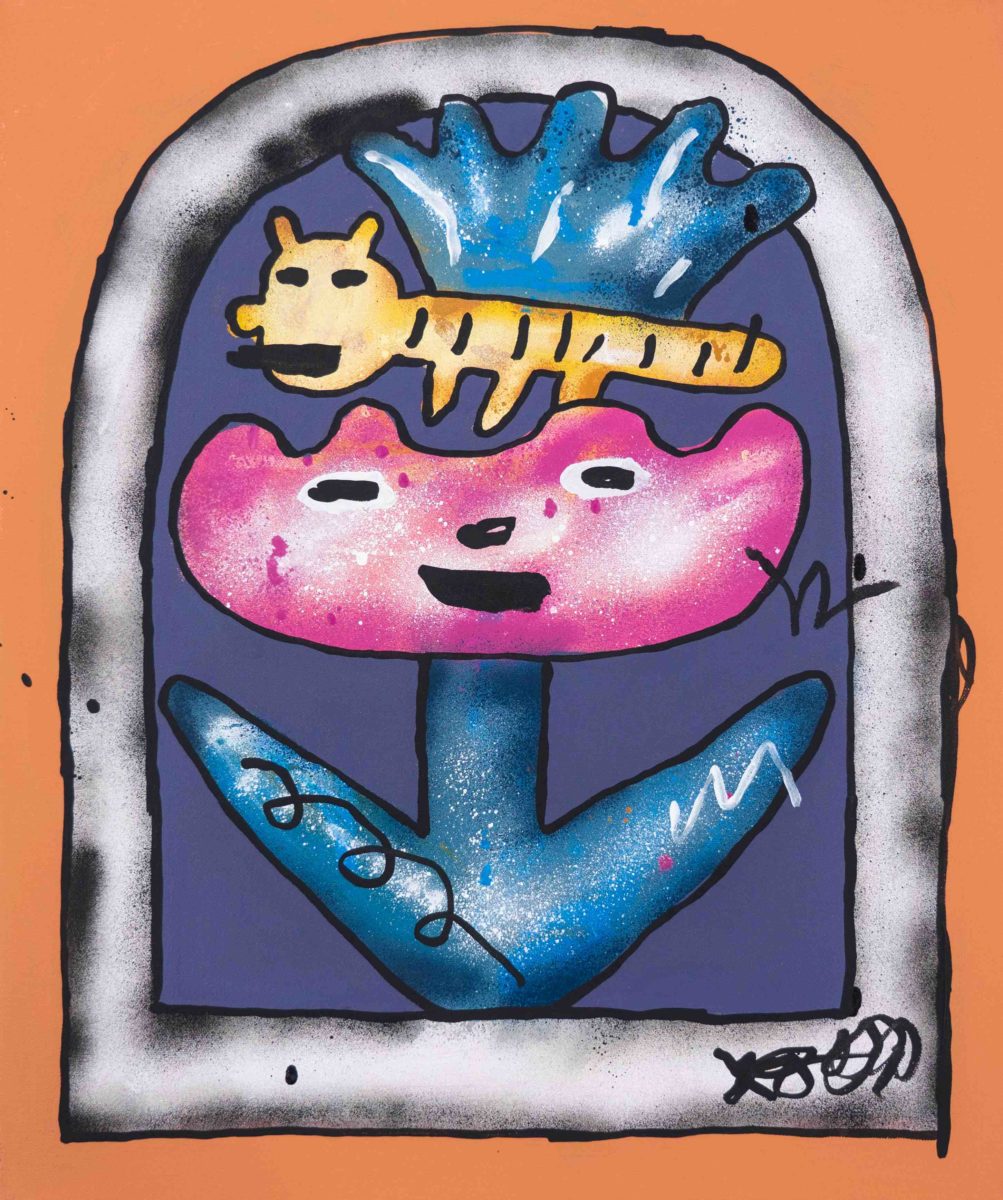

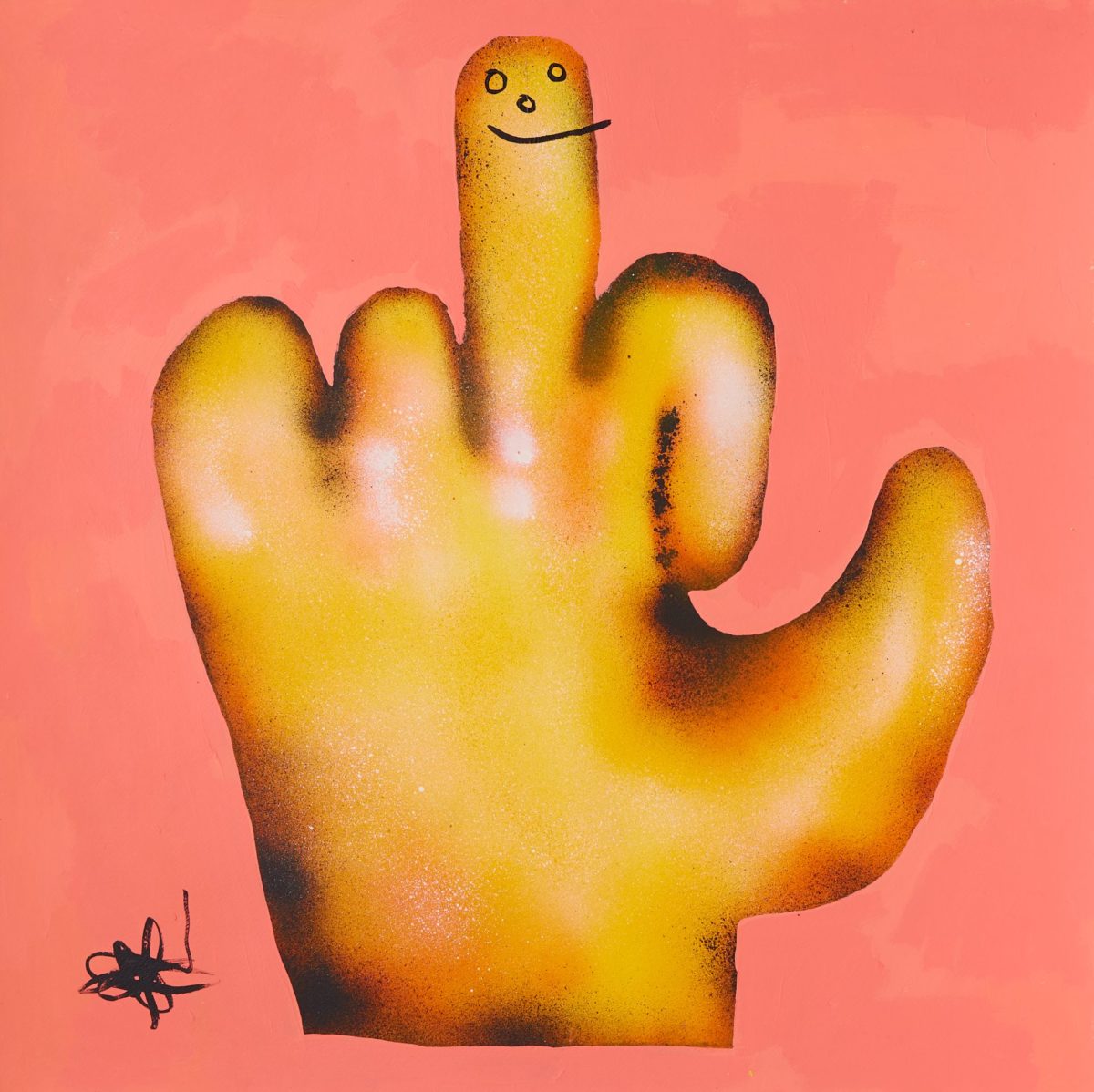

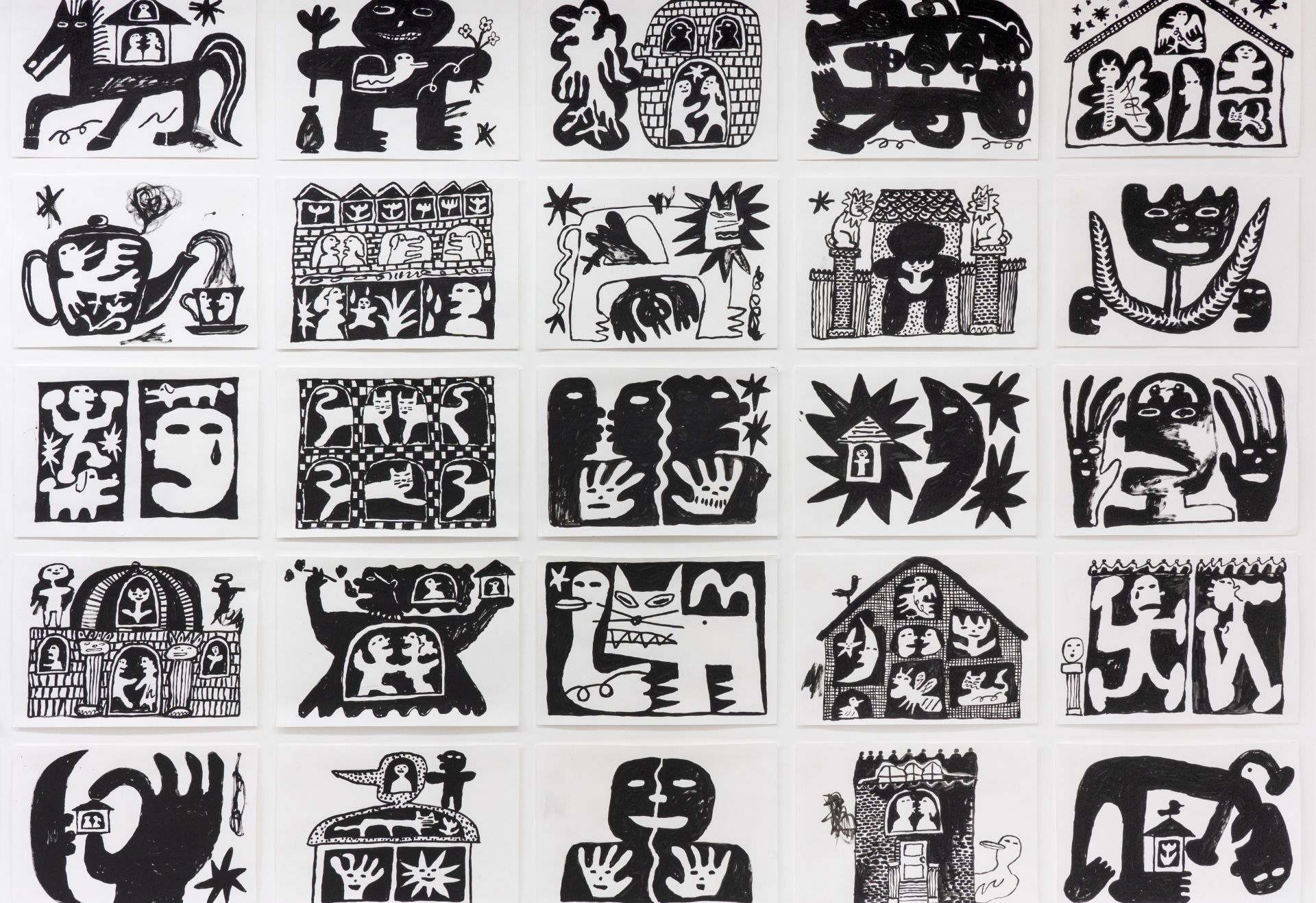

At first glance, Kentaro Okawara’s work is joyfully playful—childlike and innocent, wrought in bright colours, simple shapes and an abundance of cute animals (cats, birds, dogs and more all make up his gloriously stage assembly cast).

On closer inspection, however, more “adult” things are revealed: there’s a hell of a lot of genitals here, albeit ones that often bear smily faces. In short, dick pics, but cute ones. A current show at East London’s Public Gallery entitled Hold Tight displays around one hundred of Okawara’s pieces ranging from small black and white works to brightly hued larger acrylic and spray paint pieces. What’s nuts about all this is that all the works were created in just a month, as the artist, who’s based in Tokyo, took up residence in a space near the gallery. This meant that often, as Public Gallery director Harry Dougall explains, the artist worked through the night, either not sleeping, or bedding down on the studio floor.

Okawara’s work spans many mediums—paintings, sculptures, digital Photoshop works and his bilingual children’s books publisher, PooPoo Books. “I always enjoyed experimenting with a variety of media and never felt pressure to just focus on one,” he says. “I feel they all feed in to my practice: I consider Photoshop just as much of an art material as paint, and when I make books, I like to lay everything out on a computer like a collage.”

As for why he wanted to create books aimed at kids, the idea was to merge elements of Japanese traditional folktale picture books and to bring about more chances for children to read stories in the playful, image-led way in which Okawara likes to tell them.

I spoke with the artist about love, the importance of universally comprehensible art and the joy of finding inspiration in the everyday.

Your work, as you’ve discussed, is quite childlike—were you creative as a child yourself?

Yes, I’ve always had a passion for making things since I was a child and originally I wanted to be a carpenter. My grandmother and grandfather have always been into drawing. When I was between five and eight years old, my grandmother and I would send each other picture postcards almost every day. I still have a large stack of them at home. I see some of the same motifs I use now; or the beginnings of them. When I said that I wanted to be an artist, my family was initially anxious, but they understood as I talked about why I wanted to do it and are a big support for me. My grandmother especially appreciated my art.

Although I was enrolled at an art university in Tokyo, it did not have a painting course, and I was allowed to freely create works in an illustration course. I saw a lot of art books, learned about a lot of great artists, and this freedom allowed me to find my own individual expression.

It’s said that your work investigates the theme of love through symmetry—can you tell me more about what that means?

I’ve always been interested in symmetry, and that is visually evident in the way a lot of my shows have been curated. For this show I looked at symmetry to demonstrate love and the connection between people and things, as the title indicates to hold someone tight.

“There is no perfection—no perfect love—but we still search for it”

While I was in London I saw the symmetries in old decorations and buildings—they were rarely perfectly symmetrical and that seems interesting, because they always look different in certain places. I felt this reflected people’s emotions and lives as there is no perfection—no perfect love—but we still search for it.

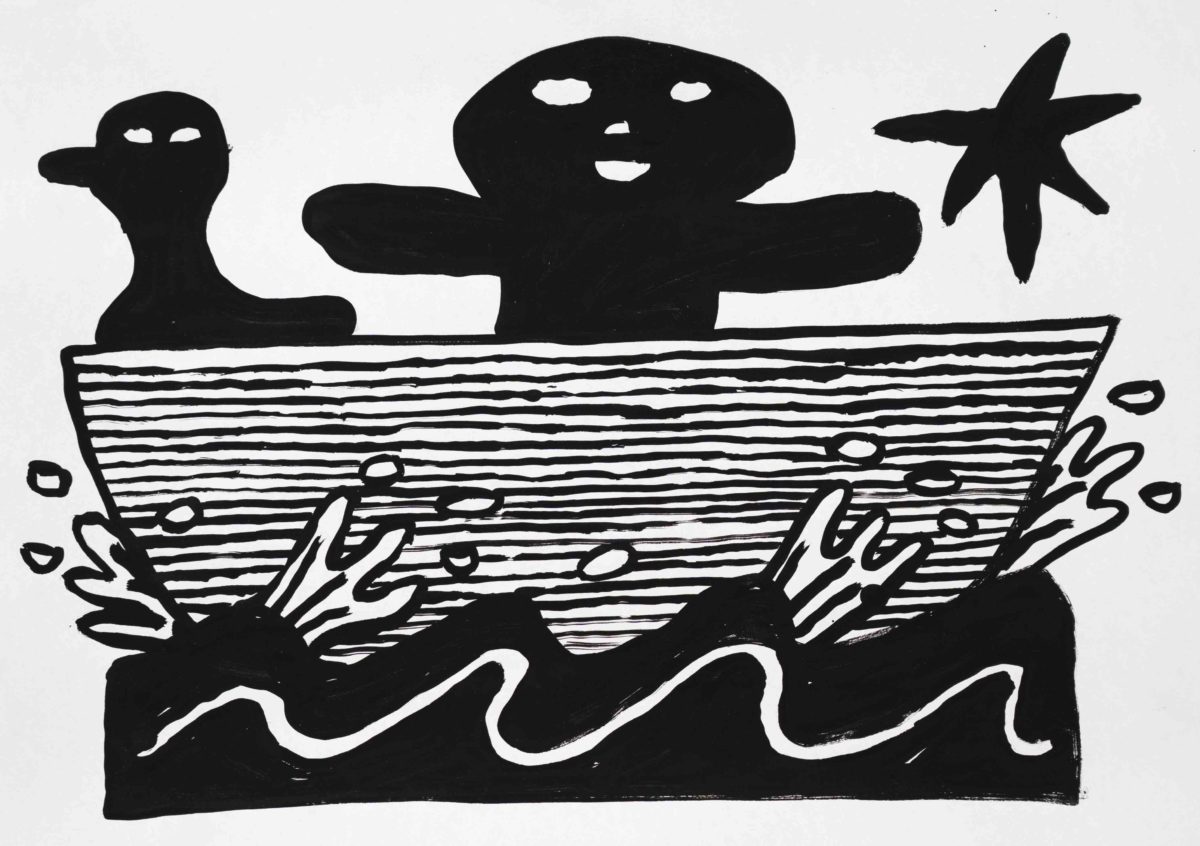

- Kentaro Okawara, Untitled, 2018. Courtesy Public Gallery

You also talk about how your work aims to encourage people to connect with each other, and address the importance of face-to-face communication. What is it about your images that do that?

I want to create a space and a world that can be shared across cultures and generations. When I was growing up, I began to realize that everyone has a different way of seeing and experiencing the world. I began to see that even though the world is big and complex, it is also very intertwined. It all comes down to the simplest and most important level, which is connecting with people.

“I find small things in life that make me happy, like seeing a dog barking, the way a child walks down the street, a person laughing or a friend’s expression”

So, the most important thing when making a work is to draw a motif that everyone can understand. When making a show, I want to show it in various styles to reflect the diversity and complexity of people and to express the importance of accepting, but always have an element of universality to it.

You’ve said you hope that everything you create “makes my mood feel good and makes others feel good”. How does it make you feel better—the creation of the work itself? Or the realization of the final image?

I think that the work is a part of myself, and I think that it is my greatest communication. I find small things in life that make me happy, like seeing a dog barking, the way a child walks down the street, a person laughing or a friend’s expression. I want to remember the feelings I get and make them into sketches. These sketches don’t always make it into my paintings, but the feelings and ideas often become the foundation of my paintings where the motifs are more symbolic. Making the work and sharing my joyful feelings, emotions and experiences makes me feel better; and hopefully does the same to anyone who sees it.

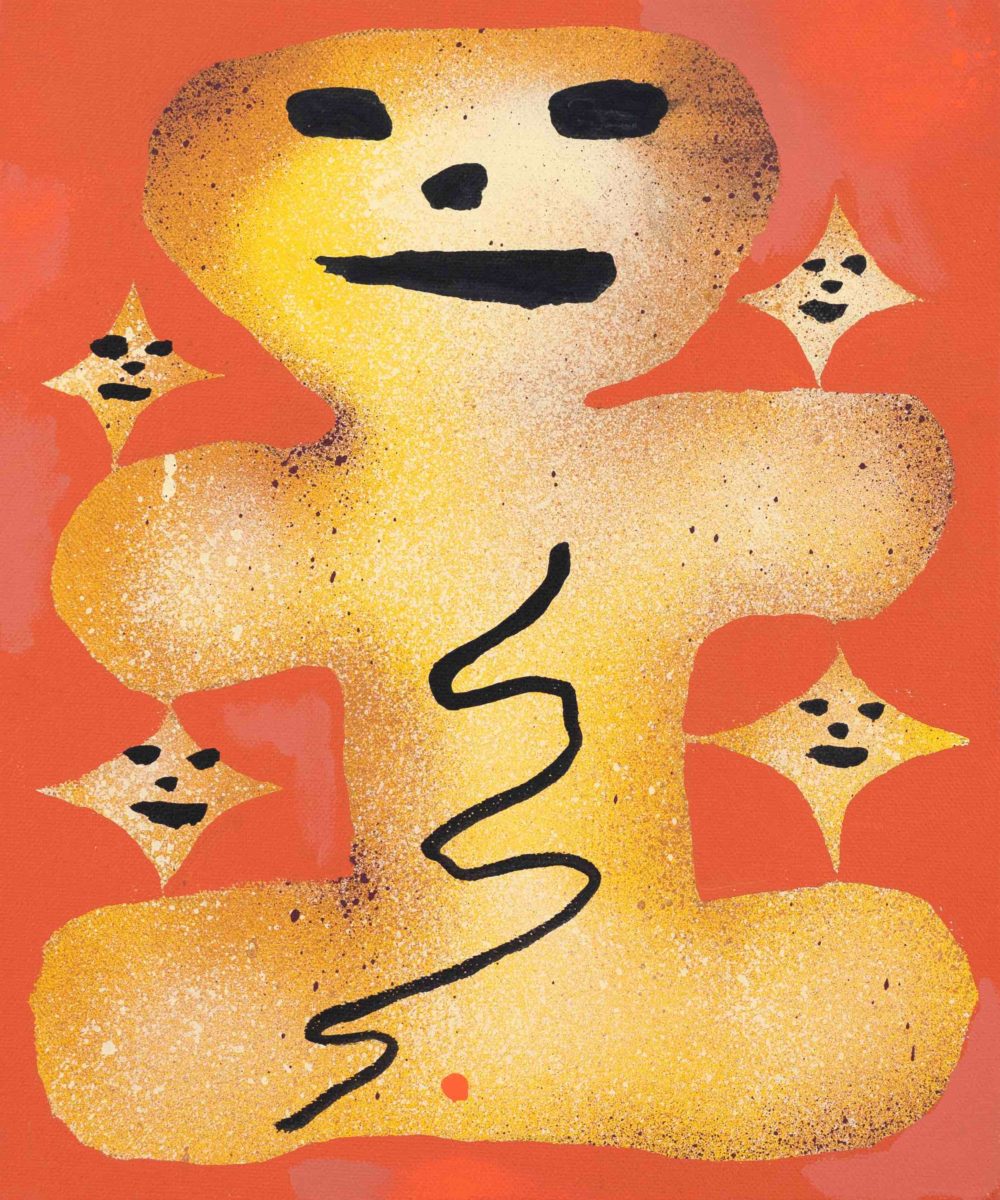

- Kentaro Okawara, Untitled, 2018. Courtesy Public Gallery

What sort of love is your work about? And where do all the animals come into this?

It’s a love of life. As a child I loved making art for my grandma and I still love to make art for family and friends—and everyone now. She showed me that making art is an expression of love. When I hear “love”, I feel like it’s this grand incredible thing, but what I want to express is more of a record of changes in positive emotions that arise from my experiences, things like minor pleasures and the movements of my mind. For example, a child may be stroking a dog or watching a moment when a bee stops in a flower: these acts make me happy.

“I’m not blindly optimistic, as life is interesting because it is complicated and difficult, but without love we have nothing”

The words “I love you” seem to be used lightly in the world now, but I feel that in Japan they have a very heavy meaning. Even though we all know that we cannot do anything without love; we’ve all had many experiences of it blinding us or being hidden. That’s why I find it very important to share the love I feel. I’m not blindly optimistic, as life is interesting because it is complicated and difficult, but without love we have nothing.

The motifs I draw are all signs of emotion. For example, a bird is free, a cat is cute and bewitching… But the meanings are just my own emotions at that time, and it’s not necessarily important to share the exact meaning with others. I think that it’s very important that each individual has different experiences, different emotions and different ways of being captured [by the work]. Ultimately, I don’t think that communication can be done with words.

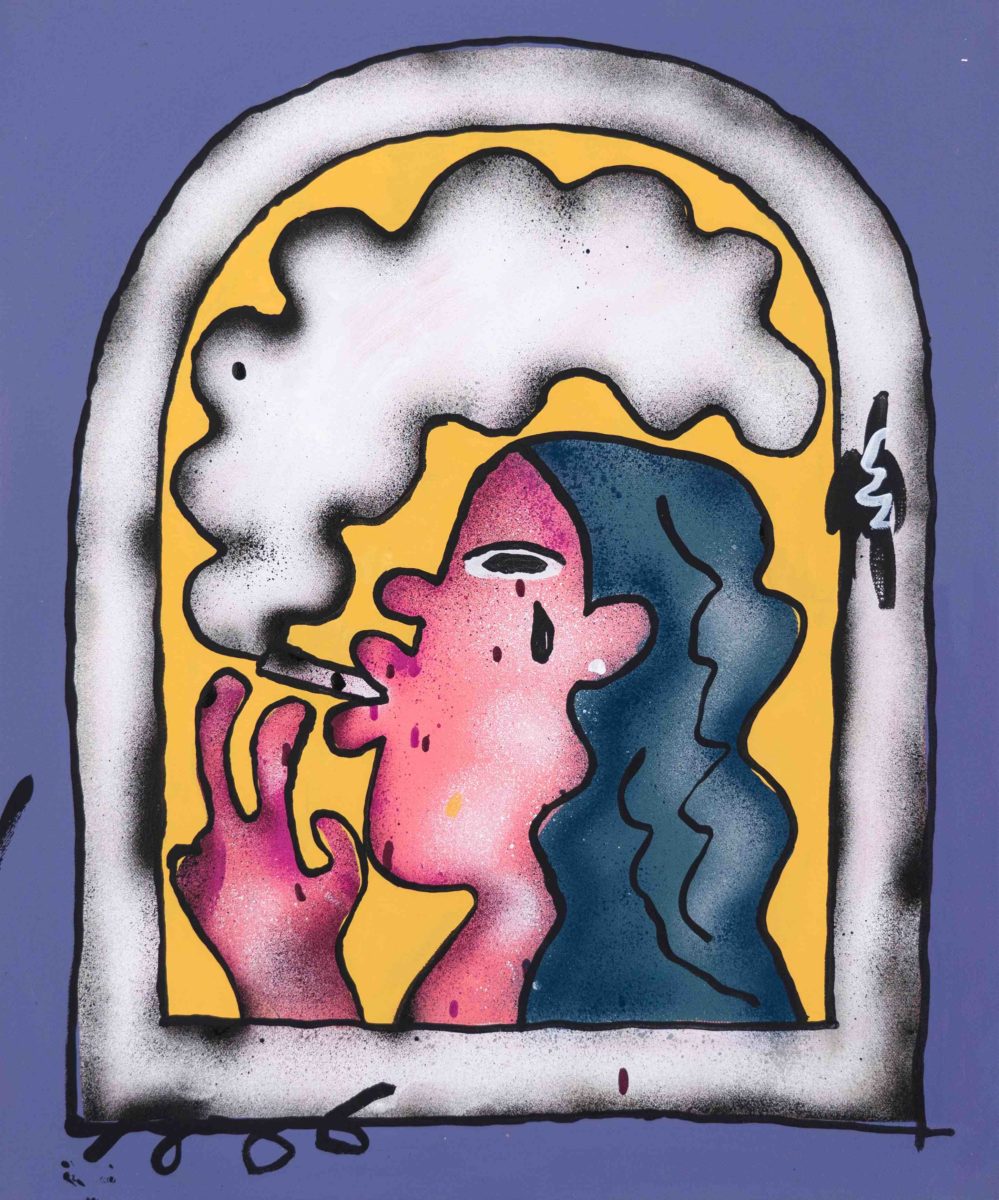

- Kentaro Okawara, Untitled, 2018. Courtesy Public Gallery