Gyamfi began by exploring himself through self-portraiture, but his project has gradually broadened to investigate the various ways queerness and otherness are perceived in different communities in Ghana, where he lives and works. Rather than applying a Western ideal of equality, Gyamfi’s black-and-white photographs suggest a pre-colonial history of his homeland, when the lines of identity were blurred, and what you could be was more fluid and open.

Your most recent solo exhibition, See Me, See You, was at the Nubuke Foundation in Accra. Can you tell me more about the exhibition? How was the response?

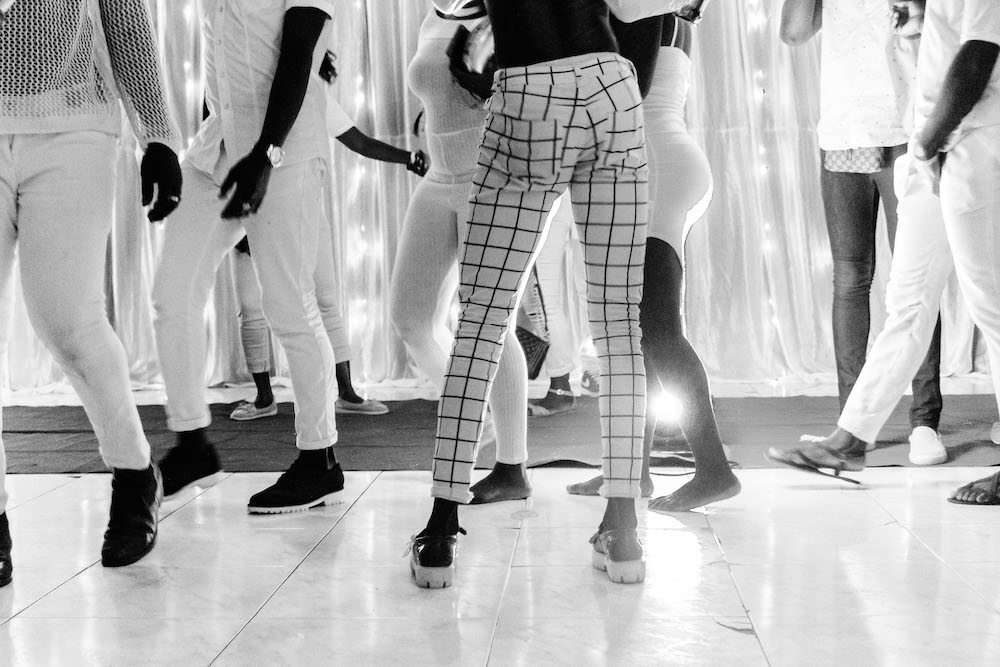

It was work that was really close to me and, after almost a year of making the images, we spent some months putting together the exhibition experience with some audience-participation features to help instigate conversations around our ways of perceiving the “other”, using sexuality within the Ghanaian space as catalyst. The responses were as diverse and complex as our humanity itself, but the most important part, for me, was the fact that people were willing to engage in a dialogue where they otherwise wouldn’t. For me that is an important first step.

You’ve said that you are interested in the ways photography can be used to interrogate social systems. When did you first realize photography could be an effective tool?

Art imitates life and otherwise. We have come to understand how active the process of making and creating our history as a people is. It is not a passive activity. Many forces and elements come together to make this happen, and photography as a tool for visual representation makes the photographic artist an important participant in the forging of said histories. But this doesn’t just happen, it goes through an evolutionary process, and it is in the process that I feel photography can intervene by positioning itself as an introspective tool through which questioning and evaluation can lend themselves to the reshaping of histories. Zanele Muholi’s work is an example of how such interventions can shape the bigger story/history.

Definitely—Muholi’s work as you say has literally given a face to a community that had otherwise been invisible in South Africa, and now that community is recognized around the world. Your earliest experiment with this idea was Asylum, I believe, in which you look at sexual identity in Ghana.

From the point of view of a young Ghanaian man growing up with an “alternative” sexuality, there is a certain level of confusion and paranoia. The absence of a local reference point from which to start finding answers to questions one may have can have some dire consequences, both psychologically and otherwise, and it was some of these tensions and confusions that I sought to articulate using self-portraits.

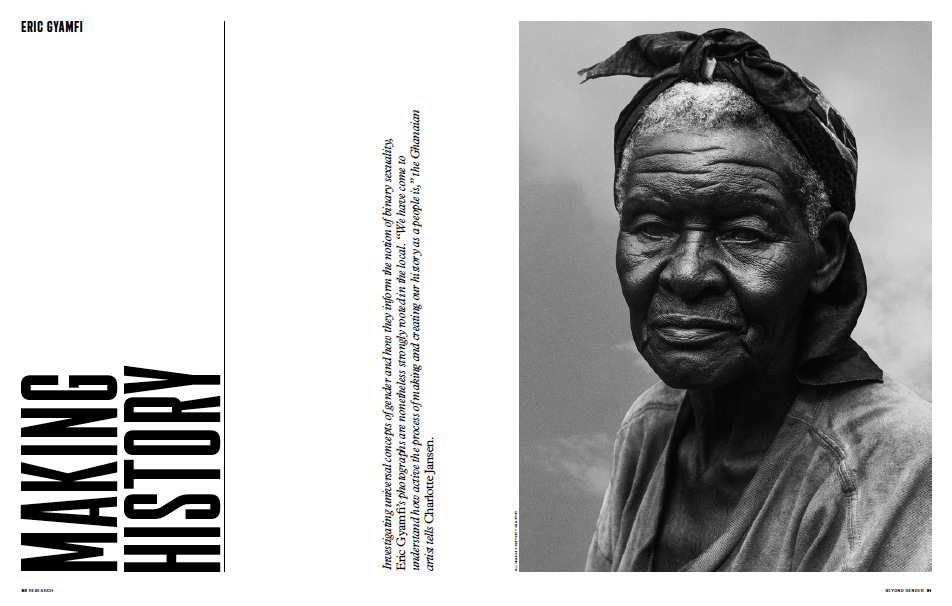

I was also very struck by the Witches of Gambaga images, portraits of women you took at the infamous “witches camp” in the East Mamprusi District inhabited by 130 women aged between seventeen and ninety. How did you gain access to that community?

When tensions arise between groups of people, it becomes quite easy to forget our shared humanity and the universality of some life experiences. That all people feel and are subject to joy, dejection and trauma. It is also in our nature as people to seek affinity with people we deem to be like ourselves and consequently create a wall with people outside of these groups. But thank God for intersections. It is an understanding that people are human first, and that sexuality, gender and ethnicity don’t change them as much as culture and social grooming do. My point of action then was to draw attention to this shared commonality.

“The actions of queer internationalism only go to engender the belief that LGBTI activism, just like homosexuality, is a Western import.”

As you say, there is this tension between tradition and modernization that you experience in Ghana, and you very much bring that out in your work. What do you feel about this present time in your country, in terms of attitudes towards gender and sexuality?

What I really meant was tradition as a fixed past, whereas tradition in actuality isn’t fixed and can be added to or otherwise. I feel the internationalism of sexuality and gender may have lot to do with this. I will quote a few things from Kenne Mwikya’s “The Media, the Tabloid and the Uganda Homophobia Spectacle”, where she posits at one point that Western paradigms of activism with regards to gender and sexuality may not necessarily be feasible or applicable in totality, and advocates for more localized and critical ways of dealing with the subject. I’ll quote a few lines: “but tensions between the aspirations of the West and the needs of places such as Africa and the Middle East cannot be blanketed by internationalism. Their paths are markedly different, as are the immediate needs that befall countries such as Kenya and Uganda as opposed to the US and Britain… The actions of queer internationalism only go to engender the belief that LGBTI activism, just like homosexuality, is a Western import, and an imposition on a people’s sovereignty.” Attitudes towards gender and sexuality are not the most progressive here, and there is a lot of room for improvement. Gender can become that intersectional ground upon which women and queer people can seek equality.

How difficult is it to speak about sexuality, and homosexuality, in Ghana? Male homosexuality has been illegal since 1860 and can be punished with three years in prison, while the laws on female homosexuality remain ambiguous.

Well, these laws are first of all one of the remnants of British colonial rule. Sexuality is not openly spoken about for the most part, regardless of whether it is about heterosexuality or homosexuality. (Granted there is more taboo surrounding open conversation about homosexuality/queerness apart from those instances where it fits into the church’s and politicians’ rhetoric of equating queerness to perversion and the eventual annihilation of the human race as result.)

But there was an aspect of our culture in times past as I have read and heard (maybe still is in certain parts) that allowed for a level of social inclusion of people of diverse sexualities, and didn’t even deem it necessary to name these ways of being. Certain ambiguities and contradictions were also allowed to be without the necessity of separating or labelling them. And it is these ways of inclusion that I want to draw our consciousness to.

Buy