Since the invasion of Ukraine on 24 February, photography has been a key instrument in alerting the world to the Russian army’s killing of civilians and destruction of towns. Six weeks after the conflict began, Bosnia was commemorating 30 years since the beginning of its own bloody three-year, inter-ethnic war, part of the breakup of Yugoslavia, which killed 100,000 people and displaced more than 2 million.

In this context, American photographer Robin Graubard’s images of the siege of Sarajevo feel all too familiar to modern readers. Appearing in her debut photobook, Road to Nowhere. Eastern Europe 1992-1996, the images show bombed out streets, refugees sleeping on mattresses in sport halls, and tanks and soldiers posing with their military equipment. No longer part of a relatively distant past, the works now pervade our present moment.

“I decided to go [to Sarajevo] after meeting a group of women in a park outside the UN Building [in New York]. They were talking about how no one was covering the war in Sarajevo,” Graubard writes in the book. “As I was checking in [at the Holiday Inn in Sarajevo], a bullet passed just above my head. The man at the front desk seemed to be in some sort of trance and just ignored it. Heavy shelling went on outside my window every night. I crouched on the floor of my hotel room, thinking it would protect me from the shelling. Somehow it did.”

I visited Sarajevo last summer for its glorious film festival, which started in 1995 (the last year of the war) and has continued to grow ever since. While there, I spoke to many Bosnian artists who are still processing the experience of violence in their work, but also to others who wish to move away from it.

Some would get frustrated by how Bosnia is depicted internationally only with reference to its past war. Flicking through Graubard’s book, I recognise the streets and the tower blocks that had been bombarded and are now rebuilt and filled with life. The thought gives hope but also shows just how fragile our lives and homes are.

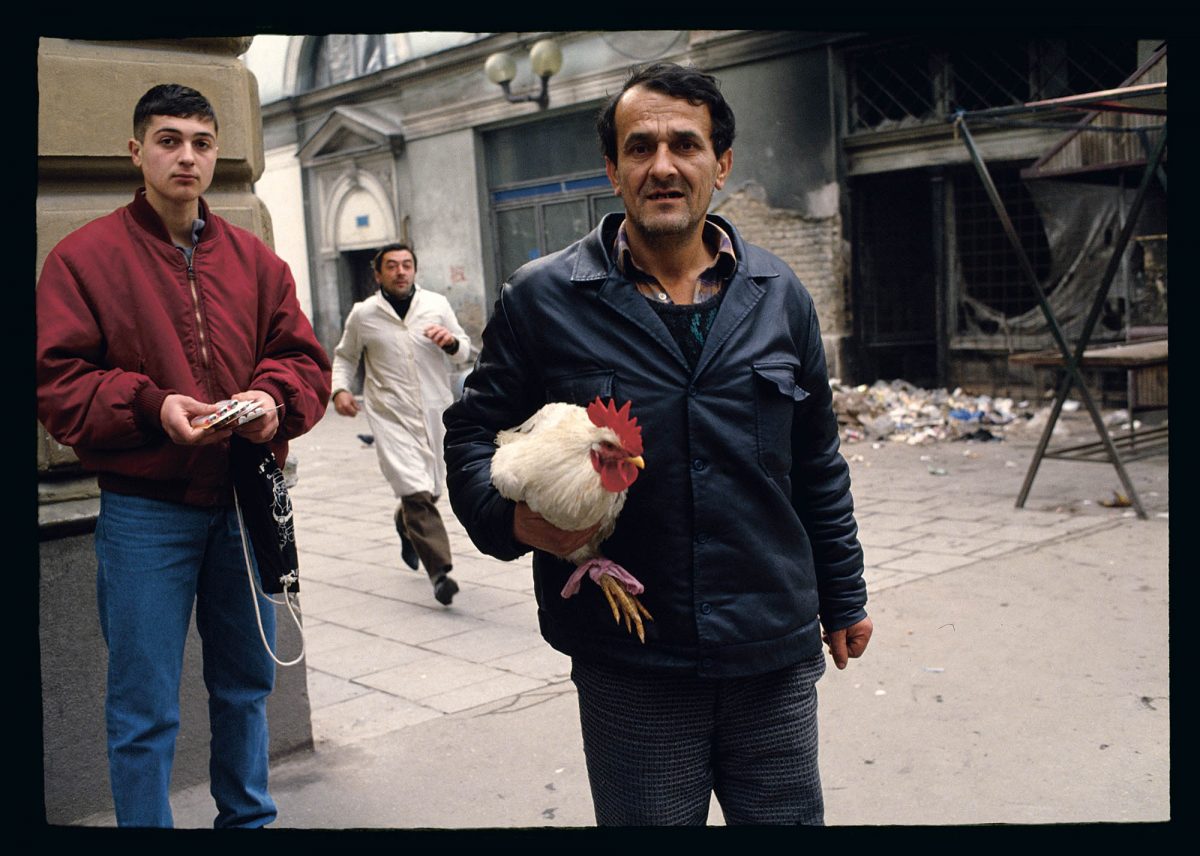

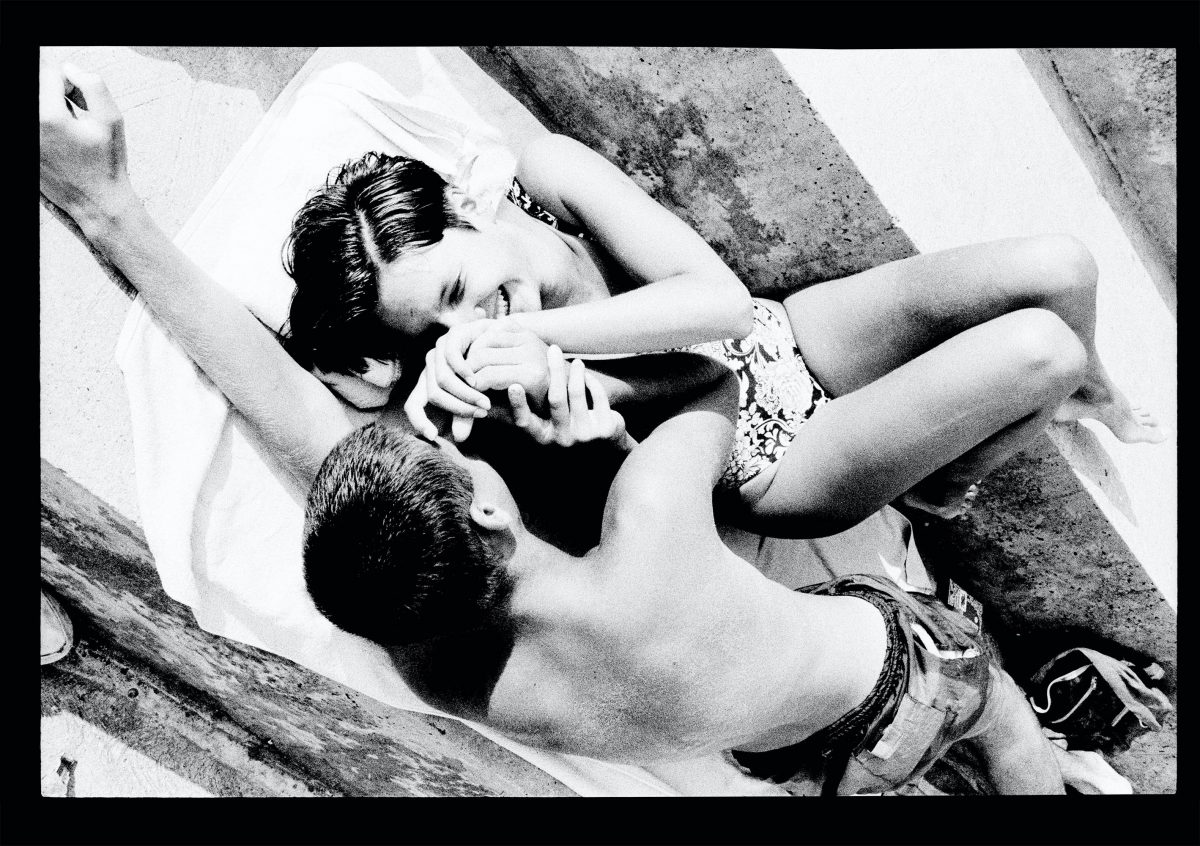

Road to Nowhere also includes poetic portraits, social reportage, and shots of teenagers at concerts or house parties, reminiscent of Graubard’s photos of the counterculture in her native New York City. These pictures give a slight glimpse into the early 1990s in no less than 10 different countries: Bosnia, Serbia, Croatia, Albania, Czech Republic, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Poland and Russia.

“Wanting to learn the stories behind each photo, I felt frustrated by the design decision to drop captions”

Wanting to learn the stories behind each photo, I felt frustrated by the design decision to drop captions, and only provide context for some of the images in disjointed notes at the book’s end. As such, Road to Nowhere

is a mute, meandering, out-of-context representation of Graubard’s journey across Eastern Europe. Flicking through the pages, someone not knowing much about the history of the region might think that all of it was marred by war, gun use and misery interrupted only by rock concerts, house parties and some traditional circle dancing.

As an Eastern European growing up in the 1990s, the book’s title, too, sat uncomfortably with me. Alluding to the tectonic economic and political changes that characterised the countries leaving authoritarianism and socialism behind (with a nod to the Talking Heads hit), it nonetheless feels very much like the product of an American gaze, seeing the states emerging out of the Eastern Bloc as, at worst, non-places, or, at best, an undistinguishable mass.

“Judged as a poetic diary, though, Road to Nowhere online pharmacy purchase strattera online with best prices today in the USA abounds in striking photography”

Judged as a poetic diary, though, Road to Nowhere abounds in striking photography. One evocative image of social contradictions shows two women standing next to each other on a hallway: one pious, wearing a headscarf, the other one pulling off a bright purple-pink lipstick and a fashionable fur coat.

Another portrait sees two kids at a train station, their faces dirty; one of them points a gun to the other’s throat. It’s not a real gun, the notes reveal. These boys live in Bucharest train station tunnels: “The stories of their short lives are all different,” Graubard writes. “They play with toy guns and go into trains looking for leftover food and cigarette stubs. They shower in the public baths and form a family. They get beaten up by police and by each other… They survive until they don’t.”

The kid taking the cow home seems like a sight from my grandmother’s village in Moldova. The Roma children sleeping on heaters in train stations are evocative of Bucharest, where racial inequality is still great, although Roma political and artistic voices have become stronger. The teenagers dressed in black at the vigil of the Russian iconic rock singer Viktor Tsoi in Moscow remind me of a similar gathering my friends and I had to commemorate Kurt Cobain’s suicide. Yet, there are also shots that look like they’re from American films, rather than Eastern European realities.

One such example is an image of fashionable teenage boys by slot machines, one with a cigarette in his mouth, another wearing a T-shirt for Public Enemy’s 1992 album Great Misses. With globalised capitalism and the dominance of American popular culture, all the world now mirrors the US and the West.

“They get beaten up by police and by each other… They survive until they don’t”

We find out that a key character in Graubard’s diary, Cvetko, who worked as her driver and translator in Serbia, is now a long-haul truck driver in Canada, on his third marriage, with six children, including two daughters, one an architect, the other a ballerina. His is a story typical of many Eastern Europeans who fled poverty for better salaries and more stable lives in the West. I admire the fact that Graubard has kept communicating with Cvetko, but without the proper context and notation, I am not even sure whether his face appears in these pages.

Paula Erizanu is a journalist, author, and former culture editor of The Calvert Journal

Road To Nowhere by Robin Graubard is out now (Loose Joints)