Ludovic Nkoth’s paintings typically investigate the tensions, familiarities and people of the two countries that have so far defined his life. Born in Cameroon, the artist moved to the US aged 13, leaving his birth-family and siblings behind and settling in South Carolina. Now based in New York, Nkoth’s work encompasses vibrant group scenes and intimate headshots, ranging from children playing in the park to countless studies of his younger brothers (and he painted a portrait of his grandmother specially for 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London last year).

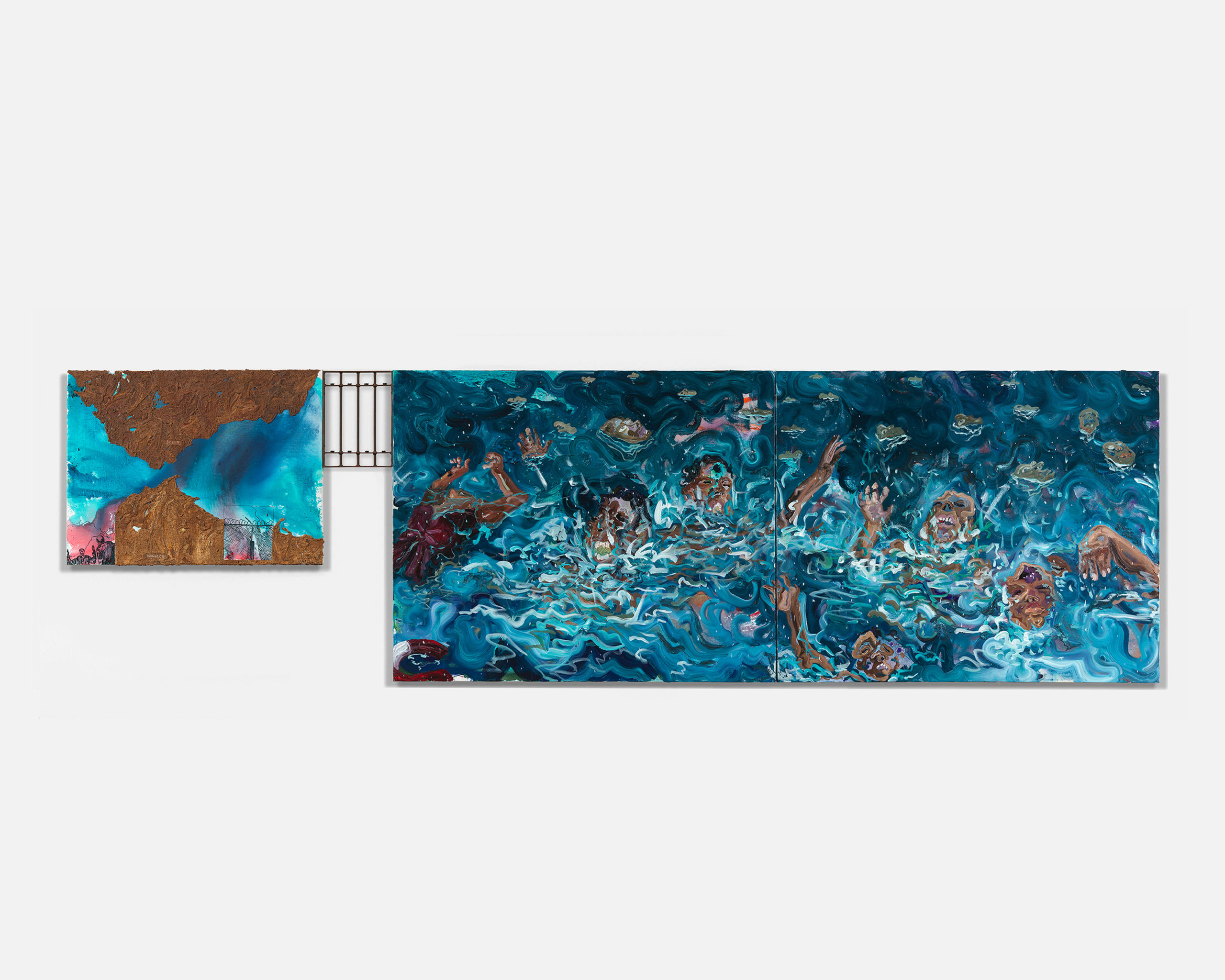

But hanging in Turin’s Luce Gallery, his sparsely arranged canvases instead focus on an in-between zone: a place that cannot be departed from, arrived at or assimilated into, but exists as a liminal site of distress and almost inevitable suffering. In You Sea Us, Nkoth explores the devastation of migrant crossings in the Mediterranean, attempting to reclaim the victims’ humanity while refusing to sanitise their plight.

“My idea was to travel to Europe and create these works on European land to show them everything they are refusing to face in their own backyard,” Nkoth writes of these latest works. The artist pays significant attention to the visceral nature of the sea to achieve this: its waves and currents, often invisible to the naked eye, are marked with an array of different blues to signal changing energies, while he continually blurs the boundary between body and water to capture its force.

“Waves and currents, often invisible to the naked eye, are marked with an array of different blues to signal changing energies”

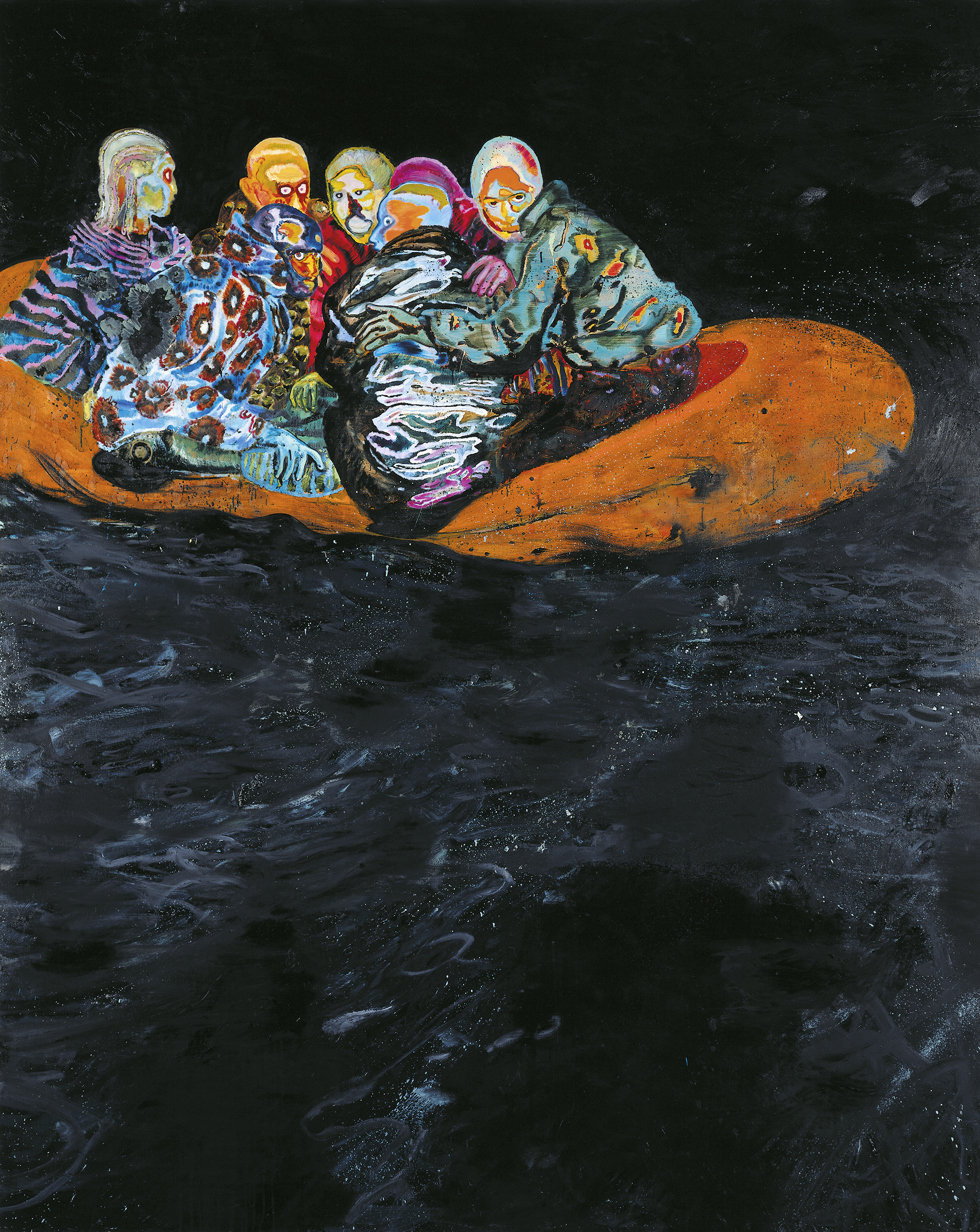

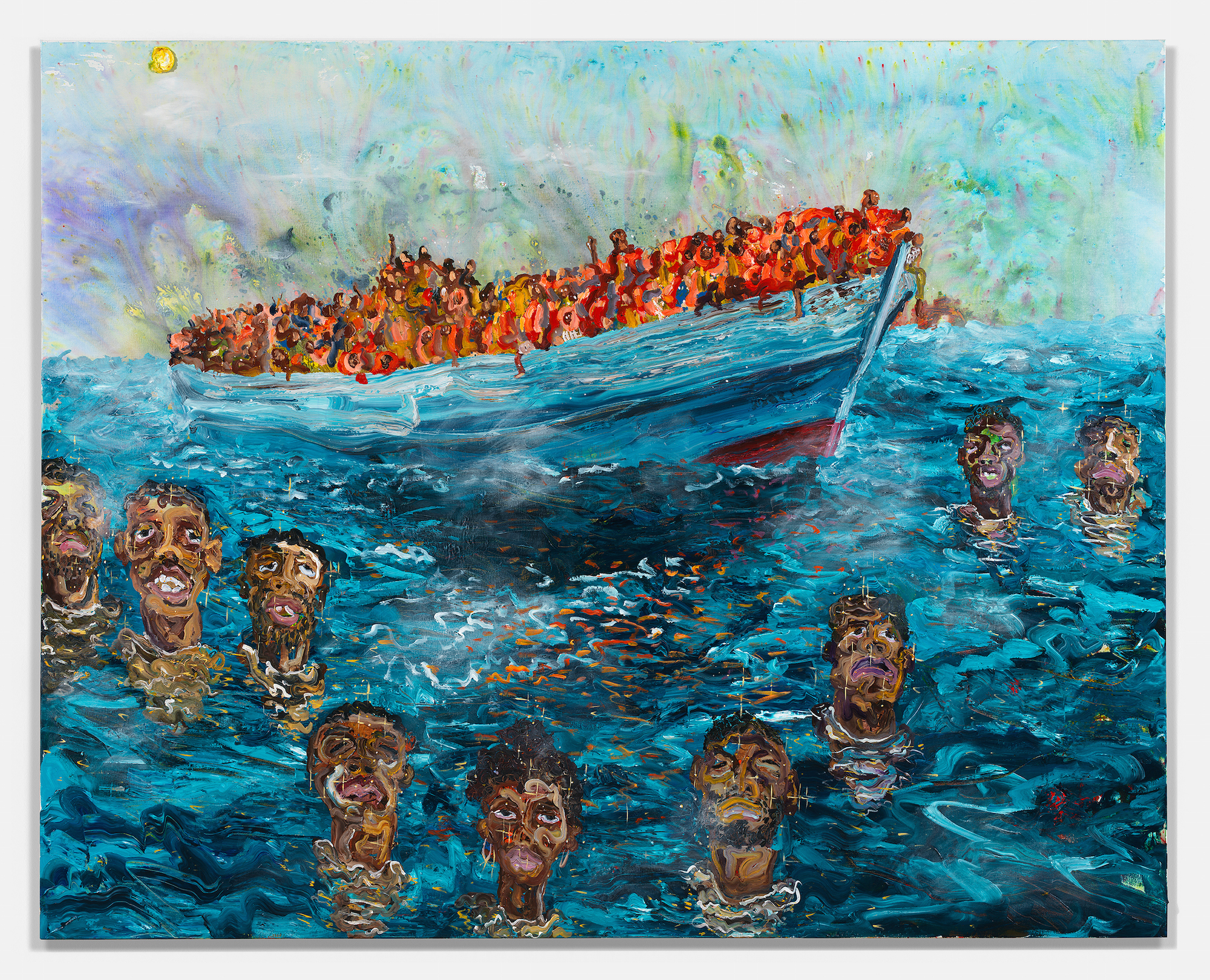

Lighthouse evokes Daniel Richter’s Tarifa (2001), for which the German painter’s inspiration was a news photograph from 2000 depicting African migrants stranded in the Mediterranean as they attempted to reach Tarifa, a Spanish municipality on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula. Nkoth’s own navigation of the relationship between Africa and Europe unifies the two works, which together draw attention to a continued tragedy at least two decades in the making. “I lived in Spain for a couple of months during the pandemic because I wanted to experience what it would even feel like to walk around that part of the world as a migrant of colour,” Nkoth writes of You Sea Us. The resulting paintings are heavy with the knowledge that not all are able to complete the journey safely.

Whereas Richter uses inky blues to create a threatening continuity between the sea and skyline, Nkoth’s heavy, mixed brushstrokes evoke the current’s intensity against the sky’s calm, pastel hue. And in doing so, Nkoth’s realises what the earlier work only anticipates: migrants fighting for their lives in the water, the fiery orange of their peers’ lifejackets ominously absent from their submerged bodies.

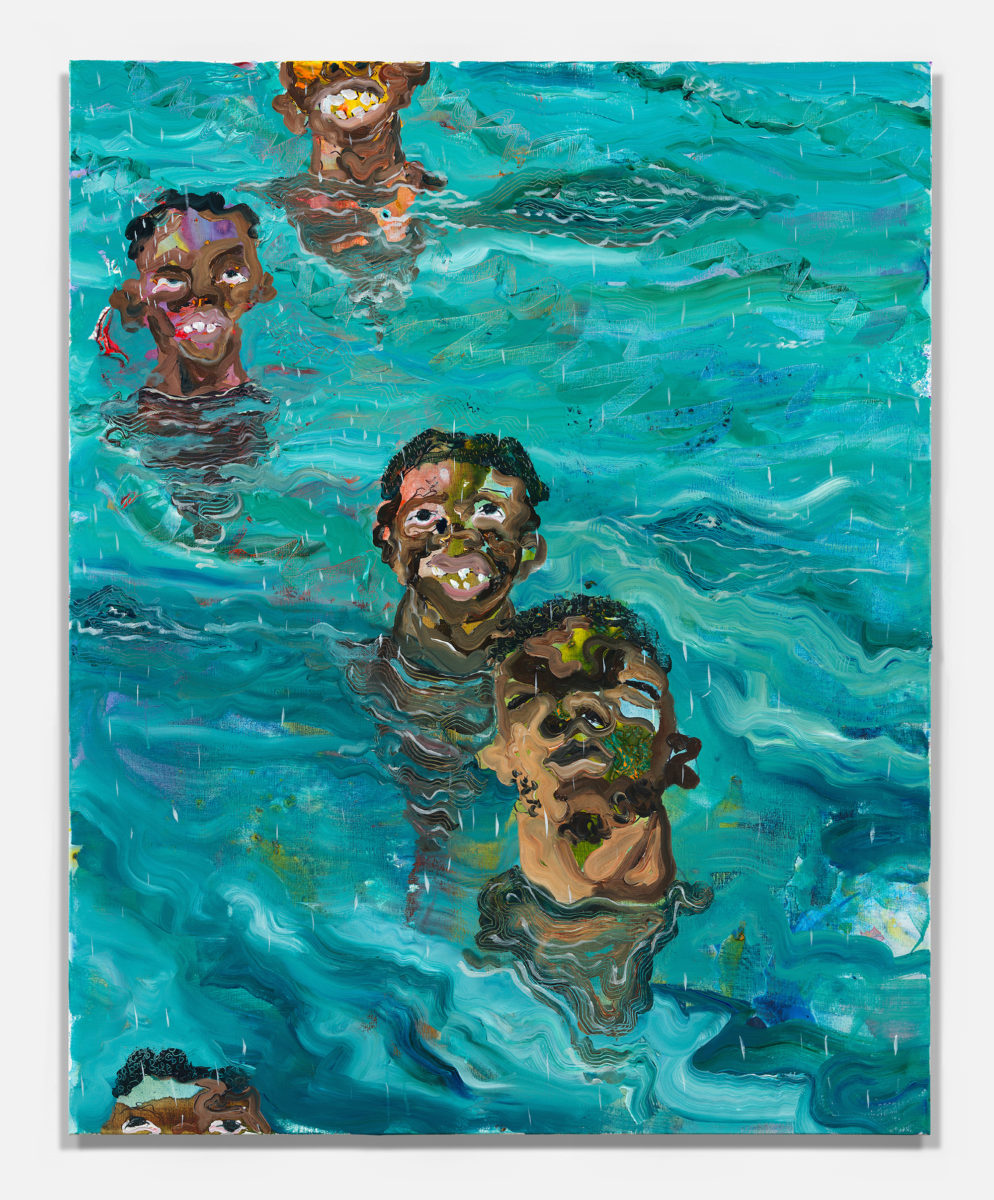

By treating such a visceral subject as a motif elsewhere in the exhibition, Nkoth creates space for a more considered aesthetic investigation of the human body in water. The Last Note appears as an extension—or perhaps, a detail study—of Lighthouse, the water here taking on a luminous turquoise while faces are rendered more abstractly, suggestive of an inevitable anguish, but also allowing for experimentations in pigment. To the upper left hand side of the canvas, a figure’s forehead gleams with iridescent purple, a hint of yellow forming an arrowhead above his eye. The Gates of No Return suggests a more obvious violence, the white brushstrokes overlaying the faces as bodies thrash in the water. In both of these paintings, the sky is nowhere to be seen.

“The paintings are heavy with the knowledge that not all are able to complete the journey safely”

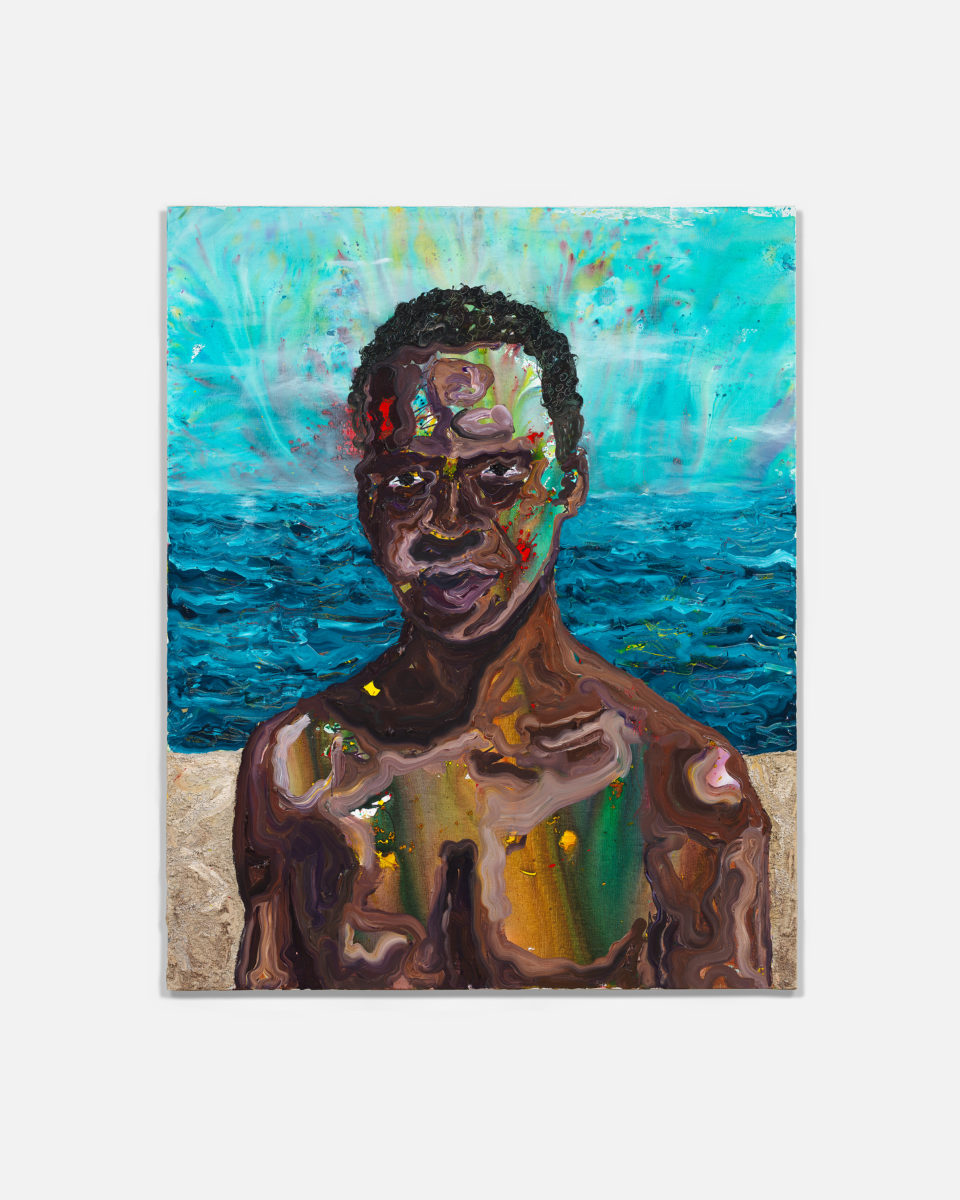

Do They Hold Me Down is a self-portrait with similar qualities, the shadow below the body “standing for all those souls lost in the Mediterranean,” according to the artist. Below the canvas hang threaded black and red coffee bean trivia shells, arranged like a series of necklaces. They reference a time when Cowry shells were used as currency across Africa and the world, while simultaneously representing the numerous people lost at sea while making migration crossings. Nkoth’s painted masks look beyond this series towards his wider practice, where the artist focuses on African imagery and belief systems. Sitting alongside the paintings here, the exhibition’s sculptural elements add a further human quality to Nkoth’s migration subjects, while individual studies of shells recast the sea as a life provider.

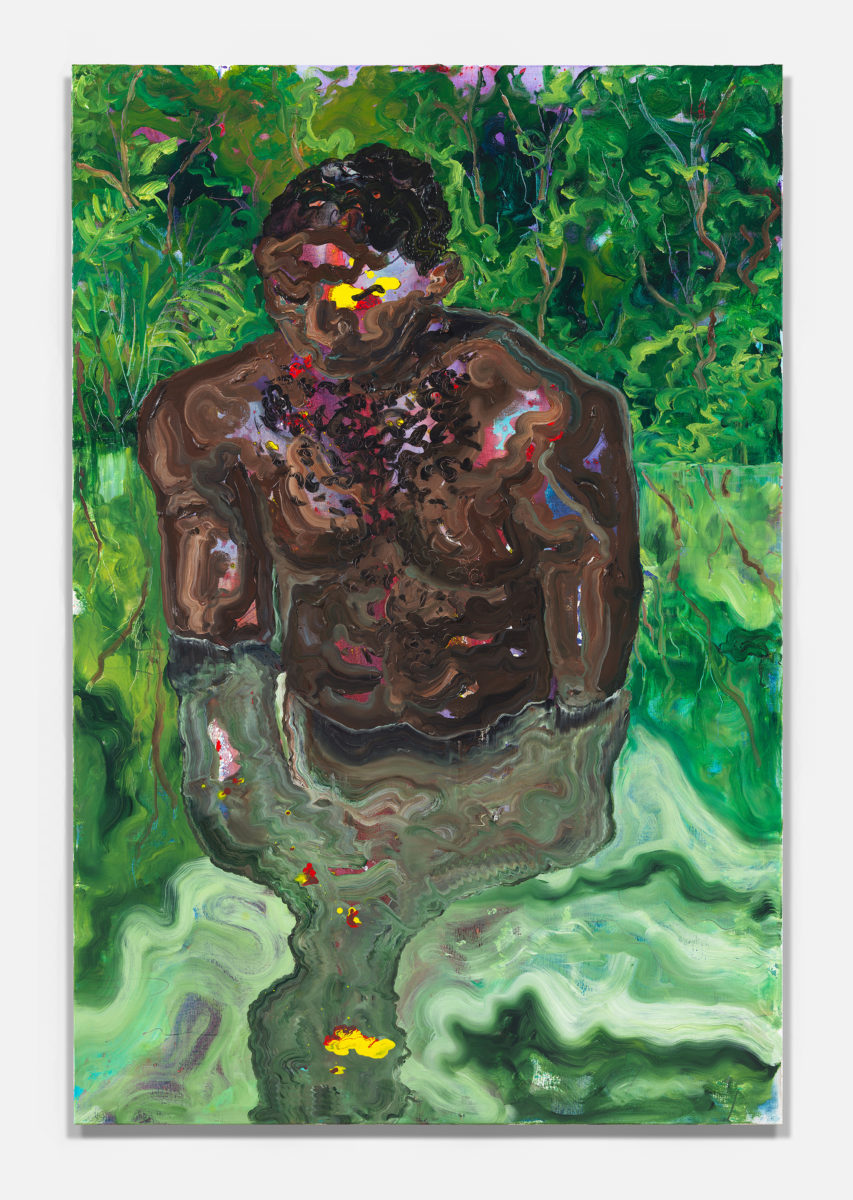

The Light In Me is perhaps the most hopeful piece: the figure is surrounded by lush green vegetation, though the blurring of the lower torso again suggests immersion in water. But on this occasion, Nkoth’s subject floats not in the unforgiving sea, but a still spring.