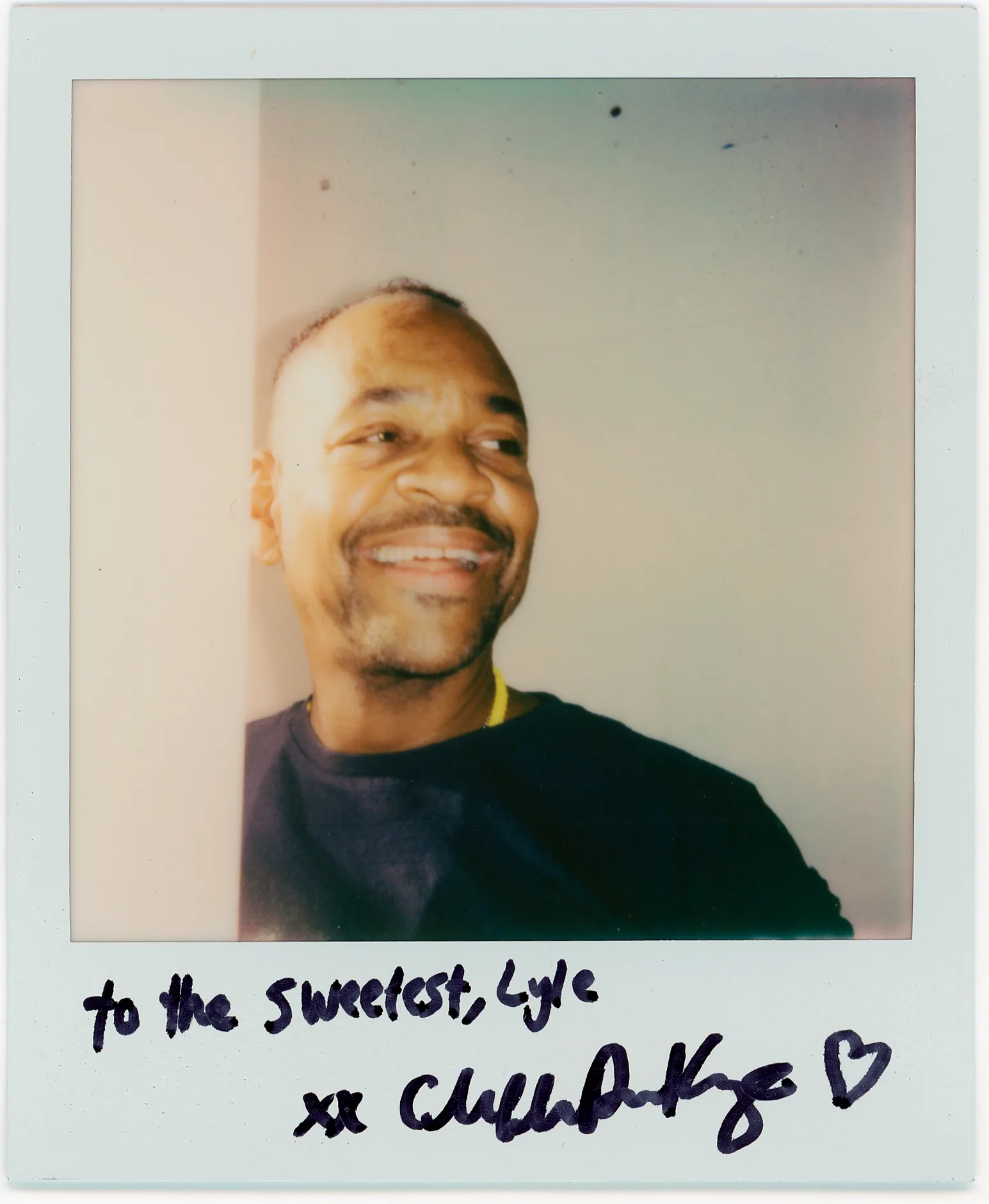

Following his recent exhibition at the Queens Museum and the publication of his latest art book, Shanekia McIntosh speaks with Lyle Ashton Harris about the unburdening power of photography, the memory and care embedded in his work, and the value of slowing down. Photographed by Clifford Prince King.

In ‘In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life’ from her book of essays Art On My Mind, bell hooks writes candidly about an image of her father that she held precious. It was the first time she saw him not merely as her father, but as a man with a life beyond the roles of father, husband, and worker. In her essays, hooks discusses the transformative power of Black photography, framing it as a tool of recovery and as a means of resisting dehumanisation, as it enables Black individuals to actively participate in the production of their own image. This essay, published three decades ago, easily serves as both a thesis and an apparatus for understanding the framework, artistry, and power of Lyle Ashton Harris.

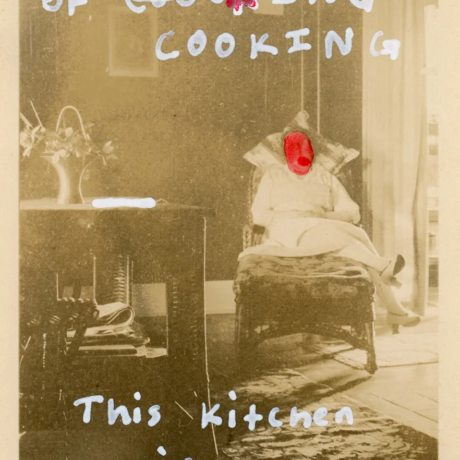

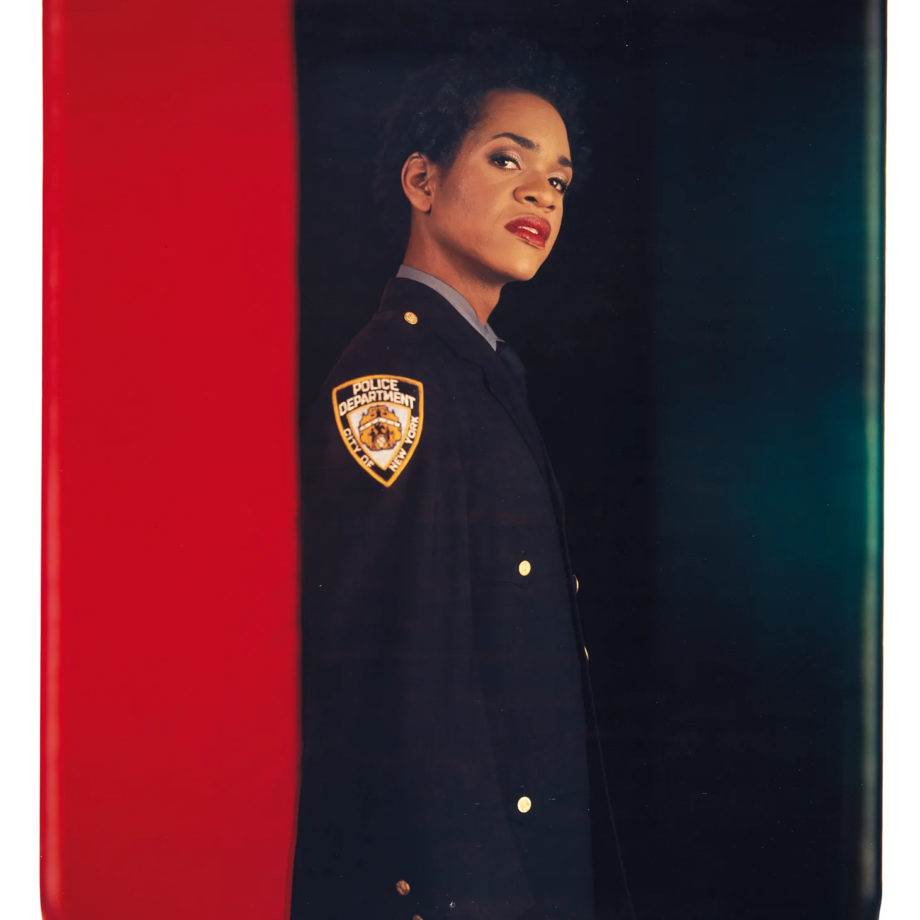

Lyle employs various modes of photography, ranging from research-driven studio pieces like Billie, Boxers, Better Days (2002) and Saint Michael Stewart (1994), to textiles inspired by his ongoing pilgrimages to Ghana since his teenage years, to documentary, as seen in his Ektachrome Archive. He arranges these works into assemblages and vitrines that allow us to traverse through his memories. Harris’s work conveys a sense of unburdening—unburdening and liberation from oppressive conventions, even as it documents attempts to escape them. His work also evokes a profound sense of personhood—not only his own, but also that of the subjects who represent his community, interests, and experiences, all seen through a Black diasporic lens.

This idea of personhood has been an ongoing journey for Lyle, dating back to when he first picked up a camera. One of his early works, I Long For The Relationship We Used To Have, opens his new art book, Lyle Ashton Harris: Our first and last love, produced for his survey show of the same name at the Queens Museum. In Playing the Game, originally created as his graduate school thesis, Lyle wittily eviscerates the concept of ‘the game.’ Reflecting on the work, he says: ‘It is important to acknowledge that many people did not make it. There were walls erected through language and, let’s say, othering people—not everyone had the wherewithal to deal with that kind of hazing. I think the piece talks about it. What I’m saying is that I absolutely abhorred the hazing.’

This revelation isn’t shocking to me; it has long been known that Lyle has been both an advocate and a much-needed mentor to younger Black artists. He embodies a sense of care and community that is evident in his practice and extends into the real world. A friend once told me that while many seasoned artists seem disinterested in engaging, even when it contradicts their practice, ‘Lyle is for real. He really does care.’ Even they seemed shocked and confused by his availability.

I was already nervous and eager about speaking with Lyle, a feeling intensified by the presidential election taking place on the same day our interview was scheduled. We spoke over Zoom while Lyle casually walked his dog through a park near his home in the Hudson Valley, a place that has served as his base since the pandemic. This move seems to have helped him articulate his archive through written language, a process that culminates in the highlight of his new book: the appendix on his Shadow Work series, which takes centre stage in the survey. Thoughtful, witty, and matter-of-fact, Lyle recounts his memories in these works, presenting a glimpse of his interiority to the reader. Through this body of work, we gain a clearer understanding of who Lyle Ashton Harris is and the experiences that have shaped both him and his art.

The appendix is dizzying; I found myself pouring over his various anecdotes for days. The charming recollections of the histories behind objects—some collected from other shows, ephemera, and photos—read like a raucous memoir, offering insight into his artistic process. These images carry weight; their visual impact is undeniable, but it’s the recollections and stories Lyle reveals that add another layer of depth. ‘What initiated the idea of the appendix for me was very much based on the experience of the pandemic,’ Lyle shares. ‘During the early years and months of the pandemic, my writing teacher, Laura Davis, was brilliant. Her capacity to create a safe space for people to delve deep and respond to prompts was invaluable. I took it very seriously—it was probably the first class I ever took seriously. I would turn my phone off during that period, and it gave me a different perspective on several things. The idea of really not turning the phone back on and slowing things down, that’s where the appendix came from. It emerged from those exercises of going deep, slowing it down, and being aware of what was happening.’

Simultaneously, Lyle was going through his archive: ‘Files, photographs, postcards, letters—correspondence to me, correspondence to others. A lot of these elements were in the vitrines at the museum.’ I was so engrossed in learning the context of his maps that I found it hard to think of what to ask him; he had already answered so much.

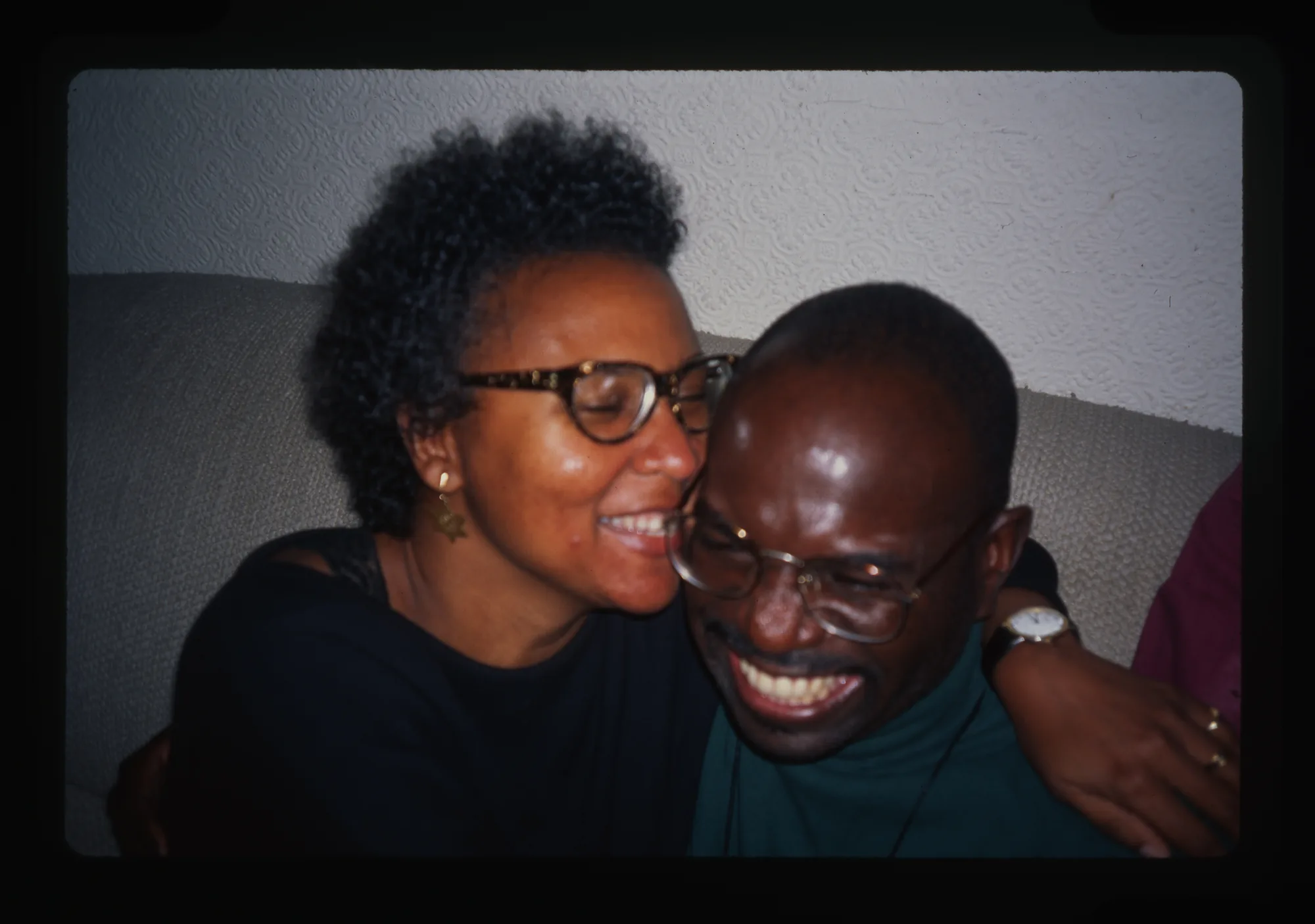

This past autumn, I visited Hudson Hall, the oldest surviving theatre in upstate New York, for the opening of a large group show. The exhibition featured work from local artists—large, boldly colourful paintings and sculptures. People busied themselves drinking, chatting, and admiring the work. I moved nervously through the crowd, slightly distracted by the small talk and congratulations. Then something caught my attention in the corner of my eye: Lyle’s portrait of bell hooks and Marlon Riggs together on a couch in the early 1990s. I recognised them both, but was struck by how casual the moment felt. Despite the mythology and academia surrounding their lives, here they were—real, grounded. They were people.

The portrait felt like a missing puzzle piece, and I immediately recalled a similar feeling from Lyle’s survey show opening. To Lyle, this observation made sense: ‘It conveys a deep intimacy that we often don’t see in public life, especially with Black subjectivity,’ he explains. ‘Communal intimacy is fundamental to us as Black people, Black citizens on both sides of the Atlantic. That photograph, in particular, captures not just a behind-the-scenes moment, but lays bare the fragility around intimacy—cross-gender, cross-sexuality.’

In the coming years, the question of what it means to protect oneself—of hiding in fear of danger—will likely become more pressing. There is no rulebook, but perhaps it’s worth reflecting on ourselves and our history. Our lineage. That photograph carries strength; it shows we can remain steadfast in our practices and critiques while still asserting our personhood—a balancing act that is both loud and incredibly difficult, with the work never-ending. ‘I think that photograph you experienced is imbued with the knowingness that this is where the real work lies,’ Lyle says.

I take a deep, shaky breath. There are so many things left to think about and ask, but our time is up; Lyle is back in his car, ready for his next move. I shuffle my papers and quickly ask about his plans for the rest of the day. Nervous about the election results, I hold my breath. Lyle, matter-of-factly, replies, ‘Well, I’m going to move some wood and have some lentil soup.’ I then ask why he dropped ‘Self Love’ from the book’s title, and he simply says it was implied. True. For the last few minutes, we exchange chicken recipes.

Written by Shanekia McIntosh