“Boys Keep Swinging”, “Boys Don’t Cry”, “Jealous Guy”, “I’m a Man, You Think You’re a Man”… music has always sent us mixed messages about masculinity. Such conflict is what keeps the blood pumping. Because the most vital pop culture feels fruitful and fluid, its superstars chew up and spit out masculine “norms” with relish: David Bowie, Michael Jackson, Prince, the butch/camp flourishes of Freddie Mercury, the rugged intellect of Bruce Springsteen. All but one of those icons has left us, yet their collective influence endures.

When I was a little girl in British suburbia, I knew that white men held prime-time power, but my musical heroes were the fiercely cool women who seized attention in that male-centric world: Debbie Harry shimmering from our monochrome TV; Donna Summer astride electro-disco rhythms. Dynamic images and pulse-racing melodies.

Masculine “norms” also ruled the eighties mainstream media of my childhood; that era’s headlines really slavered over androgynous musicians, with churning desire and fear. Smash hit talents like the devastatingly pretty Boy George faced acrid homophobia; powerfully vocal, visually adventurous women like Grace Jones or Annie Lennox were labelled “scary” or “crazy”. Lennox became one of my all-time favourite artists; the steely soul of her voice has accompanied captivating artwork, including her female/male guises in videos including “Love Is a Stranger” (1982) and “Who’s That Girl” (1983), in which the ultra-feminine Lennox shares a kiss with her macho, unshaven alter-ego.

When I interviewed Lennox in 2013, she reflected on the challenges of confronting a “masculine” industry. “I was provocative and I wanted to make people think about gender issues,” Lennox told me. “But it was actually tough being called a ‘gender bender’ because the press often used it as an undermining insult. The orientation of my sexuality was constantly up for grabs. My statement was actually about the lack of power of women. I stood next to my partner in Eurythmics as an equal.” By the time I became a music journalist in the 1990s, “lad culture” was at large in Britpop and even club genres like big beat; female artists were lauded as “ladettes”.

Music, at its best, doesn’t just inspire us to grow into our own skin—it reveals myriad skins: masculine, feminine, someone else entirely. I caught up with a variety of vital twenty-first-century artists to talk about music and masculinity, and its fascinating state of flux.

The Lover & Fighter

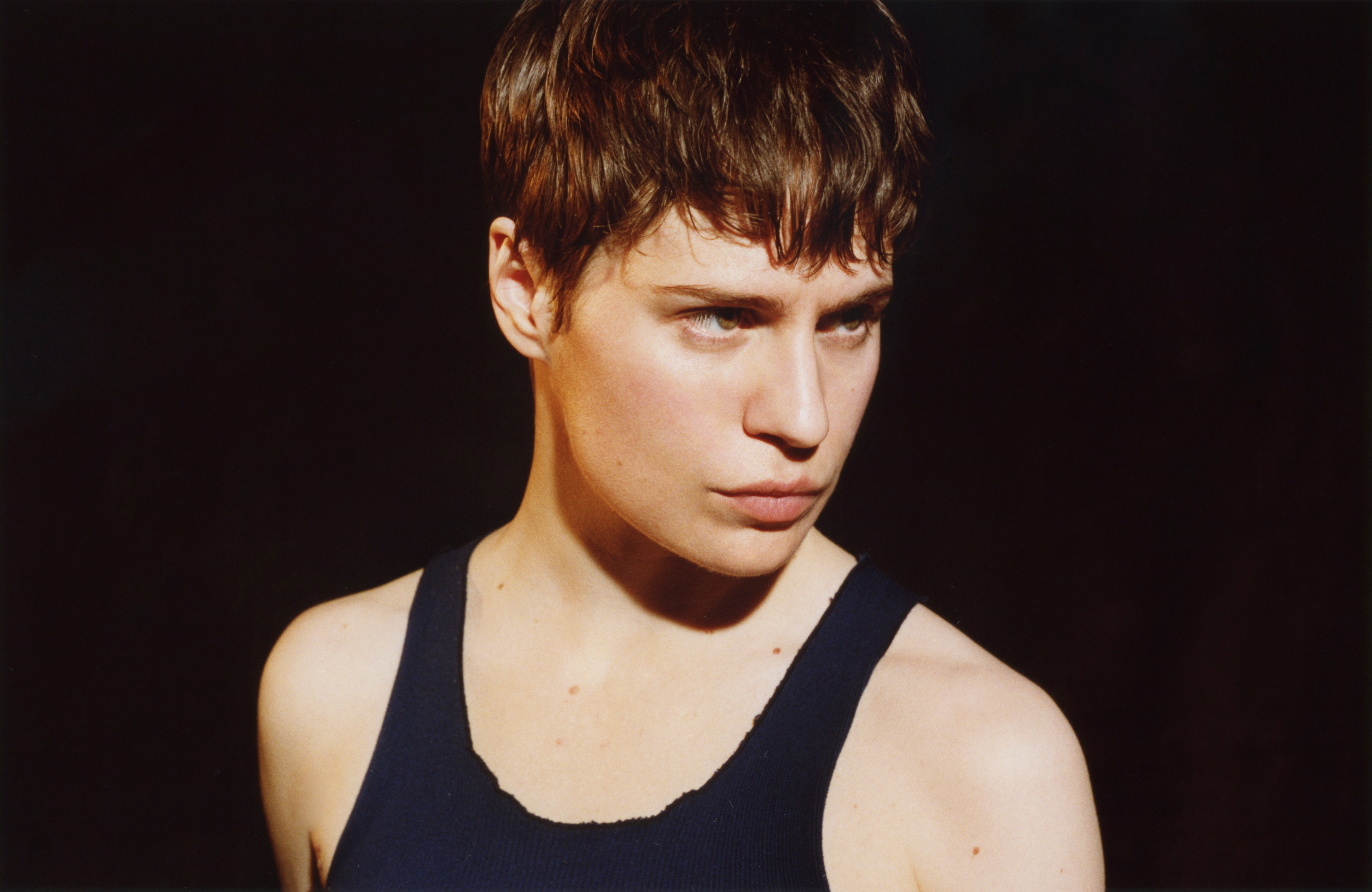

The most brilliant musical highlights of recent times have seen artists harness “masculinity” in thrillingly innovative ways. British singer-songwriter/guitarist Anna Calvi

’s exquisite third album Hunter has summoned both an elemental force and a fearless vulnerability in its tracks (and exhilarating accompanying videos) including “As a Man” and “Don’t Beat the Girl Out of My Boy”. French singer-songwriter/dancer Christine and the Queens (aka Heloise Letissier) restyled herself as a boyish heart-throb on her potent and playful second album, Chris.

“The most brilliant musical highlights of recent times have seen artists harness ‘masculinity’ in thrillingly innovative ways”

“I wanted to express a sense of liberty and freedom on Hunter, because the album is wilder and more visceral,” explains the soft-spoken, sharp-witted Calvi. “I didn’t want to be so ‘perfect-looking’. As a woman, you’re told that your biggest power comes from what you present visually; I think with men, it’s considered more about what they do—but the power of a flesh-and-blood woman is rarely represented when it’s men telling the stories.”

Growing up, Calvi recalls sensing a “subliminal message” when she discovered the work of punk poetess, and Robert Mapplethorpe muse, Patti Smith (“This was a real woman who’s not afraid to express sexuality about desire and wanting, and not just receiving”). When Calvi later emerged with her self-titled 2011 debut, she earned serious acclaim, yet still found herself pushing aside crass interview questions (“How does it feel to play a phallic symbol?”).

Calvi is a fiery presence in her latest videos and mentions that she worked with choreographer Aaron Sillis to create a heightened sense of physical freedom. However, she does not appear in the stand-out visuals for Hunter’s title track; in this intensely tender film (directed by Matt Lambert), the focal points are two non-binary performers.

“Matt [Lambert] and I were talking about how from a queer perspective, exploring your body and pleasure is almost an act of defiance, because we grow up in a society where presenting your natural urge is shameful,” says Calvi. In “Hunter”, love genuinely conquers all; the elegant strength of these expressions also contrasts boldly with the overblown, gung-ho machismo that still looms in the mainstream:

“Donald Trump is the extreme of the toxic, perverted caricature of masculinity,” says Calvi, although she adds: “It feels like the last gasp of this kind of trope: that male-centric power could save us, even though it couldn’t be more unsafe for the world. It’s funny that it co-exists simultaneously with more rounded depictions of men in music; acts like Years and Years [fronted by vocalist Olly Alexander] show that strength doesn’t have to be macho.”

The Rebellious One

Soweto-born MC/singer-songwriter/electronic producer/visual designer Spoek Mathambo stands out as a self-styled renaissance man. His international breakthrough came with 2010’s Mshini Wam album, including his surreally dapper take on Joy Division’s “She’s Lost Control”. His visuals have flowed through B-boy hipness, Afro-centric sci-fi and nightlife energies in turn.

Mathambo recalls that his concept of “masculinity” was shaped during his youth in eighties and nineties South Africa: “General societal and ‘traditional’ mores, as well as my father and brother being my main role models, reared me on sentiments like ‘boys don’t cry’ and ‘be ready for a fight’,” he says. “Added to that, I spent seven years in an Anglican Boys’ School, where there was a kind of quasi-military culture based on conformity, homophobia, rule of violence and ‘discipline’. My rebellion came in the form of hip hop, so I also grew up in the hyper-machismo of hip hop culture.”

Prince’s Purple Rain album represented a rite of passage for the teenage Mathambo: “Prince’s music completely flipped my mind about what could be done with the paradigm of masculinity and expression of sexuality. It made me understand a more sensitive, fluid, inclusive, disruptive expression of my masculinity.”

That unruly force surges through Mathambo’s own works, though he also points out that even the seemingly heavyweight codes of masculinity from “traditional” hip hop to rock have transformed in unpredictable ways.

“Look at rock’s shift from psychedelic frilly shirts to leather pants and screaming, to spandex and big hair, to skinny jeans and eyeliner… it’s not necessarily consistent with hard rock machismo. The same for hip hop… the most superficial expression of masculinity/femininity is dress code, and that always changes. Although I’m not sure if attitudes completely change…”

“Few bands sound as well-muscled as German industrial metallers Rammstein, who have always smashed through traditional masculine codes”

There’s a kind of masculine maelstrom stirring up here. On one level, hip hop might retain its rep for macho posturing and butch street style; on another, we have modern players such as Tyler, the Creator getting confessional (and displaying Eric White’s pastoral painted artwork) on 2017’s Scum Fuck Flower Boy album. Atlanta hip hop/trap star Young Thug modelled a chic couture dress on the cover of his Jeffery mixtape (2016)—though he was caught making misogynist rants at two black female airline workers that same year. Hip hop is now beginning to embrace a much broader spectrum of masculinity and sexuality, thanks to LGBT pioneers including Mykki Blanco

and the Paris-based Kiddy Smile (a strapping figure and baritone vocalist with roots in the vogue house scene).

Elsewhere, few hard rock bands sound as well-muscled as German industrial metallers Rammstein, who have always smashed right through traditional masculine codes. As ostensibly straight men, they stripped naked and oiled up in the video for their 2006 single “Mann Gegen Mann (Man Against Man)”, while their spiky 2009 satire on sex tourism, “Pussy”, featured an even more explicit Jonas Åkerlund-directed video. Rammstein’s previous live shows included frontman Till Lindemann performing “Pussy” while astride a giant “penis” cannon: an OTT ubermensch, spurting foam over the crowds. As Rammstein’s drummer Christoph Schneider once told me in an interview, the band’s motto is: “Do your own thing. And overdo it!”

The Alpha Personality

The music industry is notoriously ruthless: it promotes the notion that any aspiring artist would need to “man up” if they’re intent on making it big. Take Madonna as the pushy pop dominatrix, or Nicki Minaj playing her evil “twin brother” Roman Zolanski (on whom she performed an exorcism at the 2012 Grammy Awards).

Even now, there’s still a sense that female voices remain strangely under-represented in music, so it’s always refreshing to hear outspoken expressions from the likes of Leicester dancehall/rap talent Trillary Banks, whose latest single “White Hennessy” follows her bashment anthems “Come Over Mi Yard” and “Pepper & Spice” (with Inch from London collective Section Boyz). Banks’s visuals are as assured as her vocal delivery: bold and glam, even against everyday backdrops.

“I was never told outright that it’s a masculine industry, but I could see for myself that there weren’t many female artists let alone female rappers out there, and I had to work out for myself why,” admits Banks.

Braggadocio and misogynistic lyrics remain rife in music, but Banks disagrees that female rappers are pressured to adopt masculine codes. “I think we are just conditioned to assume that confidence, ownership and assertiveness are masculine traits when they are not,” she replies. “I am confident, I know what I like and what I want, and that comes across in my music. I know my worth and I speak my mind openly.”

The Brave Heart

About a year ago, British singer/rapper Jordan Stephens, aka half of jocular hip hop talents Rizzle Kicks, published a surprising think-piece in the Guardian newspaper, entitled: “Toxic Masculinity Is Everywhere. It’s Up to Us Men to Fix This”. The feature was intensely personal, and it struck a resonant chord; here was a successful young male admitting fragility and baring his soul. It’s a stratosphere away from the OG masculinity of artists like 50 Cent (who once declared: “I have every feeling that everyone else has, but I’ve developed ways to suppress them. Anger is one of my most comfortable feelings”). It also feels like a crucial move, in an era where numerous high-profile suicides have highlighted the issue of masculinity and mental health.

“In twenty-first-century music, masculinity doesn’t merely denote power or privilege; it evokes questioning and responsibility”

Stephens is a self-confessed dreamer, but he’s also straight-talking; he chats about how he idolized the single mother who raised him, as well as the suppressed rage he felt as a teen. “How I experienced masculinity was very different; I chose not to fight, but as a teenager, I ended up having anger management in football,” he says. “As I grew up, I was always very aware of women, but I was also a dickhead to every girlfriend I’ve had. Anyone who tried to step into my intimate space would have a tough time.”

In twenty-first-century music, masculinity doesn’t merely denote power or privilege; it evokes questioning and responsibility. It resounds through an array of new gen expressions—Stephens’s soul-searching grooves (and rootsier imagery) as Wildwood; Alexander’s triumphant speech at the GQ Awards (“Let our men be happy, be sad, be non-conforming, be feminine, be masculine”); in organizations like Bollywood star Farhan Akhtar’s MARD (Men Against Rape and Discrimination—“mard” is also the Hindi word for “man”).

“The whole masculinity thing is so baffling to me… I feel like it’s about being direct, more than anything,” says Stephens. “We’ve lost sight of the beauty of masculinity, and that has to change, because masculinity is fucking beautiful—it’s assertiveness, protectiveness, the idea of being grounded. Men’s lives will be saved if that’s understood.”

This article originally featured in issue 38

BUY ISSUE 38