Which are the parts of our lives that we choose to share with our parents or guardians? For most people, these details will be the commonplace and banal: assurances of good health and diet, of changes in the weather, or new developments at work or at home.

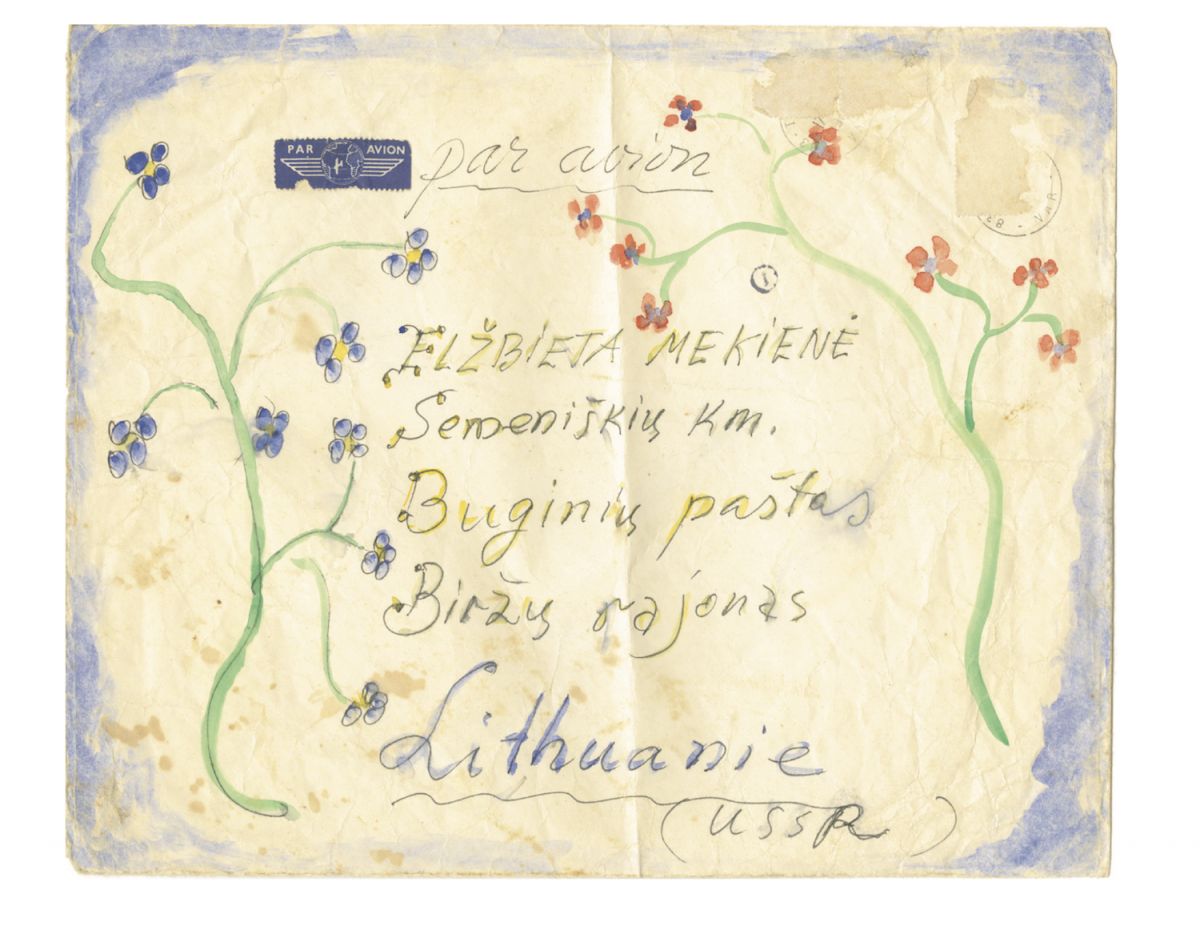

Their sheer ordinariness, the very texture of our everyday experiences, are there to reassure the receiver that all is as it should be. Letters Home, a beautiful new book of correspondence from the experimental film icons Jonas and Adolfas Mekas to their mother, Elžbieta Mekienė, shows that even countercultural legends have to write home every once in a while.

The Mekas brothers were integral figures in New York’s burgeoning alternative film culture, fervently advocating for a new kind of cinema. Their vision was for a film industry liberated from the puritanism of censorship and the creative limitations of existing industrial systems.

They not only shaped but helped to create an environment in which independent film culture could be appreciated and understood. This was an exhaustive life’s work enacted through multiple channels but predominantly writing, distribution and production. They helped set up several critical film institutions within the city, including Anthology Film Archives and the Film-makers’ Cooperative. They were writers and artists, poets on the page, and rarely seen without their Bolex motion picture cameras.

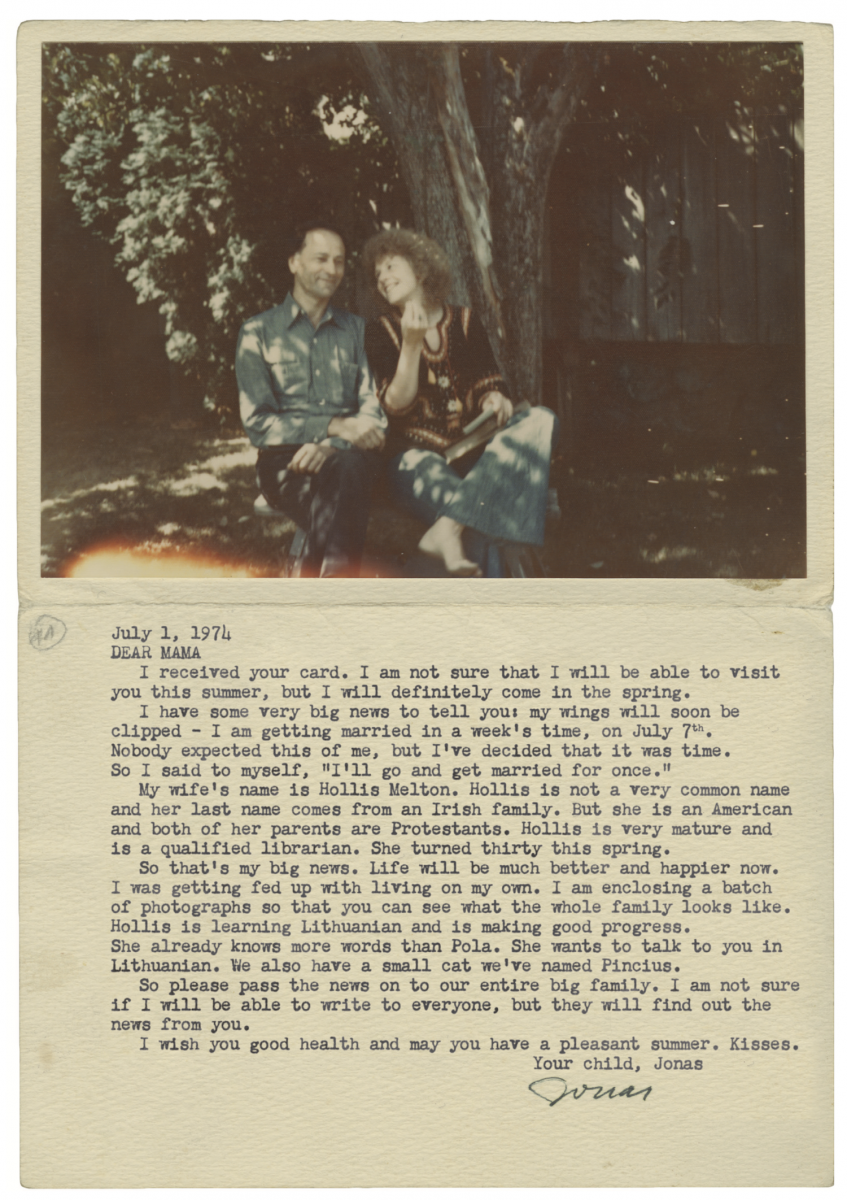

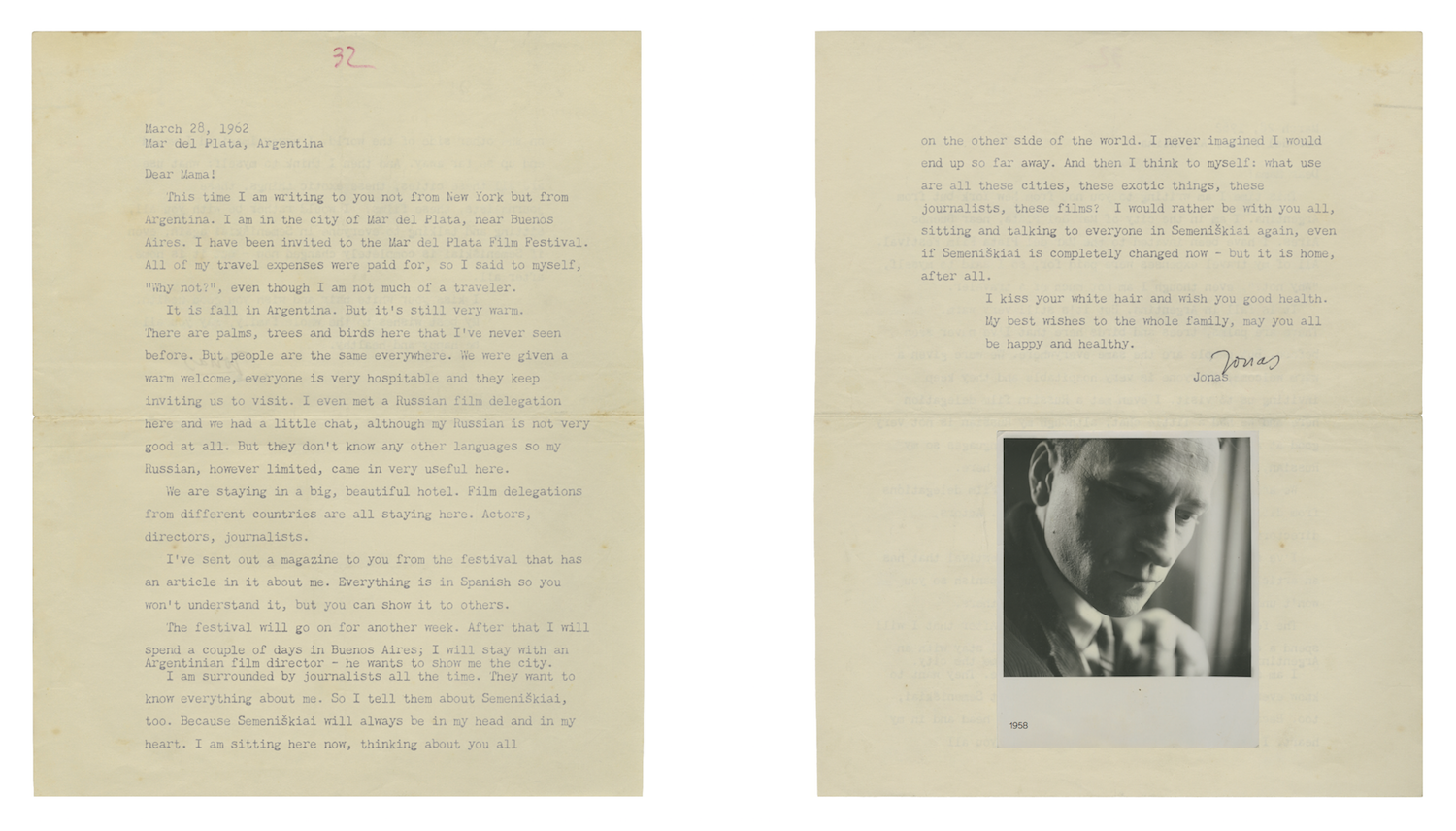

Written between 1957 and 1995, the letters chosen for this book document their displacement from rural Lithuania by World War II, their arrival in America and various creative activities in the New York art world. It also touches on some of their major life events (marriages, births and extended periods of travel) but, like so much of what we choose to tell our parents, it is also mired in the mundane.

Letters Home is an unusual book. Situated somewhere between a Mekas family photo album and a treasure trove of personal letters, it neither illuminates the wider film scene in which they were such driving forces, nor does it tell us much about their lives that we didn’t already know before.

But this kind of linear biography is not truly the book’s intention. Letters Home is rather a loving tribute to a place: specifically, the village of Semeniškiai in northeastern Lithuania where the two brothers grew up.

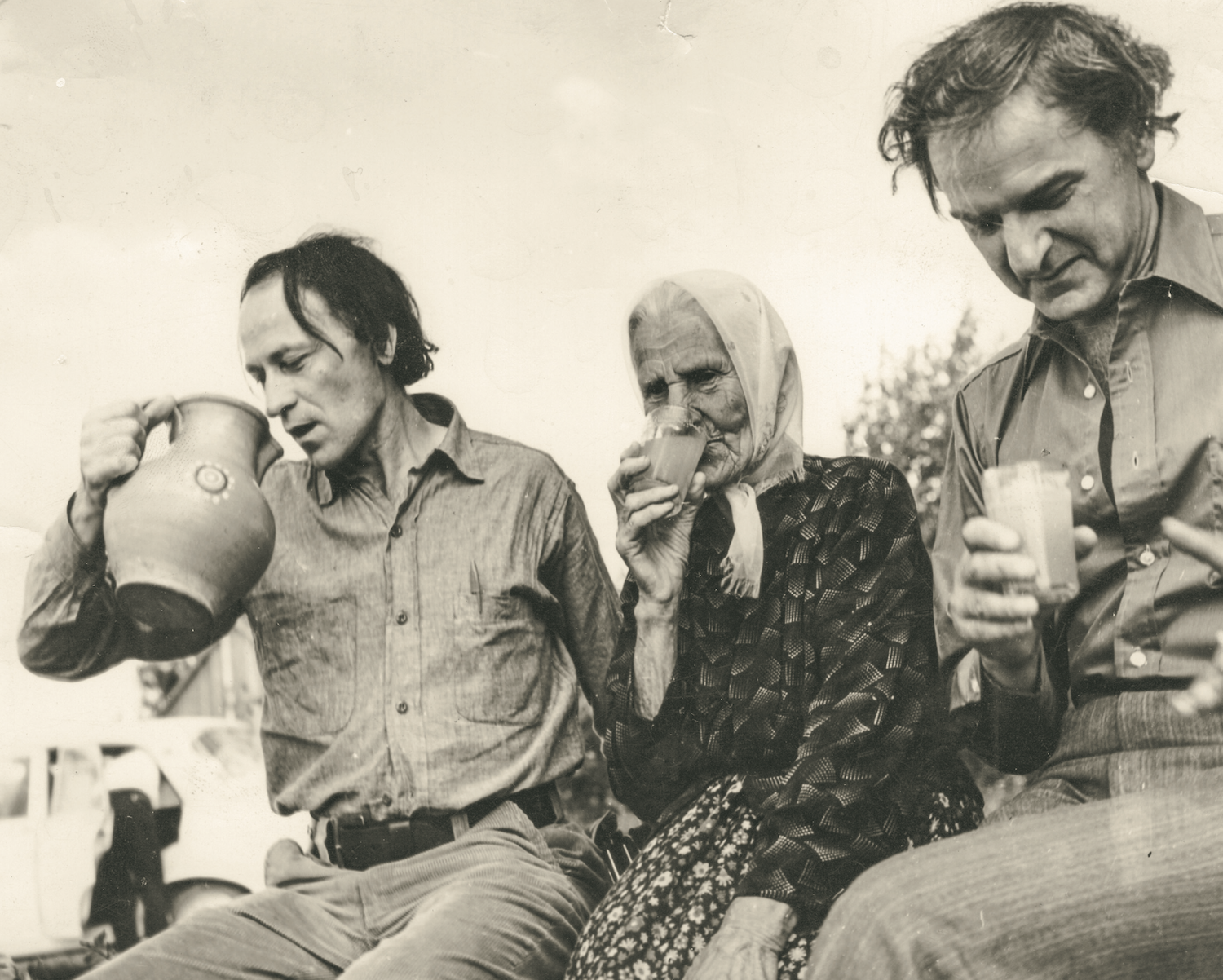

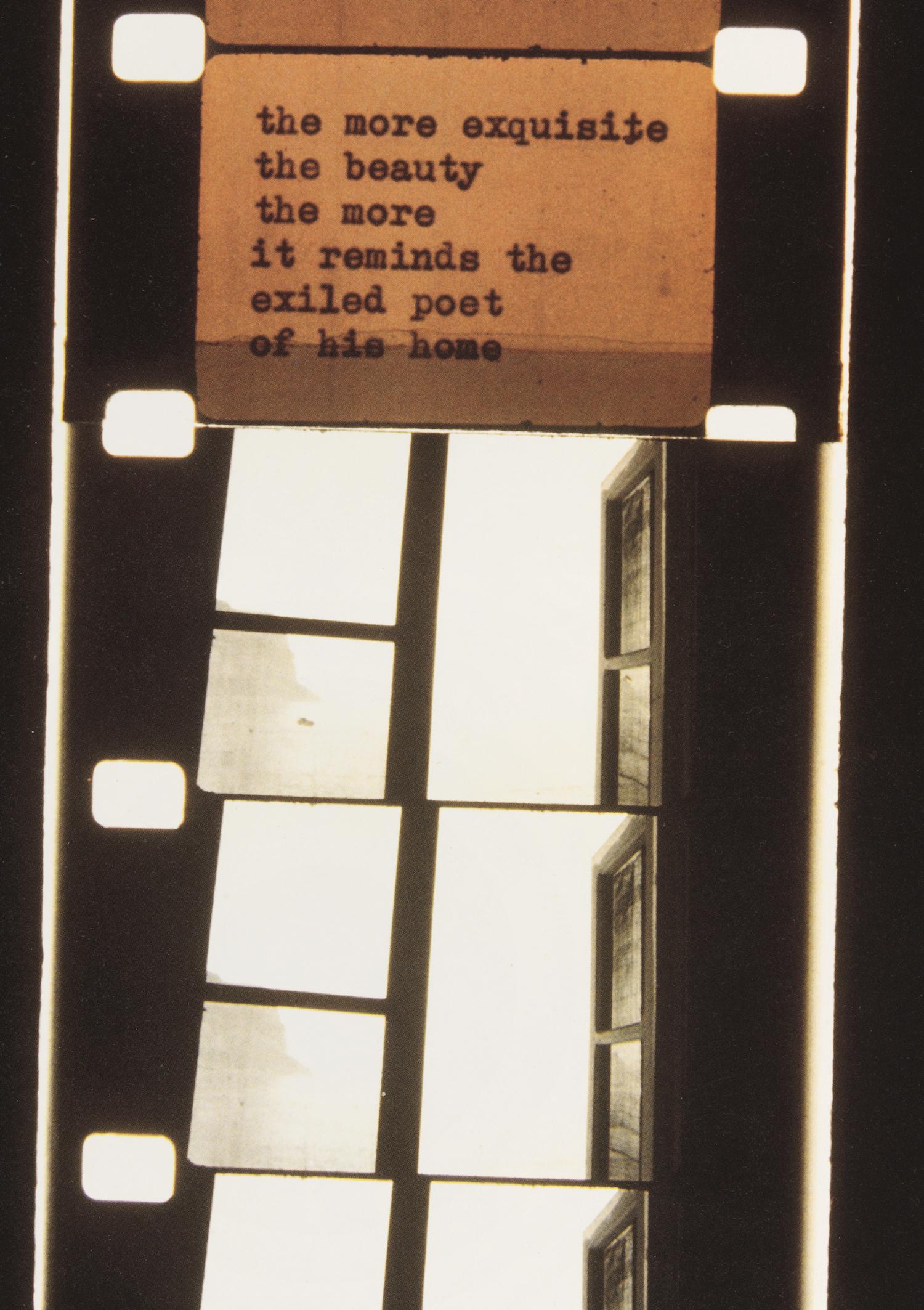

Their reminiscences of growing up on a farm, illustrated by tender, black-and-white family portraits, open a window onto agrarian life in Lithuania before and after the war. The combination of texts and images conjures up long, hot summers in a muddle of family and friends, not unlike Jonas’ kinetic, fragmented diary films, where the mythology of a pastoral idyll is a recurring obsession.

“Letters Home is a loving tribute to a place: specifically, the village in northeastern Lithuania where the two brothers grew up”

There are some very beautiful photographs of Elžbieta, a fragile yet commanding presence. One (a particular favourite) shows the brothers drinking homemade beer with their mother on a stoop. Some of these images are printed on transparencies, echoing the in-camera superimpositions of Jonas’ films.

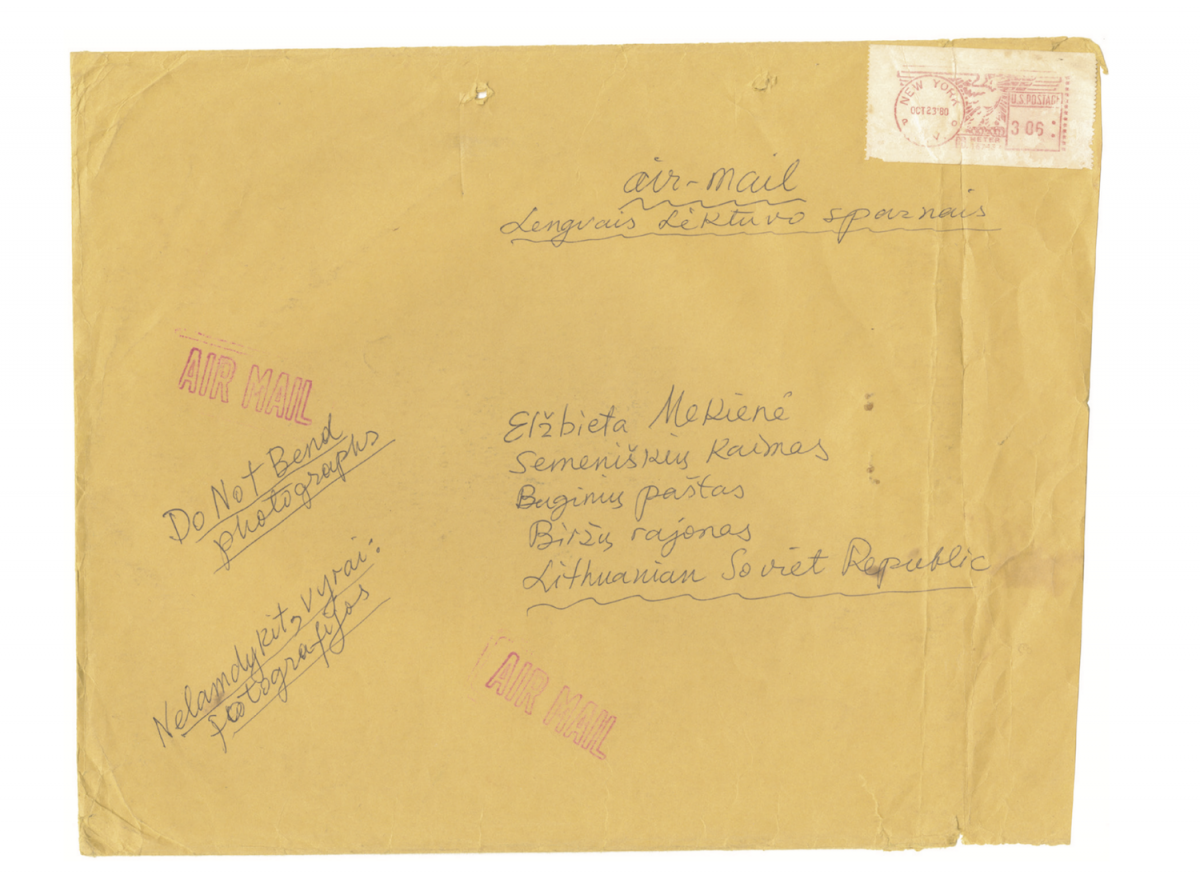

The best part of this book is how the reader is invited to engage with the physicality of letter writing. Loving recreations of family letters in it require cutting open with a traditional letter knife (although detachable perforated flaps are provided in case you’re missing the correct cutlery). Working your way through this book, prising open every other page, feels at first laborious, but soon takes on a gentle, soothing rhythm, imbued with that sense of discovery you might get in an archive or coming across unopened correspondence.

These letters piece together the shards of lives that were lived very much in the moment but were nevertheless infused with a bittersweet yearning for home. The mutability of memory and how it warps and changes over time (a key tension in Jonas’ films) is never far away.

There is a palpable glee in sharing gossip about other Lithuanian emigres or complaining about the bad cuisine in New York. Other letters seem restrained and bound by filial duty, holding back on some of the darker aspects of being poor and displaced in post-war Brooklyn.

“Loving recreations of family letters in the book require cutting open with a traditional letter knife…”

“We may not write to you often enough,” writes Jonas, “but we never forget you and think about you all the time. Our best memories are from Semeniškiai, when we were all together. But we both believe that one day we will be together again, even if it is in another life. We believe that people do not die. We believe that life on this earth is but a short moment in our whole existence. Life is only the glass which we penetrate like rays of sunlight. Rays with no beginning and no end.”

Kęstutis Pikūnas, the book’s designer, intended the experience of reading it to be an immersive one: “I wanted it to be as close as possible to a ‘film on paper’,” he explains. Later he adds, “I’m a firm believer that we don’t only read with our eyes, it’s how we touch the paper, how the sequence and narrative of the pictures introduces us to the letters and other bits and pieces within a book.”

Seen through the blinkers of a pandemic, when the majority of people (aside from the UK prime minister) have endured displacement or distance from loved ones, Letters Home takes on a particular poignancy. Though they may not be our primary mode of communication, letters attempt to bridge time and space by reaching out to another.

In many ways, that’s how Jonas Mekas’s films feel too: an intimate correspondence between filmmaker and audience, a hand reaching out through time.

Sophia Satchell-Baeza writes on films, psychedelic art, and the 1960s British counterculture