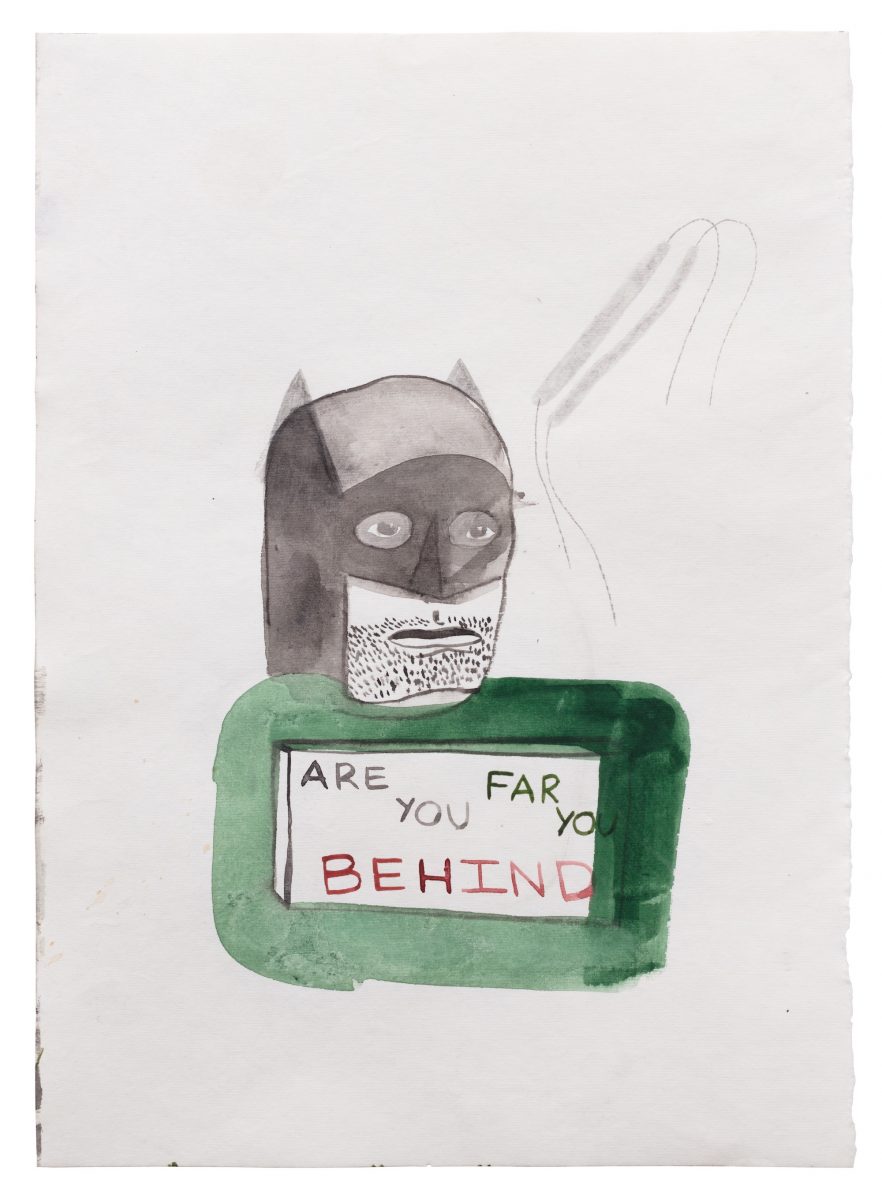

Before Rudolph Giuliani became part of Donald Trump’s personal legal team, he was widely admired for his mayorship of New York City from 1994 to 2001. Last year, Republican political strategist Rick Wilson compared his demeanour during this period to that of Batman (an often volatile but essentially good force for justice) before calling his recent descent to ignominy a “tragedy.”

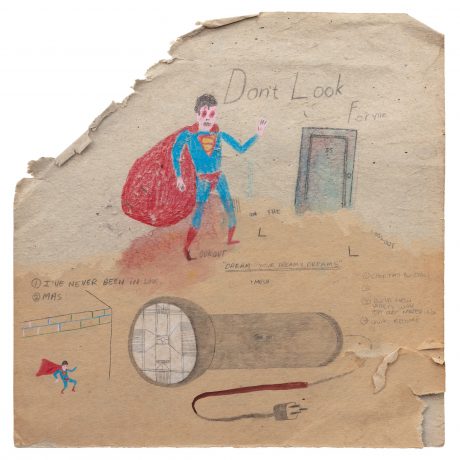

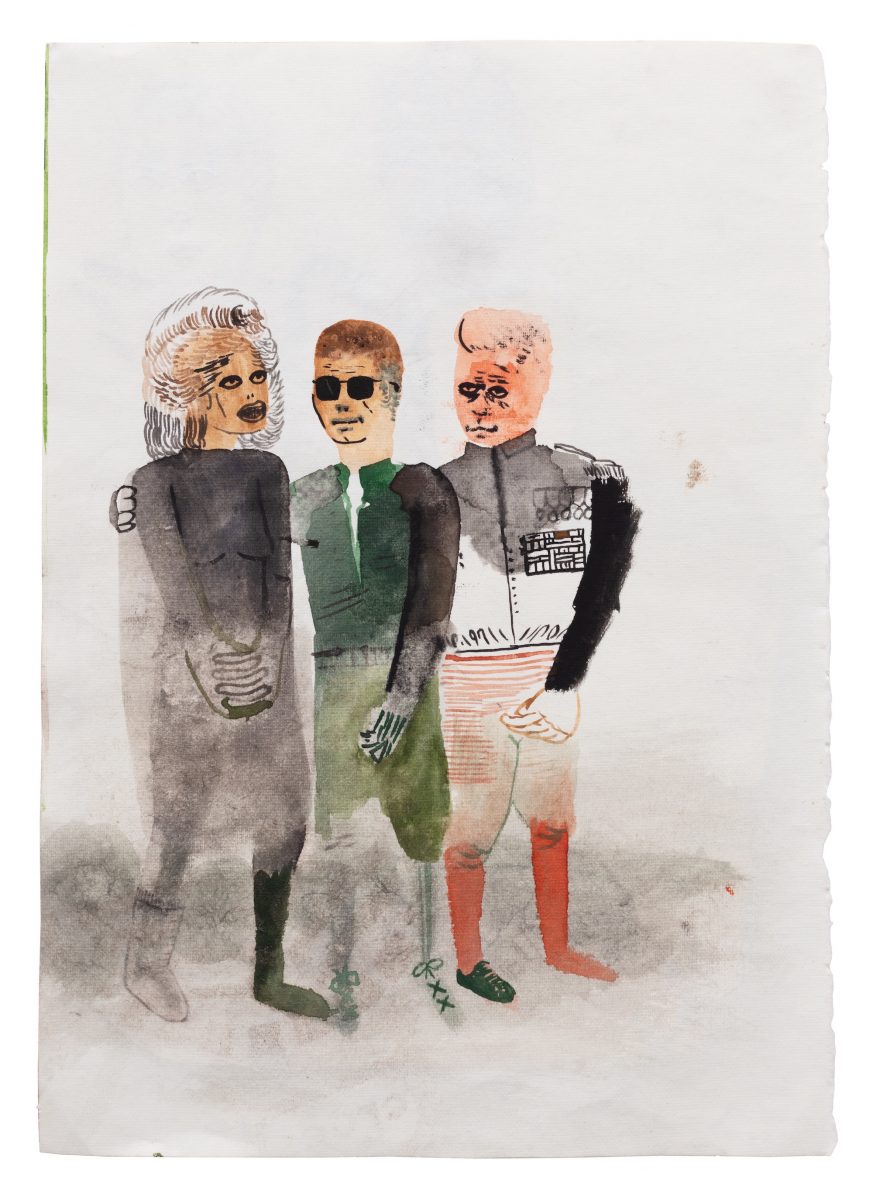

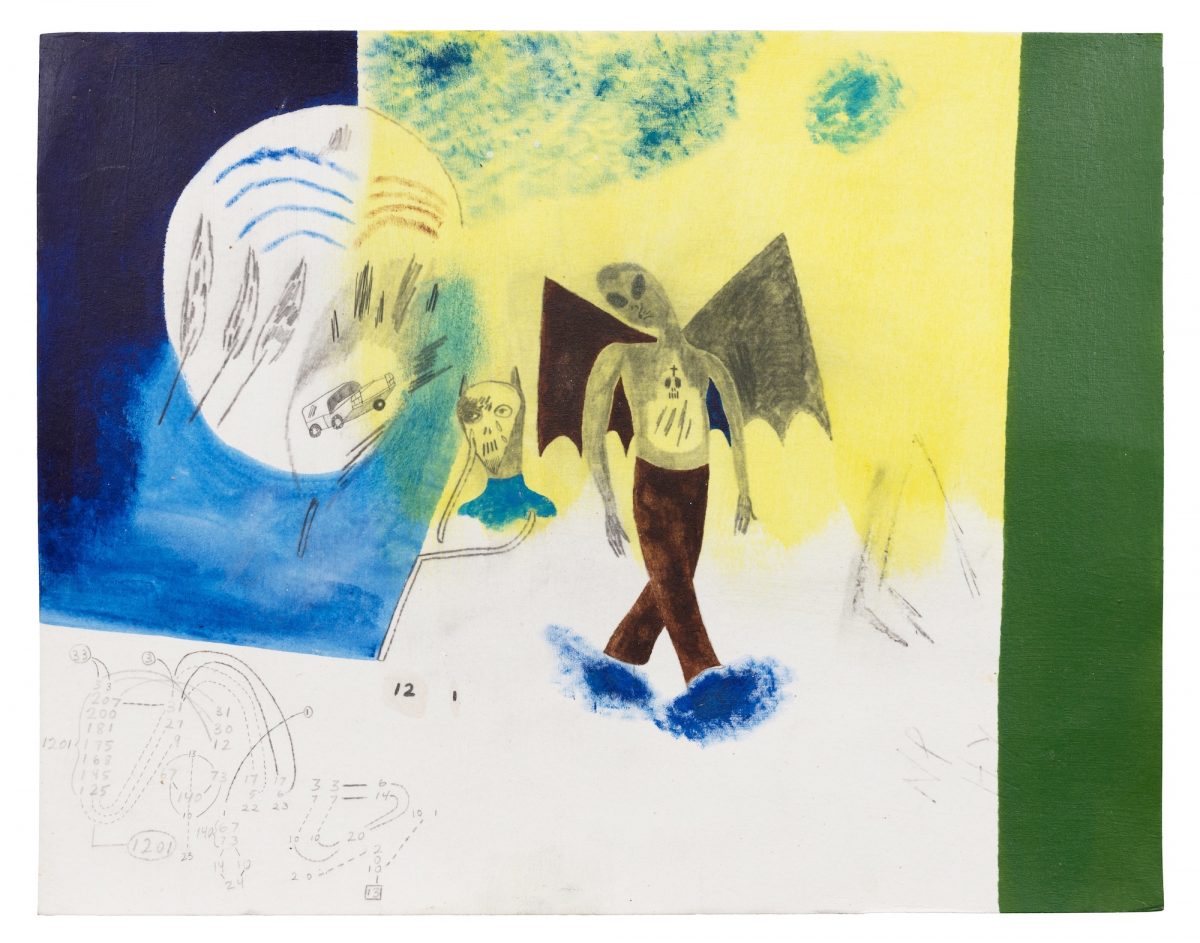

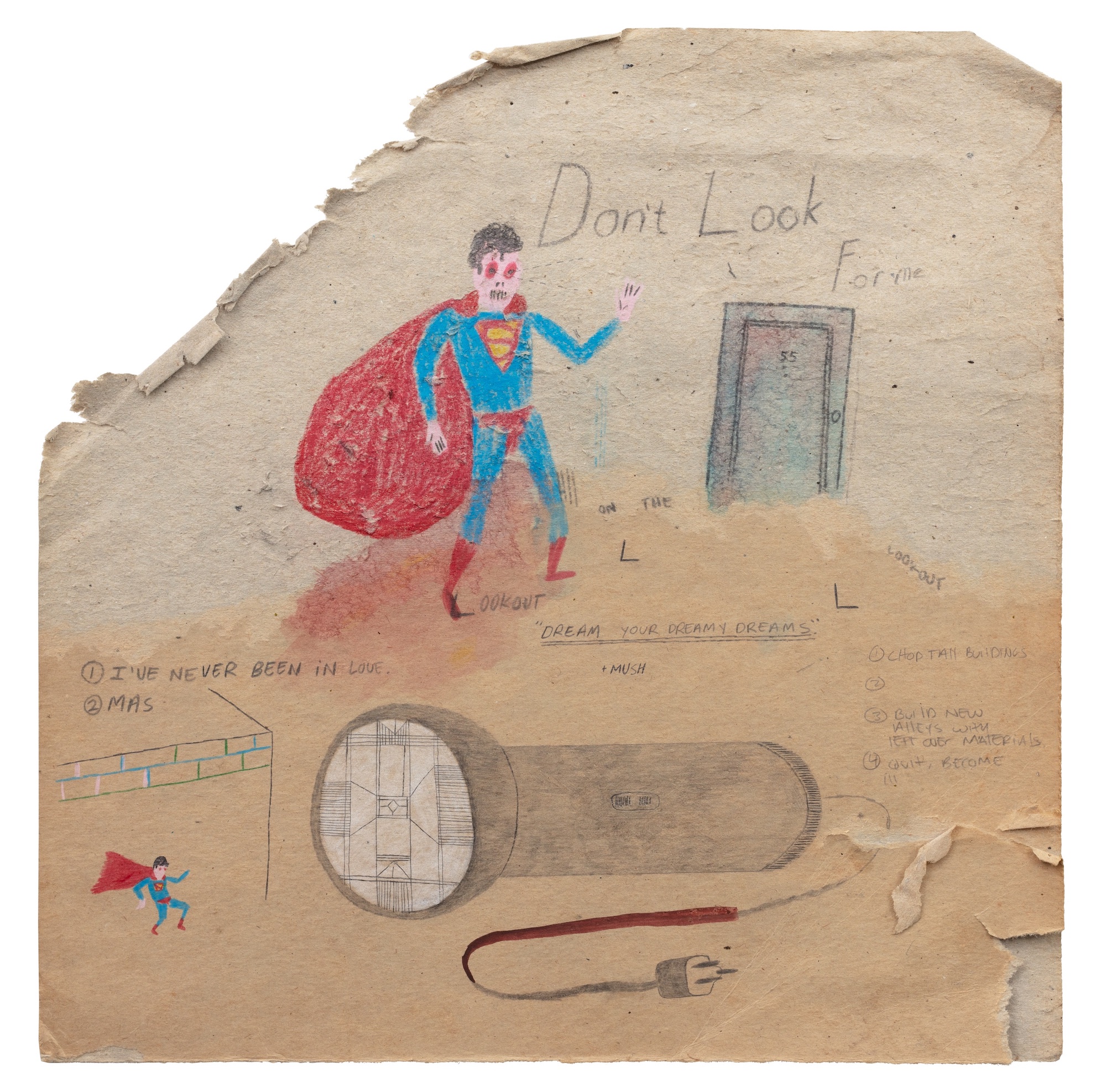

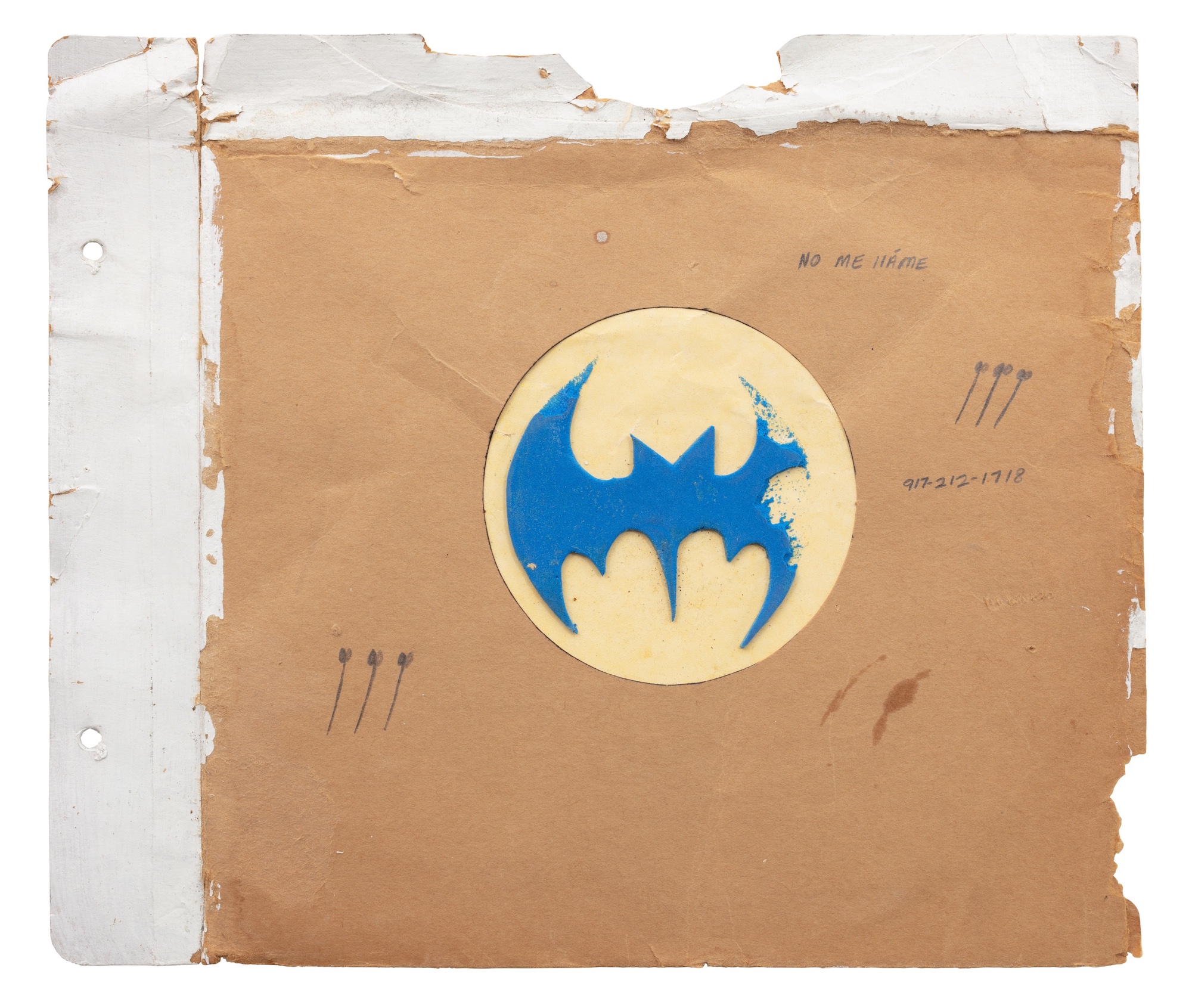

Kenny Rivero worked as a doorman in a luxury residential block in the city during Giuliani’s heyday, absorbing gossip, observing characters and “seeing who has a voice in the city and who doesn’t”. Giuliani figured prominently on newspaper front pages at the time, and now appears in a drawing in Rivero’s exhibition, Palm Oil, Rum, Honey, Yellow Flowers, at The Brattleboro Museum & Art Center (BMAC) in Vermont. In the piece, Giuliani’s face is etched under a drawing of Batman in a speculative fiction about racially-motivated factions in New York’s superhero community.

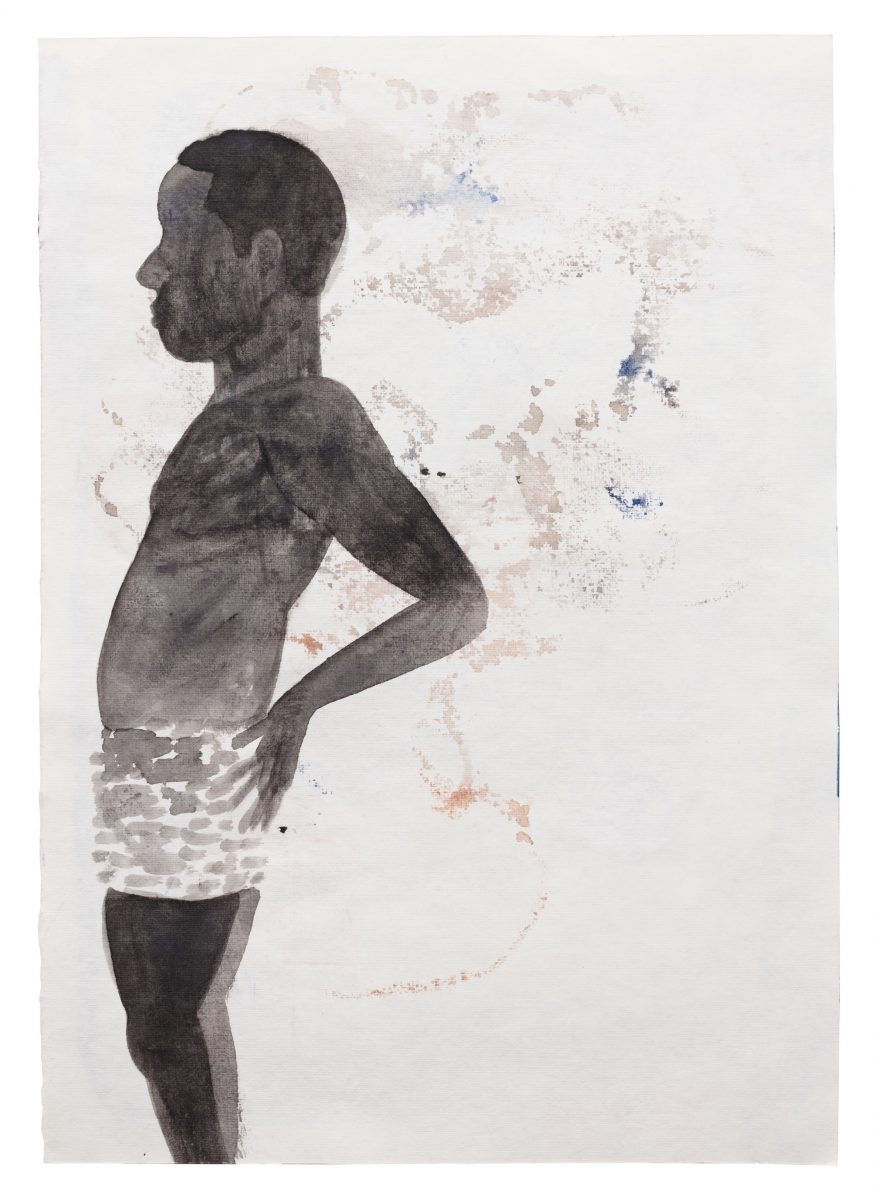

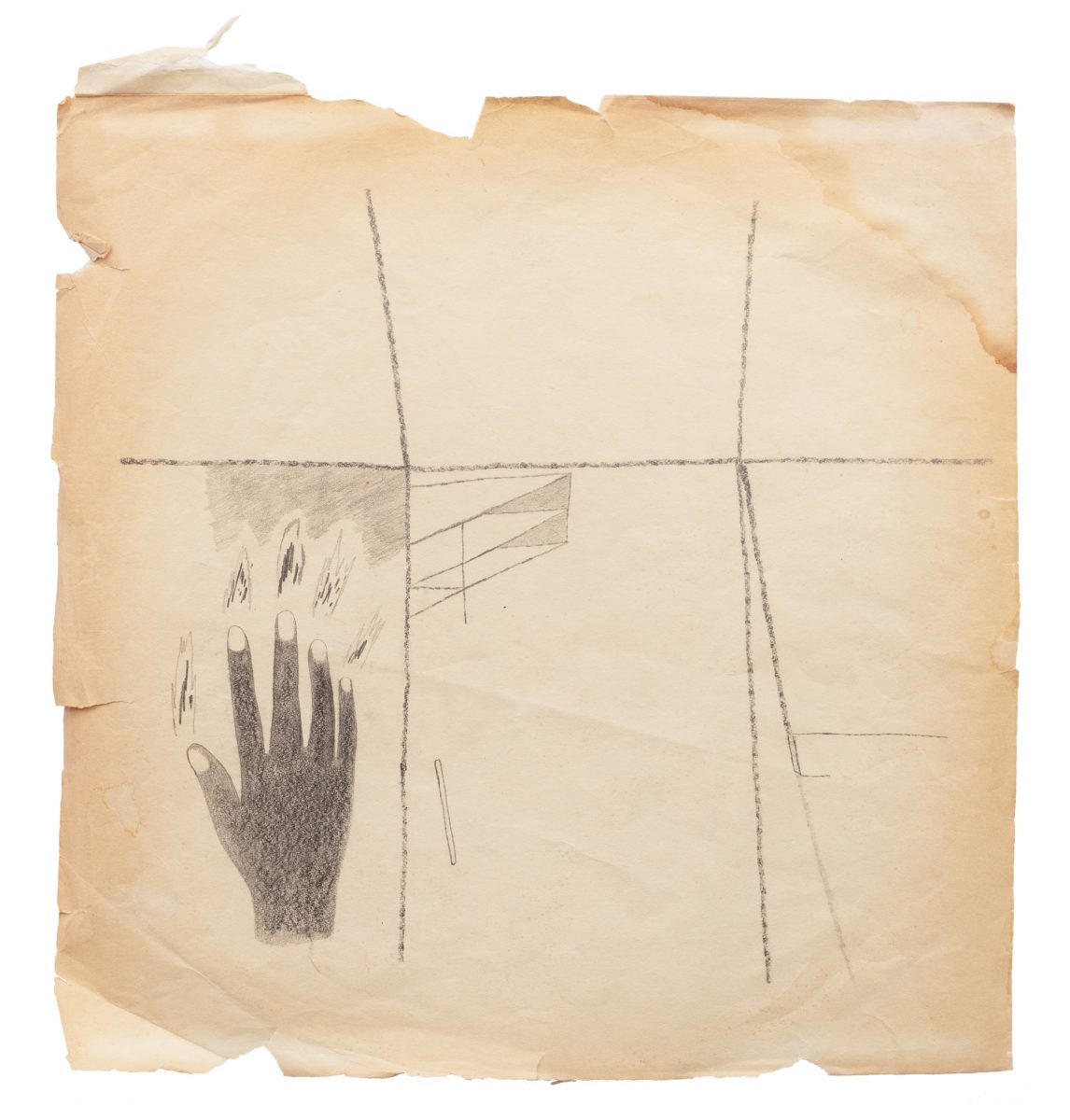

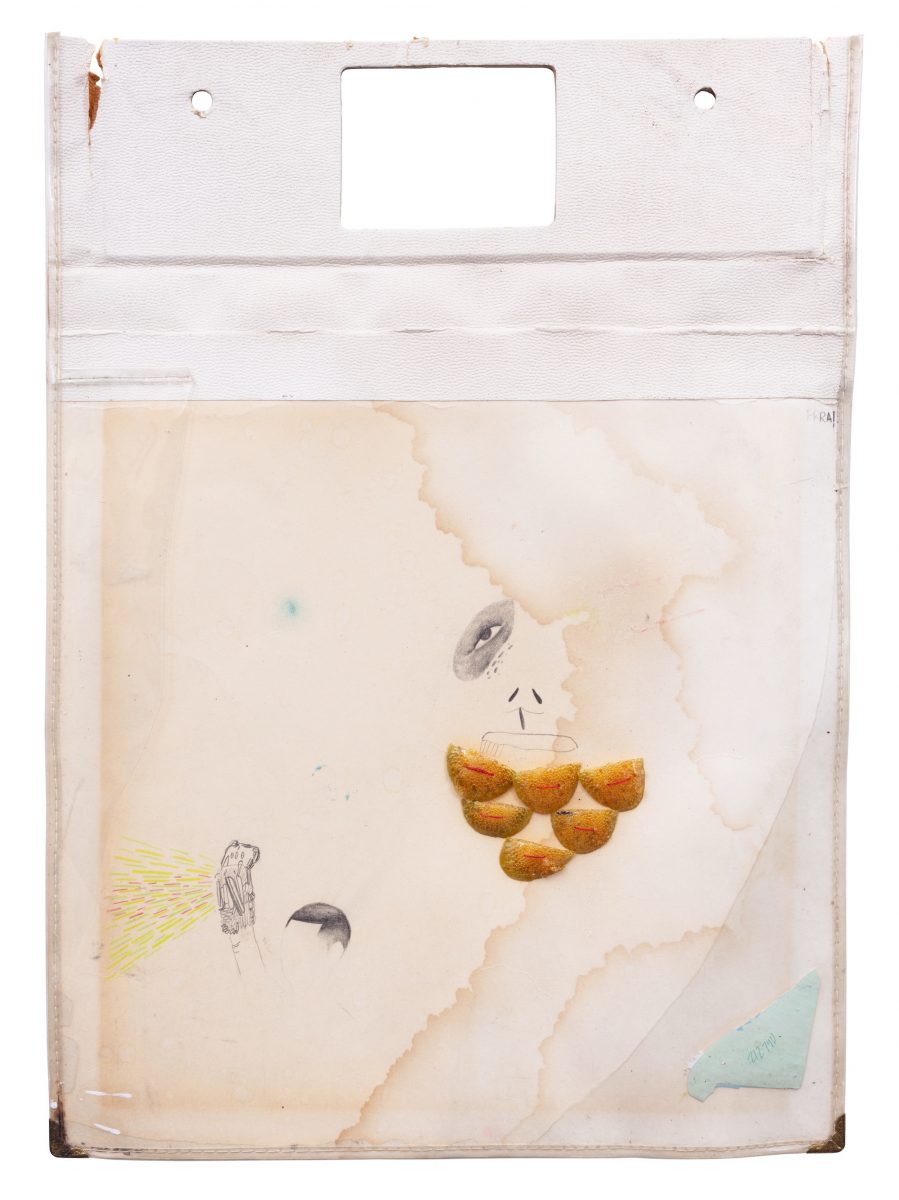

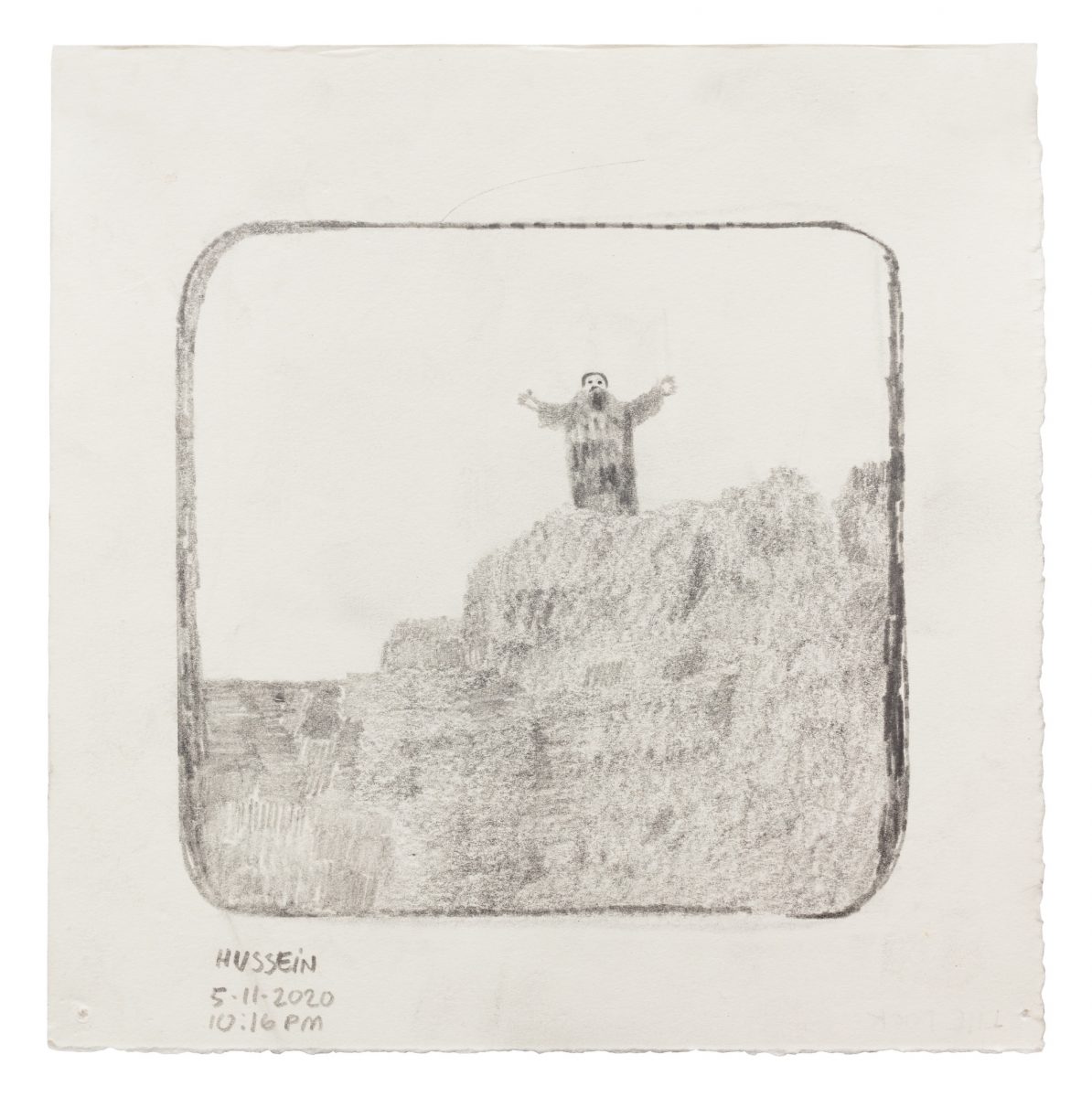

Notable for his use of found materials and unpretentious presentation, Rivero’s works are a series of chopped narratives, pithy snapshots and collage-esque assemblages of New York City’s everyday underbelly, studies of life at the feet and in the basements of its skyscrapers. Influenced also by summers spent in his ancestral Dominican Republic, Rivero addresses the Caribbean diaspora, belonging and masculinity in his work. It takes him a long time to create work using paper whose history he doesn’t know, saying, “It’s about this creation of a circuit between me, a potential future and a past that may not have been aware of me or me of it.”

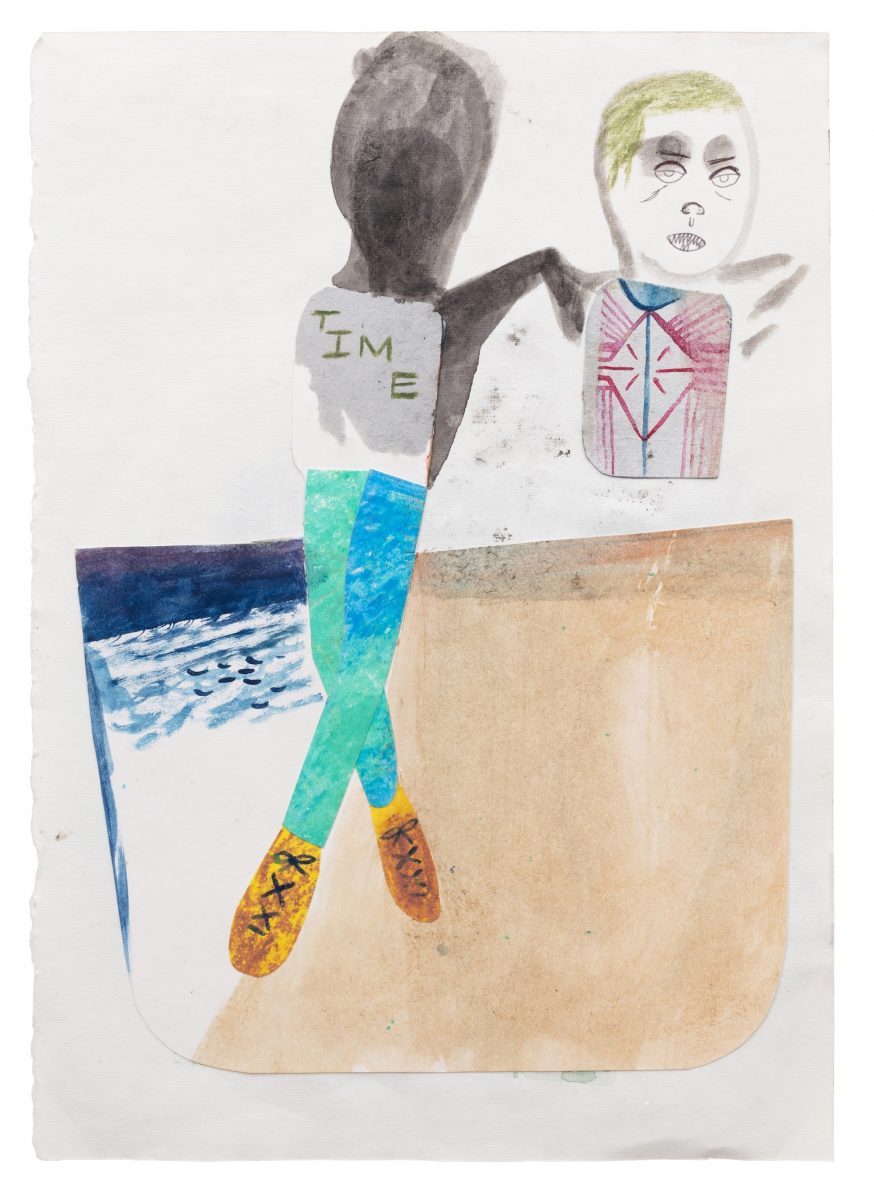

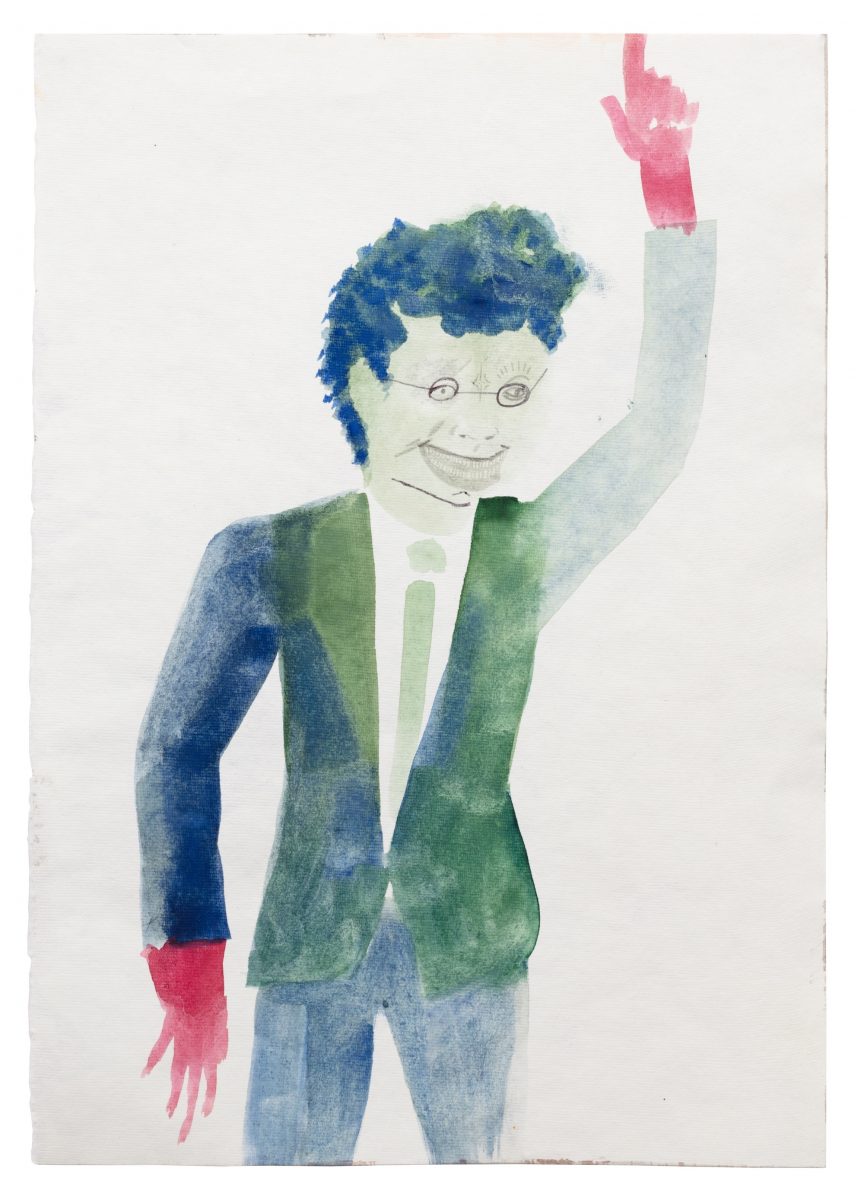

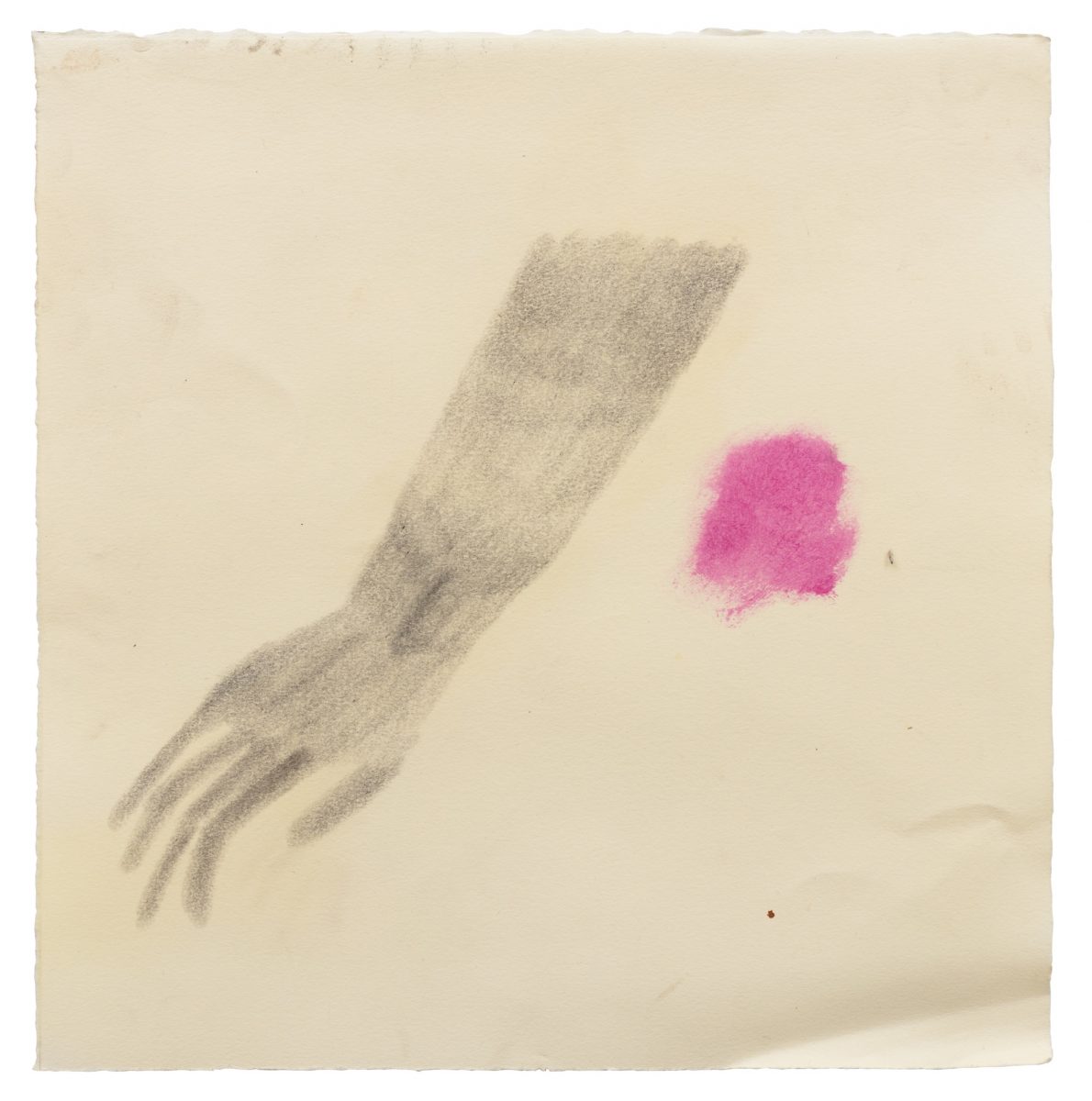

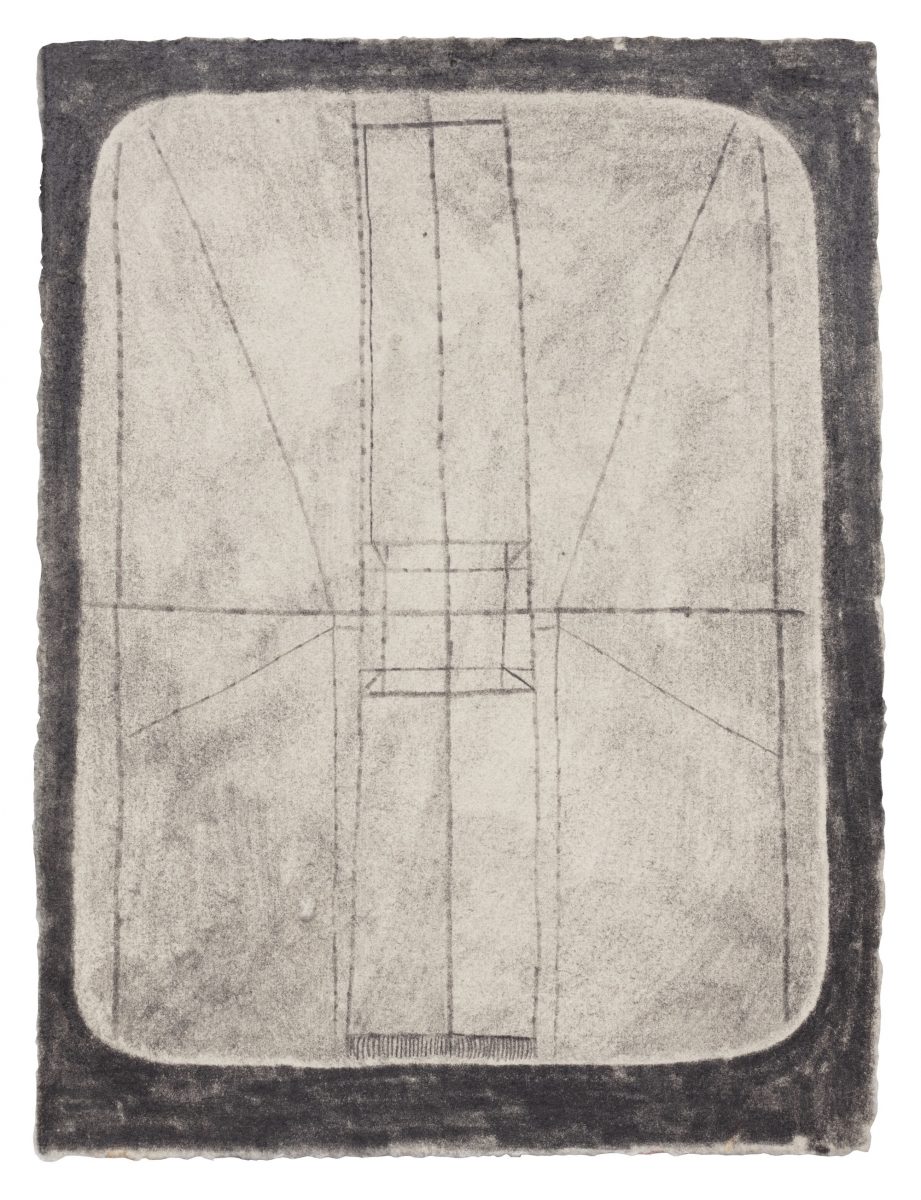

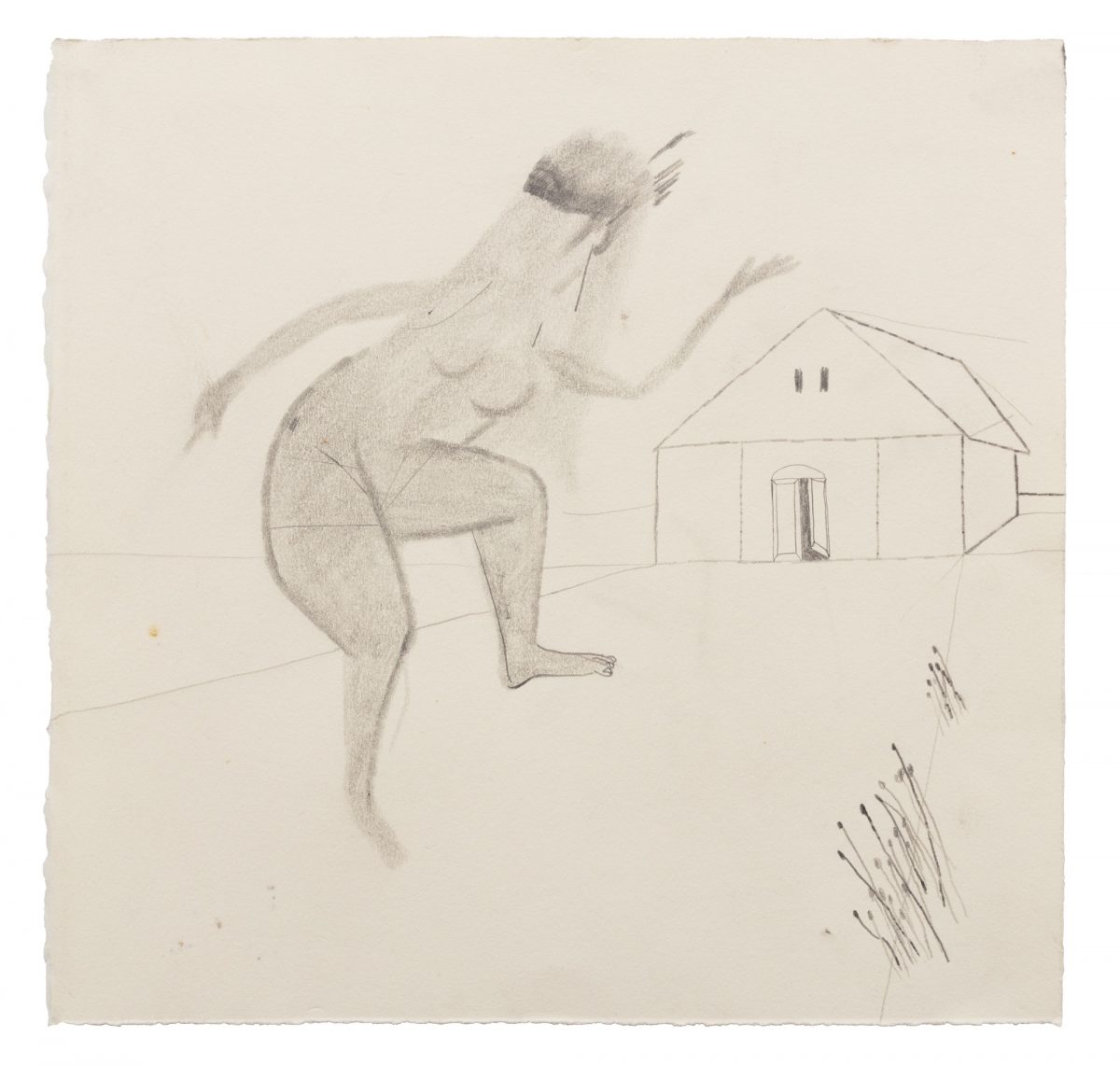

- Bather, 2016-2020 (left); Unexplainable Hazardous (Top) Time (Bottom), 2016-2020 (right)

This show is described as an “abstracted landscape informed by the people, architecture, culture and aesthetics of Washington Heights.” How would you describe the New York City we’re seeing here?

I think it’s a very private one. One of the things I’ve always found in my work is space to treat the city as an intimate place, location, entity. There’s this idea that New York belongs to everyone, it being a world city. So I think approaching it through this close intimacy is really important. It’s not necessarily about New York as this famous place, but it’s the detritus of New York, its remnants, these bits and pieces that I’m discovering, finding, salvaging from somewhere, and then re-energising to speak to stories that may not necessarily be prioritised in history.

I remember my mother telling me the story about hearing Malcolm X speak when she was younger. She would go to this theatre that only played Spanish-speaking movies. And in order to make it to the movie on time, she would sit in a sermon that happened beforehand: listening to this man speak but not understanding what he was saying, because she didn’t speak English at the time. So all these small little accidents that happen in New York that are really about close looks and engagements. The work and the show are definitely speaking to that. I spent a lot of time reading newspapers while working as a doorman. And I feel like a lot of my drawing also came from that, from these ideas that I was developing in terms of seeing who has a voice in the city and who doesn’t.

“It’s the detritus of New York, these bits and pieces that I’m discovering, finding, salvaging from somewhere, and then re-energising”

What does using found materials allow you to do that working on paper does not?

Being accountable for the paper and having the paper actually collaborate with me, and whatever image gets produced, is really important. It takes me a long time to draw something good on regular paper, and I think it’s because of that detachment, the fact that the material is missing history. It needs to have gone through some kind of event or process first before I draw on it.

When I was young, I used to kind of hide a lot of my drawings, because, other than for school, we couldn’t afford to buy paper. My brother was and still is a DJ, so I would take all the sleeves from his records, draw on them and put them back. I would draw on all the blank pages of my sister’s books and on the inside of cereal boxes. Then when I got an allowance, I would just buy sketchpads all the time. Eventually I started to collect things. My mother threw away her wedding album after I’d put the pictures in a new one. I freaked out, went through the garbage, found it and kept it. I continued keeping things like that, anything that happened to be paper.

In grad school, one of the big things that I was really into asking myself was: “Am I being intentional with every single material that I’m using?” And then thinking about the fact that paper bought from an art store has its own history, but it’s also treated like an anonymous space that doesn’t need to exist. Jack Whitten introduced me to this idea of plasticity, the idea of being mindful of the stretcher bars or canvas that you’re using, the idea that everything has a past. It’s always made by somebody, and it carries with it an energy. And then I put two and two together. I thought: “Oh, I could be drawing on these found papers. I could be drawing and actually connecting to the history of my family, the history of so many other things in the city that people are just throwing out the window.”

It seems that making work on a smaller scale is a consequence for you of that relationship with material. How else do you think about size and scale?

The spaces I’ve had to work in determine that. Right now, I definitely have the biggest studio I’ve ever worked in, so that obviously affects the paintings. I’m working on maybe 25 different paintings from the studio, and the scale varies from four by four inches to seven by six feet.

One thing that I try to be very careful with in the big paintings especially is for them not to always carry big painting energy, if that makes sense. It’s really about making sure that the bigger paintings could still feel intimate and still feel like they’re made on my lap. Scale is more about how much I am letting you view it, not how big something is. I’m trying to articulate it better, but I think there’s something to the small paintings feeling more monumental, and the big paintings feeling like they’re from a diary.

That extends to how the work is hung. Looking through it, there are tropes from pop culture, comic sketches, even storyboards. Do you think it’s fair to call your work satirical?

I think it is. I have a side-side-side practice of wanting to do stand-up. I’ve been working on a five minute set for like five years… but I’m not going to do it. One of the first things I ever wanted to do as a kid was act, I didn’t get into art until I was an undergraduate. Having transferred through different schools, I knew I needed space to engage an audience and talk about history, politics, gender, masculinity. I feel like the drawings have been that space for me. So I think there is some kind of satire in there, the space where I get to unpack and figure out and navigate these ideas that I’m testing and absorbing.

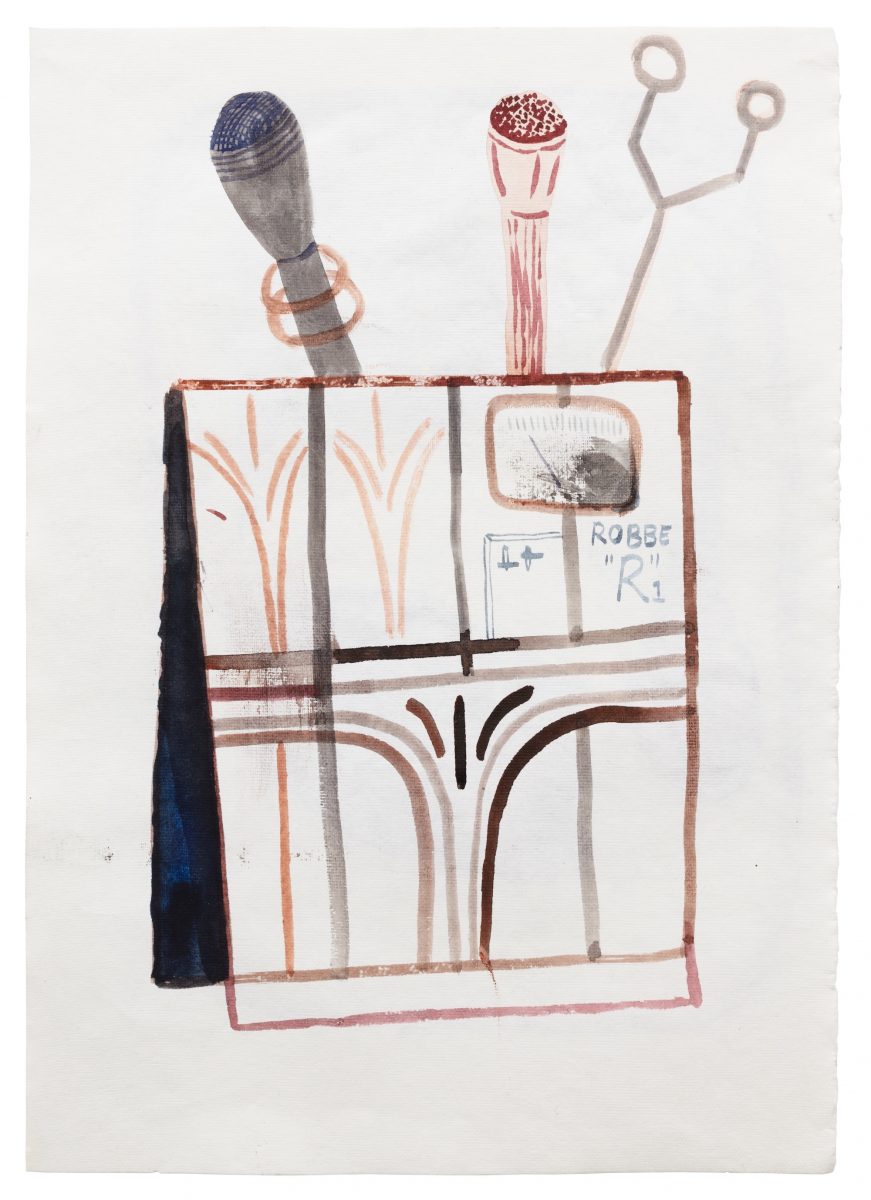

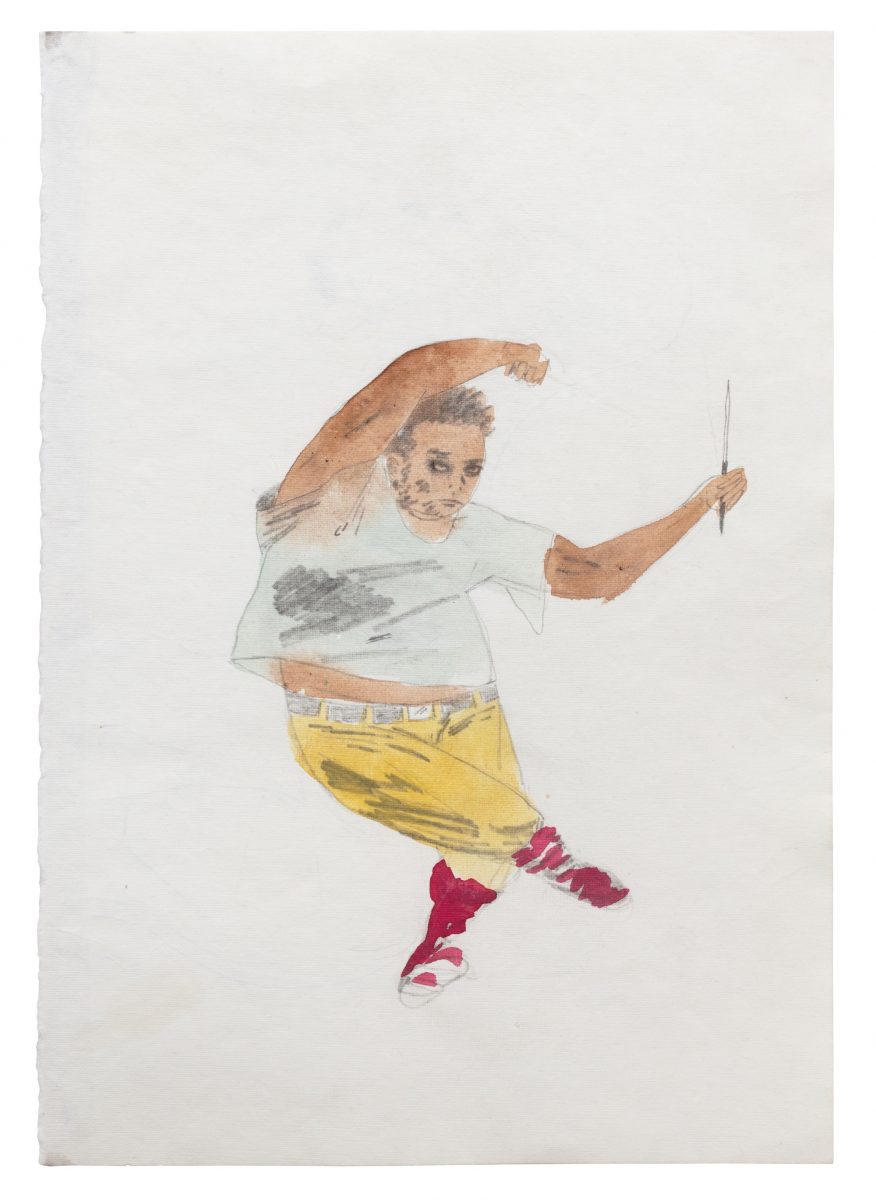

- Robber Radio, 2016-2020 (left); Knife Dancer, 2016-2020; Unexplainable Hazardous (Top) Time (Bottom), 2016-2020 (right)

“The small paintings feel more monumental, and the big paintings feel like they’re from a diary”

It’s not only New York coming through in your work, it’s the Dominican Republic too. Are you able to detail those influences?

Everything I think about gender and politics has an origin point in the Dominican Republic, especially [Rafael Trujillo’s] dictatorship that lasted from 1930 to 1961. The regime blacklisted my family at one point, so they couldn’t leave the country. Then when he was assassinated, my family could leave.

I lived there every summer from 1981 to, I think, 1997. I got sent to live with my grandmother and aunt so my parents could work and not have to worry about childcare. My mother’s side of the family are very poor: cleaners and home attendants. And my father’s side is a little better off: mechanics and military people. I had a very different life over there. It just felt like this magical realm which I got to enter in the summertime and, with the privilege of being somebody that’s born in New York, that carried a kind of status.

I got to see firsthand a certain kind of resourcefulness that I’m definitely adopting in my practice in terms of how I use materials. Back then I didn’t see it as art, I didn’t see it as people being creative: it was about people surviving. I’ve seen entire homes built from smashed tomato cans. And there’s a beauty there that I recognised early and carried through in terms of thinking, “This little chunk of paper that I found stranded on the street, there’s something beautiful there, what can I do with this?” It trained and conditioned my eye to understand that there’s potential in certain kinds of materialities and ways of using resources so that nothing is wasted.

Kenny Rivero: Palm Oil, Rum, Honey, Yellow Flowers

18 March – 13 June 2021 at Brattleboro Museum & Art Center

VISIT WEBSITE