In a bright, airy studio in central London, curators Imani Robinson and Rabz Lansiquot are talking me through Dead Yard, an exhibition by artist R.I.P. Germain—their first as curatorial fellows at Cubitt gallery. Comprised of sculptures and a sound piece responding to the deaths of the artist’s family members, the show is inescapably commemorative, but it is also transitional: the bare white walls give the space a feeling of a heavenly waiting room—an opportunity to say goodbye, but also to reflect on the state of mourning itself. When rain seeps through the roof’s slanting windows, Robinson reaches down to wipe it away from the children’s books which form part of one installation. Dead Yard has a careful, precise harmony; Languid Hands are its creators and facilitators, but also its guardians.

The show explores Black mourning by using the deaths of R.I.P. Germain’s close relatives: Lloyd, his grandfather; Imarl, an infant cousin who passed away at only a few months old; and Sonny, an uncle (among others), as part-stimuli, part-opportunity for embodied remembrance. Death-as-event is acknowledged by the exhibition’s very existence. R.I.P. Germain’s intention is to go further, to address death as a perpetual state of being: underexplored, ineffable, and, for Black people, highly specialised within the contexts of white supremacy and racial injustice.

“There’s a lot of detail in this show, but R.I.P. Germain didn’t have to explain the nuances of that detail, because we can understand them”

For Languid Hands, it was a natural pairing. Their practice is focused on creating inclusive, collaborative spaces for Black artists to present their work: “it’s a lot about being a hype man,” Robinson says, paraphrasing their partner. “Creating opportunities for people, allowing people to have a space that they need and that they aren’t necessarily given elsewhere.” With a project as personal as Dead Yard, the process of curation is predominantly spatial, Robinson explains. An artist may have an idea about what they want to include in a show, but the curator’s role is to arrange objects so that meaning can be communicated in a balanced, accumulative way. For Languid Hands, trust and authenticity are perhaps the most important ingredients. Their origins are the shared elements of Black experience.

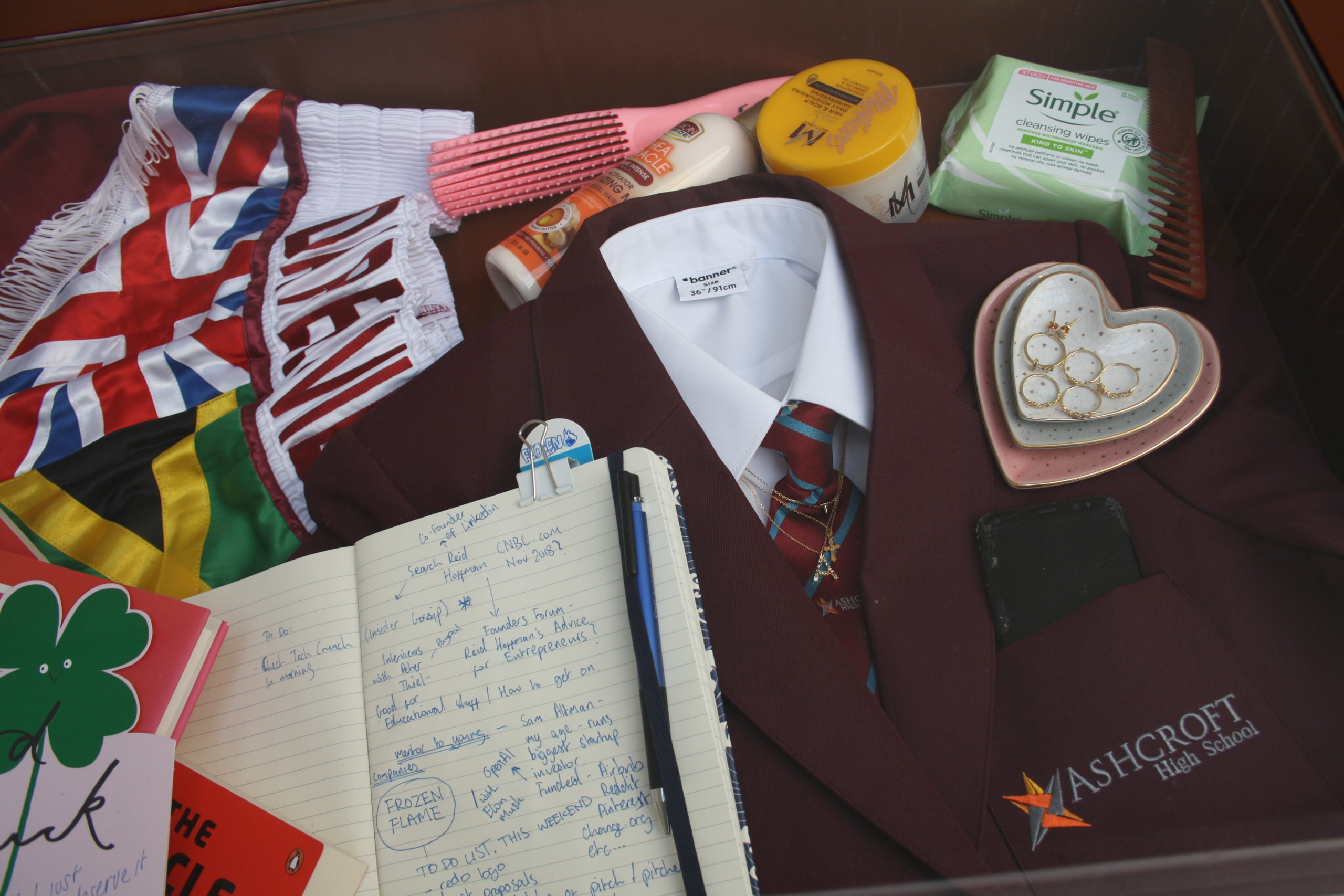

“There’s a lot of detail in this show, but R.I.P. Germain didn’t have to explain the nuances of that detail, because we can understand them,” says Lansiquot. Dead Yard’s centrepiece is a recreation of a moment at Sonny’s funeral, which the artist was unable to attend. Family members sat around a table playing dominoes and partaking in other Caribbean mourning rituals, with a portrait of Sonny resting on a vacant chair. Reimagined at the far end of the gallery, the empty chairs have various objects laid upon them which speak to the complexity of Black death: on one, a framed bloodied shirt. On another, an octopus toy (a metaphor for grief). The table itself houses objects from Union Jack boxing shorts to DVDs.

The realities of Black existence—in both life and death—are here a binding creative force. This affinity transcends the typical artist-curator relationship; the result is that Languid Hands only collaborate with artists with whom they have an intimate friendship. Without this bond, work simply cannot cohere in the same way. “We became curators because we were Black artists interested in working with Black artists,” says Robinson. “And we don’t need a middle man or anybody else to be able to do that.” Community is an expected and natural product of these exchanges. Their Cubitt fellowship, entitled No Real Closure, features Black British artists of Caribbean descent—redressing underrepresentation within Black British commissioning as a whole. “We’re trying to reclaim a radical Caribbean lineage,” says Robinson.

“We became curators because we were Black artists interested in working with Black artists. We don’t need a middle man to be able to do that”

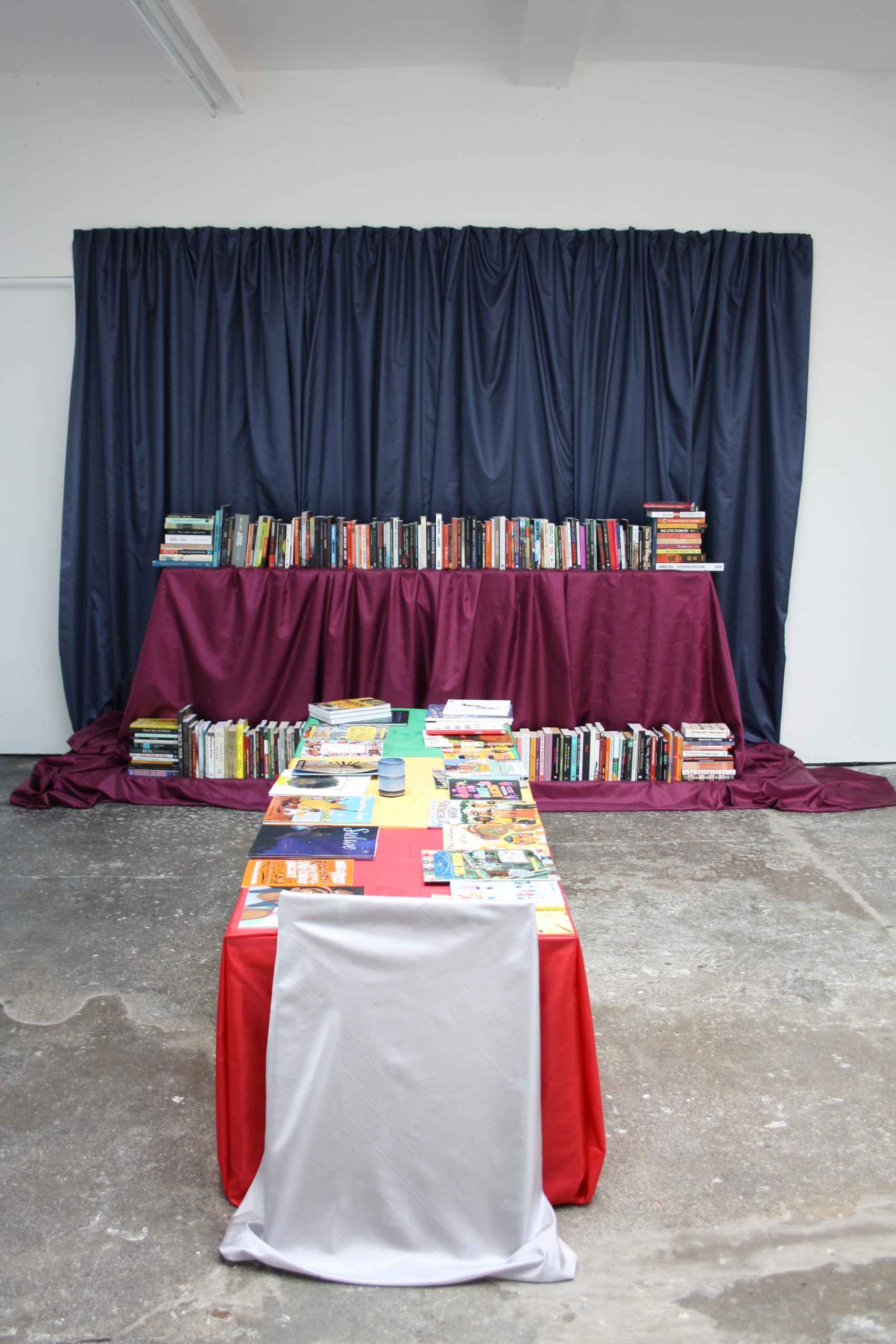

The understanding Languid Hands look to generate with artists is as much theoretical as experiential. At the opposite end of Dead Yard is a library installation of over 300 books, most of them on Black and queer politics. Frantz Fanon, Toni Morrison and Octavia E. Butler sit alongside more recent academic contributions on BAME mental health and accountability within community organising. The library is a reminder of those who have gone before—and the length and unevenness of the road ahead. “We’re under no kind of illusion that we’ll be making work in our lifetime that is not within the contexts of anti-Blackness and white supremacy,” says Robinson. “That is not within the contexts of environmental destruction; state violence; a kind of all-encompassing carcerality based in coercion and punishment. And it’s our responsibility to respond to that.”

Robinson and Lansiquot both grew up in London, in Notting Hill and Brixton respectively. They first came to public prominence as leading members of sorryyoufeeluncomfortable (SYFU), a London-based creative collective with origins in the Baldwin’s Nigger Reloaded

project. Ever since 2014, when two artists (one of whom was Barby Asante, Lansiquot’s mother) sent a callout for young creatives to respond to Horace Ové’s 1968 film, Baldwin’s Nigger, SYFU has been using the documentary—and Black radical thought more generally—to inspire events and workshops, including at London’s Somerset House Studios and Institute of Contemporary Arts.

“The difficulty with a predominantly white art world is that eventually, projects like SYFU are viewed as an educational resource to be tapped by white audiences”

After working on (BUT) WHAT ARE YOU DOING ABOUT WHITE SUPREMACY?, a SYFU exhibition at Glasgow International 2018, Robinson and Lansiquot explained the group’s ethos in an interview. Members of the majority non-white, non-heterosexual group “were often made to feel unwelcome in art spaces, with both our politics and our being-in-the-space always seeming to make other people flinch,” the pair said. “The name, SYFU, operates with multiplicity, it’s shady and sarcastic and on-the-nose and also an act of care and recognition for each other.” But looking back, says Lansiquot, the group was asked to perform a lot of institutional critique as name recognition grew. The difficulty with a predominantly white art world is that eventually, projects like SYFU are viewed as a kind of educational resource to be continually tapped by white audiences only just waking up to the social, economic and political realities of Black life. Artists’ work can become obscured in the process.

“With Languid Hands, we have to try and create an identity for ourselves that’s not just ‘those Black people’ or ‘those Black people who are doing that Black thing,’” Lansiquot continues. “And that’s a challenge, because once you utilise those terms or you’re explicit in your politics, it’s very easy for that to be co-opted into that representational sphere.” Thus far, Languid Hands has allowed the pair to be more nimble and attentive to emerging Black artists, partly because of the financial security offered by fellowships like Cubitt’s. The pandemic meant that new commissions due to be shown in April were postponed; in their place, Languid Hands are creating a publication of essays and commissions responding to their 2019 film Towards a Black Testimony. The next show in No Real Closure, scheduled for February 2021, will feature photographer Ajamu X, whose portraits depict young Black queer people.

To a first-time viewer, there is a tension which runs through all of Languid Hands’ work: on the one hand, their practice explores Black life with a near-nihilist sensibility—heavily influenced by

Afropessimism, and, like Dead Yard, a thematic concern with Black death, mourning and extinction. On the other, their work is tied to a powerful strain of forward-thinking activism: aspirational, insistent and drawing on ideas like prison abolition and Afrofuturism. Can optimism and pessimism be reconciled?

Towards a Black Testimony epitomises the balance that Languid Hands find between the two. The 40-minute film draws on archival protest and festival footage, with Robinson’s narration overlaid the often joyous imagery. The project explores the impossibility of Black confession and declaration—particularly how the denial of testimony amounts to a destruction of Black subjectivity in both social and legal contexts. Drawing on Afropessimist ideas around the legacy of perpetual non-existence from the transatlantic slave crossing, the film also prefigures debates surrounding protest strategies and incarceration which have come into sharp focus this summer. “If I die in police custody, burn buildings down. No building is worth more than my life,” the narrator says at one point.

- Towards a Black Testimony (stills), 2019. Courtesy Languid Hands

“The film explores the construction of Black people as not human” says Lansiquot: “But it doesn’t necessarily think of that as just a negative thing. It creates space for the possibilities if we think beyond the human. And building from that as opposed to trying to claim humanity and inclusion into systems and ideas that don’t work for us.” A recognition of systemic inequality here leads to pragmatic, experimental survival: optimism borne out of pessimism.

“We’re under no kind of illusion that we’ll be making work in our lifetime that is not within the contexts of anti-Blackness and white supremacy”

Robinson agrees that a simple binary is unhelpful for understanding Black creative practice: “I am able to be optimistic because I understand what pessimism has to give us,” they say. “Because I understand the painful and ongoing realities of anti-Black violence. I can sit with those things and be present to them—that makes the joy and the futurism possible.”

In Away, Completely: Denigrate, a Languid Hands-curated group exhibition earlier this year, artists responded to the etymology of the word denigrate. Its origin, “to blacken, completely” or “to make black”, reveals “the anti-Blackness that is inherent in the English language,” say the pair. Again, recognising how anti-Blackness is re-inscribed in every facet of life offers clarity; the artists can then respond in the knowledge that they’re working within a shared, substantiated ideological framework—a space consciously created to support them that few other curators can provide. Dead Yard’s success is testament to this ethos.

Languid Hands’ practice is ultimately holistic: a curatorial project which aims to widen, not narrow the radical possibilities for Black inclusion, from abolitionist politics to community-fostering. “We learnt from our elders that attentiveness to Black arts and Black politics wanes,” Lansiquot says. “Support ebbs and flows. But our commitment to Black liberation and liberatory practice within the arts doesn’t. Because anti-Blackness doesn’t ebb and flow. It is always there. And we know that it’s not going away in our lifetimes.”