She could be your ideal woman. This Japanese sex doll, manufactured in China, is certainly the same size and shape as your average twenty-something female. And her silicone skin feels about as close to human flesh as you can get.

For the last few years artists Laurie Simmons

have been using life-size dolls to analyse the problematic representation of women in Western culture. Throughout the history of art women’s bodies have been objectified, and since the advertising boom of the 1950s, women’s bodies have been objectified in popular culture more than ever before, with integrated media channels preaching a message of female perfection. The commodification of women’s bodies, it seems, is only growing in topicality and importance.

- Laurie Simmons, (left) The Love Doll/Day 30/Day 2 (Meeting), 2011; (right) The Love Doll/Day 12 (Bathtub), 2010

Simmons enjoys the sensual beauty of the life-sized Japanese dolls she works with. After first discovering the plastic sex props in a Tokyo shop, she ordered two online and has since used them in an exploration of one of her key themes—the woman in interior. The Manhattan artist has an impressively in-depth knowledge of the intricacies of the sex-doll industry. In 2010 Simmons began creating scenarios with the dolls in which they are all indoors—Love Dolls sees the lifelike figures relaxing in the bath, observing a mouse on a piece of cheese, getting married. The styling of the dolls is intentionally glossy—perfect hair, made-up faces, a good book, cool clothes. Simmons ignores the fact the dolls are designed to function as sex objects: “Somewhere in my fantasy life was this idea of working with a life-size doll. Suddenly finding a character that could move around the scale that I needed was exciting. I picked a doll that was closest to a hybrid anime fantasy. The fact it was a doll used for sex seemed secondary.” Simmons credits Vermeer as an inspiration: “I’m aiming for the stillness of a Renaissance or Dutch painting. Ultimately I want a beautiful picture and a lovely end result. I’m not dramatic, I just want to stop and get people to see a theme.”

In Bride a doll looks wistfully out of the window surrounded by layer upon layer of a wedding dress. “Bride happened because I had a friend who was getting married and she was exactly the same size as the doll. I asked if I could use her dress. I guess I’m presenting, like in a painting, my view of the wedding for women. It made me think of the fantasy of the wedding and how doll-like the woman becomes.” In 20 Pounds of Jewellery, the photograph which gained Simmons a Prix Pictet Award nomination, a naked doll sits perched on the edge of a sofa covered in cheap costume jewellery. On the surface she’s a consumerist vision of wonder—young, glossy, holding jewels—but, sitting naked, she’s also vulnerable.

In Simmons’s Kigurumi project she works with cosplay, the Japanese trend of wearing costumes in public. On her Instagram page Simmons recently posted a self-portrait wearing Kigurumi-style costume. “[Cosplay] isn’t for me, though,” she says. “I feel claustrophobic and it’s important that when I shoot people in the outfits that they feel good.” Clothing models and friends in full body outfits, the Kigurumi series looks at privacy and masking at a time when social media has made over-sharing a buzzword. In contrast to the photogenic confidence of Love Dolls, the Kigurumi dollers gaze out into the world with huge innocent eyes, self-consciously pose in pvc, neurotically clutch a plate of cakes and dramatically hold their heads. Simmons is interested in the women who recently made the news for turning themselves into life-sized Barbie dolls, and explores the insecurities behind such actions through these hyper-glamorized masks. She insists that everyone in the masks loves wearing them, however: “The people that wear the costumes are all ravers, clubbers, people who really enjoy dressing up.”

“The Manhattan artist has an impressively in-depth knowledge of the intricacies of the sex-doll industry”

“I think the media has a lot of responsibility in the construction of roles and behaviour for women,” says Domínguez. “The images we see on tv or in magazines act as references for us and involve messaging that is pure fiction.” Domínguez’s Fashion Victims, which used both real women and dolls, was staged on a hot afternoon in Madrid and saw effigies of fashion bloggers buried under rubble—a comment on the horrific conditions for women in the workshops of Bangladesh, referencing the deaths there when the Rana Plaza factory collapsed in 2013. “Bloggers and celebrities are brand representatives for women and are also aggressively torn down. Women are either perfect, or so far away from perfect that they should be laughed at.”

Domínguez is forthright in her criticism of the fashion media, and she openly digs away at the relationship between the fashion industry and working women across the economic spectrum. “I think it is unfair to use the term ‘fashion victim’ to name someone who decides freely to buy clothes,” she says. “The real fashion victims are those who suffer the negative aspects of the fashion industry without meaning to.”

It’s not only female artists who are using dolls and robots to explore such issues. Jordan Wolfson’s Female Figure aims to capture the physicality of female bodies. Attracted to the design principles behind animatronics owing to the specific movement you can achieve with a robot, the piece was made at Hollywood special effects studio Spectral Motion. Wolfson was aware of the problems he might face. “I knew it would be difficult to represent women as I’m male, maybe even impossible except from a male perspective, which I feel is problematically interesting.” Clad in dirty white clothes and matching boots and with a shock of blond hair, the robot dances to remixed music like Blurred Lines, a controversial pop song about male and female relationships. It’s a puzzling representation, not least because of its witch mask. “I’m interested in a kind of primal sexuality that I experienced while looking at representations of the female figure,” says Wolfson. “I wanted to bring that into my work but at the same time negate it with opposites, hence the device of the mask which represents the opposite of fertility as it’s a witch.”

Another male artist is offering an interesting commentary on our media-saturated world and the female body’s place within it. Pandemonia—a six-foot-two pvc-clad character created by an anonymous male artist; this is a doll that’s actually worn by its human animator—looks at the latter as the most effective advertising device known to contemporary culture. By taking ownership of the hyper-glamorized image of women in the media through an object, the work criticizes a society that commodifies women.

- Ditzy Blonde Photograph of Pandemonia, 2013

- Female Figure Jordan Wolfson, 2014

“Pandemonia is an allegory. I wanted to make some work that was relevant about today. She’s a critique of the media, carried by the media. Painting and sculpture were ill-equipped to investigate such topics. I constructed a celebrity so my image and ideas would be carried by social media and the press.” Through Pandemonia, the media’s expectations of women are ridiculed with a manufactured send-up of a modern female. It’s a ruse often lost on the fashion industry, which Pandemonia dips in and out of. The doll is invited to fashion shows as a front-row guest, photographed next to celebrities, editors and models.

A caricature of the media circuit loved by the very same network of people she criticizes. This is how the dolls become art.

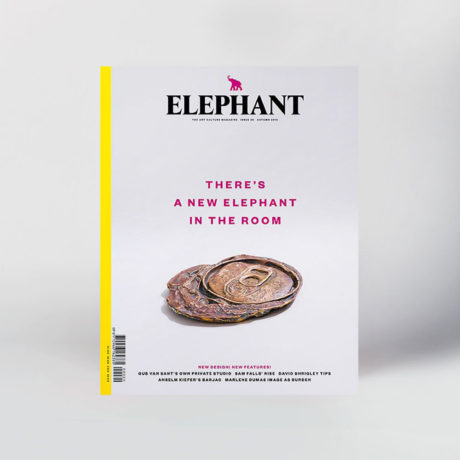

This feature originally appeared in issue 20

BUY ISSUE 20