In times of financial and political upheaval—in which digital devices are an inherent and rapidly developing medium for both finding work and working—the ethical, personal and social concerns around the “gig economy” are more pertinent than ever. The likes of Uber and Deliveroo have been widely discussed (and criticized) for their treatment and expectations of workers. However, sites like People Per Hour, Upwork and Fiverr—platforms for people to tout anything from graphic design, illustration, screenwriting and translation, to legal consultancy, nutrition advice and spiritual healing—have been less closely examined for their potentially damaging impact on those relying on them for income.

Real Work, a current show at Liverpool’s FACT gallery, features a multi-channel reality TV-like video installation by New York-based artist Liz Magic Laser, titled In Real Life. The work presents the stories of five workers from around the world who use such platforms for work, highlighting the precarity of freelancing and also the cultural differences that make freelance work far more accessible for some than others (one Liverpool-based scriptwriter, for instance, never has to compete with a lack of electricity and faulty generator like his Africa-based animator counterpart). The work is shown alongside Sweat (2018) by Candice Breitz, with both pieces looking to highlight unheard voices of workers whose employment is frequently unreliable, deregulated or, in the case of Breitz’s piece about South African sex workers, dangerous and stigmatized.

“It’s like with any Internet surfing rabbit hole—but you’re online shopping for labour”

Liz Magic Laser worked with a life coach and a spiritual advisor to create her piece, to offer advice to the other five workers around self-care, creating a personal programme for each with “biohacking” tools with the aim of improving their quality of life and work. The stories are presented as experimental documentaries in a ciricular installation that creates a sort of physical community of virtual, remote workers; many of whom discuss their feelings of alienation, frustration and loneliness. I spoke with the artist.

What was it that interested you in making a piece about the gig economy and freelancers?

It came out of a specific prompt from FACT about the future of work; which was related to Liverpool’s history of unions, and dock workers’ rights. I was struck by the odd communications I had when using these gig platform sites myself over the last few years; the first time I used Fiverr was to test a child’s voiceover to see if that would work for a project [2015 short film Kiss and Cry]. Obviously you’re corresponding with the parents to give direction about the tone or intonation of different words and it became clear I wasn’t going to get a perfect result from this process. I confronted the issue that [on such platforms] you’re prohibited from speaking with someone on the phone—there’s safety measures in place to keep everyone anonymous and protect the profit. There’s an inherent dehumanization with that, as people are functioning in a more mechanical manner and you never know when you’re hiring if you’re speaking with an individual or a team of three of twenty people.

“I think there’s a perpetual teenage behaviour associated with being an artist”

There were various other instances—I used Fiverr or Taskrabbit for things like getting a transcription done quickly. It’s like with any Internet surfing rabbit hole—but you’re online shopping for labour, and most of that’s creative professional services. There’s a funny recognition, as I have a similar experience as a creative of sorts. It was an odd experience that sparked something for me; and I’d been toying with thinking about reality TV methods for the last five years, too.

Why did you specifically choose the life coach and the Tarot reader roles?

It was important that it was a biohacking life coach, as this piece focuses on the role of tech in one’s life and work. [Biohacking] is something that’s grown out of Silicon Valley and tech entrepreneurship, and from my point of view it’s tech solutions for tech problems—fighting fire with fire. The biohacking approach is very much about using apps and low-cost self-care and healthcare methods like FitBits to regulate or self-regulate your relationship to the machine so that you have a healthy, balanced relationship with it. Instead of it mastering you; you use the tech to master it and yourself so you can maximize your productivity in the least amount of time.

“Remote video chat on the one hand is more detached from reality; but on the other it’s very intimate… You’re aware of your own performance”

Then [the Tarot reader] was the yin to the yang, and a good counterbalance for that. It’s more of a pre-tech form of wisdom and spiritual advising; but something quite ubiquitous that we’ve always done in person—an older school form of wisdom that’s now administered remotely. The remote video chat on the one hand is more detached from reality; but on the other it’s very intimate—you’re used to doing that with people you know well, and you’re very self-aware when you see that little picture of yourself. You’re aware of your own performance.

What’s your own experience working with people like life coaches?

I see life coaching as a therapeutic practice, and this is the third project I’ve done with therapists of sorts. I totally suspended my disbelief and went for it—somewhat in service of the project, but suddenly I was doing mediation apps and things. It doesn’t matter why: you’re just living it, and then that allowed me to be the accountability partner in taking on the role of the reality TV producer, directing [the participants] about what areas to explore with the coaching; and coming up with ideas myself about things like what tech devices to use for each person.

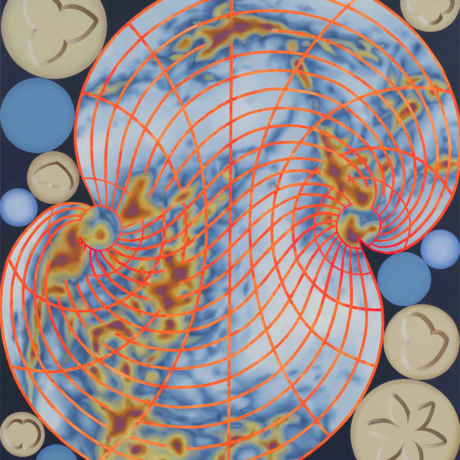

- Liz Magic Laser, In Real Life 2019, installation view at FACT. Photo by Rob Battersby

How did the project alter your own views on things like biohacking and the gig economy?

I still have an ambivalence about biohacking: it offers tools that are quite effective and can be used to improve your sense of wellbeing and productivity, but by the same token there’s something insidious about the need for it. The situation that’s unclear is if you’re becoming your own boss, or outsourcing your management to an algorithm.

With sites like Fiverr you’re scored on things like “You respond within an hour! You’ve made this much money!” There’s a lot of pressure to keep up ratings: it doesn’t make you feel as though you have a high level of agency. Not everyone can hire a nutritionist or a fitness trainer or an executive coach; but with the tracking apps you administer them on yourself and they have an addictive quality. Keeping up your ratings becomes intertwined with that feeling of self-possession—being in control, or being controlled by an app or online gig platform, which is potentially more sinister.

Thinking broadly about artists, how good do you think they are at practising self-care? It could be argued, for instance, that certain aspects of the art world perpetuate unhealthy habits, like a very normalized drinking culture.

The structures in place [in the art world] are very not dependable: you’ll often be corresponding with people who are being paid a salary to correspond with you, so they’ll write endless emails to figure something out—and while you might be getting an artist fee, so that feels legit, there’s a big spectrum across whether you feel beholden as an employee because you’re being paid decently or not.

But in terms of artists and self-care, it varies wildly, and you can’t make generalizations. It’s complicated: I think there’s a perpetual teenage behaviour associated with being an artist—like you still “act out”—but then it really takes all kinds.

Real Work, by Liz Magic Laser and Candice Breitz

Until 6 October at FACT Gallery, Liverpool

VISIT WEBSITE