My culinary tastes as a child were limited as a fussy eater, but for some reason when it came to the food I saw in cartoons, I loved everything I saw and wanted to eat it immediately. I was so captivated by it all that even the weird gloop of grey stuff during the memorable rendition of Be Our Guest in Disney’s Beauty and the Beast got me clawing at the TV.

Perhaps animated food looked more delicious to me than the real thing because these versions of food are their most idealised iterations. Think back to the glorious strings of cheese that featured on the pizzas in A Goofy Movie, as well as in any episode of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. When cheese stretches in real life it looks more like a cartoon than reality, exaggerated to the point of absurdity.

- A Goofy Movie, 1995 (left); Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, 1987-1996 (right)

“In cartoons you have the ability to exaggerate specific details, which lends itself nicely to the food category,” says designer Ross Norman, creator of the Instagram account @SpringfieldCuisine, which is dedicated to the documentation of dishes that feature in The Simpsons. “Like making sure the light is reflecting off the food to make it look that more delectable, or adding extra water droplets, or a slight steam effect, so your mouth salivates just that little bit more.”

“In cartoons you have the ability to exaggerate specific details, like adding extra water droplets, so your mouth salivates just that little bit more”

Norman has been running his Simpsons food account since 2017. With nearly 50k followers, it seems he’s not the only one who’s spent time drooling over the show’s glazed donuts and juicy Krusty Burgers. The unique aesthetic of the Simpsons has brought about many Instagram accounts that focus on one element, but with Springfield Cuisine, Norman has tapped into a stream of nostalgia as well as mouthwatering creations.

“It’s the humour, nostalgia and simplicity all in one place,” he says. As an avid lover of The Simpsons as a whole, Norman is able to relive very specific moments from episodes he remembers watching as a kid by selecting stand out foodie moments. “A lot of my own cartoon food references are ones that stem from childhood as that’s when I watched cartoons the most. But the nostalgia feels deeper than just a fond memory and it’s more about that feeling of discovery, seeing foods, mostly American, that I’d never seen before, and The Simpsons is the perfect territory for this.”

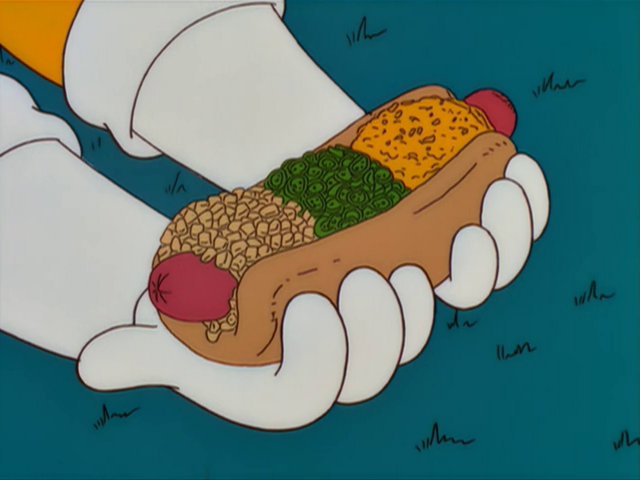

Norman’s top three Simpsons foodstuffs include Homer’s Nacho Hat, his Moon Waffle and his 35-calorie rice cake from season two, in which he loads up a rice cake with cheese, meat, lettuce, more meat and olives. Though these creations are a bit gross or excessive, for Norman, the beauty in cartoon food is that it doesn’t always have to be realistic to seem delicious.

“It actually helps emphasise a certain meal,” he says. “A prime example and one of my favourites from The Simpsons is The Giant Sub, Swimming in Vinegar (S8E17) in which Bart orders a megalithic sub sandwich, dripping in vinegar under Lisaʼs name that takes five people to carry in.”

- Screenshot from The Simpsons, Giant Sub (left); Isotope Dog Supreme (right)

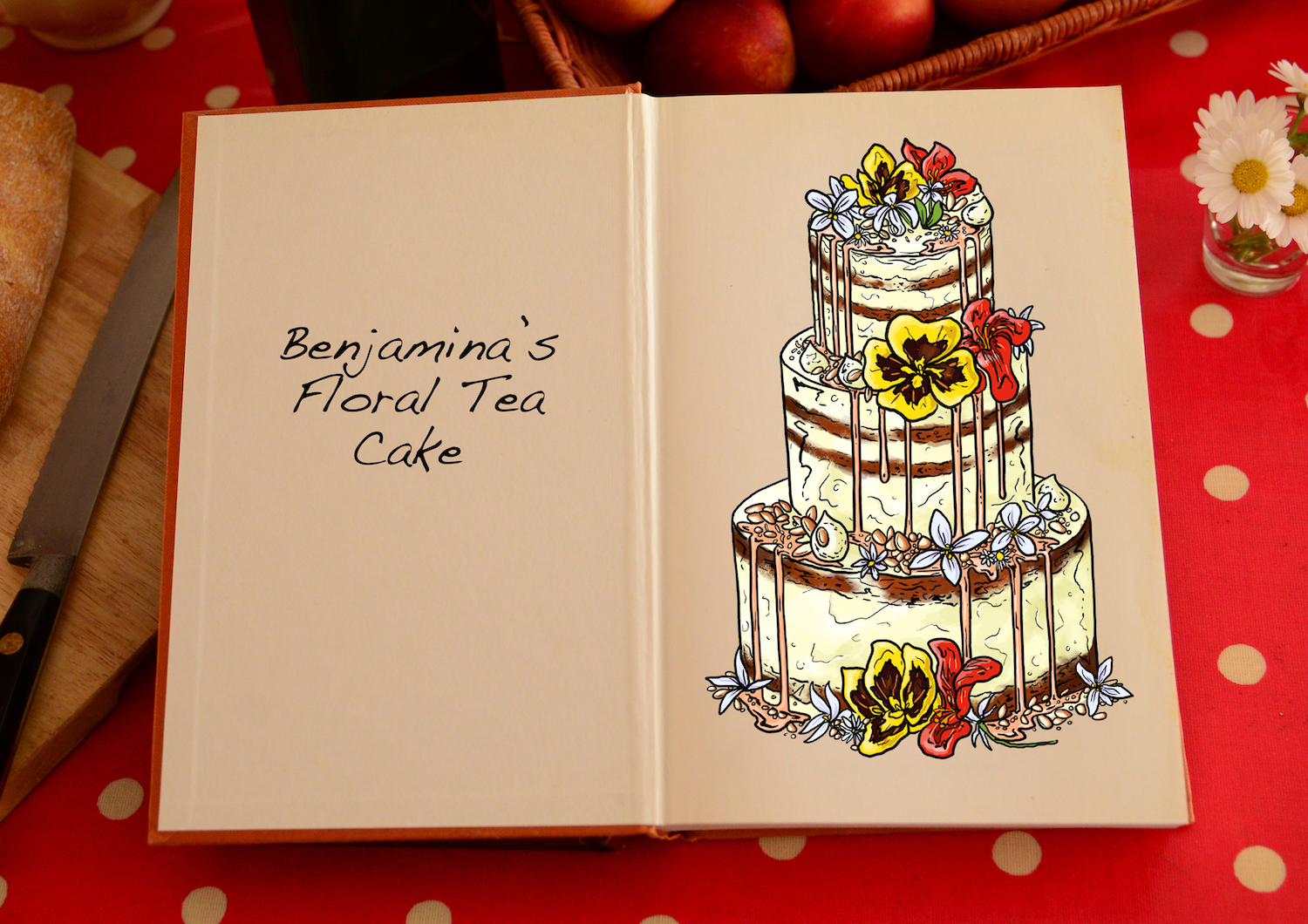

Of course, the designer’s account is not the only one dedicated to cartoon food. It is clear from many of these Instagram and Tumblr tributes that the food most lusted over is often junk food, or indulgent dishes that seem tricky to put together or especially extravagant. It’s perhaps the reason why so many people fawn over UK-based Tom Hovey’s illustrations, the man behind the official Great British Bake Off illustrations seen on screen. Since the beginning of the programme, Hovey has made viewers drool over his drawings of smoothly iced cakes and buttery, flaky pastries.

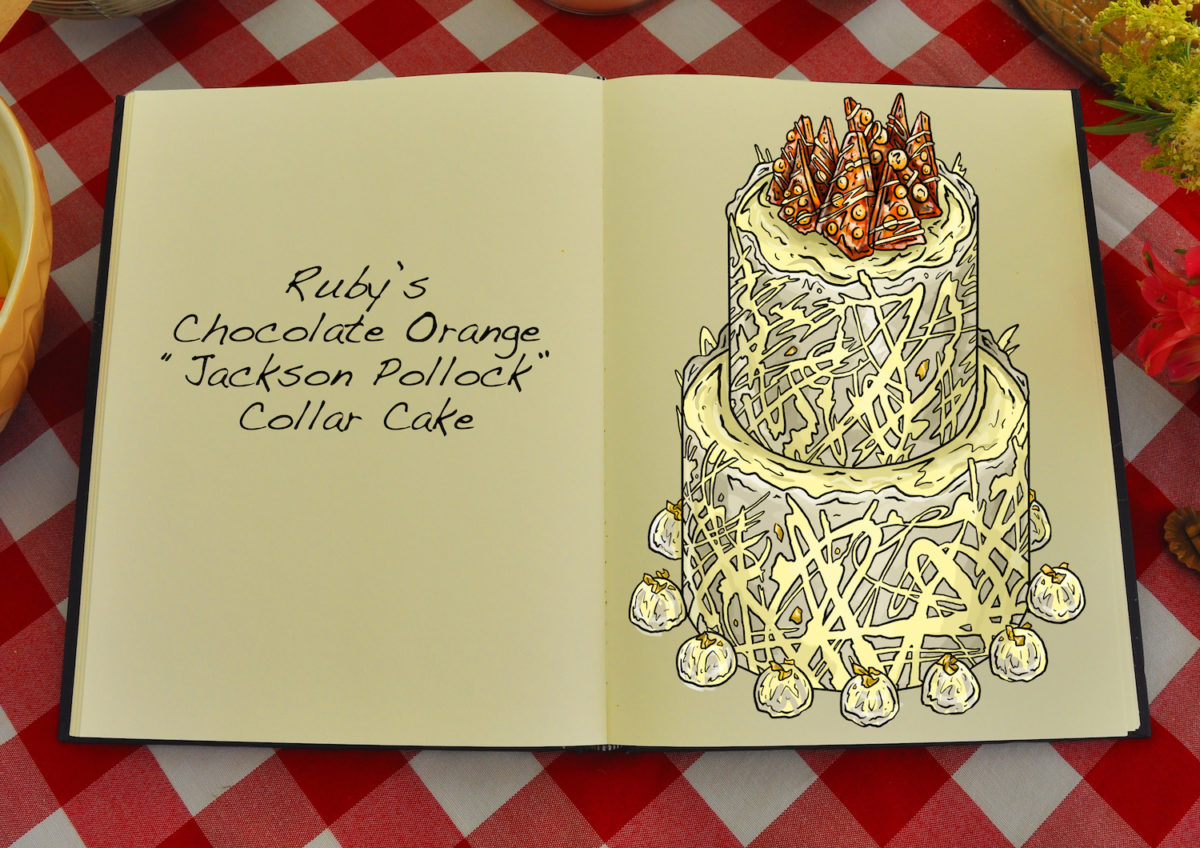

“My personal approach to illustrating the Bake Off bakes has always been to make sure everything is big, bold and beautiful,” the illustrator explains. “One of the main pieces of feedback I get from fans of the show is that my illustrations look better than the bakes, but that’s not really my intention. I’m concentrating on doing justice to the bake and to my style of presenting the bakes as pieces of art.”

“When looking at an illustration, you only have the visual sense—you can’t smell or touch it—so your imagination goes into overdrive”

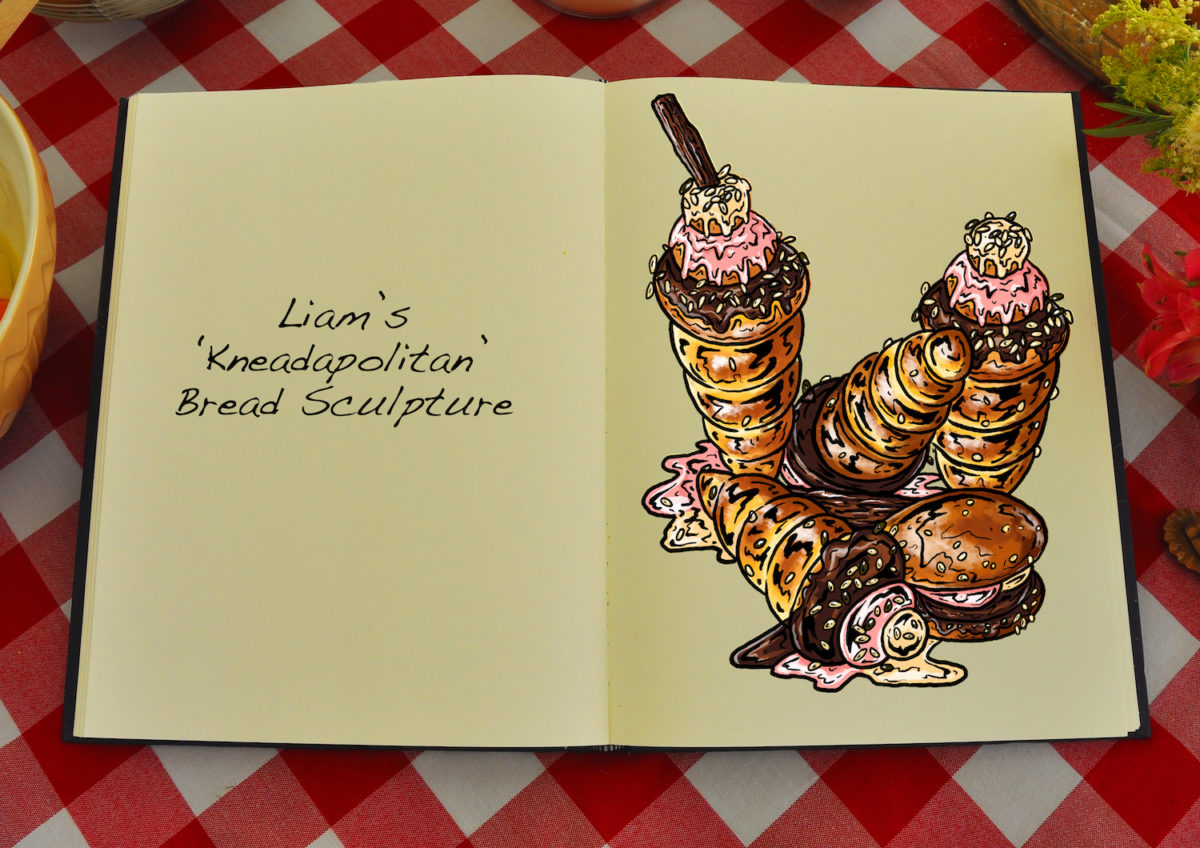

In contrast to the food on The Simpsons, Hovey’s images are more decorative and detailed—something that suits his brief of echoing the nostalgic aesthetic of the show. “The concept is to create drawings based on what the bakers might have sketched out when deciding what to bake in the show in their own recipe notebook,” he says.

While ultimately nothing can replace the real thing, Hovey sees the appeal of illustrated food as fundamentally rooted in its own restrictions. “When looking at an illustration, you only have the visual sense—you can’t smell or touch it,” he says. “So maybe your brain starts filling in the gaps and your imagination goes into overdrive, imagining how it might smell and taste without ever being able to do it.”

- Tom Hovey, Liam's Kneadpolitan Bread Sculpture. Great British Bake Off Series 8

- Tom Hovey, Ruby's Chocolate Orange Jackson Pollock Collar Cake, Great British Bake Off Series 9

For Hovey, his food illustrations, which have become a part of his practice beyond just Bake Off, are a chance for him to create representations of food that people might want to hang on their wall rather than just eat. “We can be a lot more fanciful and creative in displaying what sometimes can be pretty ordinary things. That is part of the challenge and fun of the job,” he says.

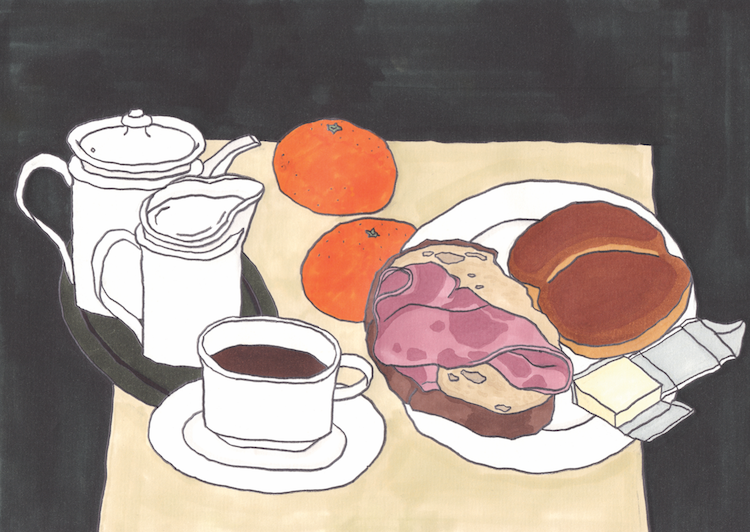

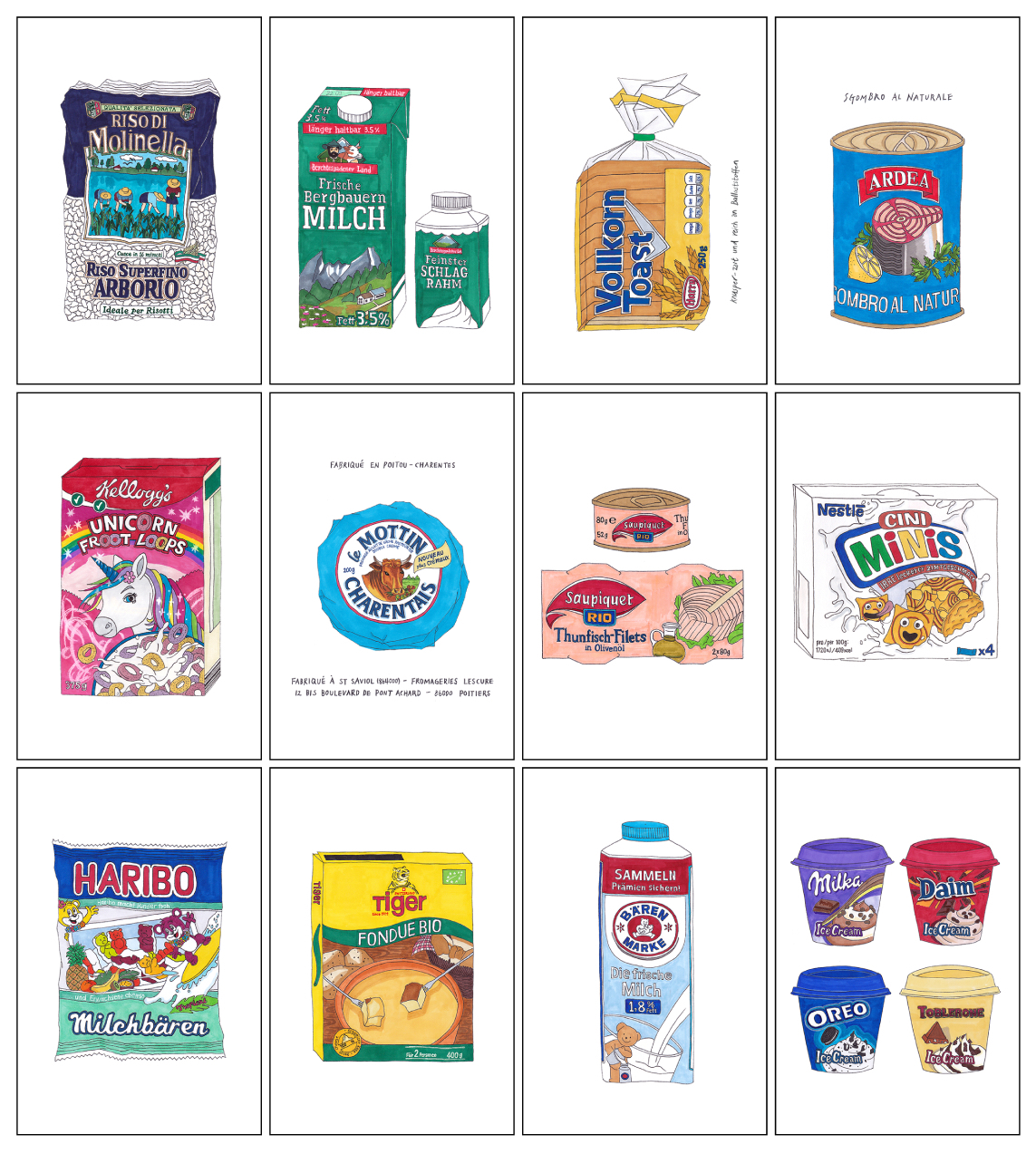

The room for creativity within everyday food is exactly why South Korean illustrator Sein Koo became drawn to the art. “I have always enjoyed looking at things that you find in the kitchen every day, such as food (especially sweets), groceries, small tableware like cutlery, dishes or jam jars,” says Koo. “So much so that when I travel to different countries, I spend a lot of time at the supermarket to look at different products.”

Koo began illustrating six years ago when she wanted to draw things she would want to colour in, having become tired of the adult colouring books that were being published in Korea. Eventually, she started illustrating the packaging of her favourite snacks, candies and instant noodles.

Koo likes to elevate the everyday in her illustrations. She does this by depicting her breakfast, lunch or snack, paying special attention to colour harmony. “There are more red-yellowish coloured foods than we might expect, like soup, bread, meat, and fruits,” she says. “So, when I am colouring even a piece of bread, I test a number of different colours beforehand to determine whether the soft beige part of the bread will go well with a reddish shade of brown or a darker, calmer shade of brown.” This attention to detail creates delicious images of simple feasts, with each object emphasised by Koo’s thin black outlines.

Koo also likes to illustrate branded products like Oreo packets and Haribo. Even in these, there is something delicious about her tiny, drawn morsels of recognisable food. “When illustrating objects that are packaged and well known, I can be fully focused and indulge in the art of drawing rather than being creative,” she says. “I do not need to worry about whether a colour will go well with another, instead, all I need to worry about is whether the colour I am using replicates the colour on the packaging. This is great because expressing my favourite objects with my drawing style is a delight in itself.”

- Sein Koo; Breakfast (left), Food (right)

“Animated food often appears more delicious than the real thing because of our ability to ‘taste’ things visually”

Similarly to Hovey, Koo believes illustrated food has the ability to look more delicious than the real thing because illustrators and cartoonists can’t rely on the other senses to convey the tastiness of an item. “When we see food with our own two eyes, even if every ingredient in the food is not visible, we can usually recognise the ingredients in it through our various senses and perceptions,” explains Koo.

“For example, when we order onion soup, we can identify what’s in it through taste, smell and other senses other than sight. However, if an illustrator draws an onion soup and paints a bowl covered with a layer of cheese, the audience will not be able to identify what is inside the layer of cheese. Therefore, illustrators will draw some additives that will communicate to the viewers that the illustration is indeed onion soup.”

Whether it’s a three-tiered cake, an outrageous hat made of nachos or a simple breakfast of fruit and toast, illustrated and animated food often appears more delicious than the real thing because of good old imagination and our ability to “taste” things visually. The exaggerated or idealised nature of some cartoon food, like overly stringy cheese or steam emanating from a juicy cherry pie, heightens these feelings and suggests that perhaps, one day, we might be able to achieve this level of perfection in real life.

It’s also down to our own personal associations with particular cartoon foods and the nostalgia conjured around them. These meals aren’t just cemented in my brain because they looked tasty on screen. Rather, they take me back to a time when I watched cartoons with giddiness, and tried to convince my mum to recreate the mammoth ice cream sundae from Rugrats. What could be more delicious than that?