I’ve just watched a man wrap himself, naked, in a plastic bag, and be buried in the ground. The surrounding scene is pastoral and the naked man looks happy because, despite being wrapped in plastic and buried, he is free.

The plastic bag burial is flickering on a screen at OTA Fine Arts in Tokyo, where an exhibition on Yutaka Matsuzawa is currently being held. It’s a grainy documentation of a ‘free art’ work, performed by Matsuzawa in the 1970s. He was an artist who was not ahead of his time, but outside of time completely.

Matsuzawa is known—or perhaps not known to most—as the founding father of Japanese Conceptualism. At this rare exhibition on Matsuzawa—because he didn’t really believe in creating physical artworks—curated by Yoshiko Shimada, were some insights into this intriguing artist, who was a rational man by day, a trained architect, devoted maths teacher, and at the same time, practicing what was perhaps the most radical art form of the 1970s, setting up a free commune in Suwa, where rituals, performances and meditation took place, and later getting into esoteric Buddhism. He was part of the anti-art, anti-conformism taking place around the world in the late 1960s, and later represented Japan at the Venice Biennale in 1976, but today, his name isn’t heard often. His work, as William Marrotti writes, “poses a challenge at virtually every level” and was so radical at a time, he was even thought to be running a cult.

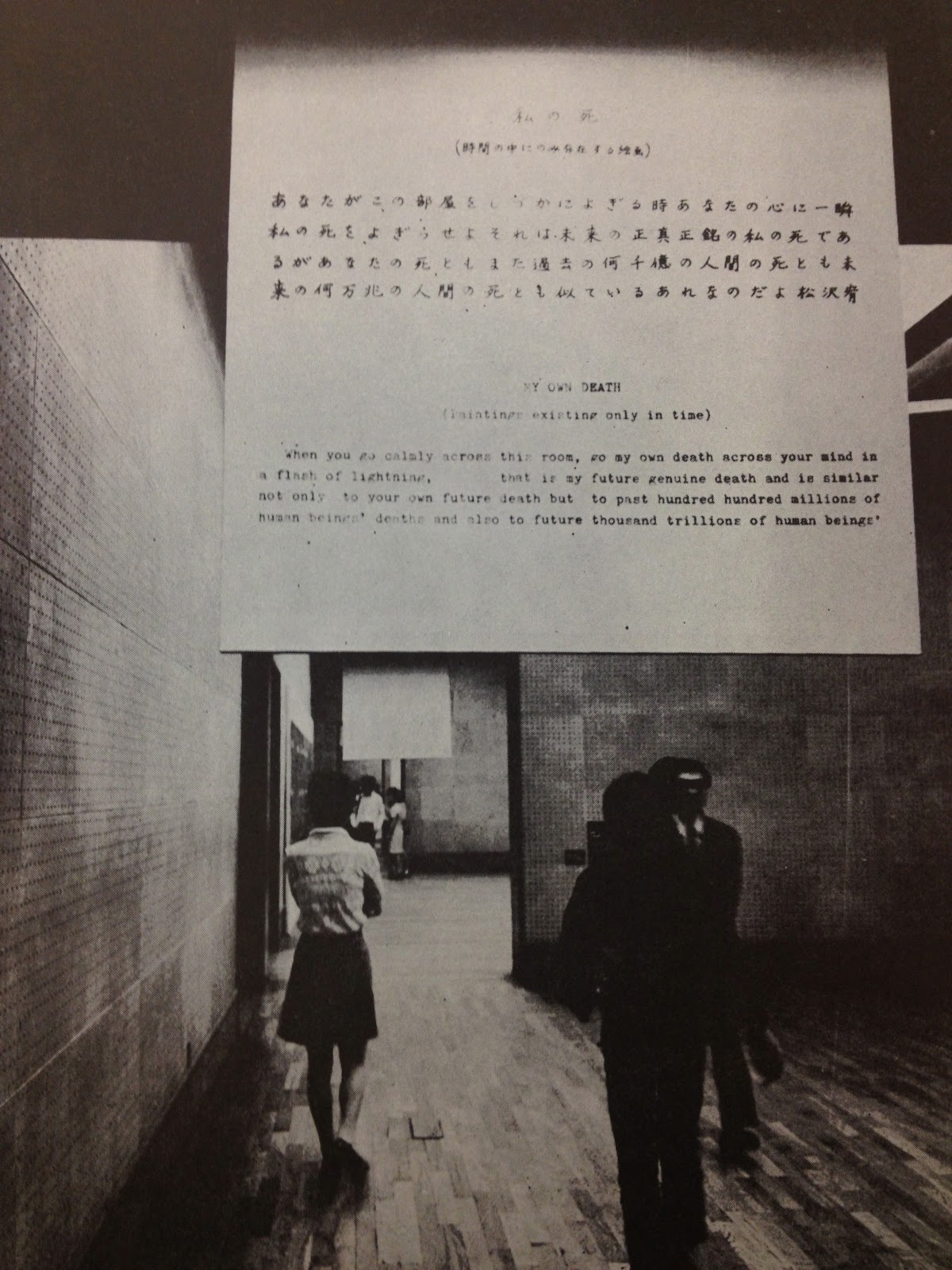

Much of Matsuzawa’s work is not visible or tangible—the current exhibit is based around letters, featuring correspondence with artists like John Baldessari (who affectionately addresses “dear Yuk Yuk” in a personal letter), photographs of performances (with more nudity, of course), leaflets and ephemeral materials for imaginary shows. And a lot of it is simply not understandable, at least, not to the ordinary human mind. But Matsuzawa’s practice explores what it means to be radical, to truly live your art, to create spaces that don’t exist: art that is truly transformative. There are moments where his ideas rip to the core of things with astonishing clarity. Matsuzawa writes: “Humanity is being challenged by numerous invisible things. We must learn to see the invisible.”

Here are some of the things we could learn from Matsuzawa’s idiosyncratic, eccentric form of conceptual art. I’m off to find a plot of land where I can roam naked—perhaps I’ll skip self-burial though.

Create a Sacred Space for Yourself

Matsuzawa had an attic room, that was known as the “psi room”, a sacred space, stuffed, according to accounts, with all kinds of strange things like old utensils, empty boxes and animal skeletons. Some guests were too scared to go up there, including a well-known Japanese poet and art critic who visited in 1963. Gilbert and George also paid a visit, in 1975, and Matsuzawa documented it on film.

Get Rid of All Objects

It might seem to contradict his secret stash in the attic, but at midnight on 1 June 1964, Matsuzawa was struck by an epiphany: he would renounce all material objects from his art, that moment forth, abandoning painting for works based around language and exchange. This would evolve into his idea of ‘final art’, allowing him to escape the white cube and move into the wilderness. He had been ruminating about the idea of dematerialization since 1946 when he graduated from the prestigious Waseda University, Tokyo, saying: “All manmade objects will eventually disappear, and so will human beings…”

Try to Solve Problems on a Postcard

In 1968, Matsuzawa embarked on his 1010 Questionnaire project, and sent a postcard to friends, with ‘8 Conditions for World Peace’, requesting of its recipients to send back a reply. Ten of the postcards Matsuzawa received back were found at his house. This was not simply an early example of mail art—Matsuzawa was interested in was the exchange of ideas, not aesthetics, the veins of communication as art in and of themselves.

Free Art

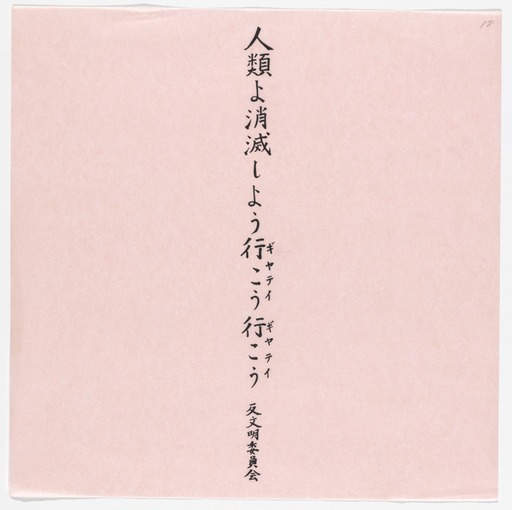

Matsuzawa received various premonitions and one of them was about ‘free art’, the criteria for which he then outlined in a leaflet he published. Loosely, free art is art that is free from regulations and prohibitions, that is without discrimination, that doesn’t bear the artist’s name or title and that is “neither good or bad, long or short, male or female, come or go, self or other, upside or downside, sea or mountain, beginning or end.”

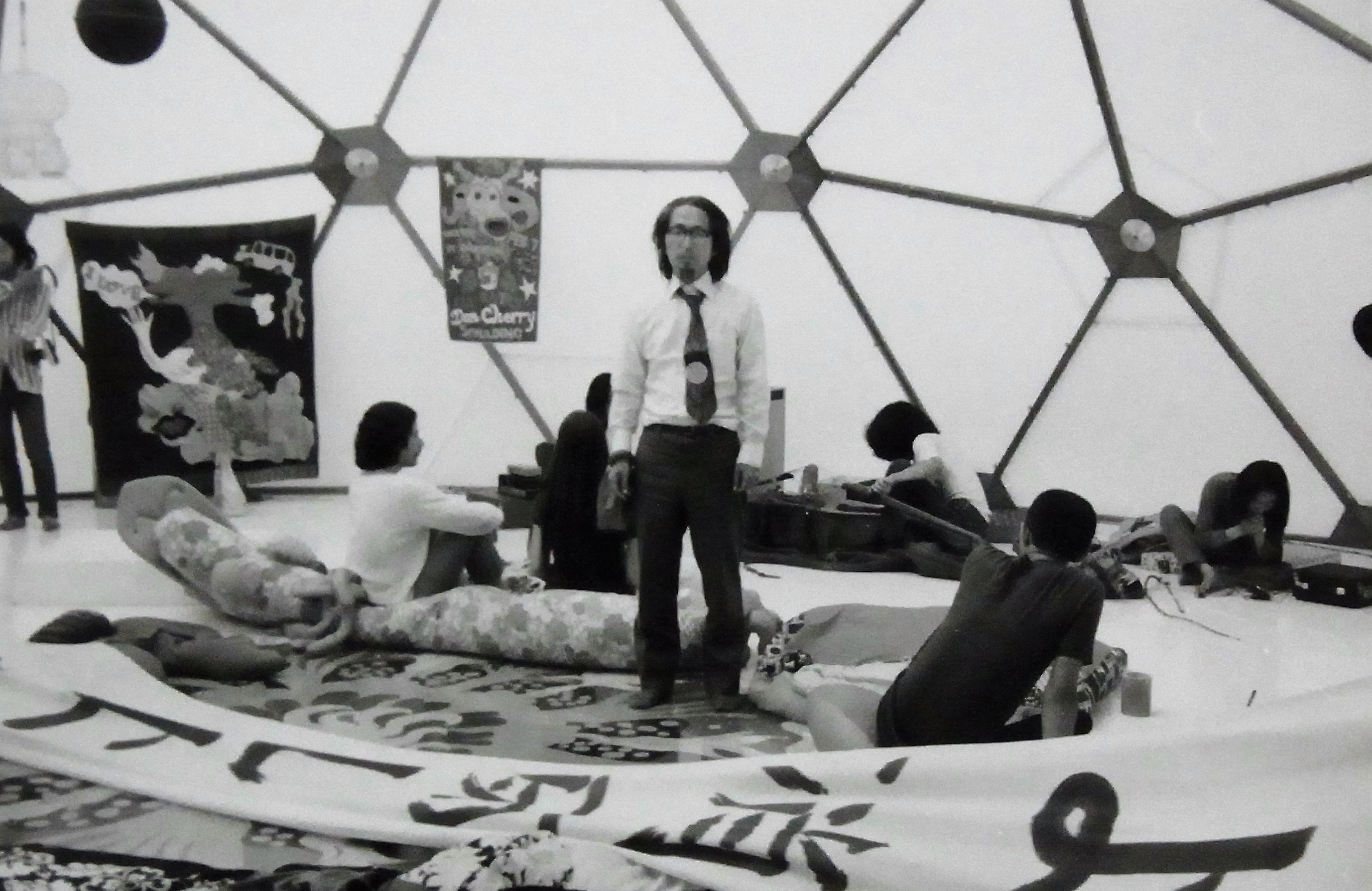

Start a Commune in the Countryside

After a legendary exhibition titled Nirvana, Matsuzawa started the Nirvana commune in Suwa, Nagano Prefecture. In many ways, it was the realization of an art utopia: open to all, clothes optional, ideas welcome. At the commune were various organisations, such as the Imaginary Space Situation Research Centre, and the Ancient Pan-Ritual Group, activities run by members of the commune, and events took place there, like a ‘concert in darkness’, where 35 guests made sounds and actions. They also made a TV programme about the relationship to snow. The commune ran until 1975 but eventually disbanded. Its ideology lives on.

Don’t Expect Anyone to Understand

Though his work was included in exhibits around the world—including Tate Modern’s 2001 Century City—up until his death in 2006, his work is still marginal and peripheral in the context of contemporary art, and it’s hard to find any artists who have followed in his path.

In his halcyon days, he was in contact with John Baldessari, Gilbert & George, Daniel Buren, Lawrence Weiner and Stanley Brouwn, as well as a network of conceptual artists in Japan during radical political and social times that have perhaps since disappeared forever. But Matsuzawa didn’t expect to be understood, nor was that his aim. Art can be a slow trickle, revealing itself only through generations of living, breathing, beings.

‘From Nirvana to Catastrophe: Matsuzawa Yutaka and his ‘Commune in Imaginary Space’’ runs until 22 April at OTA Fine Arts, Tokyo