The exhibition is the first ever investigation in a museum into the practices of one hundred women artists, either born in the US or in Latin America, but with a shared heritage, working during a turbulent political period dominated by the Cold War and repression. During those years, FARC had formed in Colombia, the beginning of ongoing violence that would take the lives of more than 220,000, in Chile, Allende committed suicide and Pinochet took control of the country, and Mexico was locked in a bloody internal conflict, with student and guerrilla groups fighting against the US-backed government.

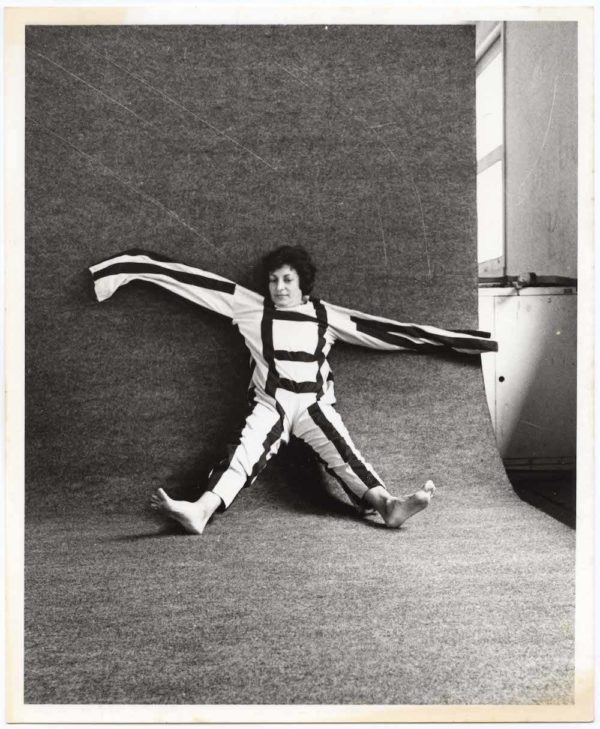

As the curators note, there has been a gaping hole in art history and in the public consciousness around these women, the work they did in their contexts and their wider influence, including in the mediums of video and photography (which dominate the exhibition), but also the way they contributed more widely to the ideas and impulses of contemporary art movements.

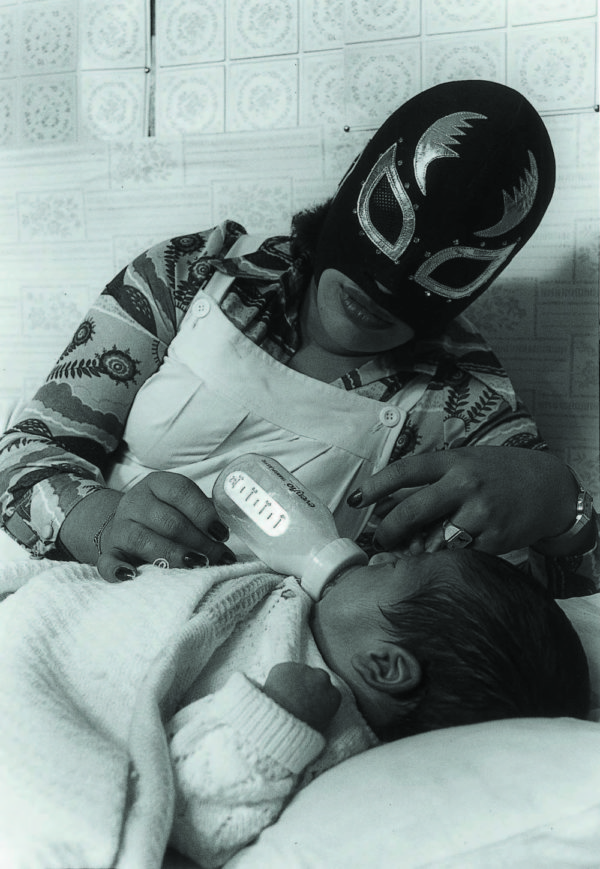

Among the artists yet to be properly canonised are Lourdes Grobet, the Mexican photographer, now seventy seven. Growing up, Grobet watched the Lucha Libre on TV, but not being allowed to attend fights, she picked up a camera as a way of getting close to the luchadores, and has continued to document Mexican wrestling for twenty-five years. Like Grobet, Pananaman photographer Sandra Eleta (who shot portraits along the country’s Caribbean coastline in the 70s and 80s and founded the Portobelo Group, opening up her home to local artists to show their work) provides an important independent social and cultural document that has been largely ignored.

Another almost-lost artist brought back to life by this exhibition is Brazilian artist Letícia Parente who died in 1991. Radical in both form and content, her experimental video work includes a silent film she made in 1975, Trademark, in which she sewed the word “Brasil” into the sole of her own foot, in black thread. In another film, she lies face down on an ironing board while the clothes she wears are ironed by a maid. In addressing Brazil’s military regime of her time, Parente’s work has almost been obliterated by political oppression. Her later work began to touch on themes that extend outwards, such as the imposition of behavioural ideals on women.

“What this exhibition does reflect by its breadth is how interconnected the struggles of women are, in the art world, in history and in the present.”

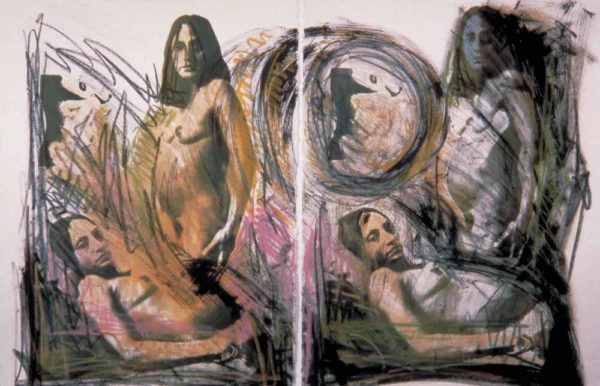

The narrative of women’s art being ostracised and sidelined is, sadly, hardly new or surprising. Although perhaps overly extensive, given that it includes more than two hundred works coming from fifteen different countries simultaneously, what this exhibition does reflect by its breadth is how interconnected the struggles of women are, in the art world, in history and in the present. This is not an exhibition that speaks only about place, gender and history, but about people. In the words of the late Ana Mendieta—whose death in 1985, having fallen thirty-three stories from an apartment window, remains controversial—”My art is grounded in the belief of one universal energy which runs through everything: from insect to man, from man to spectre, from spectre to plant from plant to galaxy. My works are the irrigation veins of this universal fluid. Through them ascend the ancestral sap, the original beliefs, the primordial accumulations, the unconscious thoughts that animate the world.”

Sonia Gutiérrez, (Colombian, b. 1947), Y con unos lazos me izaron (And they lifted me up with rope), 1977. Acrylic on canvas. 59 1/16 × 47 1/4 in. (150 × 120 cm). Museo de Arte Moderno La Tertulia, Cali, Colombia. Courtesy of the artist. Artwork © the artist.