Marc Vallée is a London-based documentary photographer whose work on contemporary youth culture has spanned over two decades. From his early years as a skateboarder and punk within the city’s queer scenes, his political involvement with photojournalistic work, to documenting graffiti writers for the past seven years, Vallée’s work has consistently explored contemporary counterculture narratives and personal experience.

Today, Vallée’s work predominantly focuses on the lives of people that navigate the margins of the nocturnal landscape, and those often at odds with the structured flow of neoliberal cities. His subjects are often young, male social transgressors; from graffiti writers and sex workers to activists and urban explorers, they disrupt the capitalist system while in pursuit of their own desires and identities.

The fleeting way in which these individuals drift in and out of Vallée’s lens is a testament to his empathetic eye as a documentary photographer. He himself is found at the heart of his photographs; relationships and friendships manifest in the autobiographical nature of the images, where private and public worlds meet.

Vallée’s latest zine, Number Thirteen, brings together the strands of his subjects shot over the last few years in London, Paris and Berlin. As a farewell to photographing graffiti writers, the publication reflects on a personal and collaborative experience within a time when our actions feel more mediated than ever before.

What led you to your interest in becoming a photographer, as well as your early political involvement growing up?

I was raised in West London and my two strongest subjects at school were art and sociology, which is pretty much a testament to everything I’ve done since. I was a skinhead as a teenager, listening to two-tone ska music and fighting the National Front in my area. I dropped out of sixth form and was very politically active in the late 1980s, working for a left-wing newspaper called the Militant. I was a layout artist and typesetter for them for five years. I learnt so much there, creatively and politically, that it put me in good standing for the rest of my life.

In the early 1990s, I got accepted into art school as a painter but after the first term, I did a photography workshop and was hooked. I then landed a summer job in 1995 at an arts camp in South New Jersey teaching photography. I was visually stimulated with the surf and skate New Jersey coast style. I documented it all on black and white film, processing it in the darkroom at the camp.

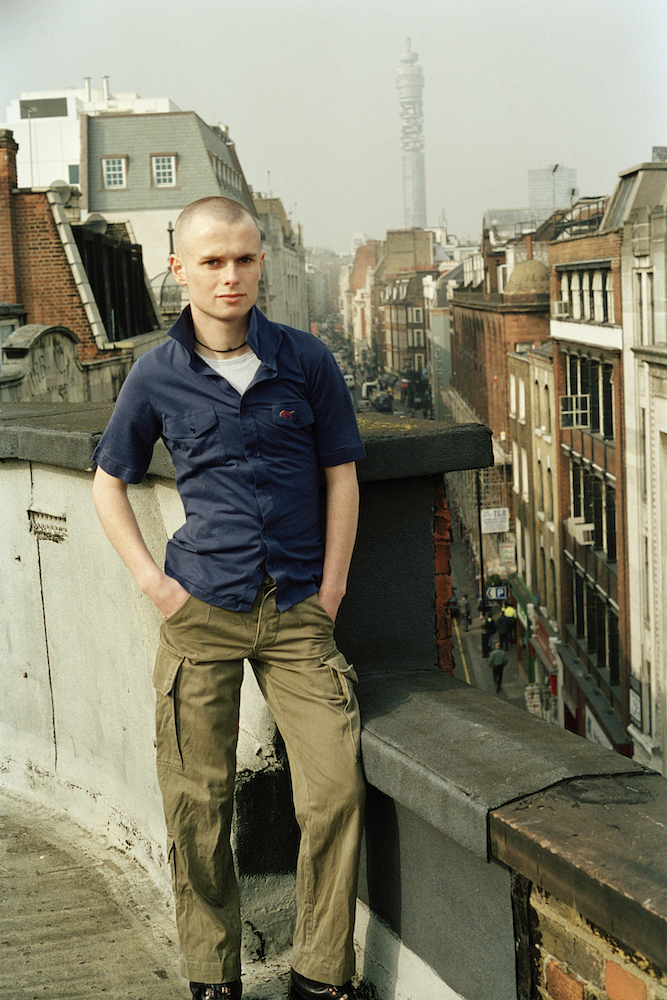

- Graffiti writer on a roof on Wednesday 21 October 2015 in London, England © Marc Vallée

“I was working on investigations about police surveillance and secret police databases on journalists, protestors and environmental activists”

Were you photographing the political landscape of London back then as well? How did your work shift into more of an activist practice?

It was all very autobiographical at the beginning, documenting my world. I remember doing an interview at the time and was asked, “Why isn’t your work political?” I said, “Of course my work’s political, it’s contemporary youth culture.” It got me thinking and soon after I started photographing the anti-war protests during the Blair Era. I started photographing it as a participant who happened to have a film camera, which didn’t really work, so I switched to digital with the aim of documenting protests more seriously.

That went on until about 2010, during which time I documented hundreds of protests, mainly in London but also in other parts of the country. That work pushed me into a photojournalist frame of mind. I was filing pictures for editorials and newspapers but also working on investigations for The Guardian and The Financial Times about police surveillance and secret police databases on journalists, protestors and environmental activists.

How did your background of documentary and photographic journalism influence the way that you were documenting subcultures?

In a way, photographing the protests was a disruption on the original journey, but it was a disruption I don’t regret. I regret getting bashed up by the police and being targeted by fascists, but thankfully I’m not part of that world anymore and I’m back to doing what I did before. The tail end of it was photographing the student protests against the rise of tuition fees and the coalition government that came into power with the Tories and Lib Dems in 2010. I started wrapping it up and essentially moving back to what I was going before, which is when the graffiti work started.

What led you into documenting smaller networks of subcultures like the graffiti world?

I didn’t come from the graffiti world but there’s a link of disruptive, dissenting culture that I found within it. I started documenting the legal wall on Leake Street under Waterloo Station for a couple of years and got to know the writers who went down there. My interest was in documenting the writers, not so much the actual graffiti, so I soon wanted to document the illegal writers. I reached out in multiple directions to find a London crew that would let me photograph them. I eventually found a young crew that allowed me to photograph them for a year which then became the publication, Vandals and the City.

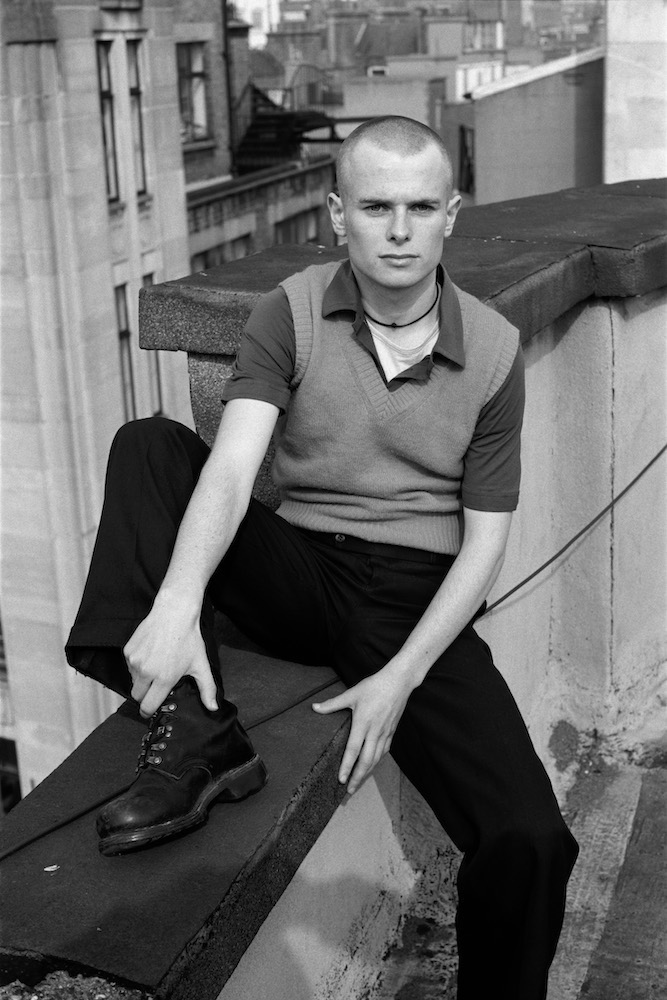

- Alex on Friday 8/Saturday 10 November 2019 in Paris, France (left); A graffiti writer on Friday 09 November 2018 in Paris, France (right). Both © Marc Vallée

What was it about graffiti writers that held the most intrigue for you? You started shooting in black and white and during the night, which was a shift from your usual style of working…

I find it inherently political in the way writers—the archetypal young male—are disrupting the city. There’s a romance to that disruption, it’s a kind of romantic gesture or notion but it has a harder political edge, a physical presence within that space, capturing the writer at that moment in time. It’s also the intellectual discourse or creative outlet or the activity, the thing that they desire, the action. Of course, it’s not exclusively a male youth culture, you have fifty-year-old men who write graffiti and one of my favourite writers, Lady K, walks around Paris in her summer dress in the middle of the day painting walls.

It’s telling a story also. You’re not trying to tell a story of London, it’s three cities, and the story of yourself interacting with these different people who you’ve met by the act of being a photographer…

It’s documentation and it’s collaboration and it’s autobiographical. I’ve not said this before, but in a way, it’s my response to Brexit. I don’t want this to be categorised as my response to Brexit, but it is about these creative, collaborative, transgressive cultures, full of dissent; over time we’ve got to know each other and collaborate, having made work together in London, Paris and Berlin. The photographs document what we do culturally, creatively, artistically in all three cities. It’s interesting that the work was made in the process of the UK leaving an economic and political organisation, with our freedom of movement soon to be disrupted in the future.

“I find it inherently political in the way graffiti writers—the archetypal young male—are disrupting the city. There’s a romance to that disruption”

In light of the last six months with Coronavirus, there have been major changes: the call for the abolition and defunding of the police, the threat and closure of collectively run spaces. All these things are impacting us locally and globally; what effect do these have on subcultures?

The starting point for me would be my memory of being a teenager in the 1980s under Thatcher’s Britain with economic recession, the introduction of neoliberal policies, privatisation, strikes and the militarisation of the police. If we’re having an economic catastrophe and political repression and propaganda from the right, what happens to alternative young creative people in that environment? Well, maybe we’ll have some good music. Punk came out of something. Maybe we’ll have amazing art that will come from it because people will be fighting. There’s optimism and it will be amazing to see how that works. There’ll be a blossoming of DIY culture, putting it back together ourselves the best way we can, and hopefully with solidarity to support each other.