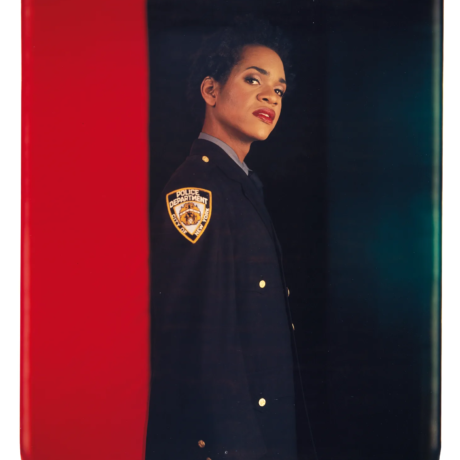

Theo Meranze speaks with painter Lewis Hammond and DJ Darren Cunningham about their relationship as cousins and collaborators.

The painter Lewis Hammond and the DJ/Producer Darren Cunningham, better known as Actress, are cousins. This may come as a surprise for some. Until this year, The Wolverhampton raised artists embarked on professionally disconnected journeys to success; the younger Hammond attending the Royal Academy Schools where he began to receive recognition for his ability to paint tranquil yet uneasy surrealistically inclined scenes, and Cunningham becoming a household name in the British electronic/ dance music world, founding the independent label Werkdiscs, signing to the iconic Ninja Tune, collaborating with the likes of Sampha and Zsella, and releasing a extensive body of work composed of a sonic palette that ranges from cavernous, ambient soundscapes to twisting beats with Detroit techno inspired dance stylings.

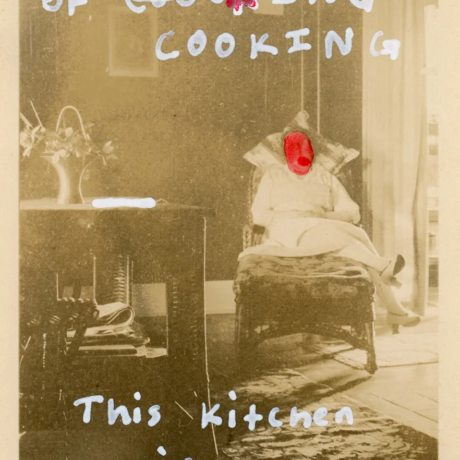

It only made sense then when the two collaborated for Hammond’s first London solo exhibition in the UK titled This Glass House, which opened in September at The Perimeter in London. In Hammond’s exhibition space the often eyeless characters of his paintings —and strikingly, the reoccurring pieces that contain collections of eyes they are interspersed with — are sonically coated by the rumbling and at times exploding waves of a soundscape composed by Cunningham. There is a subtly theological nature to the exhibition, whether that be the romantic intensity of Hammond’s scenes or the Gregorian chants that flow in and out of Cunningham’s composition. To me, it most strikingly feels like the expression of a contemporary interiority; one filled with a lust for being yet gripped by the paranoid uneasiness of life under techno-capitalism.

Over Zoom, I sat down with the cousins to explore the background of these various artistic throughlines, how they’ve influenced each other, and the importance of ambiguity in art.

TM: I’m curious how this particular collaboration occurred, and if you have a history of collaboration? Have you worked together in this capacity before?

LH: So there were a few false starts over the past few years. There were people in the art world who were aware that we’re related, huge fans of Darren’s work, interested in what I was doing, and were looking for a way to get us to work together. It’s interesting and sort of special because we’re both from Wolverhampton, which isn’t necessarily an arts center or a cultural center compared to places like London, New York, or Paris. But basically because of our schedules and the lead time on some of these projects we weren’t able to get the momentum to do anything like that. But then this opportunity came up with the show. The show in London has two iterations, the first in Germany and the second in London. I think I was about halfway through the show in Germany when I started to speak to Darren about collaborating on a sound work that could emanate through the space in London. I suppose we just chatted: text messages, phone calls, sharing inspiration. I’m fortunate enough to have access to Darren’s music output as well. I know what he can do and what he can bring. So I guess this is the first time we’ve officially collaborated.

TM: I assume that despite this being your first official collaboration that you guys have been communicating about your respective practices/work for sometime? Would this be a correct assumption?

DC: I think there’s a conversation all the time, whether it’s direct or not. I mean we’re blood cousins, I’ve known Lewis since he was small: we grew up together. So there’s obviously some sort of shared consciousness going on there. When I look at his images in many ways it seems quite familiar.

LH: It’s funny, Darren you may not recall this, but I remember being fifteen or sixteen and Darren describing to me what music-making was at his parents house. At the time I was playing in punk bands and hardcore bands, but I was also doing some solo, bedroom musical stuff. Darren’s always been there as a figure I looked up to and respected or even revered in some ways. So even if there isn’t always a direct conversation about what I’m painting right now or what project he’s making right now, there’s kind of a wider scope as to what that sharing could be. As integral as it can be for me to sit here and describe something that’s happening in my studio Darren and I also talk about, relationships, things going on in our private life. I can’t really draw a line between the two: the private and the professional world… Even more so of late as my studio and my home are within the same property.

DC: If I’m being honest, I was stunned when I first started to see the works that Lewis was coming up with. The realisation of some of the imagery just stunned me honestly. It really tapped into a voice musically for me. Lewis uses the word “calm” a lot. That’s what he was like when he was growing up, quite quiet, quite calm. But at some point there was this moment when he was skating alot. Not from my perception at least going off the tracks, but becoming sort of rebellious, discovering his identity, tapping into his identity, his heritage. And when he started to emerge at The Royal Academy I went down to see his student exhibitions and I just felt the paintings bringing me towards them. So in terms of collaborating with him at this point it’s such an honour, really. I just see such a huge potential in his style, just the work ethic is something to commend as well. I know what it takes, spending hours in the studio obsessing over a sound, trying to split a sound. So the collaboration was super easy actually. He sent me some audio recordings that were knocking around, I sent him some piano pieces that were knocking around that I thought might work. He gave me a little bit of guidance as to what he thought he wanted, and I tried to tap into the space he was going to be working in and what pictures he was going to choose, that was going to be really important to me regarding making something. And then when it all started to come in and I heard the recordings I knew instinctively what I had to do. I think that’s why it works as an exhibition. I like the idea that it (the soundscape) comes in rushes, you know, intermediate periods during the walkthrough.

LH: To return to one of your preliminary questions about parallels between our practices, I work with a lot of collage, especially when building imagery for my paintings, and that’s how I hear a lot of Darren’s music. I hear chops from Detroit, or a sort of kind of memory of being in smaller clubs and venues and hearing a specific kind of sound, whether that’s garage or techno. So this kind of idea of borrowing or paying homage or even showing reverence / irreverence is how we both kind of work. For me it’s old master paintings or proto-renaissance paintings. For Darren it may be Detroit techno or something, but we take those influences and bring them into what we’re doing now, and I think that we’re both producing things that are reflective of our current moment.

TM: Could you guys talk a bit about the psycho-social aspect of what you’re meditating on in the work? There’s definitely this beautiful, as you said, “calm” kind of serenity to the work, yet there’s also an uneasiness. Like in your soundscape Darren, after getting to listen to it, I really appreciated how there are these theological, vocal-esque sounds within the mix, but they’re coming up and down like a wave and are being covered up by this static and this continuous kind of hum.

LH: I loved that section as well.

TM: I love that section too. I think in a way too it gets at a deeply human, metaphysical aspect of a society that can often feel so synthetic. So to reiterate, I’m curious what you’re getting at psycho-socially and sociopolitically with the work. Because it really comes through without being too didactic.

DC: Did you say theological?

TM: Yeah.

DC: Well we both went to Church of England schools. We don’t come from an overly religious family but religion was present.

LH: Yeah, it wasn’t overbearing but we would go to church together. It was a part of our environment.

DC: We come from Jamaican heritage on one side and then there’s the Church of England side, which is the school side where you’re going in and doing eucharist. So for me there’s this juxtaposition of going to a Church of England school and doing all of its customs, but then also being a little bit on the other side of it. This sort of contrast of dark and good and evil, and what that is, having to study that: drinking blood, the body of Christ, and then smoking weed. Also being from the midlands, not from the hustle and bustle of a big city. There’s this sort of space. I mean I took it up by constantly practising football or listening to music. Maybe at the time not making music so much, but gaming, writing programs. A town like Wolvererhampton demands that you have something or a hobby to take up that space. Because it’s got country aspects, it creates this sort of channel where it’s quite cerebral and quite ambient. It leaves openings for contemplation.

LH: Darren and I were talking at the pub after we had the photoshoot for this piece last week, and I was saying how I always struggled to articulate the importance of growing up in Wolverhampton to my work, because it’s a very particular place: it’s kind of a buzzword, but the hauntalogy of it. Warberhampton has these canal routes, which are obviously a fossil of industry: there are still coal mines there. That’s why Wolverhampton is called “the black country.” It’s got such a particular kind of psychology, it’s not specifically suburbia, but there’s an uncanny or kind of hidden nature to the place. I think that’ll stay with me for the rest of my life, and I see and feel it in both of our practices.

DC: To get at the particularly socio political aspect of your question, Wolverhampton is also very deprived in many areas. There are drug issues relating to disconnected families, issues related to money in the education system. Musically the way that I report on it, because I’ve spent an equal amount of time between my hometown Wolverhampton and South London, Brixton, a lot of my work, particularly Ghettoville, was about collapsing the pallet to represent a sort of collapsing of society and communities in this dystopian world. And then R.I.P. again is another juxtaposition of the hypocrisies of theological practices but also my dedication to them as well. I think with art you’re able to express these confusions or these non-answers that you get all the time. Music for me gives me the possibility to answer these things that can’t be answered by society, and then there’s this sort of feedback loop by giving that back to society in a recorded format. In Lewis’s case I guess it might be the same in terms of a piece of art that could go for thousands or millions or whatever. It’s our way to communicate fundamentally. Regardless of if we’re family. It’s just interesting that we’re family. For the first time I can look at my dreams in my cousin’s pictures.

LH: Yeah. There’s also something about these concrete things that Darren’s thinking about, the disparity between rich and poor, especially as England has become more and more London-centric, this disenfranchisement that we can see in what would’ve been in our local communities. We’ve absorbed that and I suppose however ambiguously we’re kind of tying that back into our work. For me it’s often through exploring a kind of psychological interiority of the figures in the paintings. And again, it’s kind of ambiguous. There’s no pointing fingers to the collapse of local industry or anything so specific, but there’s more of a sense of deep introspection, which is a common theme in this exhibition at least. There’s something about taking something quite real, like the architecture that we observe and exist within, and channelling that. Almost all my work is figurative, a representation in some way, but it’s also an abstraction of my own experiences.

TM: I think it’s really interesting how you have a more abstract soundscape to accentuate the underlying, less didactically figurative emotional aspects of the paintings.

LH: Yeah. When Darren and I were talking about putting this all together I think I maybe said that often the exhibitions, art, film, or culture that I’m most moved by leave the door open a bit.. Posing more questions than answers. I have always found that to be more generative and generous in a way.

TM: Lewis on that note I’m curious about the eye-paintings in your exhibition. What were you channelling through those images?

LH: The eyes were this kind of returned and accumulated gaze of the eyeless figures in the paintings.But you can feel them looking, feel them seeing. So in a way their eyes have been collected into these series of smaller paintings. In Kunst Palais iteration of the show the eyes were dotted throughout, so there was this continuous thread of being watched or looking, this sense of paranoia that weaves throughout the exhibition. At least, that’s partly how I see them functioning. I live mostly in Berlin at the moment and there has been a significant increase in the arm of the state impinging on people’s lives and genuinely threatening democracy, often in service and in defence of fascist politics and imperialist ideologies. I wanted to reflect on the feeling of this increased surveillance and control. The eyes meet the gaze and also gather and grow in ways I can draw a parallel to the politics of resistance.

TM: That makes sense. Something I’ve been thinking a lot about in regards to your work and the show is our relationship to social media, this kind of constant seeing. I like that in your work I can feel this kind of constant presence of sight, these technologically panoptic aspects of our society, despite it being painting. Darren I don’t know if you were thinking about this with your piece but I can sense that in it: this kind of intensity that’s sunk into the background.

DC: I don’t really think about these types of things if I’m being honest with you. I think the information is already in the sound. So with Gregorian chanting I don’t really have to do so much with that. The expression, the channelling is already there. As an artist you’re often just a conduit for these things. You allow it to come through you. Or you could be an obstacle and make very specific decisions. Sometimes it’s kind of fifty-fifty in that respect. But the piano piece that I gave to Lewis originally had the title “Pieces of a Mother’s Man,” which to summarise is about how the people closest to us are often our mother’s, our father’s, or our grandparents. And they don’t really understand what you do. So how do you describe to someone you love that this is just me? This darkness, or what you see, or what you hear is just me: a product of what you’ve produced. One of your preliminary questions was “do you come from an artistic family?” and I don’t think that we do. But there was obviously something artistic there, in order to express our environment, or what it was that we were feeling. Everything has to do with feeling. A picture should make you feel something, or overwhelm you in some way to make you feel alive. Or music, when tied with the visual, should offer a sort of scenic narrative I guess. It shouldn’t overcome the experience. It should just be there.

LH: Yeah. I think in the show the sound and the visual coalesce in quite a harmonious way. Which is sort of surprising as well because the paintings can often be suggestive of a violent or transgressive moment; a tension between people. The symbiosis between the sound and imagery is quite evocative, I hope it can help the viewer arrive at an unexpected place. There exists a dramatic ambiguity in both what you see and hear, so that you are left sitting in the atmosphere that you arrive at within the show. I tend to think the viewer contributes if not “completes” the work, so the openness allows room for the thoughts and feelings of the audience to come to their own understanding of what they are engaging with.

Words by Theo Meranze