Nando Messias, Shoot the Sissy

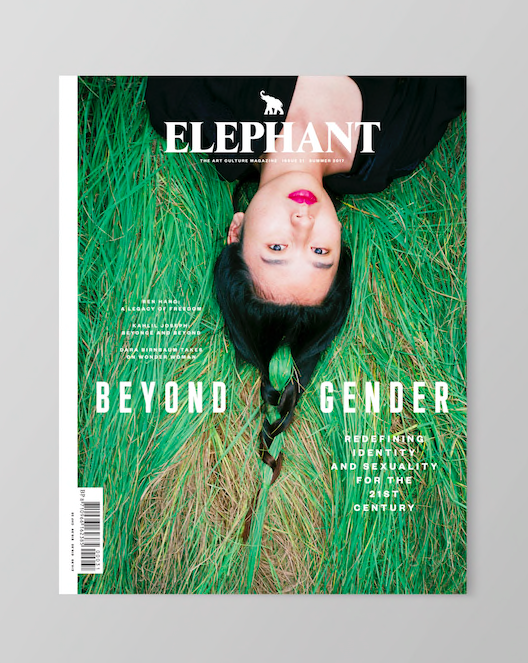

This feature originally appeared in Issue 31.

RuPaul Charles made headlines in September 2016 when he picked up a Primetime Emmy for Outstanding Host for his eponymous reality competition programme, RuPaul’s Drag Race. The show, which Charles also produces, started in 2009 and has now run to nine seasons and multiple spin-off series, such asUntucked, RuPaul’s Drag U and RuPaul’s Drag Race: All Stars.

Produced for Logo TV, the show was aimed initially at the LGBTQ community. But with time, it has bridged the gap with the straight community. Eight years in, Drag Race has grown from being late-night fringe TV into a popular smash hit. Far from simply tolerating the show, mainstream viewers now count among its most dedicated followers. The show’s contestants have also broken boundaries by achieving success outside of queer culture, with chart-topping albums, movie appearances and sponsorship deals.

Perhaps the most significant consequence of Drag Race has been its influence on popular culture. As RuPaul commented when speaking to the Guardian: “It [used to] take about 10 years for something in gay culture to actually migrate to the mainstream. But because of our show, gay pop culture is [now] pop culture in the mainstream.”

That gay culture is becoming indivisible from mainstream culture can rightfully be thought of as a positive effect: Drag Race helps a historically marginalized community become increasingly accepted and understood. The show has had another important cultural effect too. “We’re all born naked and the rest is drag” is one of RuPaul’s pet phrases on the show, and is also the founding idea for the series. Men impersonating women exposes gender for the cultural construct that it is and shows how the art of performance crafts the gendered self into being. To illustrate this, each season features an episode where the queens makeover guest partners into their drag sisters or drag daughters. Across the seasons, their partners, who have been as diverse as US Marines, soon-to-be-grooms and grandfathers, have been fashioned into fabulous queens through the transformative powers of drag. Contestants are scored on how well they are able to create a feminine look on a heterosexual man with traditionally masculine features.

This cultural benefit of RuPaul’s Drag Race chimes with the influential writings of gender theorist Judith Butler. For Butler, it is the acknowledgement and performance of various interpretations of the body that produce the effect of a single gender, rather than the body’s own physical constitution. Gender is the enactment of social norms and the avoidance of opposing taboos. Viewing the workings of gender in this way reveals the problematic ways in which heterosexual norms are imposed on individuals, sometimes to violent, discriminatory ends. For Butler, drag is a powerful tool that can disrupt these damaging assumptions through parody. When drag kings and queens assume an exaggerated character of the opposite sex through the help of costumes and makeup, their audience becomes aware of how they too perform their own genders every day.

Drag’s history has always been tied to entertainment and theatre. Since the time of Shakespeare and the origins of Kabuki, men have often played female roles in world theatre. But since the LGBTQ civil-rights movements of the 1960s, which culminated in the 1969 uprisings at the Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village, drag has been closely linked to political action. While these days he might be better known for his glamazon alter ego, the young RuPaul started out as a counterculture artist on the Atlanta gay bar circuit doing genderfuck drag, an irreverent genre of drag inspired by punk rock.

Arguably, the most visible form of drag is no longer live performance found in underground venues but on Drag Race. The show’s popularity has resulted in its becoming the dominant form of representation for drag culture at large. This has potentially negative consequences for drag, as the show espouses a specific form that can be seen to reinforce a set of gender expectations. Drag Race has embraced queens of different styles of drag, from comedy queens like Bianca Del Rio, to spooky queens like Sharon Needles, to pageant queens like Alyssa Edwards. But regardless of drag style, queens are still expected by RuPaul and the other judges to embody a form of polish and sophistication in their looks and delivery personified by RuPaul. Recently, fans were shocked when hot favourite Adore Delano exited the second series of All Stars after being harshly critiqued by judge Michelle Visage for her look. Delano’s defence was that she had built her brand on her grungy, unfinished aesthetic, but Visage griped about the fact that her dress looked cheap and fitted poorly. A clique formed on season three by queens calling themselves the Heathers popularized the term “booger drag” when they used it to described fellow contestants who were unpolished and lazy in their drag style. One of the Heathers, Manila Luzon, also described booger drag as “crunchy”.

While saying someone does booger drag has become pejorative, a group of contemporary artists today are deliberately embracing crunchy drag as a critical means to interrogate gender performance. In many of his video works, the chameleonic Singaporean artist Ming Wong impersonates the heroes and heroines of the world-cinema canon. Wong’s work is characterized by his trademark brand of hilarity and provocation, born out of a sense of disconnect that arises from what the artist terms “impostoring”. Wong performs roles that often do not correspond to his designation as an Asian man, embracing and exaggerating the misalignments in gender, language and ethnicity.

In Bülent Wongsoy: Biji Diva!, Wong explores the life and career of Bülent Ersoy, the popular Turkish transsexual singer, who embodies the notion of unstable gender identity. Wong draws attention to the performativity of gender as he dons gaudy costumes, portraying Ersoy through the various stages of her life as both a man and a trans woman. The imperfect illusion of femininity created by his over-the-top impersonation further disintegrates to become another layer of illusion—what viewers expect to be Wong’s figuring of femaleness gives way to another grey area when they fail to establish if the body they are encountering is male or female. Through this, Wong’s performance reveals that gender is a simulacrum—a copy without an original.

The Brazilian artist Nando Messias explores ideas of visibility and violence from the standpoint of the effeminate man through his alter ego Sissy. Late one night in 2005, Messias was walking home. Dressed in black, wearing high heels and with his hair up in his signature bun, he was ambushed by a group of young men who pushed him to the ground and shouted abuse at him. They only stopped when neighbours called the police.

Ten years later, Messias returned to the site of the attack for The Sissy’s Progress, clad in a red ballgown, with matching stilettos and lipstick, and a bunch of colourful balloons in one hand. As he walked the streets of East London, a four-piece brass band followed him. After the incident, Messias wanted to explore what it was about himself that had spurred the young men on to attack him. He wanted to efface the effeminate parts of himself to stand out less, and began by removing his makeup and swapping out his high heels. However, eventually he came to the conclusion that the answer was not to dial down this side of himself, but rather to make it “hyper-visible”. The loud music and colourful balloons are an invitation to passers-by to really look and thereby witness the aggression that the queer community experience on a daily basis. Via Sissy, Messias explores the idea of “misalignment”. The term “effeminate” is applied to male behaviour that approximates to the feminine, implying a failure of both masculinity and femininity. However, for Messias, this point of breakdown is both a political site and a productive force: “Effeminacy allows me space to exist in a body that refuses systemic correction.”

Messias reprised the role of Sissy in Shoot the Sissy, this time staging a carnivalesque performance, stepping into the firing line and inviting his audience to throw food and other objects at him.Shoot the Sissy recalls the early works of Marina Abramović, in particular Rhythm 0, where Abramović laid out seventy-two objects on a table and invited her audience to use them to do whatever they wanted to her. With Shoot the Sissy, Messias similarly puts his body in a position of complete vulnerability. The resulting piece powerfully exposes the violence that the effeminate body has traditionally been subjected to as a result of its perceived difference.

Performance artist Dickie Beau works with what he calls “playback performance”, inspired by the drag tradition of lip-synching. Beau’s modus operandi involves a process of “dissecting and re-membering” found audio footage, the latter term meaning literally to put back together and embody. Beau describes himself as a “drag clown”, situating his work at the intersection of female impersonation and clowning—he appears particularly inspired by Pierrot, the sad clown with a melancholic expression in white-face makeup and loose clothing. The character has come to express qualities of solitude, sorrow and sensitivity, while playfully and boldly embodying qualities of gender fluidity.

Blackouts: Twilight of the Idols was inspired by the Judy Garland Speaks tapes. In tapes Garland recorded as notes for a never-written autobiography, “America’s Sweetheart” spoke of her troubled life as she was going through a messy divorce. The tapes grabbed Beau as he identified with Garland’s dysfunction. In the first instalment of the work, Beau lip-synched to Garland’s tapes in a stringy plaited red wig and Pierrot makeup, loosely evoking Judy Garland’s Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz while expressing her desolation in the tapes. He began to search for other iconic women who had the same qualities as Garland, and arrived at the audio recordings from Marilyn Monroe’s final interview with the journalist Richard Meryman, which he obtained from Meryman himself. Wearing a blond Monroe-inspired wig, a cheap nude bodysuit and his trademark makeup, Beau lip-synchs to this footage while also interweaving segments from his own recording of his meeting with Meryman. The resulting work, featuring Beau’s shape-shifting interpretations of both Garland and Monroe, is a haunting study of iconic Hollywood leading ladies in the final stages of decline and exile. The found audio and Beau’s deliberate lip-synching draw attention to the dissonance in his performances of tropic femininity in distress.

Ruby Glaskin, Adam Robertson and Lucy J Skilbeck, who make up Milk Presents, describe themselves as makers of “gender theatre”. Milk Presents’s brand of performance is a form of protest that interrogates the notion of gender as a binary concept. Much of their work features drag kings, who have traditionally received less visibility than drag queens, something that has been much amplified by Drag Race.

Their production JOAN stars drag king LoUis CYfer performing the role of Joan of Arc dragging up as the men she defied in her lifetime. Joan of Arc made history because she was eventually burnt at the stake on the pretext that she had worn men’s clothing. Drag for Milk Presents is a critical tool that is a funny and bold way to unpick the workings of masculinity. While drag does not directly condemn or criticize masculinity, it is nonetheless a hard-hitting way of exposing how binary thinking about gender has historically had damaging, even violent ends.

Extending this, Milk Presents also work with LoUis CYFer to runBuild Your Own Drag King workshops. Amateurs are invited to explore their own masculinity, whether they are men or women, and drag up as their masculine alter egos. Participants hail from different demographics. Drag allows them to explore what it means to perform masculinity and in doing so come to understand how this cultural construct impacts their lives. In one workshop, an elderly lady performed a piece dressed up as a man who got all the opportunities she never had when she was young, set to James Brown’s “This Is a Man’s World”.

With the phenomenal success of Drag Race, detractors worry that drag is losing its critical currency as it increasingly gets swept up into popular culture and reinscribed into mainstream norms and expectations. However, in the work of these artists, drag returns to and refreshes its bold roots in parody, exaggeration and mimicry, inviting audiences to probe our assumptions about gender.

Buy Issue 31