The hyphenate persona is not a new concept, but the works of artist-filmmakers Garrett Bradley, Ayo Akingbade and Isabel Sandoval are refreshing in their navigation of the art and film worlds. As interdisciplinary artists in a culture that is increasingly receptive of works that defy easy categorisation, their narratives often explore issues of gentrification, undocumented immigrants and mass incarceration, posing questions that transcend labels.

Garrett Bradley

Bradley continually experiments with form and presentation. The US artist’s short film America was exhibited at MoMA last year as a four-channel, 3D installation accompanied by footage from Lime Kiln Club Field Day, an unreleased film from 1914 (thought to be the oldest surviving feature film with an entirely Black cast). “Moving into three-dimensional space meant that one’s own perspective, one’s own height and curiosity, the way one chooses to move through the work, will present them with an entirely unique perspective of history, of the relationship between one’s past and one’s present self,” she says.

For Bradley, presenting her work in fine-art institutions widens conversations about what it means to be American. It is an ever-evolving theme that many of her works explore, with the hope of “maybe offering new [belief systems] in the process”.

“It requires dialogue, established and agreed-upon intention and most of all, transparency. All of these things add up to respect”

The short film Alone (2017) and the Oscar-nominated feature documentary Time (2020) explore the consequences of incarceration for the families left behind. In these two films, Bradley follows the lives of Aloné Watts and Sibil Fox Richardson (known as Fox Rich) respectively, including their frustrating encounters with bureaucracy while stuck in a limbo experienced by millions of American families. Time uses Fox Rich’s home videos to illustrate the impact of the years spent without her husband Robert. “Speaking from an American perspective, the Black family archive is in many cases the only evidence of ourselves as we see ourselves,” says Bradley. “It is a political act to build one’s own narrative in lieu of the one others will inevitably make for us.”

Effectively the redoubtable Fox Rich becomes an artist too, with Bradley’s film serving as a conduit for her story. Bradley has previously referred to her work as “inherently collaborative”, a mode established by building strong relationships with the subjects of her films: “It requires dialogue, established and agreed-upon intention and most of all, transparency,” she says. “All of these things add up to respect.”

Isabel Sandoval

Filipina filmmaker Isabel Sandoval’s first two features are inherently political. In Senorita (2011), a trans sex worker moves to a small town and becomes involved in local elections, while in Apparition (2012), cloistered Catholic nuns find themselves under siege during the Marcos dictatorship.

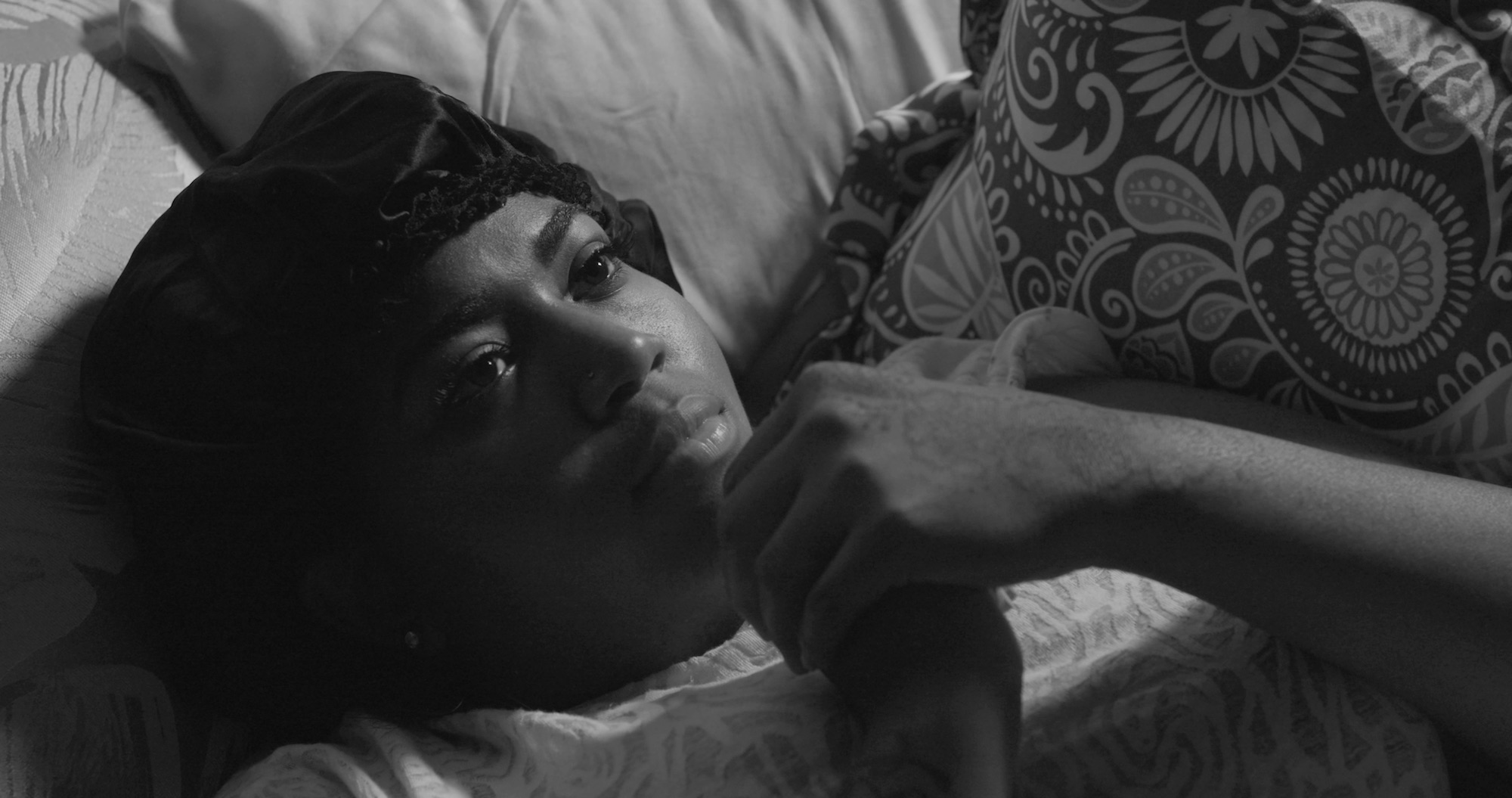

Her most recent feature, Lingua Franca (2019) also explores political themes of immigration and the trans experience in America, but after transitioning and going through “the most honest to goodness journey towards authenticity in my personal life”, Sandoval wanted to reflect that in her work. Determined not to make a film that was “a crash course about what it means to be transgender”, she set out to portray the everyday lives of her characters. “My biggest gamble here is that I demand that a cisgender more general audience, meet me halfway as a storyteller,” she says.

- Isabel Sandoval, Lingua Franca, 2019. Courtesy the artist

“My biggest gamble here is that I demand that a cisgender, more general audience meet me halfway as a storyteller”

Citing the French New Wave and artists like Peter Bogdanovich and Elaine May, Sandoval has “been quite insistent on the term auteur since last year, because given my identity and the circumstances in which I made Lingua Franca during the Trump administration, the auteur has more than just an artistic or aesthetic dimension. It carries with it a political resonance as well.” As a trans woman of colour and an immigrant, it was important for her to demonstrate complete control both in front of and behind the camera.

Sandoval describes Tropical Gothic, her fourth feature, as an inversion of the male gaze of Hitchcock’s Vertigo. It features a priestess who pretends to be possessed by the dead wife of a conquistador, in order to manipulate him into relinquishing her property. It continues Sandovals shift towards a more “lyrical, dreamlike, poetic and sensual” cinema.

Ayo Akingbade

London-born filmmaker Akingbade made her debut short film In Ur Eye in 2015, and has ever since been trying to dodge being boxed into any limiting categories by the business. “They see me as a documentary filmmaker, they see me as someone else,” she says. Akingbade feels that the UK film industry tries to dictate the creative milestones of young filmmakers. “When am I going to stop being emerging?” she asks. “The timeline in this country says you’re ready to make a feature when you’re in your late 30s.” The 26-year-old has other plans.

A is for Artist (2018) wonders who can be an artist and how to tell the world that you are one. Close ups of Akingbade’s eyes as she sifts through old photographs seem to ask how the artist’s gaze renders something such as vernacular photographs. In another scene, Akingbade walks with giant papier-mâché hands, a nod to Sylvia Palacios Whitman’s Green Hands (1977). A is for Artist, turns that ‘A’ into a powerful identifier equal to the first-person pronoun ‘I’.

“The industry will always say you’re not good enough, you’re ugly. They will always try to move people into something that they’re not”

Reflecting on artists who move between the art and film worlds, Akingbade takes inspiration from Steve McQueen, who created works for galleries, won the Turner Prize, an Oscar and received 15 BAFTA nominations for Small Axe, an anthology BBC series based on the lives of London’s Black Caribbean communities. She wants to bring her vision to fruition no matter what form it demands: “I went to film school, and now I’m in the art world. I didn’t ask to be in the art world; they just accepted me.”

She adds, “The beautiful ones always smash the picture,” referencing the track by Prince. “The industry will always say you’re not good enough, you’re ugly. They will always try to move people into something that they’re not. As long as I am confident in what I would like to execute, what I want to do, there’s no one that can stop me.”