Arising from the heart of punk culture in 1970s Manchester, Linder Sterling is renowned for her anarchic approach to challenging conversations surrounding gender, sexuality and societal norms. As a visual artist and musician, her work spans collage, performance, fashion design, sound and infamously subversive photomontages, splicing imagery sourced from Playboy magazine, the Surrealist and Dadaist movements, pornography, pop and consumer culture advertisements. Her influence on subcultural history is unmistakable and her work continues to challenge conventional perceptions and dialogues on current-day issues. With a career spanning several decades, our conversation covers what punk means today, creating deep fakes online, glamour, and the profound impact of her feminist perspective on the ever-evolving landscape of art. When Sofia Hallström met Linder Sterling outside of the Hayward Gallery, Sterling was clothed in Ashish, her waist-length hair elegantly tied back, clutching a pair of scissors – a homage to her cut-and-paste collage technique.

Sofia Hallström: We can’t wait for your upcoming exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in February 2025. Could you tell us what we can expect from the exhibition?

Linder Sterling: I’m lucky to have had retrospectives in the past but this will be my first in London! At the moment, I’m at the stage of wondering what’s different from previous shows at Kettle’s Yard (2020), and even going right back to the respective show in Paris (2015). This is very exciting as it’s at the Hayward, an extraordinary brutalist building, which feels like the perfect place to present my work. The show will span 50 years of work, literally half a century of work, which makes me gasp! A lifetime of photomontage, drawing, performances, working with fashion designers, and obsessions with perfumes.

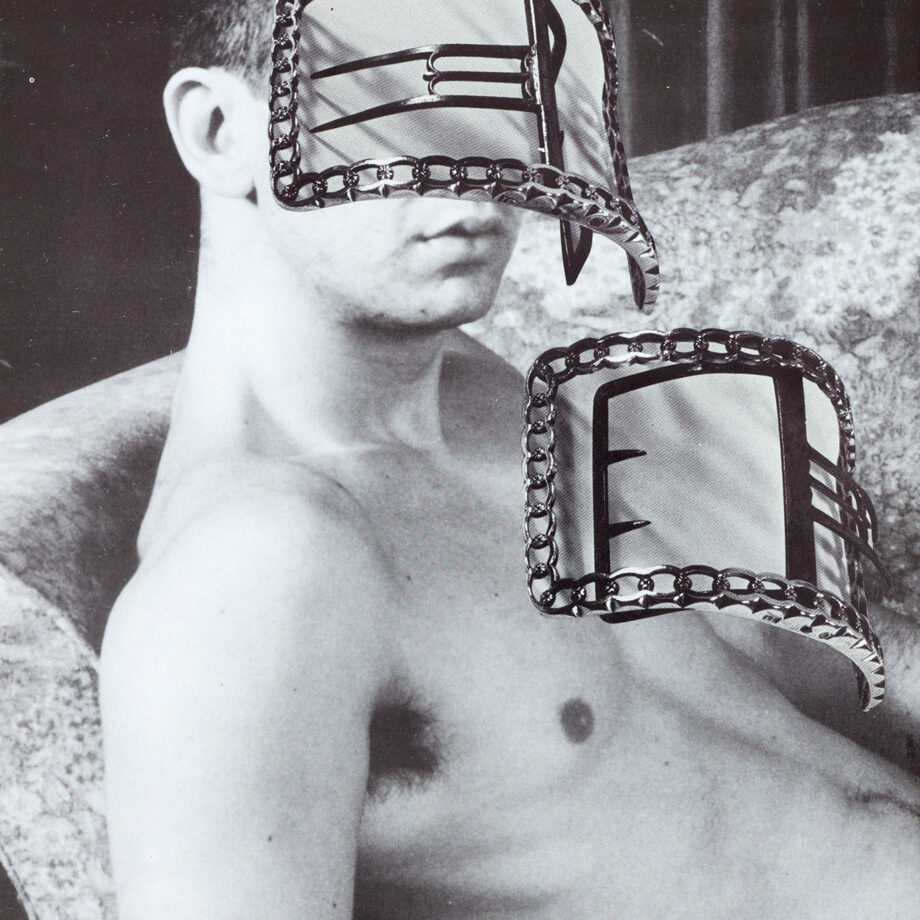

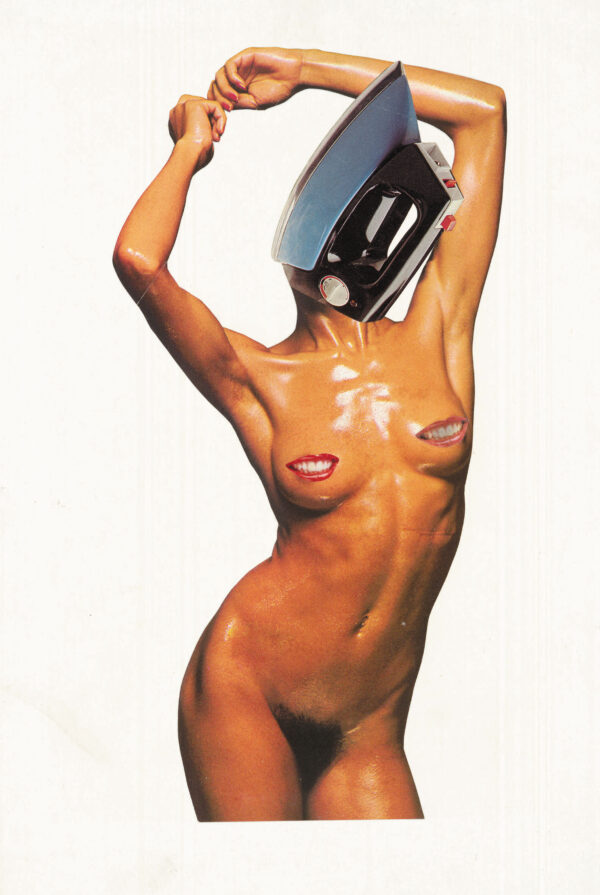

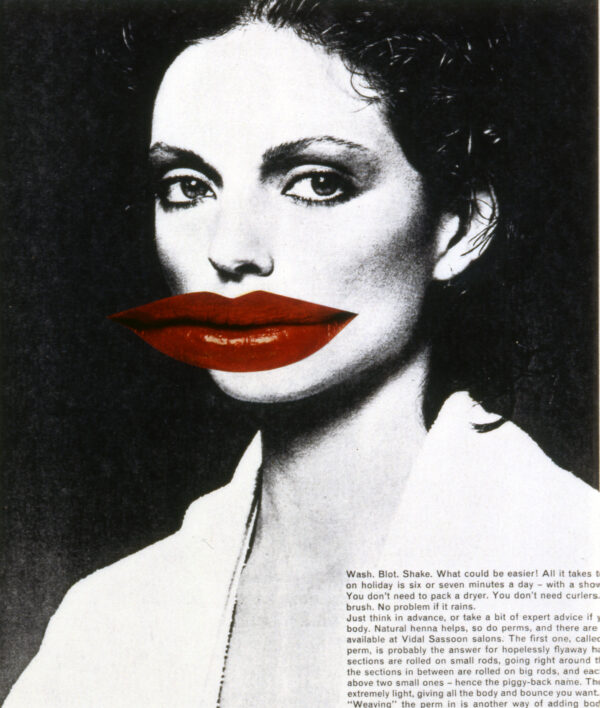

At the moment, I’m looking at pornography once more. I’ve been working with pornography since 1976, and a lot of those early images we see very differently today – for instance, on a very simplistic level, that women didn’t shave their pubic hair then and the furniture is different in the background. Now, we have deep fakes happening. A woman’s life can be destroyed overnight, and it’s so easy to make these deep fakes. I look at my work, and you could say that I’ve been guilty of making deep fakes for decades now as I replace women’s heads with blossoms or domestic utensils! For the show, I may deep fake myself. I’m excited by this idea, I want to have fun with it and make everything slightly skewed and off kilter.. There’s conversations with AI too, which I’m interested in using in my work. What do you think about AI?

SH: I think it could be useful, it has the potential to offer new possibilities for innovation but also raises important questions about creativity and ethics… It’ll be interesting to see how it will develop in the future.

LS: I think with any new technology, for instance, when the printing press was invented, people get really upset about it. We’ll have this period of concern and fascination that will eventually settle. For me, it’s how to make work in response to new technology. I’ve mainly worked with paper for so long. In 2012, I was working on a show in Paris, and I went to the Quartier Pigalle to buy some magazines to work with. But almost all of the magazines were gone, there were only DVDs left. Apart from some bestiality magazines which hadn’t sold, which I did end up working with and producing a series from, I was determined to find the poetics in those forlorn photos. Pornography is all about profit, so why print it in magazines?

SH: There are conversations now about print being so expensive and difficult to fund, but it’s so important to have something that’s tangible…

LS: We are basically mammals who like to rub up against things, to hold things and to have that kind of aesthetic experience with a book or magazine. I do get tired of seeing everything through a screen, I have a longing for paper, for ink, for a sense of weight. I might work with AI for sound pieces. Ralph Rugoff (Director of the Hayward) suggested that I should put all the music tracks I’ve recorded through AI and I will get a thousand remixes… which I might try for the show!

SH: Feminism is a recurring theme in your art. How do you observe the development of feminist discussions within the art realm since your work first emerged, and what do you envision for its future trajectory?

LS: Feminism never goes away. Take for example the YBA era, where culture in general was very laddy, it felt to many as if gender politics was almost done. There are periods within the art world where feminist discourse becomes very faint, and the mark left by that ideology is faint. There is some very healthy criticism surrounding feminism and rethinking how all encompassing the past has been and question, is the work we are doing working on behalf of all women, or just one aspect of society? But for me, it’s like my oxygen. When I was 16, the first feminist book I ever read was Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch. The early feminist writers were so thrilling to me, they used language in such a magical way. If you look at the etymological root of the word grammar, its root is linked to glamour. I was in a small village in the north of England. I remember reading that book with a dictionary next to me, and looking up words like ‘clitoris’. I could feel the synapses in my brain firing up in a very different, magical way. I didn’t fully understand all the language, but I remember it was making me think in very different ways and question everything. When I work now, I still want to tap into that excitement. When I think of feminism, and its journey throughout my lifetime and work, it pulses away in the DNA.

SH: Your early work, particularly your collages, challenged traditional notions of femininity and sexuality. How did your upbringing and surroundings influence these explorations?

LS: I mean, it’s still hard to explain, but essentially, I changed my name to Linder, inspired by German artist John Heartfield angelising his name as a protest against Nazi Germany. This led me to adopt the German spelling of my name as a protest against Thatcherism and I sliced off my surname. It was an attempt to challenge norms, especially in a male-dominated art scene where my work was often assumed to be made by a man. There were men whose jaws dropped when they realised that I, a woman, had made the work! The experience of buying pornography magazines in a male-dominated environment was shocking yet empowering, eventually influencing my art through simple yet impactful photomontage techniques. I was also looking at Vogue and other magazines for images of housewives and fashion models, photographs of cakes or knitting patterns. In those early photomontages, I put these two worlds together, it was so simple!

SH: A lot of different worlds collide in your work, particularly with music. I wanted to ask you about the collaboration with the Buzzcocks, designing their iconic Orgasm Addict single cover, which became a seminal piece of punk art. How did your relationship with the punk scene inform your artistic identity and approach?

LS: I find it almost impossible to talk about punk now, as there are too many preconceived ideas about it. There are adverts of a new mascara that is advertised as punk, so I struggle to discuss punk without encountering clichés. It’s almost bankrupt now. When I embraced punk in 1976, I went back to Manchester Polytechnic in September, and I had managed to save up enough money to buy a pair of the bondage trousers designed by McLaren and Westwood. I was wearing them with a PVC top. I will never forget how I was met with silent shock on the streets. People were just stopping and were silent. In those first few months of punk, there was a degree of heroism to being a punk. All of us were attacked and subjected to physical violence, I had my front tooth knocked out. The initial extreme reaction eventually faded into mainstream acceptance over about four months, and I remember thinking “Punk is over!” Also, you have to remember the context that punk was born from, there was poverty and times were very difficult. It’s not just about having spiky hair! For the first time now, it feels like there could be a revival of something that really questions everything and there could be a radical reinvention in today’s context.

SH: Your work often challenges societal norms and expectations, particularly regarding gender roles and consumer culture. What role do you believe art plays in provoking social change, and how do you navigate the balance between aesthetic expression and activism?

LS: Sometimes, I think that fashion can be more impactful compared to art. Huge swathes of the population don’t go to art galleries. As an artist, it’s crucial to reach beyond the confines of traditional art spaces to engage a wider audience, which is why I work with popular culture so much, to truly impact society and influence change, especially considering the limitations of gallery settings in reaching certain demographics and influencing policymakers.

SH: Collaboration has always been an integral part of your practice, whether you’re working with musicians or fashion designers outside of the gallery space. How do these collaborators influence your process? What do you believe is the value of interdisciplinary collaboration within the arts?

LS: Collaboration is very important to me. I delve into old books and magazines, engaging in periods of photomontage, exploring the nuances of images and gestures. Each still image becomes a canvas for potential movement, inviting curiosity about the reality behind the captured moment. When I work, there’s a dance between vision and embodiment, amplifying gestures and expressions to provoke excitement. Collaboration enhances this process, facilitating an exchange of ideas that fuels rapid growth. Whether it’s a fashion designer suggesting a new cut or a musician proposing a chord sequence, each contribution inspires others, creating a rich tapestry of creativity. Performance, for me, is the perfect antidote to solitary studio work, offering a visceral and socially engaging experience. It’s about creating imaginary worlds and inviting others to join in, transcending barriers through music and gesture. Performance becomes a space for liberation, where spectators become participants, breaking free from the confines of traditional art consumption. I once orchestrated a 13-hour performance, and audience members were prefaced that they could stay for as long as they wanted to, but some audience members told me that they had stayed for eight hours and hadn’t realised that this amount of time had passed!

Women in the 1960s described themselves as the Women’s Liberation Movement, and I think that feminism has a movement in it. I think performance is like People’s Liberation: you’re inviting people in and inviting spectators to move so that’s an important thing as we all sit looking at laptops all day. Openness to participation is key, as we navigate the fluidity of creativity together. Brian Eno has a good definition about Pop music: “Pop music is all about creating imaginary worlds, and inviting others in to join you.”

SH: Your imagery often features juxtapositions of seemingly disparate elements. Can you elaborate on the symbolic significance behind some of these juxtapositions and how they contribute to the narrative of your work?

LS: I remember going into my second year at Manchester Polytechnic in 1976. I had this delight of cutting magazines up, and seeing what happens if I put a cake with icing and sugar next to a woman pictured naked on the bed. I got this visceral pleasure from doing this. Sometimes it’s quite minimal. I wasn’t thinking intellectually when making, only through a sense of playfulness. The Dadaist photomontages referred to themselves as engineers, but for me it’s much lighter than that at times, rather my touch feels radical in that it can be quite fay, camp and light.

SH: How do you manage the delicate balance between personal expression and public interpretation when portraying the human form, especially considering societal norms and pressures?

Linder Sterling: In the area of taboo, in the 1970s and 1980s, everything was taboo! Taboo fascinates me, I want to understand the mechanics of something that we aren’t supposed to be looking at. If I know how the erotic charge is being generated, I can then short-circuit it. I get hypnotised by something that is taboo, almost like I have to work it out. Today, I don’t know what the taboo is… life was so much simpler when everything wasn’t online. Pornography and taboo has become aerosolic, I think it’s at its most dangerous. Anyone can do anything online, and you can’t really track this. I worked with Mia Khalifa for Crash Magazine, she’s now a spokeswoman for women working in the pornography industry. We did a shoot the day after she did a talk at the Oxford University Union, which is really worth watching on YouTube. Nobody can argue with her, she has been slut-shamed on an industrial scale. We met at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Paddington, as of course Mary Magdalene was also shamed for her intimate relationship with the saviour and was criticised for being evil as she was blonde. We did this photoshoot for the magazine there and I put Mia in a blonde wig to reference the saint’s long blonde tresses. I have such deep respect for her. Hopefully we can do something together for the Hayward show.

SH: Online harassment and abuse have emerged as serious threats to women’s participation in political discourse and activism. What steps do you believe are necessary to combat online gender-based violence and create safer digital spaces for women to engage in political dialogue?

LS: I’ve been thinking about this a lot over the last year or two, especially when thinking about creating deep fakes. Even just the action of thinking about making a graphic visual response feels like taking control of my own image before anyone else can interfere with it. I have a one year old grandson, and I think about the pressures on both boys and girls now. We think that girls have it tough, but boys too are under pressure to behave in very gendered ways with toxic influencers such as Andrew Tate in such powerful positions. In the present moment, we can’t take true care online so we have to keep up to speed with the ever shifting undercurrents of risk until much needed changes in legislation protect us.

Written by Sofia Hallström