The You in Us—Lydia Ourahmane’s solo exhibition at Chisenhale Gallery—comprises installation, sculpture and sound, used collaboratively as a means to explore ideas of exchange and encounters. Much of the commission was developed while working from her family home in Oran, Algeria, and is focused within a wider context of migration, displacement and the nuances of politics and history. Ourahmane has also created Paradis, 11.10.2017, 23:45 (2018)—a silent, moving image online commission—which can be watched on the Chisenhale website, and thirteen hand-printed limited edition photographs.

The central core of the exhibition is Paradis (2018), composed of twelve transducer speakers and twelve amplifiers, embedded underneath a temporary wooden floor in the gallery. “I call it a sculpture,” Ourahmane clarifies. The hour-long soundscape is a combination of field recordings with wave sequences, composed and performed by the artist and others. Ourahmane, who studied violin and piano to grade 8, explains “This is the first work I’ve personally played instruments in. Along with the violin, the other instruments are saxophone and guitar. They’re used to give a spatial body to the clips, which come in and out, which were recorded on my phone or other devices.” While in the space, the score vibrates throughout my entire body, rising up through the floor, into my feet and radiating up and throughout my limbs. Transducer speakers are conventionally used in sound therapy, due to the ability of the vibrations to create a “trance-like” state of calm. The openness of the space invites you to lie down, to meet the sound and let it envelop you. “At the opening, everyone just sat on the floor. It was so relaxing,” Ourahmane says. “I want people to feel as part of the work as I do.” A lack of hierarchy, specifically within the experience of hearing music, was important. “Everyone can understand it on the same level, that’s why I work with sound. And even if you can’t hear it, you can feel the vibrations. Sound has a physical effect on you; the way it impacts your body. I’m often trying to escape the idea of the gallery, so I don’t see these works in relation to the specific space. It’s just where they happen to exist now, but they could exist anywhere.”

Ourahmane had initially thought she might make a film for her commission, but after spending more time in Oran, it started to feel inappropriate. “Images felt so wrong for that situation. The production of images around such sensitive topics is extremely violent. The camera felt like a foreign object. There was no way that object could exist in those interactions,” she explains, “I started filming on my phone instead, it felt less alien and forced. I was so aware of how fractured Algeria’s recent history is, and what that has done to the country, and to its people. How can I talk about that in current terms? How can I explain what that tension feels like there, right now? In images, you can’t feel those things.” The floor work functions as a record of a period of time, one marked by a change in Ourahmane’s feelings towards Algeria. “I had a very romantic idea of Algeria as home. I moved when I was ten, but we always went back and forth and spent summers there. When I started doing art and went to study at Goldsmiths, I felt this pull to work there. It’s where I felt inspired. It’s always existed in nostalgia, and in such romantic terms: the light, and the landscape,” she says. “This year was a real shift. I see the floor work as a record of events in which that shift happened, when I started to feel a different way about the place.”

Much of Ourahmane’s exhibition illuminates situations of war, violence and collective trauma, but the works are experienced in a subtle, physical mode, predominantly through a technique of cause and effect. The ethics of witnessing are framed as feeling, as being. The first work in the show is Doors (2018), two heavy silver doors treated black with sulphur. Throughout the duration of the show, as staff and visitors interact with them, the surface will slowly peel and become silver again. Finger and handprints have already started to blur together. “Lying down on the hard floor forces you to recognize your body, and to become more present. The doors are deliberately so heavy,” Ourahmane continues. “They act as a record of a period of time. I wanted everyone to have a part in making it turn back to silver. It records every single presence that has entered or left the space.”

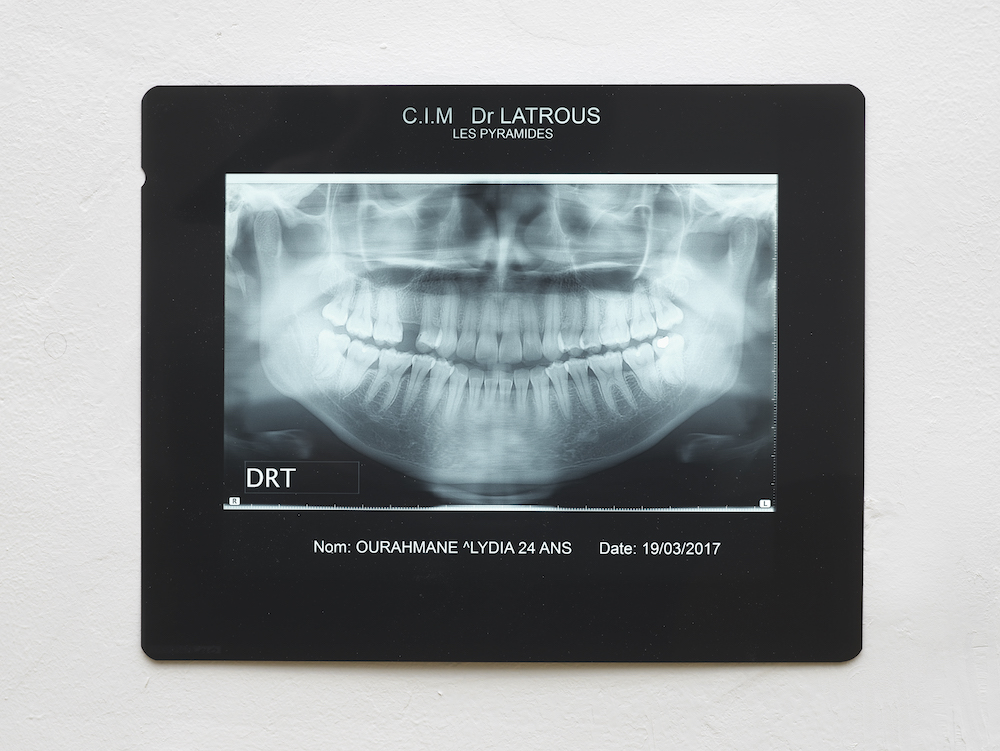

Another key part of the exhibition is In the Absence of Our Mothers (2015-18)—a single gold tooth installed in the space, and another installed in Ourahmane’s mouth. The gold was melted down from a chain she bought during the production of an earlier work. “Gold is an interesting material,” she explains. “If you bought it first hand, and then returned it, it would lose value instantly, just because it’s changed hands. That’s what I like about it.” Other documents—in addition to the x-ray scan of Ourahmane’s teeth—refer to Ourahmane’s grandfather, Tayeb Ourahmane, who extracted all his teeth in resistance to joining the military service under the French occupation of Algeria. His conscription cards and his 1954 French passport, which were brought to Ourahmane’s attention when her family began using them to claim French citizenship, are also on show.

The visceral engagement encouraged by the exhibition has roots in deep listening and non-linguistic practices, such as Pauline Oliveros’s “sonic meditations”, or the use of the Guembri instrument in Algerian Gnewa music. In the accompanying interview text with Chisenhale curator Ellen Grieg, Ourahmane discusses the significance of the Guembri which is “made out of the neck of a camel, one piece of wood [and] the strings are made out of the intestine of a goat. They talk about how the instrument is therefore made out of three souls, and the souls that are present in these materials bring you into a state of trance.” Ourahmane was specifically interested in how that object could resonate spiritual and emotional meaning, and embody past lives. “When my dad gave a talk about his father at the gallery last week, he ended it by talking about how he died one month after his mother did because he just couldn’t live without her,” Ourahmane expresses. “It was so beautiful. In the whole show, there are a lot of doubles. Two teeth—cut from the same chain. Two doors. Only two of the photographs are shown at front of house. It really references a relationship. There is no individual.” The exhibition’s four main parts, all grounded within the politics of both physical and mental space, intersect with the materiality of the subjective body. There is no you, there is just us.

All artwork commissioned and produced by Chisenhale Gallery, London. Photo: Andy Keate