Joseph Albert Alberdingk Thijm, a seventeenth-century Dutch art theorist, believed that there was a lost symbolism of gender hidden in gothic design. To Thijm, the twin towers prominent on many French cathedrals embodied male and female qualities—the male tower larger, decorated with symbols of power, the female tower smaller and more delicately ornamented.

One advocate of Thijm’s theories was the young architect Pierre Cuypers, who incorporated the gendered symbolism into the two towers of St Catherine’s, a monumental neo-gothic church in the heart of Eindhoven. Completed in 1867, the building’s grand architectural features—its vaulted ceiling, soaring arches and ornamented towers—emulate the forms of stonemasonry with the materials and techniques of brickwork.

Some 150 years later, a short walk west of St Catherine’s, another theorist has turned their attention towards the role of gender in design. Viola van Alphen, curator of Manifestations

, has brought together a group of young artists whose work embraces new materials and techniques to reimagine old ways of working.

Now in its third year, Manifestations has transformed the ninth floor of a former storage warehouse into an anarchic space. Intermittently, the room is filled with the deafening roar of twenty-five angle grinders—a spark-producing array that forms one of the exhibition’s most spectacular exhibits. Van Alphen threads her way between pillars astride a bicycle, her pink Adidas jacket a stark contrast to the concrete backdrop.

As a lecturer at the University of Twente, Van Alphen found there was a gender divide in her students’ relationships with technology. “My female students were not comfortable with the way that the male students were dealing with technology. They wanted it to be nicer and more caring.”

Van Alphen believes contemporary design is dominated by “male techs and managers looking for profits”, resulting in a material culture of uniformity, unyielding materials and suffocating control. The artists featured in Manifestations—the majority of whom are women—reflect Van Alphen’s vision of a more conscientious approach to making, renouncing the cold homogeneity of mass-produced glass and metal in favour of organic approaches and softer materials.

That approach to materiality is evident in the work of Tessa Petrusa. Heading into the exhibition space, visitors encounter arcing forms of fabric, ribs rippling beneath their translucent skins like deep-sea creatures. Petrusa acknowledges the natural influence: “That’s where I get a lot of inspiration from—even the lines on these forms are based on the stripes that fish have on their bodies. I use them now as ribs to give strength to the whole piece.”

Petrusa works with off-the-shelf 3D printers and stretched fabrics to create works using a process she describes as 4D printing. “I call it that because you print it with a 3D printer, but a fourth dimension—time—is needed to get it into its final shape. It needs a little time to form. It’s not something I do on the spot. It’s something that I try to pre-programme.”

Rather than creating her pieces through traditional pattern cutting, Petrusa prints rubber directly on sheets of knitted fabric. The tension causes the sheets to fold themselves into three-dimensional forms, with the resulting shapes dictated by the interplay between the materials. “When I print it the material is completely flat, and then it just folds itself. What I’m trying to do is really get a feeling for which patterns will form into which shapes.”

“It has strength but it’s still soft, and to me it looks inviting—it looks like something you want to touch.” Petrusa believes that, in time, the technique can be scaled up to create larger, multi-part objects: “The idea is that these are all pattern elements and that will finally connect so that you can build up large organisms.”

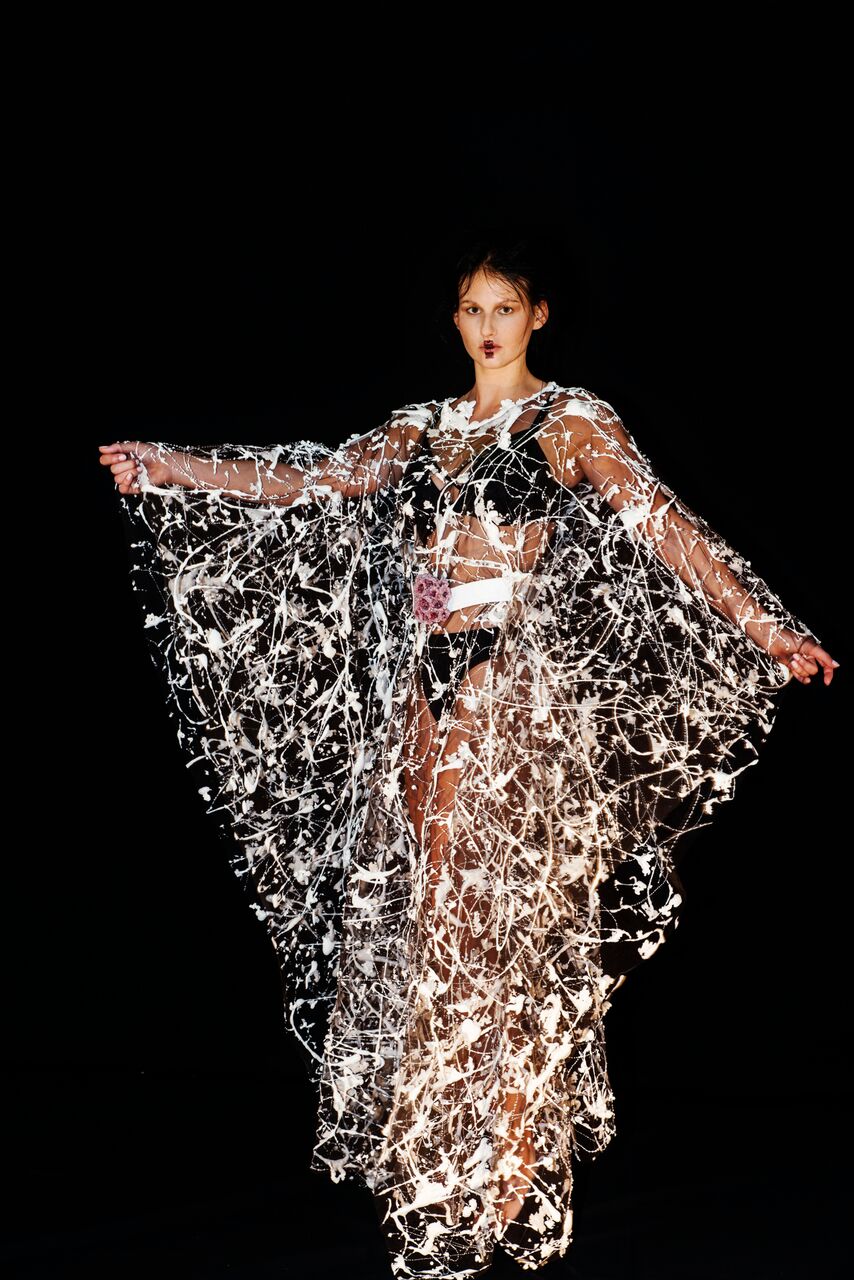

Organic influences are also central to the work of Tim Dekkers, an artist who works with grown materials to create pieces that he describes as sculptural fashion. “I start all my projects with material experiments,” says Dekkers. “Materials have to tell a lot about my concepts.” Dekkers’s display is flanked by two storage units, the shelves lined with red cups. Each cup yields a uniquely shaped tuberous white growth, their sizes varying wildly from a few centimeters to several inches.

“It’s polyurethane, a plastic,” Dekkers explains. “I use the wrong mixture in its liquid state and, because the mixture is wrong, it grows out of itself, this shape. So, it’s a manmade material but it has a natural shape. It’s the same mixture every time, but somehow it reacts differently—it’s very organic.”

That raw material forms the basis of his sculptural works, from stilettos to full-body pieces. “After a week I take those pieces off that are grown and make my objects with them—my shoes and outfits are all made out of those small pieces that are grown out of the cups.”

For Dekkers, the organic element of his work is a statement about humanity’s relationship with the natural world. “I compare humanity with a parasitic fungus. The fungus grows on trees—it kills the trees but also kills itself. I see similarities with humanity. We need the earth to live on, but we also destroy her, we are overgrowing her.”

“The materials look beautiful but the model who wears it has to suffer”

Alongside the polyurethane pieces are jackets and shoes built up from scarlet florets of felt, the softness of the fabric offset by crystal structures bonded to the material, brilliant white and hard-edged. “The materials look beautiful but the model who wears it has to suffer—the crystals are heavy, they are hard, you can cut yourself on them. I wanted to show the beauty of the people killing the Earth.”

Near Dekkers’s display, a circle of glass display cabinets houses a collection of objects that seem to straddle the natural and the artificial—circuit boards embedded in living tissue, tufts of hair growing from skin-clad electronics. These are the work of Nicole Spit, an artist who draws on her background in industrial design to create speculative pieces exploring the impact of biotechnology.

Spit was influenced by recent breakthroughs in gene editing techniques, from eliminating malaria-carrying mosquitos to altering the patterns on moths’ wings. “I did a lot of research into trends in biotechnology, and that’s where I started to spark—Oh wow, is this reality now, already?”

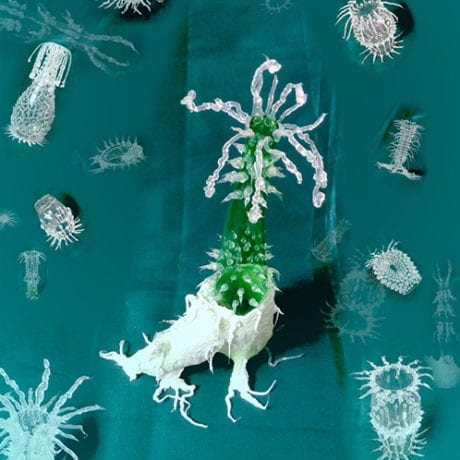

In Spit’s view, the emergence of biotech heralds a shift not only in our relationship with technology, and also in the forms that objects will take—something she explores through a series of vases inspired by microbiological structures. “When these products are on the market, then other companies will also begin to incorporate the design language of biotech—membranes, soft textures, growing forms.”

Faced with these innovations, does Van Alphen feel anything has been lost in leaving behind traditional techniques? “That’s my only criticism of young kids these days—they’re all reinventing the wheel themselves without looking at the past. There are old craftmanship skills and we should not lose them.

Bruce Sterling, a science fiction writer who helps us with the topics here, said that the past is a kind of future that has already happened. I think we can achieve our goals a little bit faster and more healthily if we learn from the past.”

With Manifestations, Van Alphen hopes to nurture a culture of activism in shaping our relationship with material culture. “Artists have this responsibility—to make us more active in this world and to think about how we want this world to be. And that includes the role of the objects that impact us.”