“Oh lucky, lucky you,” my dinner companion said wistfully as I made my excuses, at 11pm to get home to my one-and-a-half-year-old. My interlocutor was out the other end of it—four grown children and a few grandchildren. The words rung in my head as I hurried home. Because truth be told, it’s not often I feel so lucky, though I feel that I should. Tired, edgy, impatient, delirious, bleary, loopy, dirty and happy—those are adjectives I’m abundantly familiar with.

Louis Theroux’s important new documentary on some of the ways birth and early parenthood can affect the mental health of mothers reveals how great the gap between expectations and reality can be. The idea that every woman who is now a mother has grown up fuels the notion that we must be functioning, physically and emotionally. One of the more serious cases in the South London psychiatric unit Theroux visited to film his latest documentary, Mothers on the Edge, is Catherine (pictured above). Catherine had experienced the immense grief of terminating a pregnancy and found it hard to connect with her healthy baby boy Jake, who was born soon after.

Catherine is battling a serious—and well-hidden—mental disorder, that as the programme highlights, is exacerbated by her perfectionism, and our picture perfect culture. Catherine is in profound pain, though you wouldn’t know it—and she is also engaged in perpetuating her own myth of motherhood in which she feels an easy and natural love for her son. The truth is that, as she explains, she has attempted suicide, partly because she has not experienced the “rush of love” she anticipated and felt for the child she lost.

“Tired, edgy, impatient, delirious, bleary, loopy, dirty and happy—those are adjectives I’m abundantly familiar with”

These mothers are at the extreme end of the motherhood experience, struggling with debilitating postnatal conditions that require medical care and support—including postpartum psychosis that can occur out of the blue, with no previous history of mental illness in the patient. It affects 1 in 1000 women who give birth. Dramatically stopping breastfeeding, as is the case of one mother in the film, can be a cause. Despite her high levels of anxiety and exhaustion, however, she is still able to joke with her son about the size of his “bad boy” poo. It is remarkable to glimpse these moments.

While these cases are extreme, any parent, and especially, every mother, can identify with what the psychiatrist on the mother and baby unit describes as “perfect storm” of hormones, sleep deprivation, the responsibility and life changes that a new mother goes through—overwhelming is a word that keeps coming up. In my own experience, I’ve felt my mental health teetering on the edge at times, especially after prolonged periods of sleep deprivation that feel endless, and round-the-clock care compounded by the regular stress that life brings. There are other times I have felt I’m totally disconnected from “reality”, with Frère Jacques stuck on repeat in my head (much like the demented nanny in Curb Your Enthusiasm who constantly hums the theme song from Looney Toons).

“Tanning was never a mother—nonetheless, she understood entirely what it meant to be a woman, and broken, in different ways”

Frankly, without the support I have had, I would not have coped. Another of the mothers in the film explains that for her, the warning sign was the point that it all felt only like “hard work”. When other people seem to enjoy every moment they’re with their children and you feel this way, putting on a brave face is often not a choice.

Louis Theroux: Mothers on the Edge © BBC. Photographer: Richard Ansett

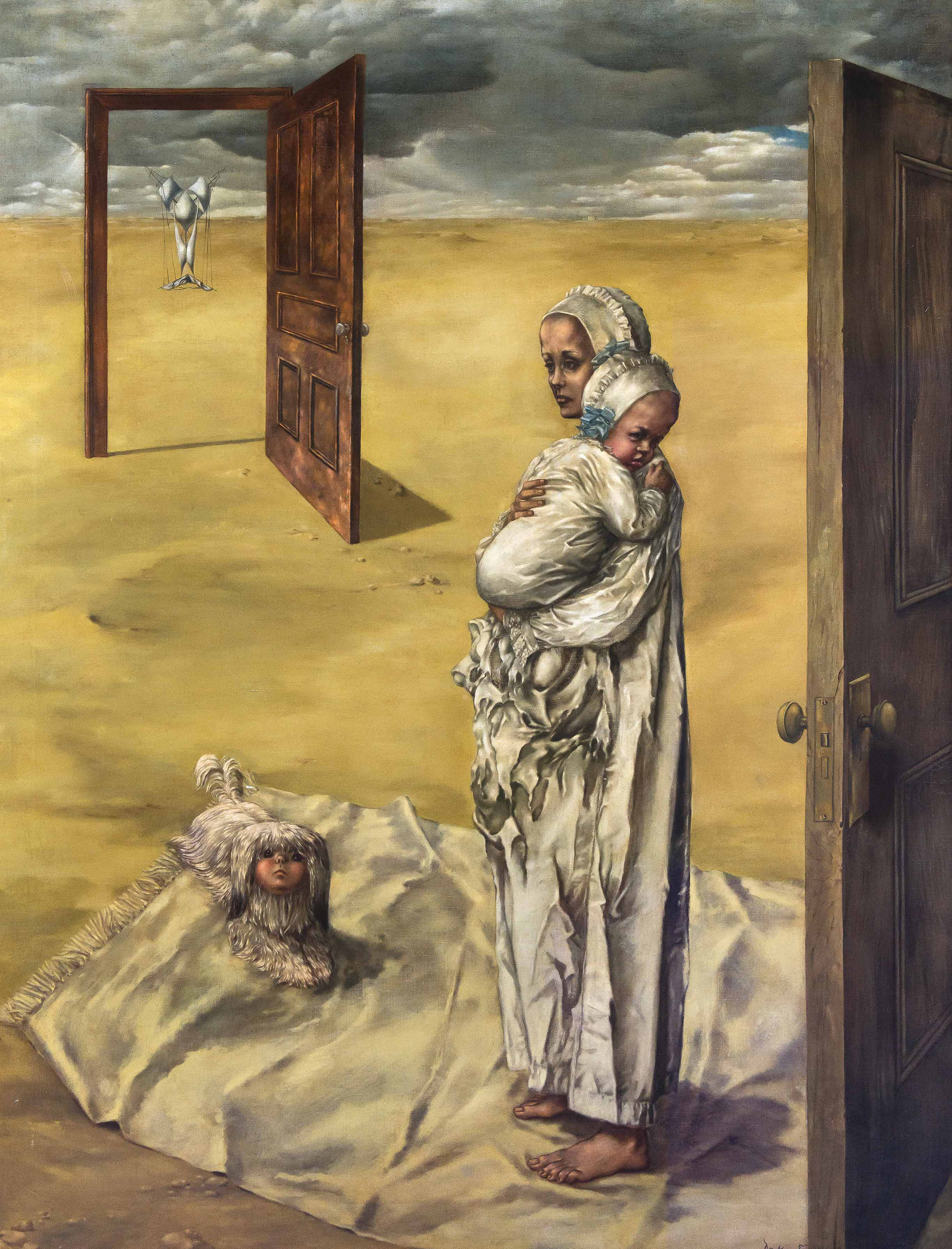

At Dorothea Tanning’s exhibition at Tate Modern, it comes as a great relief to see motherhood depicted in nightmarish glory. The American painter who passed away in 2012, aged 101, paved the way for lifting the lid on the disturbing and sinister side of a women’s psyche. Her dimly lit surreal haunting masterpiece of 1947, Maternity, spotlights the mental and emotional state of a new mother; a grim look on her face, barefoot and in a tattered white dress, gripping onto her child, standing alone. There is great emptiness and at the same time, vast love, in the painting. Tanning was never a mother—nonetheless, she understood entirely what it meant to be a woman, and broken, in different ways. Seeing this kind of depiction hanging in a major museum is vital; it gives the negative experiences equal validation and space as the glossier positive portrayals we are used to, the latter often more harmful for those who are having a rough go of it.

Taking one day at a time is one method—and a network of support, that can come in any shape or form, is also clearly a lifeline. What that conversation at dinner reminded me of was how little time you get to pause, to breathe in the moment and take stock—even if you might find yourself scattered. As Tanning put it: “Keep away from ads, idiots and movie stars.” In other words, don’t let the images and expectations machinate against you.