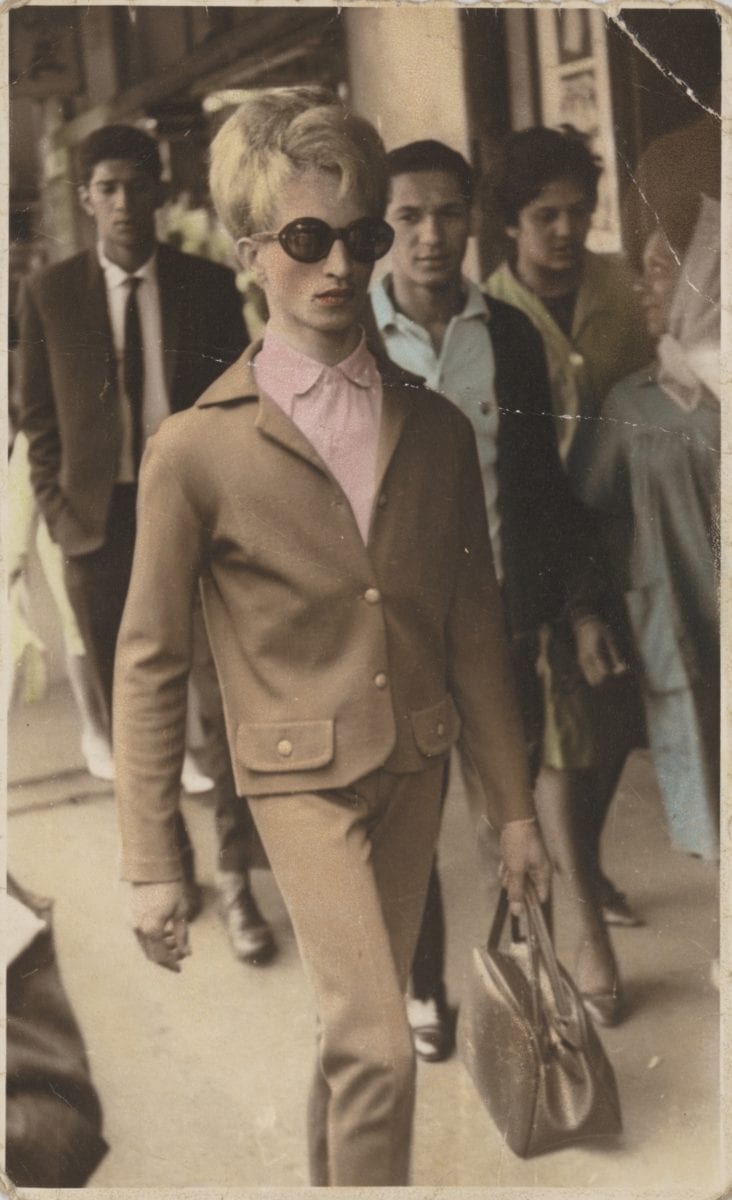

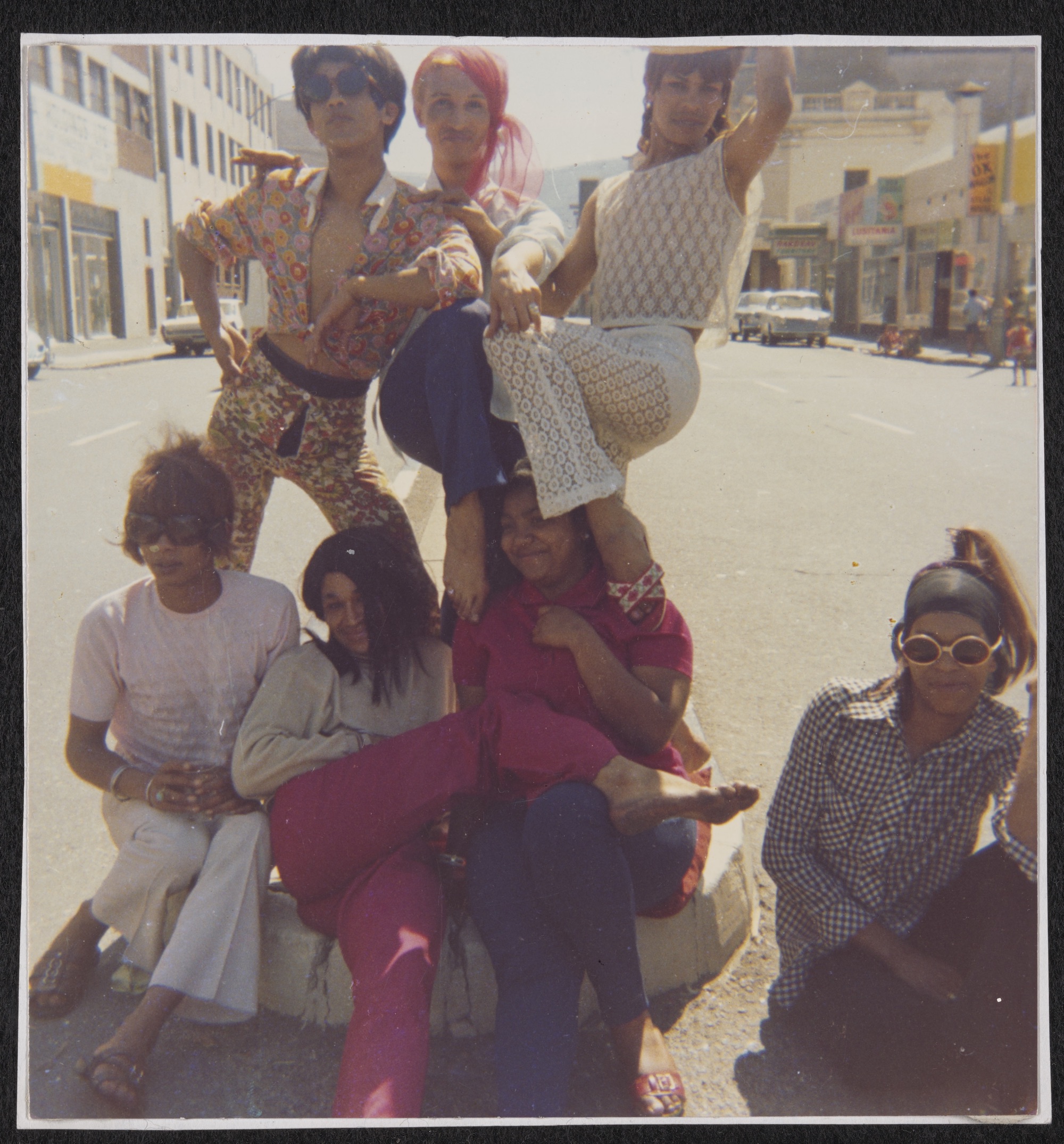

Seven womxn face the camera, four of them sitting, the rest standing. Olivia, Kewpie, Patti, Sue Thompson, Brigitte, Gaya and Mitzy. They are uninhibited and exude a sense of ease, playfulness and freedom. This image is taken in the middle of Sir Lowry Road in Cape Town. Pink pants, pink hair, oversized sunglasses: the image is choreographed and the womxn are not caught off guard.

These are the Daughters of District Six; always glamorous and always beautiful. This particular image is one of over seven hundred images that were donated by Kewpie to GALA Archives (Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action) in 1997; it would come to be known as the Kewpie Project.

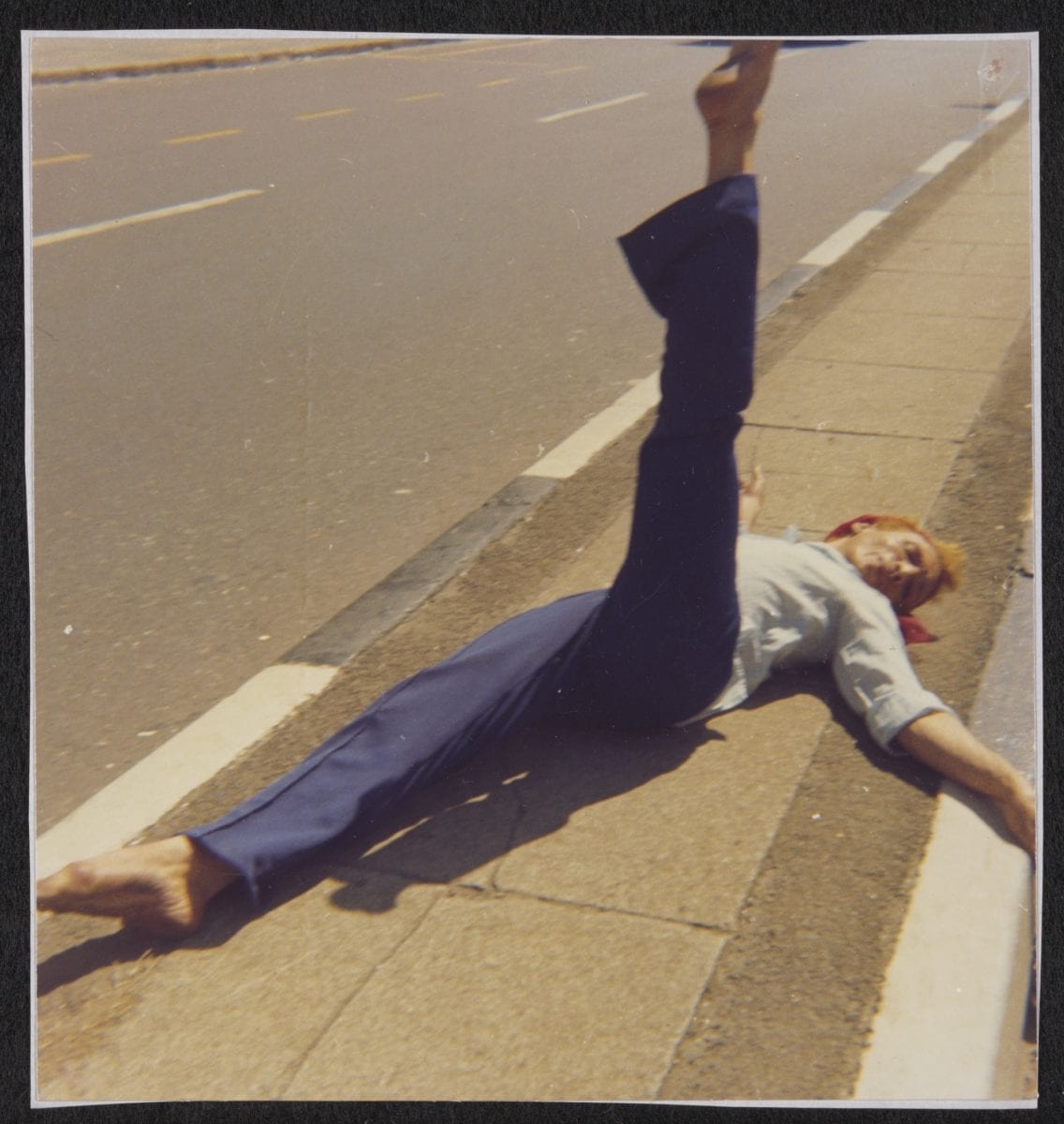

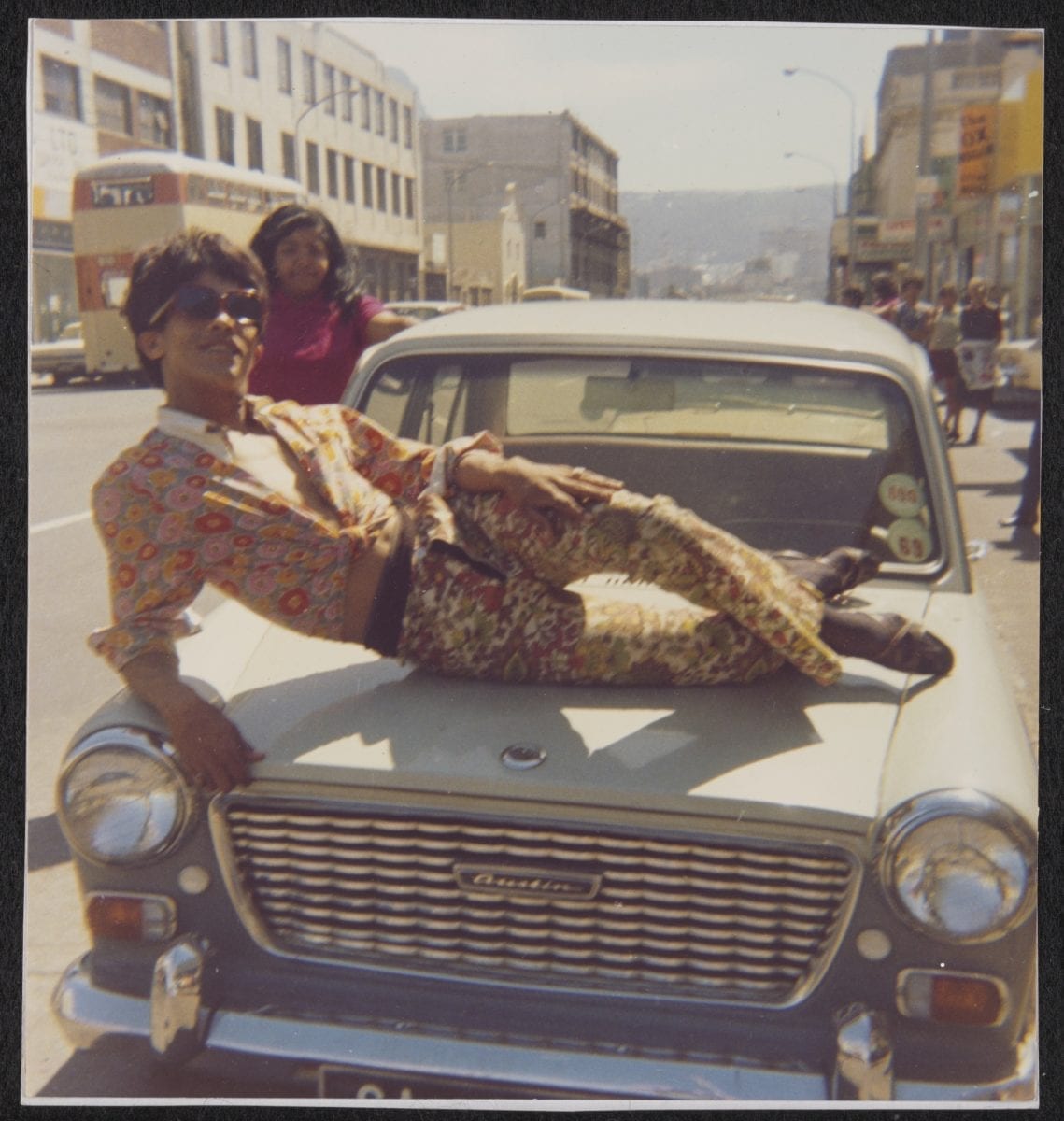

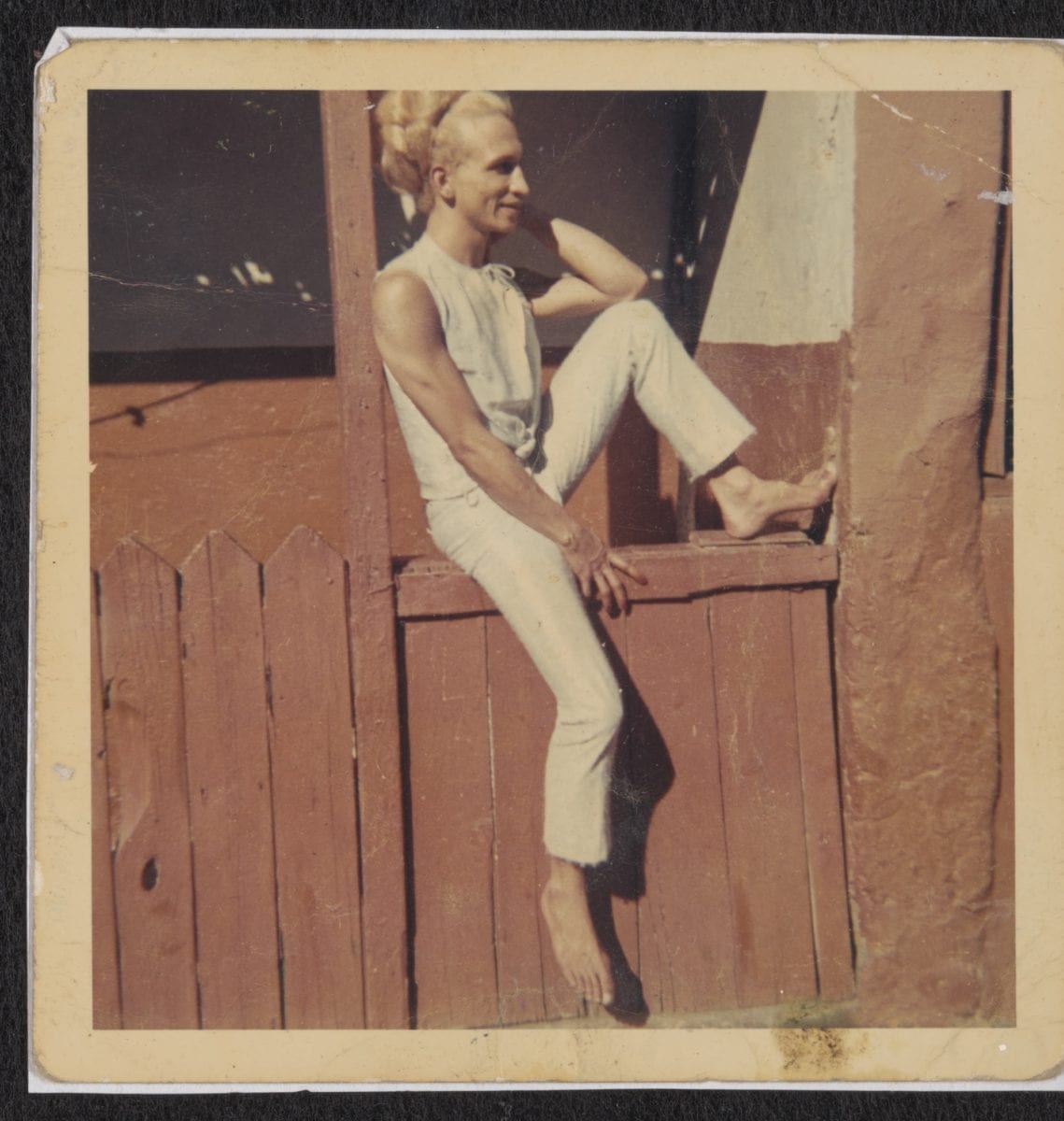

- Left: Kewpie Lies on the Ground on Sir Lowry Road, circa 1960 to 1985. Right: Olivia on a Car, circa 1960 to 1980

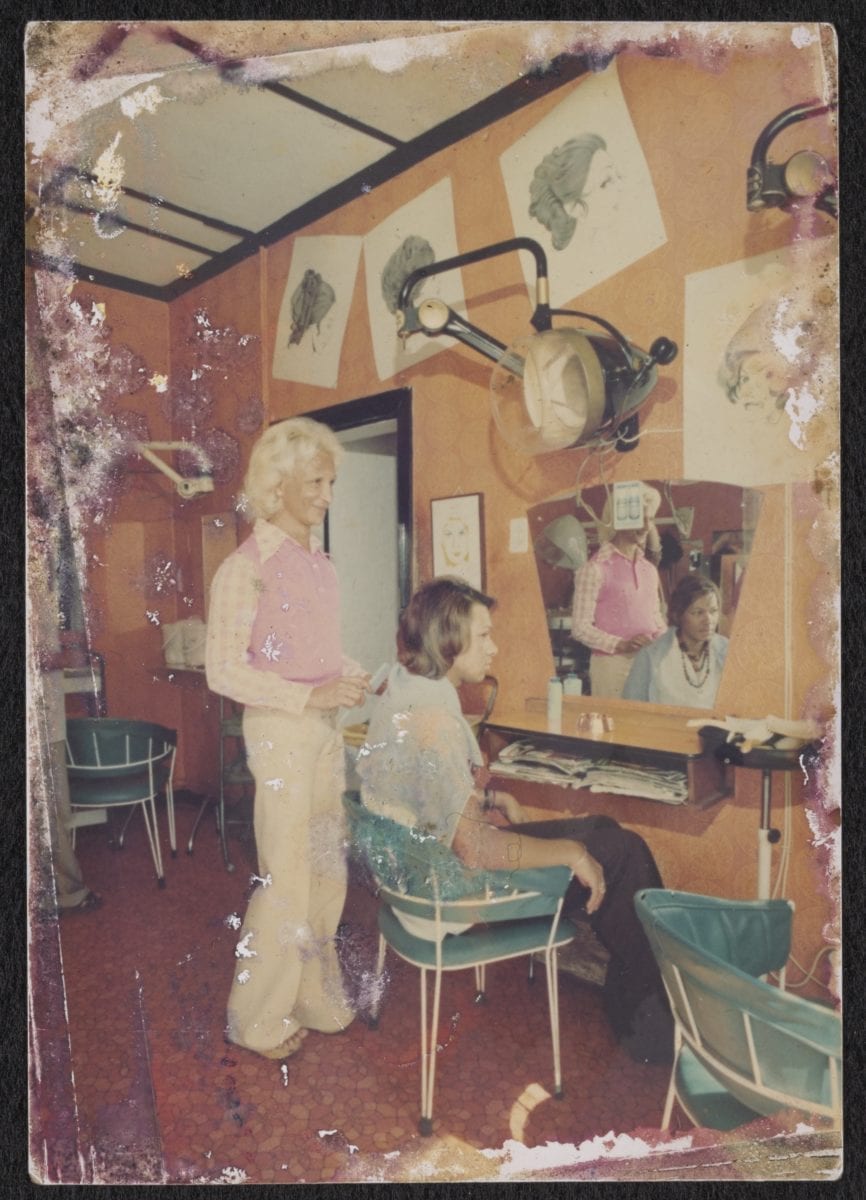

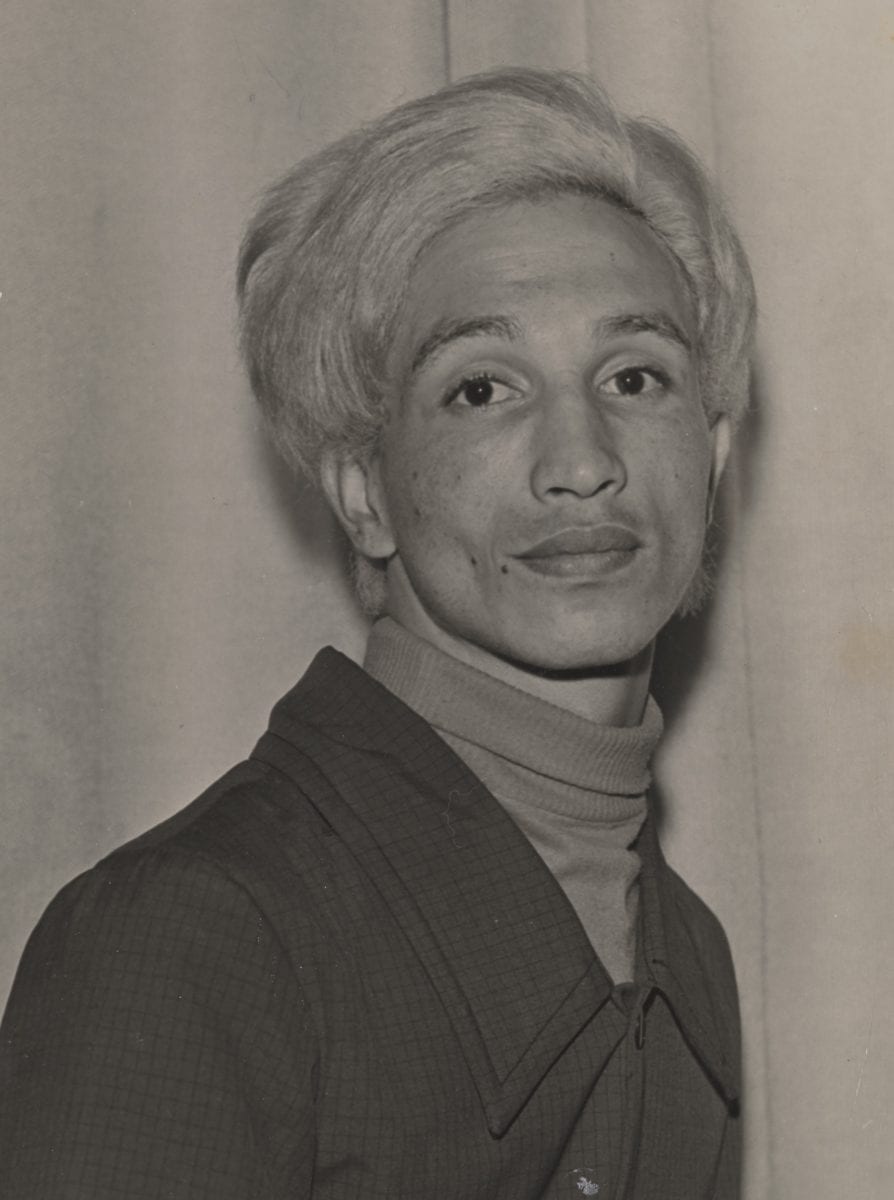

Kewpie (1941–2012), born Eugine Malcolm Fritz, was a hairdresser and celebrated queer icon who lived and worked in Cape Town’s District Six before the apartheid government forcibly removed residents to the Cape Flats. This was done through the Group Areas Act of 1950, which declared District Six a whites-only area.

Although Kewpie was born male, she traversed and blurred the lines between man and woman, complicating gender binaries, perhaps seeing heteronormativity and strict definitions of identity as a trap. She was often quoted as declaring, “I’m naturally just me, people can’t say I’m a man, they can’t say I’m a woman.”

The Kewpie Collection birthed a photographic exhibition—Kewpie: Daughter of District Six—initially staged at the District Six Homecoming Centre (Sep 2018 to Jan 2019) in Cape Town, with a second iteration at the Market Photo Workshop

in Johannesburg (May to July 2019), curated by Tina Smith, Jenny Marsden and Karin Tan.

“Although Kewpie was born male, she traversed and blurred the lines between man and woman, complicating gender binaries”

My interest in this personal collection of photographic images stems from my curiosity into narratives of mobility, and how womxn experience space and navigate through that space. I am interested in investigating various strategies of survival when one lives in a body that is politicized. As a young black womxn living in Johannesburg, a city with pervasive rape culture and one of the highest rates and worst cases of violence against women, children and queer bodies, this question of mobility—the ability to move freely and easily across the city—is constantly on my mind.

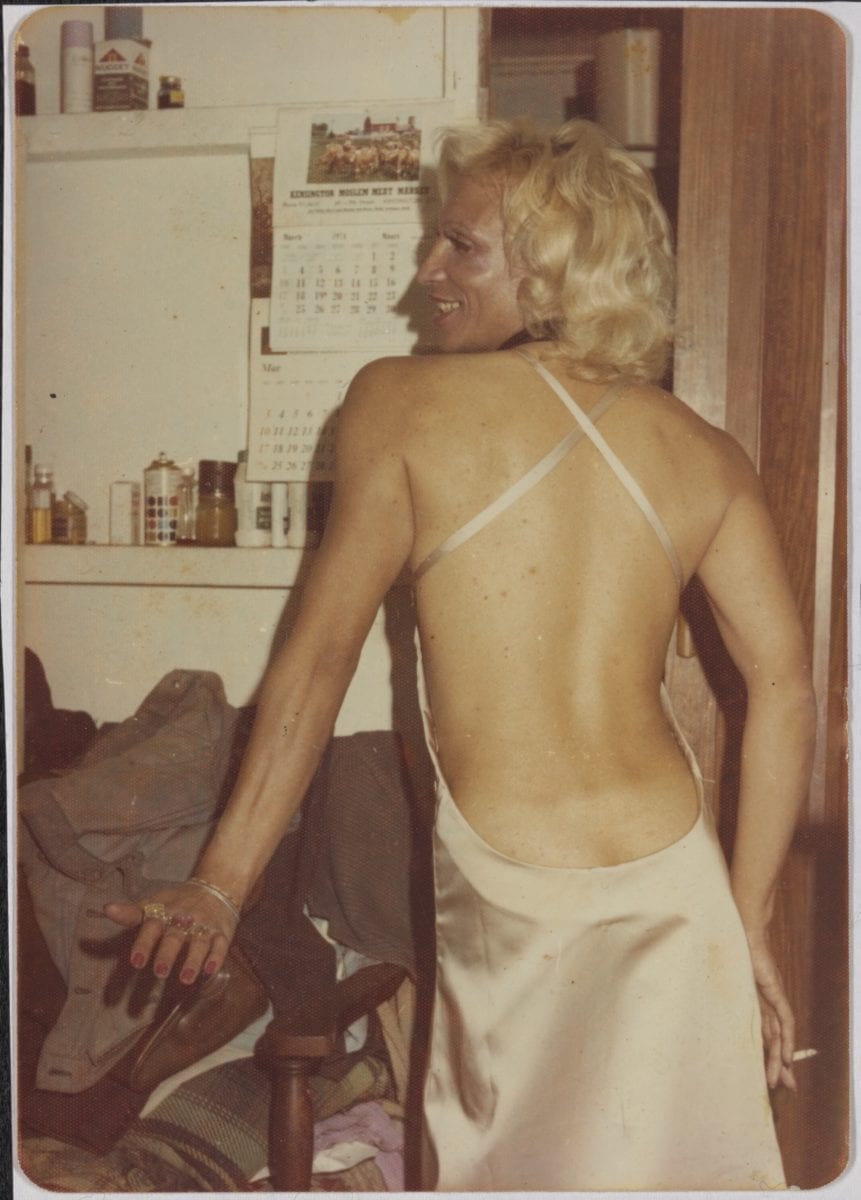

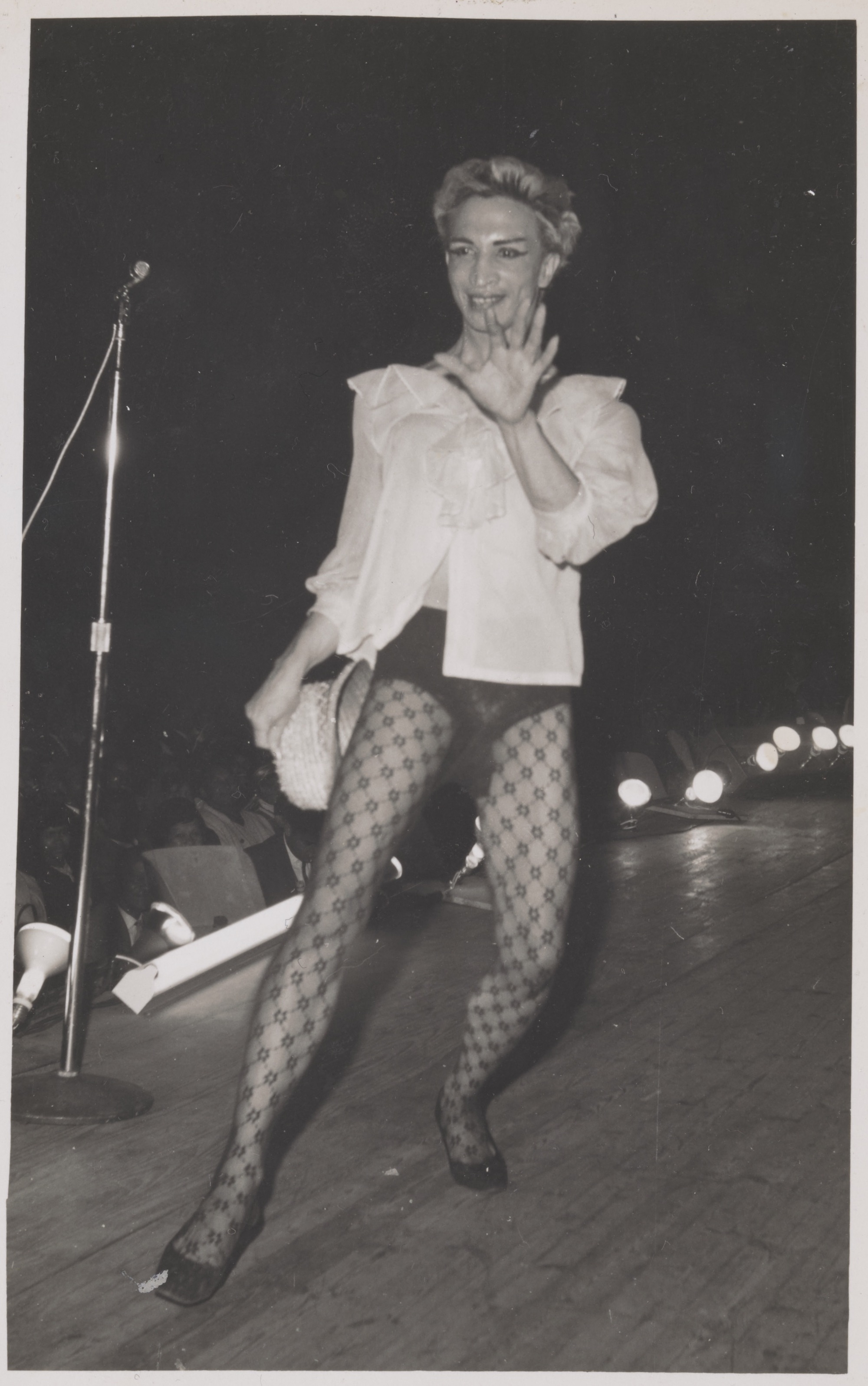

- Left: Kewpie Prepares to go to a Party, circa 1955 to 1985. Right: Kewpie Working in her Salon, circa 1978 to 1979

After encountering this archive, and reflecting on the nuanced moments of Kewpie’s life through these images, I began to observe Kewpie’s relationship with space. I thought of the ways in which we can begin to understand how various womxn have historically negotiated their ability to move in and around cities, helping us rethink our experiences of what we might call “spatial freedom”.

Here the term womxn (instead of woman) takes on a very specific meaning; referring to any individual who self-identifies as a woman, expanding the definition beyond binary biological categorizations of male and female, with an understanding that not all women are female and that the experiences of being a woman vary greatly. Womxn is a queering of how society reads bodies.

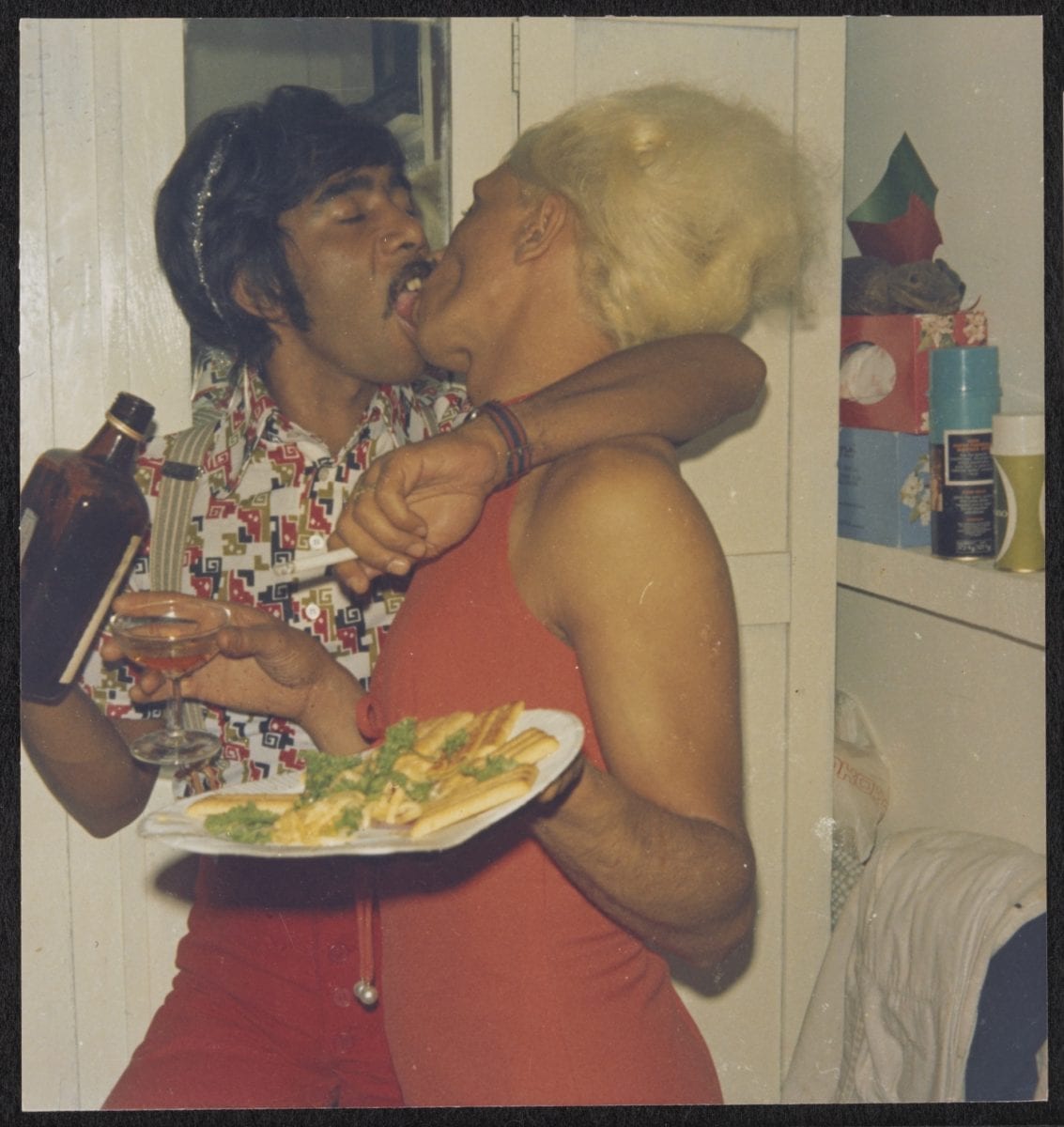

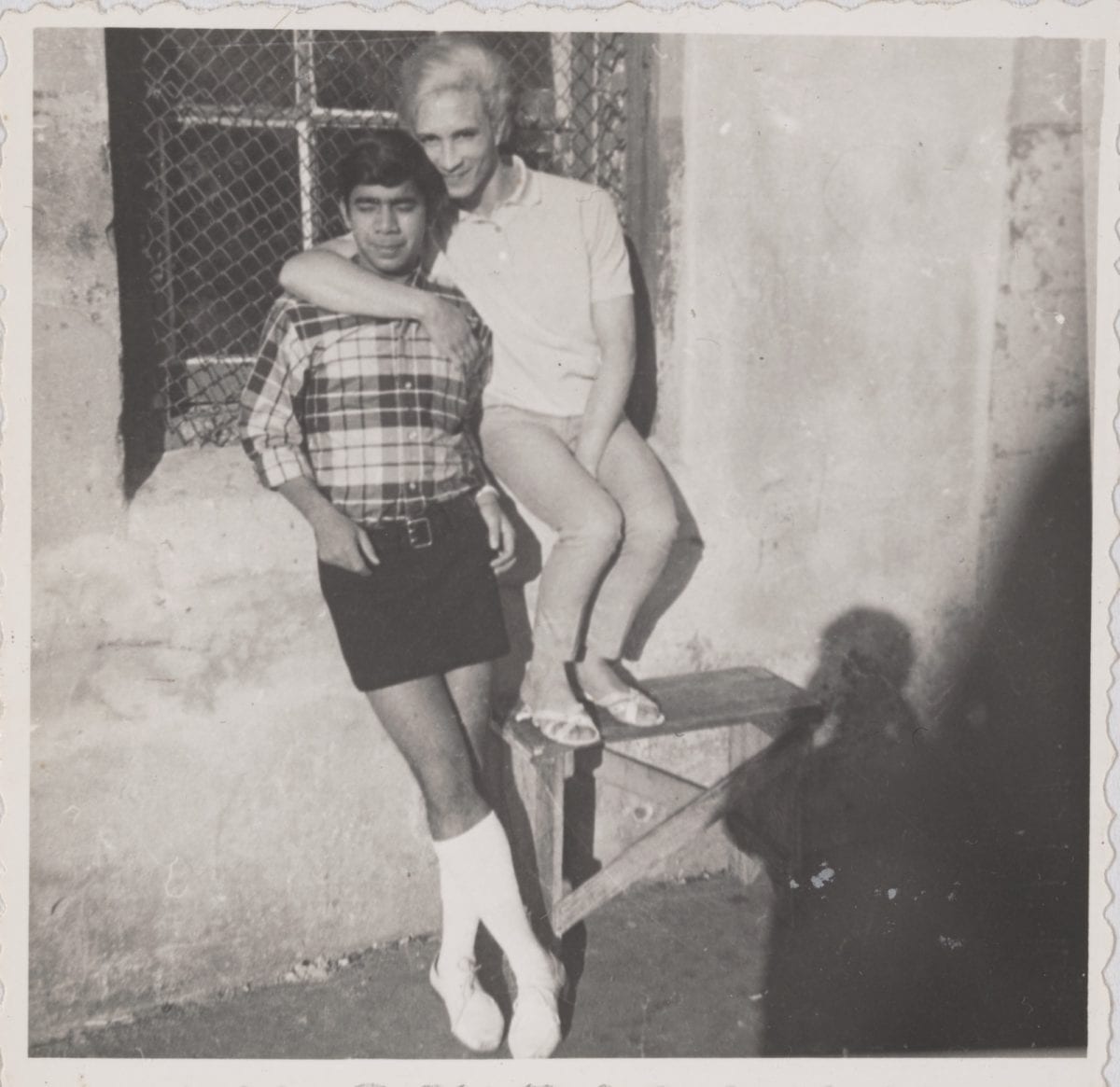

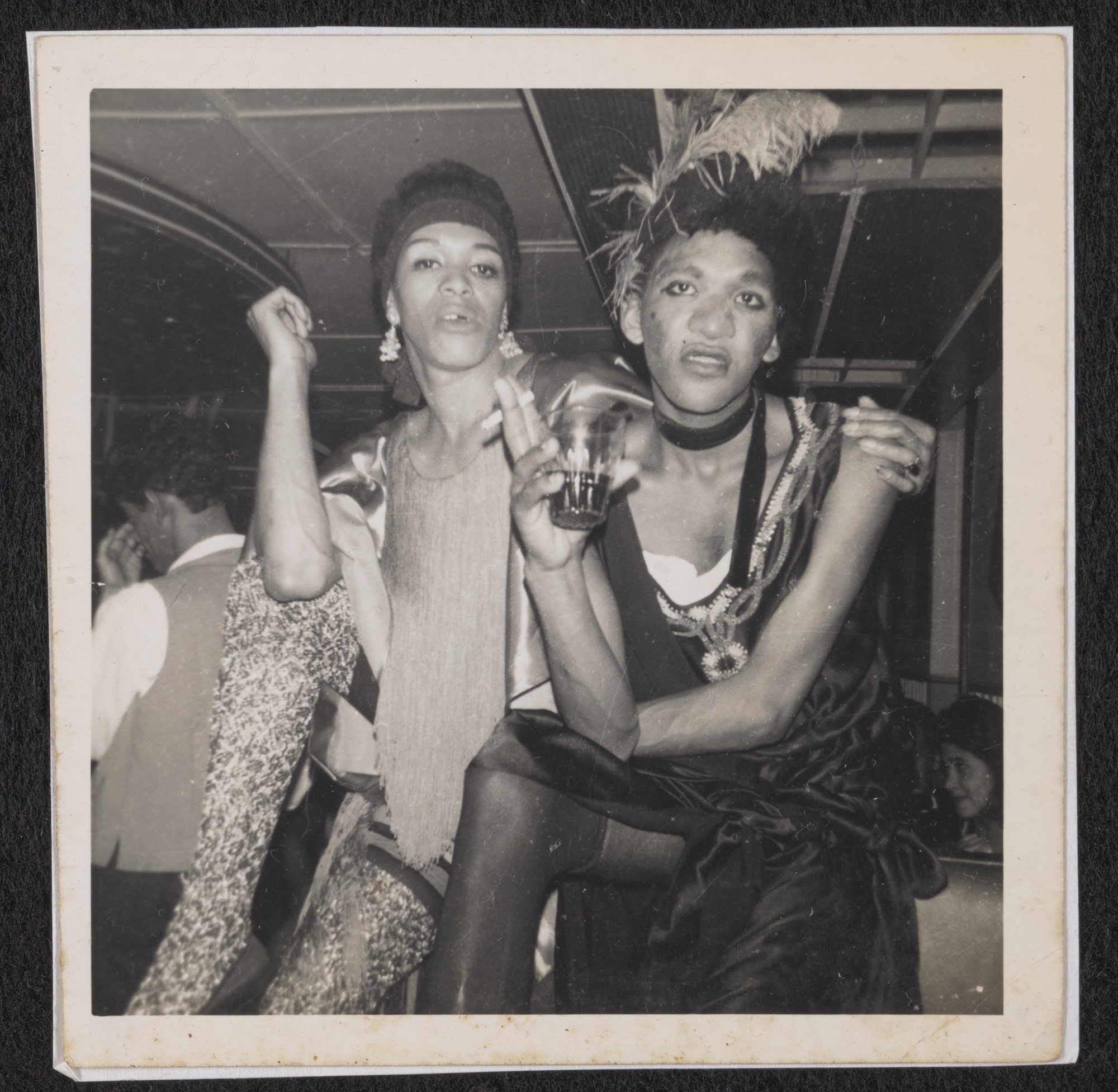

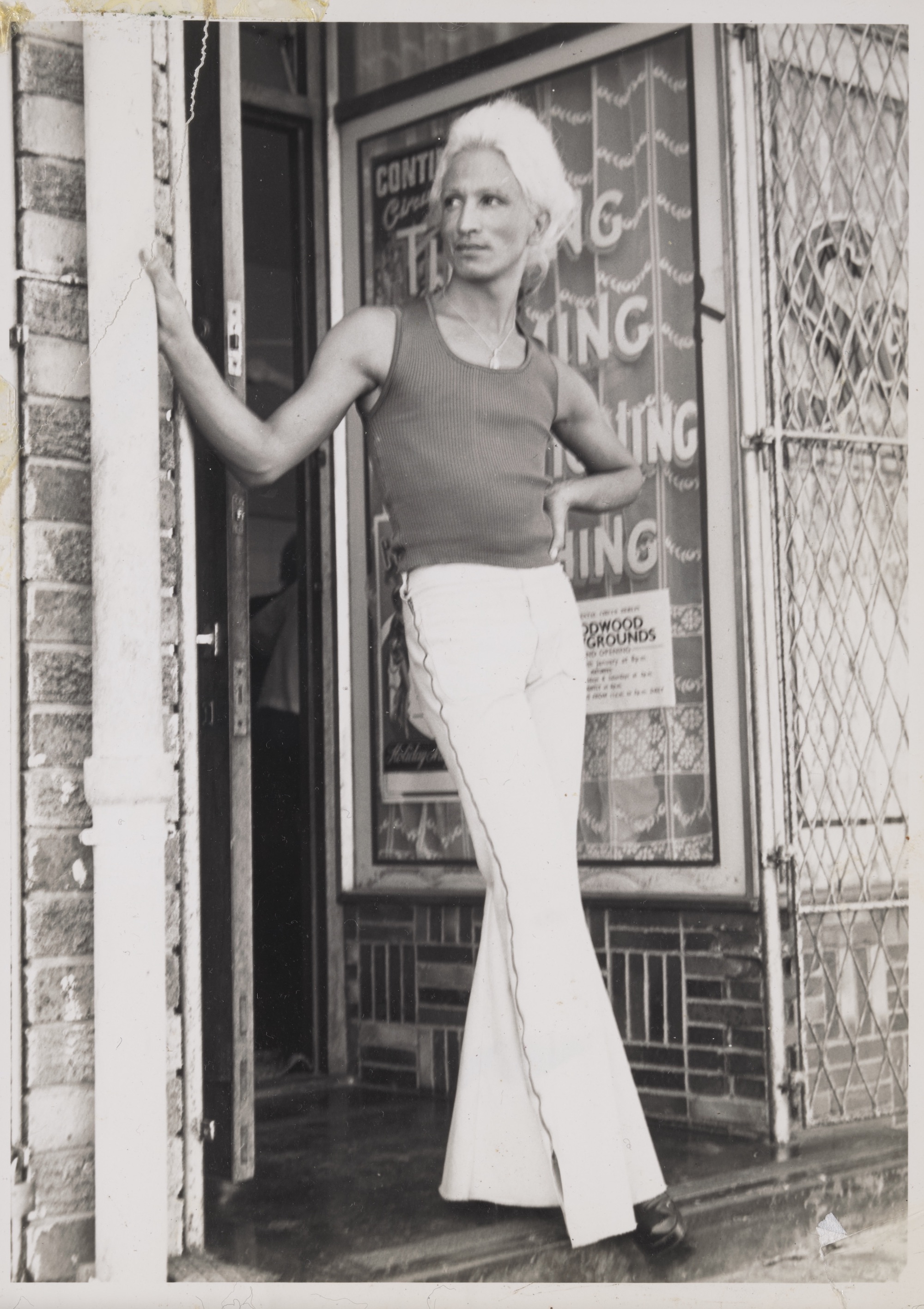

Throughout the Kewpie Collection, we see images that suggest playfulness and lightheartedness, constantly flirting with glamour, attractiveness and desirability. Photography can be seen as a deliberate tool used by Kewpie and her friends; choosing how they want to present themselves and choosing how they wish to be seen. They would often refer to themselves as sisters or girls, naming themselves after famous Hollywood actors and singers — Piper Laurie, Leslie Caron, Sue Thomspon, Julie Andrews or Doris Day.

Their pursuit of glamour might at first glance seem frivolous. However, when we begin to consider identity politics and the politics of looking, we are reminded of how power is tangled up with notions of beauty. Millions of people who do not conform to mainstream standards are sidelined and deemed unseeable, unsafe and unworthy.

Glamour and attractiveness can become acts of resistance, or at the very least a strategy to access the privileges reserved only for a few. This strategy is not without its own complexities, in that it might be read through the lens of the politics of respectability—whereby marginalized groups self-police their own behaviour and appearance, and compatibility with dominant values is encouraged and not questioned. We continue to grapple with these issues as a society; who should be seen and how should they be seen?

“Glamour and attractiveness can become acts of resistance, or at the very least a strategy to access the privileges reserved only for a few”

To echo South African visual artist and activist Zanele Muholi’s sentiments captured on a documentary series Art21 (Art in the Twenty-First Century), “There are a lot of beautiful humans out there who get to be on the cover of magazines, and they are loved dearly. Why are ordinary people only featured in any magazine when there is tragedy? Why are there no images of queer people, especially queer black people, and yet people are told that you have a right to be? I just wanted to produce images that spoke to me as a person…”

There is a risk that we may begin to overthink the Kewpie Archive, reading into the images what was never intended by its author. Kewpie died before the collection could be made public through an exhibition, which means she is not in fact able to respond to the ways in which the images (and to an extent her life) are read.

This point was aptly noted by one of the exhibition curators Karin Tan: “As GALA’s position of an archival entity, it is important that we don’t overstep our jurisdiction as an archive by overly theorising, constructing or interpreting Kewpie’s life, but rather presenting it to be read and interpreted.” In order to remain respectful and to avoid misinterpretation and mistranslation, it becomes critical to be clear about what we are reading into the images and the extent to which those readings reflect our own experiences.

I find it interesting how Kewpie chose to caption the images before handing them over to GALA. These gestures and their particularity, in terms of how she is consistent (and almost insistent) on names and locations where the images were taken, created a space for me to reflect more on this idea of spatial freedom.

“From the most intimate shots, taken in bedrooms and living rooms, to various streets, hotels and clubs, there was Kewpie, existing and being”

Moving freely around the city, as a queer body, between the 1950s and 1980s would not have been very easy. And yet Kewpie and her sisters seem to be challenging this. Through these handwritten captions, a mapping of sorts begins to emerge. From the most intimate shots, taken in bedrooms and living rooms, to various streets, hotels and clubs, there was Kewpie, existing and being.

“Kewpie In Her Bedroom, Preparing to Go to a Party”; “Mitzi, Kewpie and Brigitte in Invery Place”; “Kewpie in Rutger Street”; “At the Trafalgar Baths…”; “Samantha and Kewpie in the Biggs’ yard in Kensington”; “At the Queen’s Hotel. Kewpie and Olivia”; “Kewpie in Sir Lowry Road”; “Brian at Fourth Beach”; “Kewpie at the Spanish night at the Ambassador Club….”; “Kewpie at Kogel’s Bay”; “Kewpie at the ‘Bob Scene’ at the Kensington Inn”; “Kewpie on a Neighbour’s Step in Francis Street”…

Kewpie’s handwritten captions act as intentional and detailed records of space and location, creating overlapping and intermingled maps of memories lived through, songs sung, meals shared and stories told. These new maps tear through the old lines drawn by an oppressive government to separate people based on the colour of their skin. They tear through the invisible lines dictating where and when womxn’s bodies can be present. They tear through notions of safe and non-safe spaces that limit womxn’s ability to move freely. They create new maps of possibility, of mobility and of freedom.

All images courtesy Gay & Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA)