‘We make around 90 per cent of our objects here in the studio. We hire people, but we oversee the process. In Cuba we lived in a kind of glass jar where we manufactured things in Brazil and by the time we had the chance to see the work it was too late if we didn’t like it, so we had to accept many pieces that weren’t really the result of our decisions. In 2003–04 we decided we did not want to do more work that we couldn’t supervise or intervene in. So coming here has been wonderful. We have also found a country in crisis and this is a situation in which we know how to manoeuvre because Cuba has been in crisis throughout its life. We managed to get good prices for things, we found enthusiastic people to work with us – these are not apathetic people enjoying a booming economy; here people need to make things and we all have a common goal. In that sense, for us the crisis has been a blessing. I think there’s something good behind a crisis. The limitations generate a good energy and the intention to change things.’

There were originally three Carpinteros: Dagoberto, Marco and Alexandre Arrechea. ‘We studied together at the ISA, at the Instituto Superior de Arte, which comes at the end of the degree course. The education system in Cuba is very long. It’s like studying to become a priest. That’s what my dad used to say’, Dagoberto laughs and continues: ‘In art, there are elementary, middle and upper levels and the upper level is taken at this single institute in Havana [the ISA], so all the people who have been studying in the country come together there. From the very beginning you’re trained as a draughtsman and I remember that at the time there was a big influence from the socialist countries and a strong emphasis on life drawing. You were forced to do portraits and you had to do them well. Can you imagine the amount of drawings that were made at that time?

‘One of our teachers was René Francisco, who had this concept of pedagogy not as a vertical but as a horizontal discipline in which the teacher is another student. As a result we became something of a jazz ensemble where he would give us a theme and the students would develop it. The theme of that year was the Self and the Other. René was fascinated by this idea of Otherness: the philosophical idea of the shadow out there and how you incorporate it in your art. As part of that, we started working, interpreting and translating the ideas of another person. From that one exercise we accumulated so much work that we had enough to go on for another year and another year and so it’s been like the tale of Scheherazade: 20 years have passed and we are still working on it.’

That initial exercise was based on the furniture in the place where they were studying, an old country club in Havana. ‘It was a very exclusive place before 1959 and we wanted to do something related to that environment. The pictures that came out of that era were very strange, they looked like an interpretation of 19th-century painting. We used some techniques that made the work look like it had been painted a century earlier but the issues were current and we took advantage of some of that double meaning.

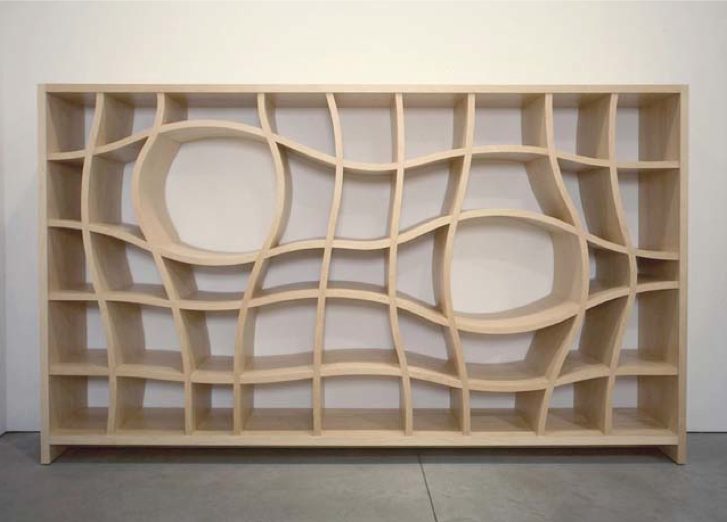

‘We still carry out the same kind of research with all the objects we do and that’s why we love both industrial production and design objects. We believe that in all these objects there is somehow a human trace. We never use the human figure in our work, but there is a human trace in it all the same. That’s one of the pillars of our work, especially because today’s world is so object-rich and everything is based on the things that you have and what you own. We think that the language of our work must somehow be based on that world. If you want to send out a message, you have to do it without people noticing, using the things that people already have around them.’

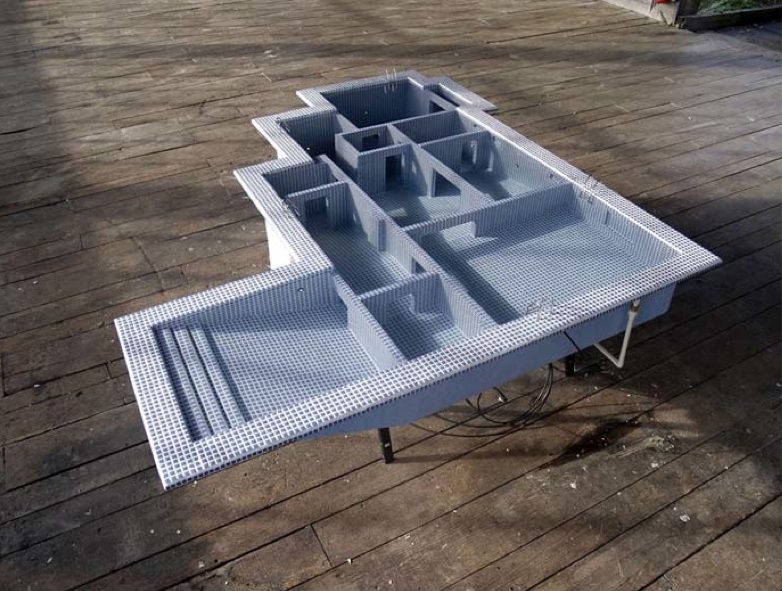

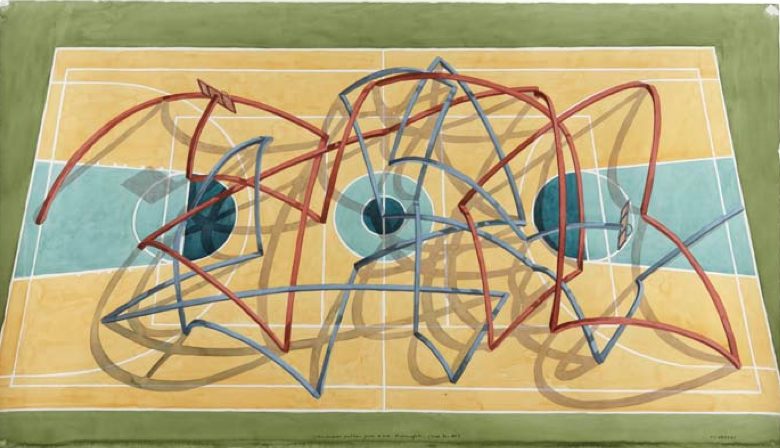

This research into objects and their functionality has been a constant in their work, and it is by changing ordinary objects – their size, placement, materials – that their playful transformations take place. They believe all objects have a language or code, and their strategy is to use this code to generate a new meaning. A bed can become a roller-coaster or twisted highway, a pool turns into an aircraft carrier, or a basketball court is transformed into a sculpture in which the bounces of the ball have been translated into blue and red arcs as if telling the story of an earlier game.

‘There is a strange thing with art’, Dagoberto says. ‘Any work of art in a gallery or art institution is automatically killed. It’s no good for anything else, it only serves to generate language. Even when that language reflects the functionality of things, the fact that you put it in a gallery makes it an object of worship, useless–you’re killing it somehow.’ Working in that no-man’s land, blurring the lines between art and functionality, their work is an exercise in absurdism that can’t fail to put a smile on your face.

People already referred to them as ‘the carpenters’ while they were still studying because they liked working with wood and made small pieces of furniture, so when they were invited to participate in a biennial in 1994 and had to decide on the group name, it seemed natural to stick with the moniker, with its suggestion of traditional craftsmanship. It wasn’t a very ‘art world’ kind of name. ‘It was like we were spies – as though we weren’t really in the art world, not the real thing. That put us in a very advantageous position in allowing us to make any comments and any objects we wanted. I think it was somehow a gateway for our work – a way of seeing things without an art theory book in hand, but with more of an outsider’s point of view.’ Of course, unlike carpenters, their creations don’t have any functional value, give them a greater freedom in their work.

Working together has become second nature to them, to the point where they can no longer conceive of working individually. ‘I tell Marco that it is a binary code: yes and no, this thing goes, that one doesn’t. It’s like that all the time. It’s like going to therapy. Most of our work is somehow a result of our relationship. It’s also an exercise in interpretation and misinterpretation, because many times we don’t understand each other and one of us has a completely different picture of what the other one is thinking and what results is more interesting than the original idea! I believe that creation is something collective, something to share, a gift you give to each other, and this is how we do it.’

Los Carpinteros have created a micro-society with its own rules and limits, a tiny independent democracy, but Dagoberto explains that, since there are only two of them, they sometimes fail to reach a consensus and have to look to a third party to help them decide. At this point, I ask why Alexandre left the group: didn’t being three make reaching agreement much easier? ‘Although people work as a team I think there is a level of selfishness that is necessary to defend points of view or criteria’, responds Dagoberto. ‘For Alexandre, it was too defining and made him decide to leave. I think he didn’t want to share more ideas with us. It was very difficult because he was a partner with whom we had worked for 13 years, but we understood completely. We continue to have very good relations. We always remember that period fondly–a very mad period, we were young and there was an amazing energy.’

Marco arrives. He’s got a cold and hasn’t been feeling well, so I start wrapping the interview up. I ask them about the watercolours in the studio. Watercolours have long served as the basis of their work, a working tool to allow them to discuss ideas and work out issues prior to going into production. Over the years they have taken on a life of their own. Marco explains: ‘At some point most of the ideas in the watercolours were not being manufactured, so they became a kind of utopia and began to have an independent value for us. They were a conceptual fantasy, describing something that we would build at some point, or not. They began to break free from any commitment to making and we started to fantasize in them about things that were impossible to build. So they started growing independently until they became the watercolours that you see today.’ They are meticulous, detailed, large-scale watercolours and of stunning delicacy; some will become an installation or sculpture, while others will remain as impossible fantasies.

Marco explains their future plans. They have been experimenting with a new medium: film. Behind this departure lie the same obsessions, of course, but the pair feel it allows them to say things they can’t in any other medium. They still haven’t decided, and really don’t want to, whether the work itself should be classified as film, documentary or video art. ‘Do you want to see it?’ they ask. Of course I do. The three of us sit down in front of the cinema-sized screen hid-den behind a black curtain and it starts. It is a documentation of a conga performance in Havana but everything is planned, from the dance moves to the music, and there were at least a hundred people involved. It took a year of preparation. They are working on two other film projects and they seem excited about the results and the possibilities of a new medium – like children with a new toy.

In fact, they look excited and passionate about every – thing they do, putting all their energy into every project. ‘We don’t make a big effort to be funny, we just see things that way. It is very serious for us, but what happens is that some – how the work is a wink, a laugh’, says Dagoberto. After 20 years together, the secret would seem to lie in having fun and continuing to surprise each other on a daily basis. The results speak for themselves.