In Périphérique, we follow French-Algerian photographer Mohamed Bourouissa through the claustrophobic geography of the Paris-area banlieues. In decaying structures, abandoned and marginalised places, he introduces us to young people, mostly non-white, longing for a dignity so often denied to them.

The book’s title carries a double entendre: it refers to the name of the Paris ring road (boulevard périphérique) which separates its Hausmannian city centre from its suburbs, but also suggests a fringe, an excrescence, a periphery. In the 19th century, these spaces were elusively called la zone, delineating a “here” and a desolate “there”. Post-WWII, la zone was integrated into the technocratic language of public administration and management in manifold acronyms such as ZUS (Zone Urbaine Sensible, which translates to Sensitive Urban Zone

).

Born in Algeria, Bourouissa moved to a Paris banlieue in the early 1980s. As such, his gaze is one of an insider and the photographs question externally-imposed points of view and urban myths. I similarly grew up in a “there”, in a banlieue where many children of my age, whose parents came from other shores, had names that carried the echoes of Mediterranean and African sunshine.

“Bourouissa’s gaze is one of an insider and the photographs question externally-imposed points of view and urban myths”

The book contains two bilingual essays. In the first, Taous R Dahmani recalls the “partial stability between those who inhabit and those who gaze. She summarises Bourouissa’s intention, which is “to deconstruct the stories told from above and from afar.” In the second essay Clément Chéroux

discusses the historical and sociological connections of Bourouissa’s work.

Bourouissa’s photographs act as an archive of recent memory (2005-2009). In 2005, two young men were electrocuted as they ran away from a police inspection, triggering clashes which spread across multiple banlieues. Bourouissa, then in Algeria, watched this unfolding on TV. I remember sitting in my home in a nearby banlieue following the news with a contagious and unabated sense of rage against the continued othering of my fellow residents.

Bourouissa’s photographic work La république conveys all the drama of a Renaissance masterpiece. Dated Christmas Day 2005, the image introduces a symbolic and physical scene of contestation. In the middle of what resembles a protest, young men of colour wave the French flag to a crowd, and a policeman looks at them as if about to intervene. Le Reflet (2009) shows a young man in a hooded sweater. He rounds his back to the camera, adopting a defeated posture in front of a wall of TV screens.

“The apparent uniformity of decrepit high towers and fashion codes intersects with intimate and personal narratives”

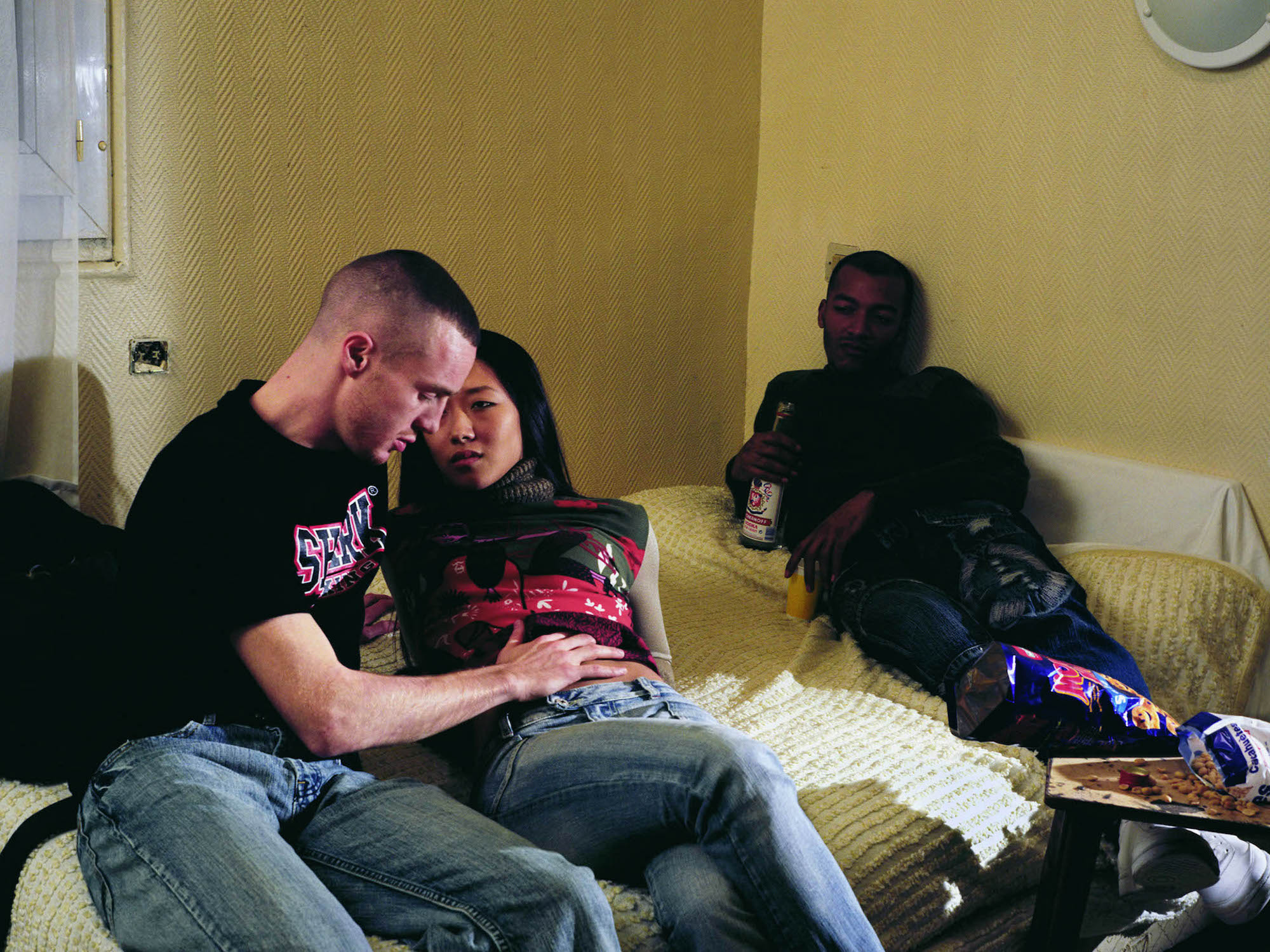

Bourouissa uses split photographs and foldable pages to highlight multidimensionality, to visualise group and individual scenes, to present a landscape as well as sub-chapters or micro-scenes. Building on earlier projects such as Nous sommes halles (2003-05) in collaboration with Anoushkashoot, he offers insights into the lives of people that traditional media present merely in unruly terms, in moments of collective rupture and mass dissidence. The apparent uniformity of decrepit high towers and fashion codes intersects with intimate and personal narratives.

Throughout Périphérique, young people try to reclaim geographies as best they can: in the building corridors, entrance lobbies, and contested communal terrains. Sport is an escape and friendship an extension of family. Women make fleeting appearances in what remain male-dominated spaces where gender roles are rigidly assigned. Le miroir (2006) illustrates the construction of iconographies and stripped agency. Bourouissa claims that he wanted to convey “a tension in the image.” Violence permeates, forcing a reflection on the boundaries and collision between individuals and state violence.

Bourouissa’s gripping and carefully crafted photographs are a critique of the media as much as of society. They convey mundane everyday scenes and extract humanity against external ignorance and prejudices. And little has changed in the past 15 years. Bourouissa’s portrait of France’s negligence and the broken promise of loving all its children equally remains even more pressing today.

Farah Abdessamad

is a New York City-based writer and essayist, originally from France and Tunisia