At school it wasn’t hard to tell the artists from the geographers. On one side: flamboyant charity shop finds, impractical footwear, heavy eyeliner, emotional haemophilia, and willingness to engage with the great outdoors only for the time it took to inhale a cigarette. On the other: performance fabrics, practical footwear, map-reading skills and a nascent interest in thermos flasks.

Fast forward some decades, and all that lay between us has eroded down to so much fine silt. The artworld has taken a geological turn. At Frieze Masters the growing class of geo collectibles included fossils, tektites and even a metal doghouse with a meteorite hole in the roof. Frieze London was littered with lumps of rock including obsidian carved by Julian Charrière, Daniel Arsham’s techno fossils, and Liz Larner’s ceramic sculptures with large crystals coruscating from the glaze.

In the sculpture park, Ugo Rondinone paid tribute to rocks with his bronze Yellow Blue Monk, while Alicja Kwade – an artist who has long pondered the nature of matter and laws of the universe – offered a clear view through a lump of pierced granite.

Stone is one of our earliest materials: soft portable rocks gouged by pieces of horn or shell, and cave walls patterned with ground ochre, fat, and charcoal. What has shifted is the way artists are engaging with the specifics and origins of materials themselves. Stones evoke the imponderables of time and space.

The exploration of the ground beneath our feet speaks of the particularities of home, migration and colonial exploitation, while mineral surveys and mining offer visible evidence of the environmental impact of extractive practices. The influence of underlying geology on all living things reminds us that the mineral world is not inert but vibrant.

“The exploration of the ground beneath our feet speaks of the particularities of home, migration and colonial exploitation”

Two years ago, curator Sophie J Williamson launched Undead Matter a multi-platform project exploring death and deep time. Williamson finds geological thinking allows her to take the long view. “When we think about the precarious future of our planet it easily becomes overwhelming,” she told me.

Through a series of podcasts and digital commissions, Williamson has collaborated with artists including Oreet Ashery, Appau Jnr Boakye-Yiadom, Bo Choy and Shezad Dawood, as well as scientists, indigenous elders and death doulas. “I wanted to find a way to reach down into a deeper time frame to find some stability beyond the Anthropocene and beyond our species’ lifespan,” says Williamson. “A way of feeling a kinship with the geological underlands that have created our contemporary ecologies and with which we must nurture a caring, collaborative and compassionate future.”

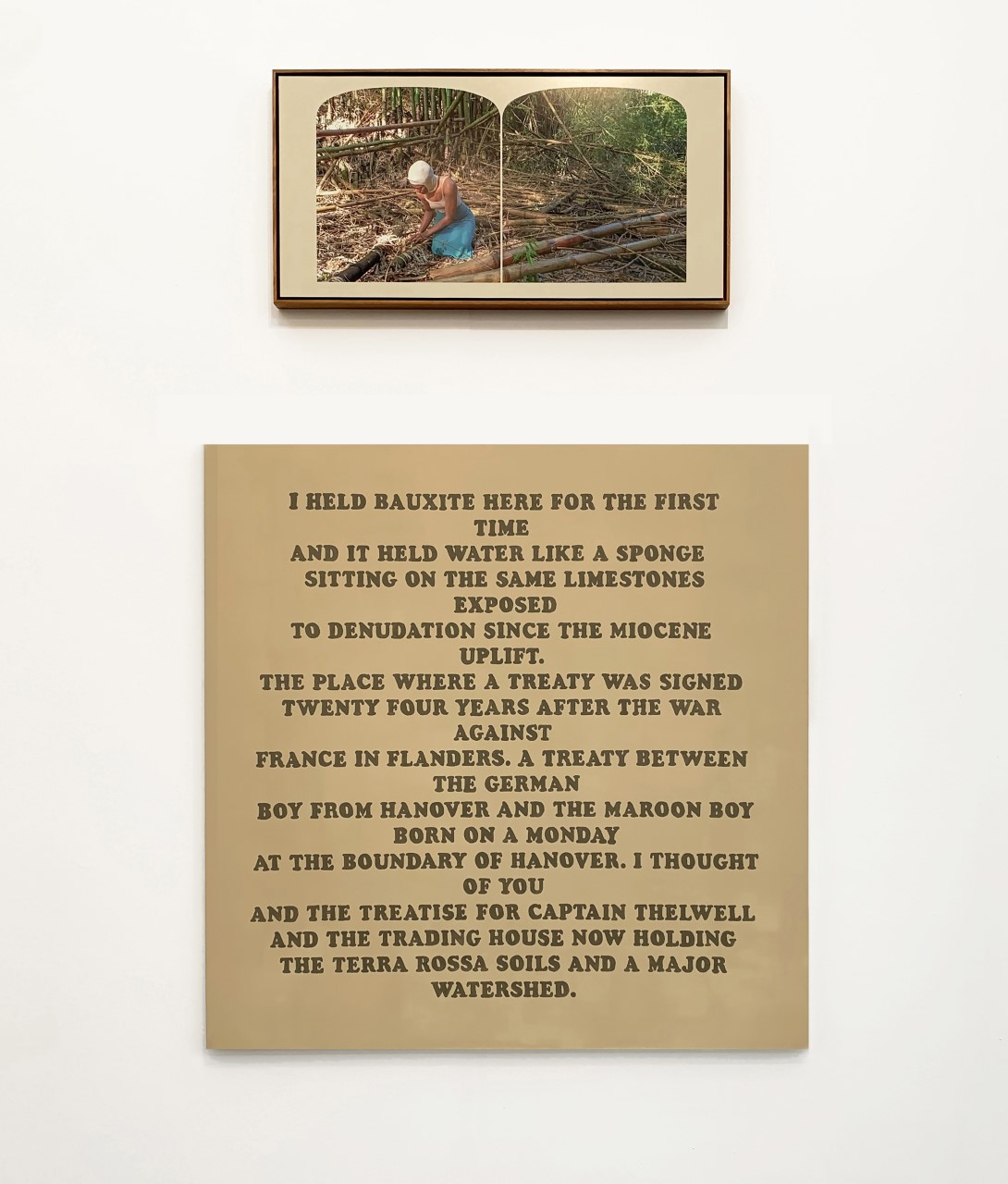

Jamilah Sabur’s recent work concerns the exploitation of bauxite – an ore of aluminium – in Cockpit Country, Jamaica. In her diptych After mining the soil is less capable of retaining water (2022) Sabur pairs a photograph of herself sitting within a lush forest landscape with a text painting describing the texture of bauxite – “it held water like a sponge…” – and the historic treatise giving control of the territory to formerly enslaved people. This is territory over which the Maroons and their descendants were supposedly given sovereignty by the British colonial administration of Jamaica in 1738. Sabur sees multinational corporations’ mining interests in Cockpit Country as a re-colonisation: people and land exploited once more, with the profits from mineral wealth siphoned offshore.

“A geological survey is not a neutral thing: it serves the interest of those with the wherewithal to dig, sell and distribute”

Other text paintings quote from a geological survey of Jamaica drawn up during the 1950s. These close observations of the mineral landscape read like experimental poetry, but convey essential information for international mining corporations: extractive industries that will go on to poison water supplies and damage Jamaica’s rain forest. A geological survey is not a neutral thing: it serves the interest of those with the wherewithal to dig, sell and distribute.

“In my practice I’ve always examined the body’s relationship to space,” Sabur tells me. “Geology is expansive and intimate. It’s so deeply embodied for me.” This is not science in the abstract: it is a route to understanding phenomena that have an impact on our everyday. Citing childhood memories, such as saltwater “intruding the very shallow, porous karst aquifer in Miami after hurricanes, contaminating the drinking water” Sabur considers her “explicit geological language [as] a way of pushing for an interplanetary, transnational discourse.”

Shown earlier this year at Bristol’s Spike Island, and currently at Vardaxoglou gallery in London, Tanoa Sasraku’s abraded and ancient-looking Terratypes are, collectively, a portrait of the British landscape painted in materials found at “points of emotional resonance” for the artist. They are like an arty, soulful set of Ordnance Survey maps. Sasraku forages minerals, rubbing strongly pigmented subterranean stuff into sheets of blank newsprint which are stitched together and rubbed and ripped to expose the layers beneath.

“Mineral pigments – as opposed to those leached from plants – are steadfast in their chromatic potency, having materialised under the earth over hundreds of millions of years,” Sasraku tells me. Minerals have long been ground for paint – this is a self-portrait of the landscape, “from deep red iron oxide stones foraged from the hills on Skye, to a prehistoric carbonised fern tree, revealed as a matte blue-black clay in an eroded North Devon beach cliff.” The series is, she says “at once a mineral record of a place, and a gestural document of my emotional state at the point of tearing.”

The rocks beneath the British landscape are remarkably diverse, from the 3 billion-ish year old gneiss of Lewis in north-west Scotland to the comparatively youthful (c6-million-year-old) chalk of south-east England. In colour, the Terratypesexpress geological diversity, while the stitching and fringing employed by Sasraku in finishing the works express links to the textile heritage of both Ghana and Scotland.

Earlier this year, I stood under the glass cupola of the Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh and poured a glass vial of very, very, very old dust into an urn. A slim shelf circling the gallery wall carried a row of 364 identical vials each holding a different material donated by laboratories, archives and activist groups around the world. Arranged chronologically, they represented over 4.6 billion years of history, from presolar meteorite dust to substances – including chemical fertiliser, microplastics and concrete – that will endure as the fossil legacy of the anthropocene. This was Katie Paterson’s Requiem– a funeral urn for planet Earth, imagined as a participatory spectacle.

For the companion work Ending, Paterson crushed 100 stony substances representing the whole spectrum of Earth history into powder, which she painted in a dial. “I believe it’s more important than ever to have an awareness of deep time to situate ourselves in a wider time horizon,” Paterson has said, hoping that Requiem will be read as “a creative response to the destruction of life and nature that’s all around us.”

Hettie Judah is a freelance writer, art critic and journalist. Her new book, Lapidarium: the Secret Lives of Stones is published by John Murray