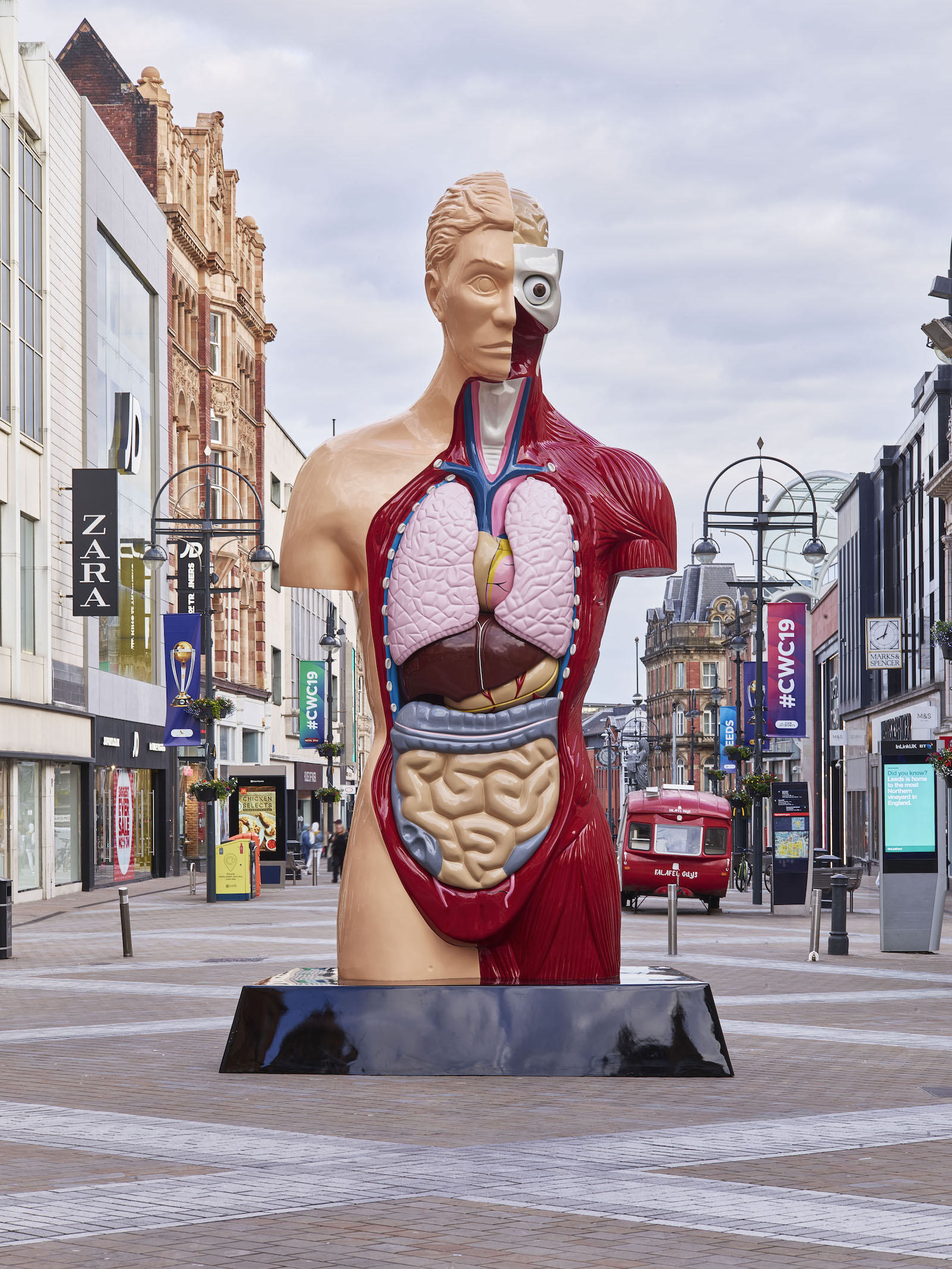

There were many things I expected to see at the first edition of the Yorkshire Sculpture International; a woman urinating, a dissected pregnant woman and a prehistoric cyborg weren’t among them.

I did expect something different: the festival has been quiet about it, but the majority of the selected artists are women (twelve out of eighteen). Considering the fact that the most monumental sculptures (in both stature and fame) to date are by men, this is a pretty rousing clarion call in response to the usual place and purpose of sculpture in public spaces (as a huge creative phallus).

“The impulse to make things with our bare hands is very human”

The premise for this one-hundred-day event comes from a “provocation”—is there anything more artspeak—from Phyllida Barlow, who is otherwise absent from the event, save for a quote printed on a red tote bag. Barlow had come up with more than sixty statements last year for the festival organizers—and they decided that “Sculpture is the most anthropological of the art forms” was the most compelling. It feels cerebral enough for curators to get their heads around, but perhaps too opaque a statement for getting people who aren’t interested in sculpture, or even art, to engage with it. I didn’t find any answers to Barlow’s enquiry in Yorkshire, but I did learn some things about sculpture that surprised me.

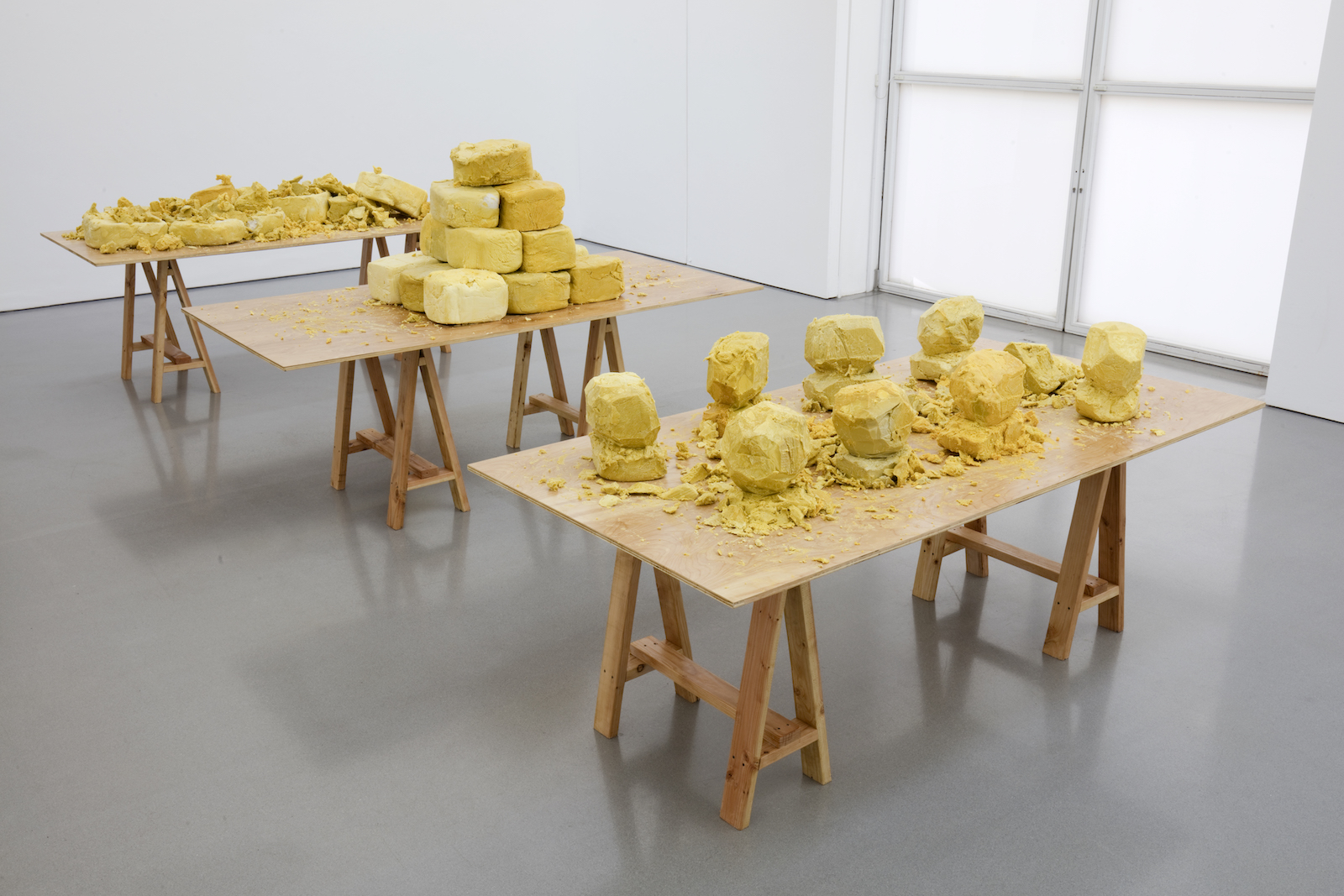

The impulse to make things with our bare hands is very human. I was reminded of this by Rashid Johnson, whose new work Shea Butter Three Ways, presents the rare opportunity to touch the art at the Henry Moore Institute. Three tables are laden with lumps of the ochre-coloured substance, the first two assembled by Johnson to recall the imposing busts of Western antiquity and the high-minded Minimalist art movement—both touchstones in Johnson’s work, hinting at power and knowledge. The third table is presented ‘raw’, with piles of shea butter for the audience to play with. It is all beautifully brought together by the history and associations of the butter itself, erotic and exotic in its connotations, imported from Africa and used to beautify in the West, to heal and smooth. I found myself diving in with both hands, squelching and squishing with gusto. No shapes came to mind but it felt good—you don’t have to get all the nuances of the work to understand something much more basic about art and why people do it. The smell and feel of the shea butter—a product layered with racial, social and political meanings—stayed with me long after we left the gallery.

“The most prominent message at the Hepworth is how sculpture can be used to ‘subvert a sense of superiority’”

Tau Lewis

At the Hepworth Wakefield—one of the four institutes, alongside the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds Art Gallery and Yorkshire Sculpture Park, which are taking part—the lesson is that sculpture can emerge out of anything: a chunk of tree gifted to the artist Jimmie Durham by a collector is fashioned into form, poised seemlessly next to the Hepworth; in the next gallery, Wolfgang Laib was still laying out his palm-sized piles of rice when I visited—filling the room again with an overwhelming aroma. Also exhibited are new works by Tau Lewis, a very young and very bright artist who is inspired by the sea as both a setting and a metaphor—a place of hope and rebirth for black stories and mythologies. “Myth-making is important in filling spaces of erasure,” Lewis says, pointed out that storytelling is equally as important as theory when so much has been lost. Her role is to imagine: sewing and stitching by hand she has created a series of characters out of clothing and fabrics. “My mandate is to repurpose and recycle”, she explained.

Sculpture, unlike any other medium, has the possibility of getting in our way. Nairy Baghramian moves the viewer in all sorts of unusual ways through a series of precisely placed structures. The works themselves question positions and balance, but the way they are arranged questions the architecture of the museum, and how it makes us look. One physical relationship informs others—Baghramian provokes us to think about the way we move and interact. The most prominent message at the Hepworth is how sculpture can be used to “subvert a sense of superiority”—as Andrew Bonacina put it.

Over at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, where even a full macho combination of Damien Hirst and David Smith cannot dominate the spectacular landscapes (though they seem to try) there is also an exhibition of five women artists working in Yorkshire. One of them is Rosanne Robertson, who also presents sculptures and a video at the Hepworth—including her surprisingly pretty video, Pissing, of the artist urinated perched on a mountain crevice.

Hepworth’s sensual figures were a huge influence on Robertson, who grew up in Sunderland. “I always thought of her figures as genderless,” says the artist, who now lives in Hebdon Bridge. Her works explore water and stone, making a connection between fluidity and barriers, nature and queer bodies. She staged these interventions literally when making a new series of sculptures, by carving them back and forth the moors, between her home and studio—gruelling, especially in winter. She hopes to reveal the “unifying experience between the water in our bodies and the water in the ocean, and to link that fluidity to queerness”. Throughout history, she explains, queerness has been represented as something that is against nature, but forging this connection to water she breaks the barrier between her own body and nature and reinstates her identity. “Nature is ever-changing and we’re all part of it—I’m not saying that only a queer person has access to that, it’s in all of us.”

“You don’t have to get all the nuances of the work to understand something much more basic about art and why people do it”

A big initiative of the Yorkshire Sculpture International has been to reintroduce sculpture into art schools. Perhaps the most important lesson of all is the suggestion that sculpture can take many forms—and it doesn’t need to take time, or cost money. Nobuko Tsuchiya constructed her work ad-hoc, using the gallery as a studio; it feels spontaneous, light and desultory at the same time. Joanna Piotrowska and Rachel Harrison, hung next to each other, present versions of rough assembly and temporary structures as a kind of beauty, through photographs and three-dimensions. They’re works that insist on transience—not something you usually learn from a sculpture.

Many of the works on show in Yorkshire are transient too—Huma Bhabha’s celestial blue figure, alien and ancient-looking at the same time, faces an imperious statue of Queen Victoria, in the centre of Wakefield. It’s Victoria who will remain, come September, when the festival is over. “That’s REALLY weird!” exclaimed a group of teenagers passing by. Provocative or pretty, what the YSI’s first year proves is that sculpture here, rich in the past, still has a lot to teach us in the present and the future.