Fashion and portrait photographer Lia Clay Miller’s work sees her make a personal connection with her subjects in a way that feels palpable to the viewer. Often shot in black and white, with the odd pop of colour, there’s an element of quiet theatre in Miller’s photography. This is created through a series of contrasts, with dynamic poses and sometimes flamboyant styling, being offset by the locations her images are shot in, typically on the street in places Miller passes every day. “For me, my work isn’t about subverting the normative, rather creating a realm of beauty beyond subversion,” she tells me.

Based in Brooklyn, New York, Miller’s work has appeared in The New York Times, Out Magazine, The Wall Street Journal, i-D and Teen Vogue, and she’s captured the portrait of many famous faces including Hilary Clinton, Billie Porter, Fran Leibovitz and Indya Moore. Even when photographing these well-known celebrities, Miller draws out the soul of her subjects in subtle ways, presenting us with images laced with vulnerability and candidness.

As a trans woman, Miller’s personal identity has often been conflated with the work she’s creating, but she has now found a balance between wanting to tell the stories of her community and ensuring her identity doesn’t overshadow her work. Instead, she puts her energy into getting the voices of those at the back pushed to the front. “I think people underestimate the power of who is behind the lens,” she says. “There needs to be just as much representation there as in front of the camera.”

- Left: Jeremy O for Paper magazine, Right: Natasha Lyonne for Interview magazine

What first got you into photography?

My Grandmother. She had an interest in photography, and always photographed our family. My grandparents took several trips out West, and my grandmother always came back with photographs.

These were my first ideas of what a photograph was, and how it worked. I started taking photos when I was eight. It was a way to contextualise my world. I’d spend hours walking around in my grandparent’s backyard taking photos.

“There needs to be just as much representation behind the lens as there is in front of the camera”

Neve

Your work takes on many forms but it seems you’re most drawn to portraits, why do you think that is?

Early on, I had this feeling that my photographs weren’t complete unless there were people in them. As a teenager, I was really drawn to the work of Mary Ellen Mark, Nan Goldin and eventually Carrie Mae Weems. They created portraits that lived in and on with the times, and that really struck me. I try to photograph portraits as a way of communication, often they are of people that I am friends with or have some connection to.

Ultimately, all photographers are photographing from within, so there is always something in my work that is manifested from my own consciousness. I’m often conflicted when working professionally. I’ll have this idea of a way to photograph something that only makes sense in the photograph. It’s nearly impossible to explain it, but unfortunately, most editors want preconception before allowing you to take the image.

Representation is a topic many people are talking about now, but when put into action it can often fall flat and seem like box ticking or surface level engagement. How do you think the industry could do better?

I’ve been really critical of representation when it comes to the way I work and who I am working with. Mostly, I don’t see it in the image anymore. It needs to go beyond that. Who are you hiring? Who has the power behind the image? My work has had a lot to do with representation. But I try to stray from images that are forcing the representation onto the subject themselves. It needs to be a conversation with everyone involved. My job, mostly, is to make sense of all of the pieces.

What has been the most important project that you’ve worked on so far in your career?

I think it would have to be the ongoing project of trying to bring forward the voices and people that need to be seen and heard. Yes, there are jobs you do for money. But the jobs that actually matter are the ones that bring the present into perspective. It’s not lost on me that I am one of the few trans women in photography. And my contemporaries are mostly cis white men. I think people underestimate the power of who is behind the lens. There needs to be just as much representation there as there is in front of the camera.

“Yes, there are jobs you do for money. But the jobs that actually matter are the ones that bring the present into perspective”

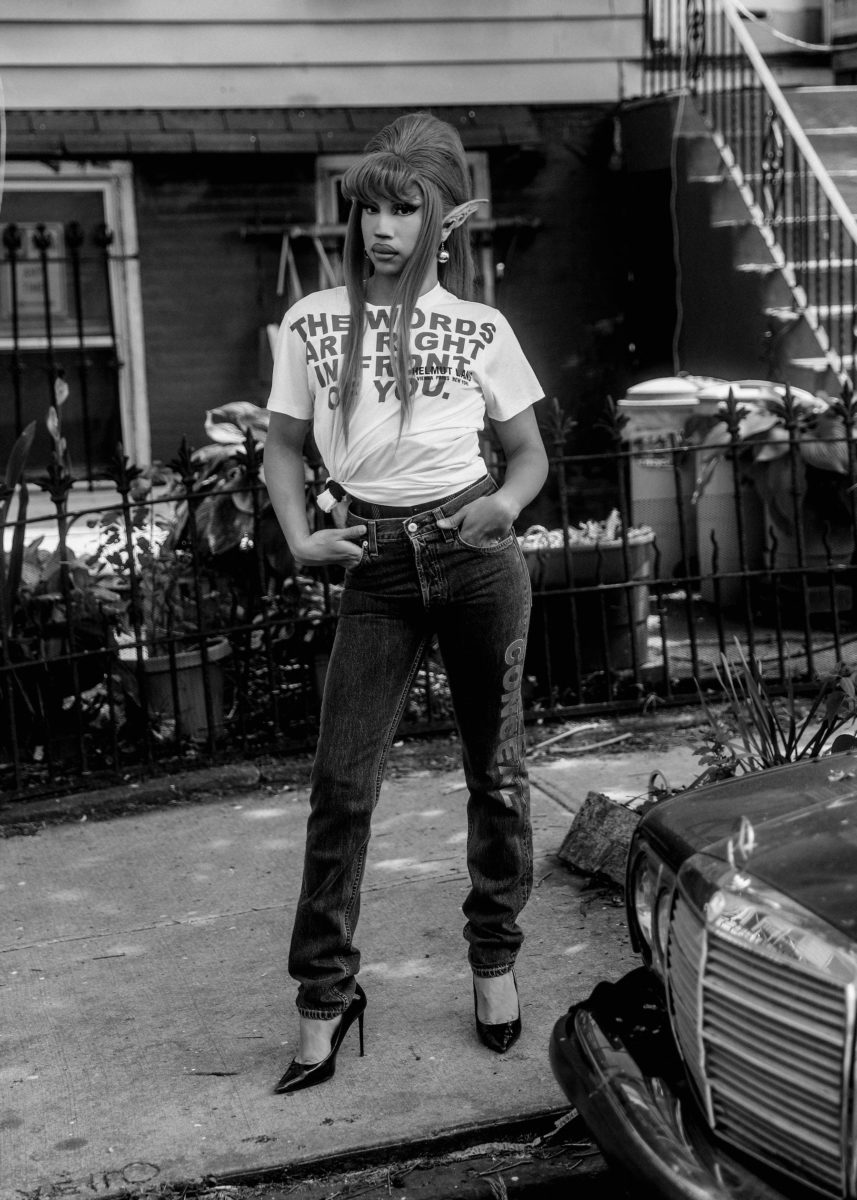

- Left: Juku for Willie Norris' Helmut Language, Right: Willie Norris' Helmut Langauge

What do you hope people feel when they see your photographs?

As a portrait and fashion photographer, there is always the push for the fantastical. A lot of my work is on the street and in places that I pass every day. For me, my work isn’t about subverting the normative, rather creating a realm of beauty beyond subversion.

A lot of my subjects, like myself, are transgender. This wasn’t something that came about because I purposefully went after photographing my community. Rather, it’s the manifestation of my world, my reality, and hopefully theirs too. I’ve said this several times, but often the lens is used as a means of voyeurism. I want to look past that, and create images that make myself and the subject feel illuminated, not deconstructed.