In the works of Rayyane Tabet, what is visible has an unseen tail of secret history and resonance. Entering his first London show at Parasol unit, the viewer is presented with two wooden oars suspended by ropes in the gallery’s high-ceilinged space. Impaling the air, they appear both brutal and still, worn and clean, but also somehow pathetic. They are from the boat his father rented when he attempted to escape the tail end of the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) with his family.

“The city centre became a building site that was only open on Sundays”

“We found the boat twenty-five years later while casually dining on the shore,” the artist tells me. “My parents were having an argument about whether it was the same one, and we actually stopped eating to go looking for its owner. An hour later we found his son, and he remembered us all. ‘You’re the crazy family who tried to row to Cyprus.’” Tabet acquired it and, along with The Sea Hates a Coward (2015), made another work called Cyprus for which the 850kg boat and its 60kg anchor are suspended from the gallery rafters, as immobile as it was on the waves when his father attempted to move it. “My dad is short and stocky and has never worked out a day in his life,” says Tabet. “The fact he attempted that journey is crazy.”

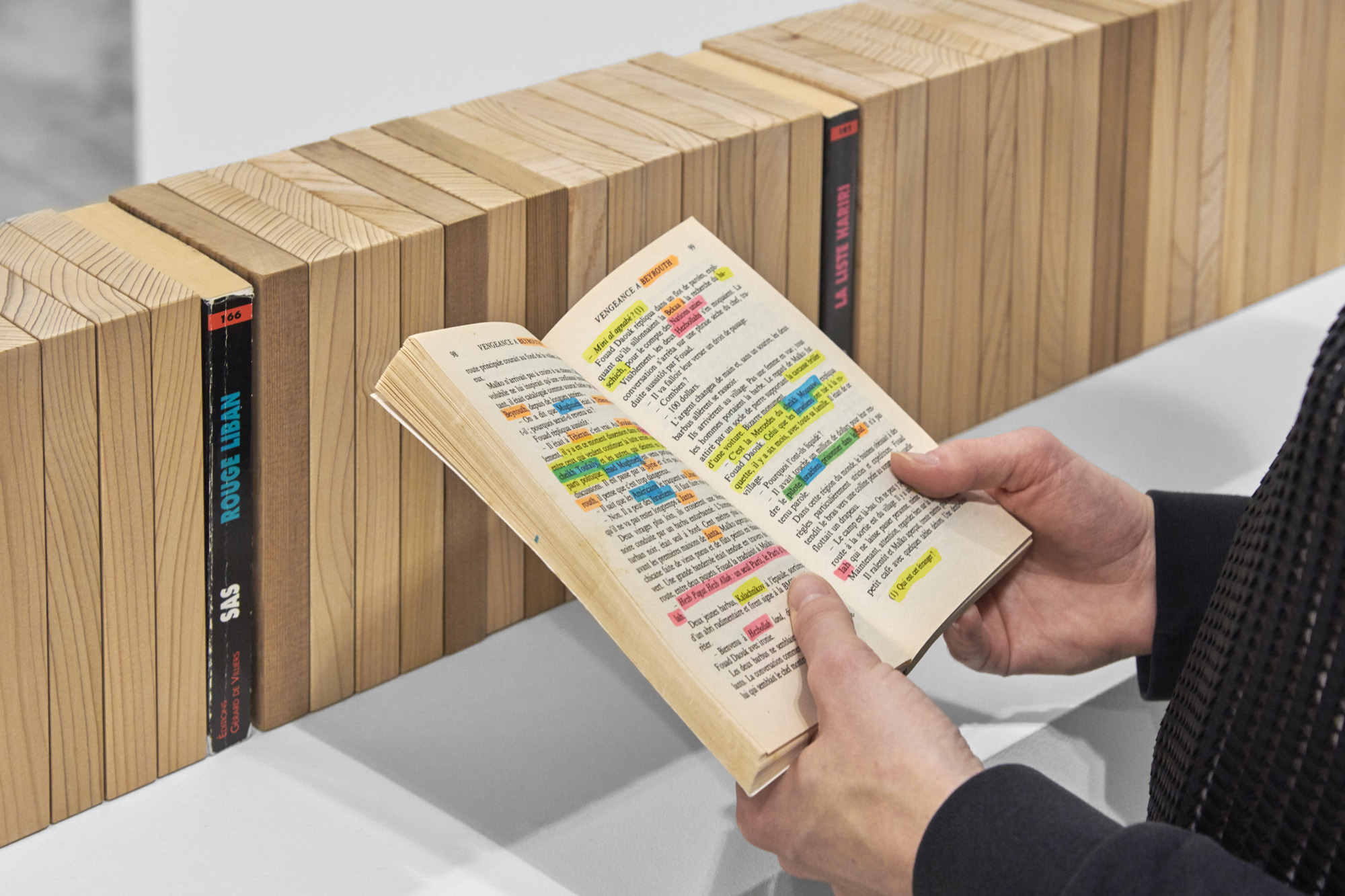

For over a decade Tabet has been creating works with an immediate physical presence to match their detailed intentions. Sometimes made from found objects, his sculptures and installations stand for incredibly rich and complete narratives with personal strands parallel to those of global politics. They might tell the story of Jørn Utzon, the architect who had a rocky time designing the Sydney Opera House and—the artist discovered—once worked on an unrealized Lebanese project. Or of the German diplomat and amateur archaeologist Max von Oppenheim’s discovery of Bronze Age reliefs in Syria, while working with the artist’s own great-grandfather. Or of the writer of French pulp spy novels Gérard de Villiers, who set six of his 200 books in Lebanon. The results are multidisciplinary. As well as being trained as an architect then a sculptor, Tabet also writes texts, binds books and brings performers into his installations.

The eight works in Encounters could be considered a sort of survey, and could be said to address how Lebanon is perceived by outsiders and even by the Lebanese, who, Tabet tells me, have no common history textbook. “Children in different communities are taught different versions of their history, and in all the versions each political party has won the war. There was no official loser, so no one gets to write that history.” I ask him about How to Play Beirut (2009), in which a game of beer pong—named after the Lebanese city by an American fraternity—is played on a map of that city. “I grew up with people saying Beirut is the Paris of the Middle East. Or the Switzerland of whatever. All these romantic things. Then I step outside and to other people it’s a fucking drinking game.”

Across the room is Steel Rings, what one might call an extract from Tabet’s epic series The Shortest Distance Between Two Points (2007–ongoing). It explores the history of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline, which took oil by land from Saudi Arabia to Lebanon between 1950 and 1983, the year of the artist’s birth. “It’s the reason Lebanon was so wealthy during the pre-war period,” Tabet says. “At some point it was the world’s longest pipeline. But very quickly this desert landscape, which was supposedly safe and not political, became politicized. So the pipeline had to deal with the geopolitical transformation of the region.” Individual parts of the project have been exhibited from New York to the UAE, and are secreted in collections all over the world. In each instance the rings are one metre apart, the same diameter and thickness of the original pipeline, and made from the same steel. The “ultimate edition” could potentially be 1213 pieces, corresponding to the 1213 kilometres of pipeline. But reproducing the whole length would depend on where else he is invited to show sections.

The rings cross through the glass barrier from the gallery to its garden outside, and it seems to me as if the work’s installation enacts the original purpose and capability of the pipeline which crossed borders (Saudi, Jordan, Syria, Golan, Lebanon) which are now subject to more territorial protection and definition. The metal on the windows appears the same colour as the steel of the work, so the sculpture seems to be part of the building, or at least integrated with its architecture.

“I always say I’m the lovechild of my grandma in the village and Richard Serra”

Tabet came of age during the reconstruction period in Beirut after the Civil War, and has spoken about the aesthetic pleasure he found in isolated, fragmented pieces of building work around the bombed-out city. I wonder to what extent this experience formed his aesthetic philosophy, or made him directly interested in architecture and the making of physical things. “The city centre became a building site that was only open on Sundays. I remember going round with my parents. For them, they were looking at the wreckage of their city. For me, it was the first time I’d seen it. And since I didn’t have a frame of reference for what it was I was looking at… I’d see a Roman bath, a mosque, a church or a fragment of a modernist building, and they were all kind of the same, because they had all suffered the same event.”

The entire top floor of Parasol unit is given over to Colosse Aux Pieds d’Argile (2015): what looks like an archaeologist’s dig site of an ancient square, ruins laid out on a grid, is in fact salvaged sections of marble pillars from a demolished nineteenth-century Lebanese villa—themselves a non-indigenous European import, Tabet tells me—existing non-hierarchically alongside concrete core samples from recent architecture. For him, there is no qualitative difference between one of these villas, which would have looked as alien to the Lebanese a hundred years before as skyscrapers did later, and the rest of the city. They should all be salvaged or protected. “Beirut after the war was a city without people, so it was pure form. The war was devastating, but on top of that it had a formal result, which whether we like it or not is there. There is this question about the generative power of destruction.”

Does he find that difficult?

“What, to say that?” he quickly responds.

No. Rather, is it difficult having his art engage with this generative potential, and having his artistic eye formed by it, despite the emotional weight of the destruction? “Sure. Some of my pieces might seem hard for that reason, or heartless. I think the installation upstairs can be heartless. Like, it’s telling you to let go of the romanticism of your history. When I’m making an installation like that I have to tell myself not to feel anything. Don’t feel for these things.” For all this, my experience of Tabet’s works is that they can’t help but be soulful. What he describes as “heartless” seems in fact to be an abnegation of soul for which a great cost has been paid. Is there something he’s holding back when doing that?

“Always. If I walk through life carrying these guys around”—he gestures to the oars, and to a framed front page of the New York Times which he happened upon in the US, depicting rubble being carted away from his city —”I’d go insane. But if I walk through life with the Steel Rings, I’d also go nuts. I always say I’m the lovechild of my grandma in the village and Richard Serra. Sometimes form takes over, sometimes content takes over. But I’m conscious that I’m equal parts both. This show is making me confront different attitudes. Because certain times, I’m only that.” He points to the oars again, the paper. “And then sometimes I’m just this.” He points to the rings. “Right at this moment, I have both in my field of vision.”