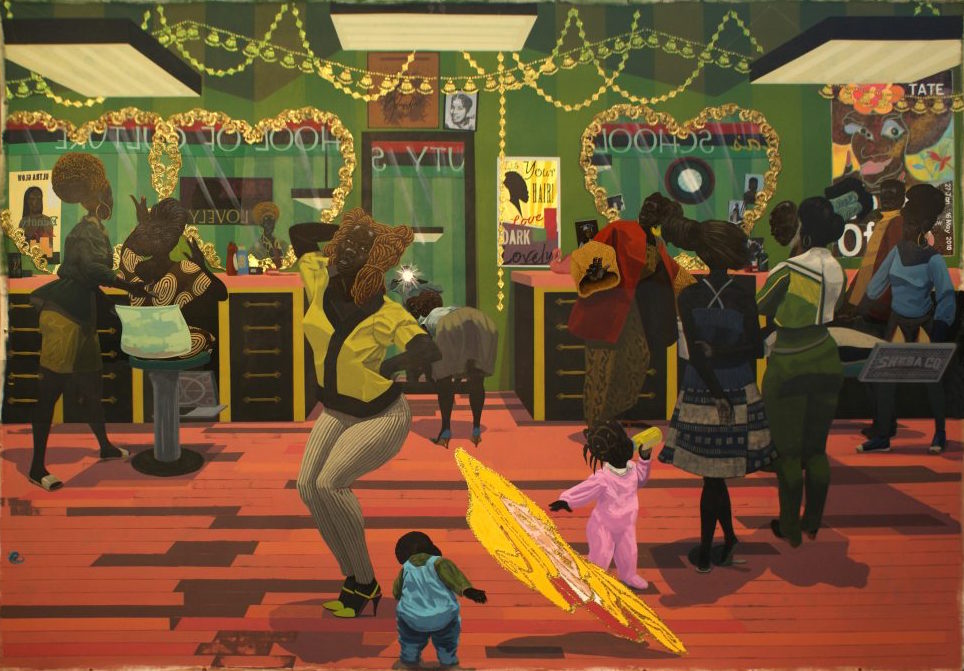

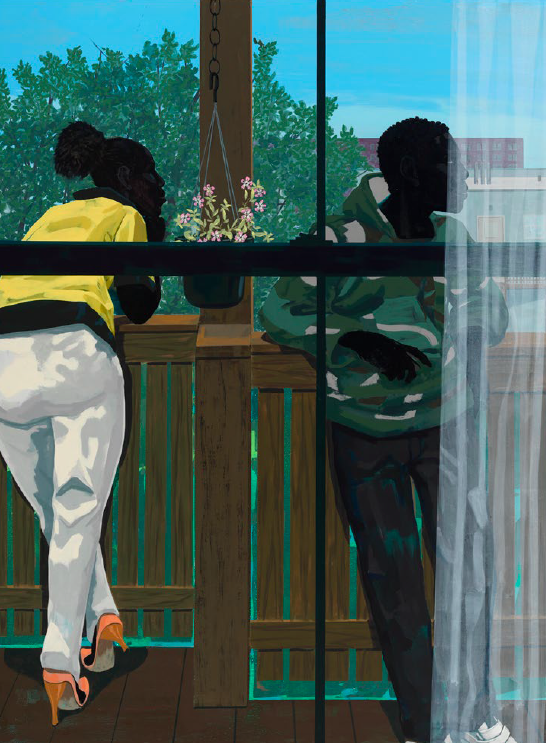

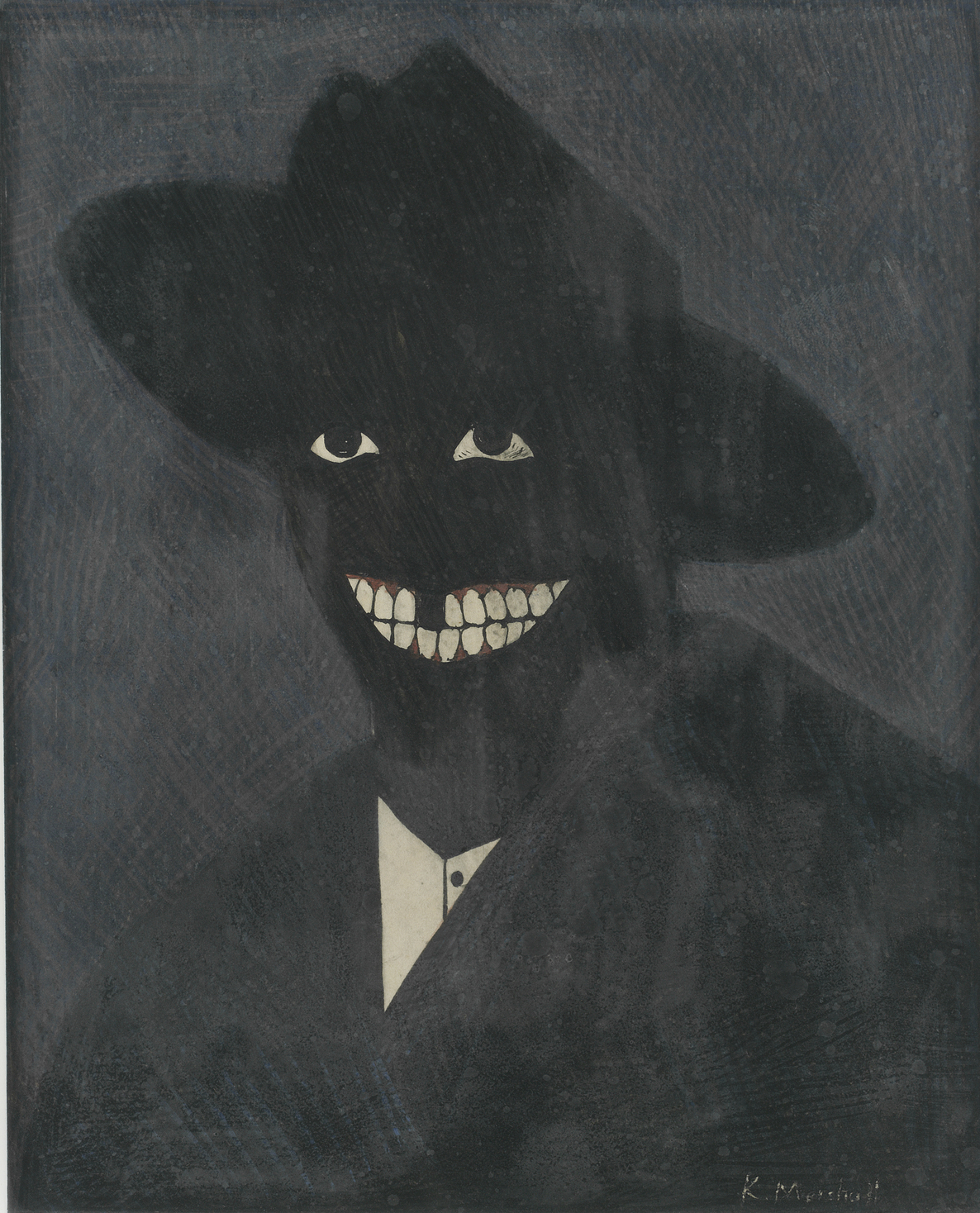

This winter the Metropolitan Museum in New York is hosting Mastry, a retrospective of the work of Kerry James Marshall. Since entering the art scene in the 1970s, Marshall has been a critical chronicler of the African-American experience, making large-scale narrative paintings featuring black figures, in a medium in which African Americans have long been invisible. Jurriaan Benschop visited the artist in his studio in Chicago.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 29.

Do you ever feel, as a figurative painter, that everything is already occupied in terms of painting?

Well, that’s the kind of thing you have to wrestle with: if there is space to create a new image. If you think there isn’t, then you recycle images that are already in the image base. For me, there is a necessity to find out whether there is still some small space where something new might be introduced. You cannot accept that just from the critical dialogue, just because people are telling you. You’ve got to find out yourself. All this is about finding out whether you can make new images. Most of this is determined when you arrive at a certain amount of mature consciousness. I came out of school in Los Angeles in the late 1970s, when practically everything was supposed to be exhausted. It looked like there was no room for you to do anything except follow leads that somebody else had established. For a black person making art, that space for creating was even smaller because there was no real infrastructure that supported your ability to go outside the market. There didn’t seem to be that kind of space. It had everything to do with the way you were introduced to the history of art. What I learned is the history of modernism as an extension of what comes from Greece and Rome. For black people, there was no way in there. That confronted me immediately with the realization that I was outside the capacity to generate new things in this domain, because the narrative was already claimed. When artists in Europe started appropriating African art and Oceanic art, they used that as raw material in a formal sense. They would not talk to anybody who made that stuff. There was not a history outline, not a theory of form. So we were outside the intellectual tradition.

Did you have a circle of people back then discussing these kind of topics?

It’s the kind of conversation that circulates among black people all the time: How do you get from the margins to the centre? It still is that way.

But now you are in the centre. You are a successful artist, showing in top museums.

No. It depends how you define it. In the market maybe. But in the critical conversation, the question still is: Who is in it? Who is the black equivalent to Rosalind Krauss, or Benjamin Buchloh, or to Hal Foster…? Who speaks with the same authority, who is engaged in really shaping the general understanding of what is radical or is advanced?

Okwui Enwezor does…

Yes, but he is brand new. He is successful in moving African artists into the general discourse of art. But he is singular.

[Some recent paintings by Marshall are called Blots. They look like Rorschach tests, with their symmetrical and apparently accidental configuration. I was surprised to see these seemingly abstract works—for the first time during the 2015 Venice Biennale—alongside figurative paintings. But abstraction, Marshall indicates, might not be the correct word here…]

Rorschach images are vehicles for free association. As a phenomenon, it is a thing that happens, as opposed to images being constructed from predetermined sets of shapes. It’s a random phenomenon, not a composition. The Blot paintings that I made, though, are compositions. It’s actually three blots stacked on top of each other and then further multiplied, and then when I make the painting I use that as a point of departure and build an image that looks like a thing that would have been derived from a Rorschach. So actually it is a representation. It’s a figure. And that was part of what I meant, to have a conversation about what abstraction is.

If you follow your work over the years, it seems like you can paint in very different modes: figurative, abstract… Did you move into the space where you want to be?

My Blot paintings have a lot to do with this conversation. On the one hand, there was always this sense that you could not get to the centre unless you abandoned the black figure. To me, that is a problem—if I have to abandon that figure in order to get to the centre. So I insist on bringing this with me. The challenge is to figure out a way to make this work. To make it operate on the terms I’m trying to set, instead of surrendering to a way of treating the figure that seems superficially mainstream.

Are your figure paintings pure inventions, or do you partly work from observation?

When I do a painting there is no prior image that exists, except for some drawing. My paintings are not based on observation; they are an idea of something. The details that I select for the picture have to do with how they add to, or enhance, or refuse a kind of narrative. It’s about if I want the image more or less narrative, or more or less inert. While painting, I’m making decisions all the way through about the relationships between shapes, about the symmetry that you allow. In figure paintings there is a given structure to the representation, the body in space. I try to be precise about the way the space is organized, especially if there is perspective. After that reality is established, you can improvise within the two-dimensional structure of the picture.

It seems that you are very much interested in what the Western tradition has produced in painting, and that your work develops as a dialogue with tradition.

I didn’t have a choice.

Or maybe you just liked it?

Well, it is both. I didn’t have a choice and I like it. When I was first introduced to art it looked a certain way. It was Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael. Before I had a chance to look at anything else, that is what I was given. The history was built around that. All of the books in the library were about that.

Did that annoy you?

No, it didn’t annoy me because I didn’t know any better.

Could you identify with the paintings you saw in the books?

They were cool paintings, they looked amazing.

For a viewer, it seems essential that he or she can identify with what is going on in the paintings.

They were biblical stories, or mythological stories, or naked women and so on. When I first started seeing things, it formed my whole orientation of what is beautiful, what is powerful, or attractive. I couldn’t look at those things and say: Well, that’s not good. It was just there and it looked good. People said it is the best that could ever be done. But then at some point you have a crisis of consciousness. Then you have to make a decision on whether you identify with one thing or another. Once you discover there is an imbalance of power in determining how things are valued, you have to decide: Which way am I going to go? It happened early for me, through the encounter with an artist named Charles Wilbert White. Why didn’t I see his paintings in these books? It looked as powerful as anybody else’s stuff. But nobody was talking about it. This was critical to me. Why is there this discrepancy between what I think I see and what people claim to be the most important?

So there is a political view. But how can that be involved in artworks?

In part it is political, how things got established as paradigms. There is no universal agreement on what is the best. This was all determined in power struggles between different factions. Is the artist simply passive, a tool for one political, economic and social camp, or another? Do we have anything to say about where we fit in and what our chances are of being part of the authority deciding modes of appreciation? Must I just wait to be “discovered”, or do I have anything to say about my terms of success? Those are important questions and I have to be able to decide. I cannot leave it to somebody else to decide whether I can participate or not.

But that is kind of abstract: the mechanism of appreciation. There is no president of the arts who decides what is good and what is not…

There are thought leaders, though. And if you want something, you have to insist on it.

So one thing is to make the actual work. The other thing is… your allies, the ones you talk to and who support you?

It’s whether or not you can make the work, make the art, have some kind of effect in the world. I have to keep calibrating the work so that it produces the effect I want.

So for you it is a very political stance?

It has to be, otherwise you remain at the mercy of forces not aligned with your self-interest.

But maybe art is not the place to change the world…

Not changing the world per se. Take these black figures, for instance: the fact that museums have acquired some of these, to me, has effected a radical change. This has created the circumstance that people going into that museum won’t just see what they have always seen. That is a big change. The total absence of a black figure as the subject of a painting is no longer a given.

Your mission is accomplished?

In that sense, yes. For instance, the Ludwig Museum bought a work, that is a big deal to me. The mere fact that the picture is on view has already transformed people’s expectations there. That is a major achievement.

It still keeps you going?

Yes. The goal is to achieve critical mass of this kind of picture. What I want is to normalize the presence of that image. To do so, you need a lot. You also need other people committed to representing the black figure, and not just in painting. I use lots of strategies to make art. I have to know the strengths and weaknesses of one mode or another when choosing which one best suits my idea. If I make work that appears to be abstract, I’m making that for a reason too. A number of black artists shifted away from figurative to abstract work because they felt it limited their access to the mainstream. They wanted to be free of the perceived limited readings imposed on their art because they were black. For me, that is a kind of failure—a surrender to white supremacy. If you really want to be free, you have to be free in the fullest sense of the word. That means not being ashamed, not feeling diminished by a racial identity, able to project an ideal image like yours powerfully into the art world. That is the crux of everything. Gerhard Richter moves through a variety of modalities, images, abstraction, installation and other things. He is not worried that making a picture of his child weakens him because he might be identified as a white, German man. I am not afraid to be identified with the black people that are in my pictures. That does not scare me.

First you have to work figurative, in order to work abstract?

If you look at the history of art making, you can ask: What compelled the changes in style and philosophy that the narrative tracks? Why did artists move away from figures into abstraction? There was a necessity to differentiate oneself from an overpopulated field of competitors schooled in the academic mode favoured by patrons of the time. Abstract picture making is, likewise, the academic mode favoured by late twentieth-century patrons, and is an equally oversaturated arena. The fundamental principle of art making is representation. I believe one should stay with representation until something happens inside the pictures you make that compels you to do otherwise. There are quite enough problems to solve to keep you going for some time. If you never succeed there, and you go to abstraction because it seems easier, you miss the philosophical and aesthetic questions involved. Besides, how many more abstract pictures do we need to see in the world, really?

What are the specific possibilities that painting has to offer to represent a figure?

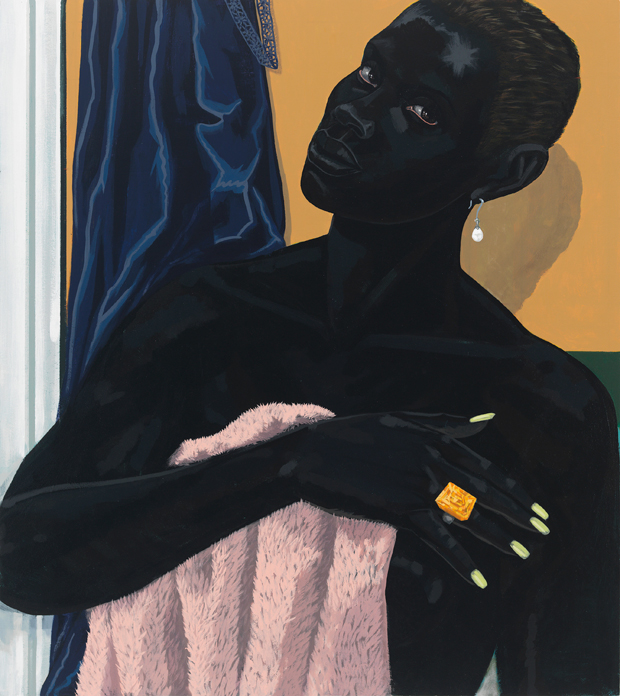

It can show people something that they would not be able to see otherwise. Not in a photograph, not in the street. You would not be able to see the combination of things, unless you see it in the picture. It is not reality, it is the picture reality. You also have to note there are a lot of things I am not doing. The figures are not decorative, they are not ornamental. They are also not abject. I’m not trying to dissolve the authority of the image. I’m not working that down.

Is it about psychology?

It is about presence. I try to make sure that the figures in the painting have their own independent psychology that is not dependent on the psychology of the spectator. They are completely self-absorbed in a lot of the paintings. My pictures are always about being a picture too. Take the wedding portrait of Harriet and John Tubman. Harriet was considered to be one of the greatest conductors of the Underground Railroad. She helped people get out of slavery in America to Canada. She was called General Moses, a nickname. She was a tough woman. She was married for a short time to a man named John. My painting is a wedding portrait of them. But there is not such a wedding portrait. So I make pictures that fill this kind of historical gap. Harriet Tubman is not typically represented displaying any kind of femininity, she is denied her femininity. I wanted to give that back, in a historical portrait.

There is a lot of black in your paintings. Some painters, like Luc Tuymans, don’t like to paint with pure black. How about you?

I reserve black in my paintings only for the figure. Everything else is chromatic; it’s made with mixed colours. In most cases there is no black or white. You can make a colour that functions as a black in a picture. It may be a deep violet or green that behaves like black. In this case, you are playing with colour temperature. But in the figure, there is pure black. They are essentially black.

You think that white people will always see black people as different, and vice versa?

Yes, but that is ok. That difference is really not the problem. Power is the problem. There is a power differential between the West and just about everybody else. The people on the bottom perceive their difference as problematic. If there was a market structure, and an institutional structure in Africa that was an equivalent of the big national museums in Europe, if there was a tradition of artists in those cultures challenging traditions and assumptions, then they would not be as desperate as they are now to be part of the Western scene.

“Kerry James Marshall: Mastry” continues at the Met Breuer until 29 January.