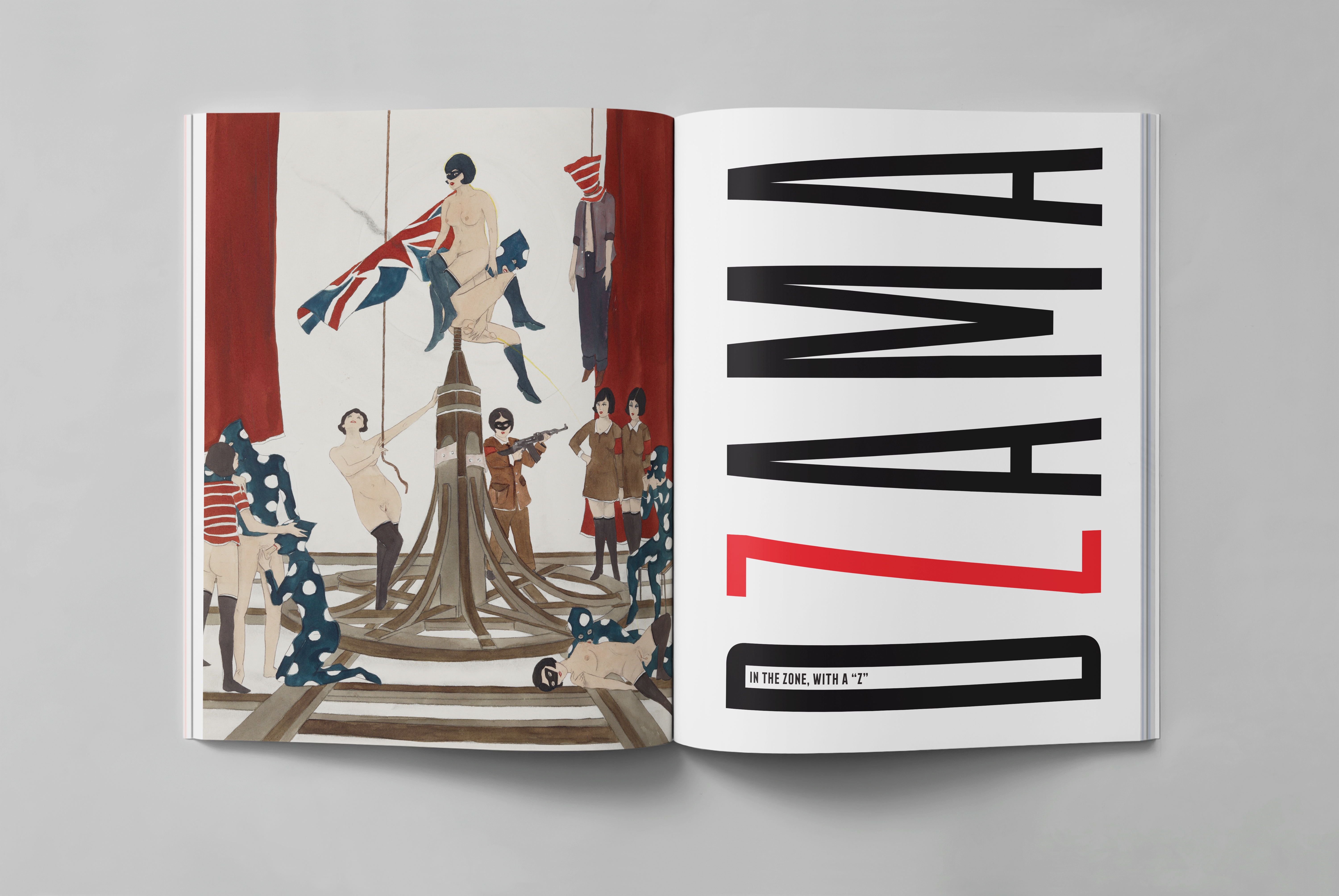

Time is collapsed in Marcel Dzama’s drawings as exotic figures from fairytale, mythology, history and art history collide in a carnivalesque pageant filled with violent ritual and erotic acts that have no rhyme or reason. The artist has garnered international acclaim for his richly inventive iconography, which has spilled into paintings, sculptures, dioramas and films, and spawned multidisciplinary collaborations with the likes of Spike Jonze, Bob Dylan and Dave Eggars. Last year he added a new string to his bow, designing the costumes and sets for a high-profile New York City Ballet production with resident choreographer Justin Peck and Bryce Dessner of indie rock band The National.

Dzama’s latest project is something of a departure—a film he describes as a “full-blown satire” about the art world and himself as an exaggerated celebrity artist. Called A Flower of Evil and riffing on Charles Baudelaire’s influential poetry volume, it will star the actress and comedian Amy Sedaris as a crazed, egotistical Dzama, who is haunted by nightmares that come to life, while regular collaborator Raymond Pettibon will play art dealer David Zwirner and actor Jason Grisell take the part of Pettibon. A sort of film within a film, the action is documented by a “pretentious” art interview programme called “The Artist Stripped Bare”. (All references to Marcel Duchamp are entirely deliberate, of which more later.)

“Key themes are making fun of myself and the world we live in now, with time moving too fast to react to it,” says Dzama, whose open, friendly demeanour is a world away from the frenetic, self-important artist played by Sedaris.

A Flower of Evil grew out of a short video in which Sedaris plays Dzama directing dancers in avant-garde modernist costumes, who perform a ballet routine until she screams “cut” and the music dissolves into disco. For the film’s soundtrack, Dzama plans to enlist his friends in the bands Arcade Fire, Rhe National and LCD Soundsystem, as well as using his own composed material and Sedaris’s voice. If it sounds like the artist is a serial name-dropper, he isn’t; he just happens to have lots of famous mates. The film will be shown in 2018 at his gallery in New York.

“Time moves really differently when you’re drawing, time just disappears… sometimes”

When I meet Dzama, he and Pettibon are busy putting the finishing touches to a gigantic mural for a show at David Zwirner’s London gallery—a dancer in a spotted onesie here, a swirling wave there. The room has been turned into a lifesize comic strip, crowded with superheroes, bats, three-eyed girls and a giant Cheshire cat, against a doom-laden backdrop of engulfing waves and an oil refinery gushing flames that send animals scurrying.

“It’s a bit of a panic. We did the drawing in July in the Zwirner gallery’s garage space in New York and it was breaking records so it really felt like global warming,” says Dzama, who lives in Brooklyn. The exhibition also reflected the apocalyptic mood ahead of the US presidential election. The preponderance of superheroes suggests we need rescuing? “Yeah, exactly,” he grins. (A footnote to that: the artists have recently released their fourth zine, entitled Illegitimate President

, with a dictatorial bull figure on the cover, riffing off Francis Picabia’s sinister 1941–42 painting The Adoration of the Calf.)

Dzama first worked with Pettibon in 2015, when they made a zine for a book fair at the Museum of Modern Art’s outpost PS1 by improvising on each other’s drawings in the mode of the exquisite corpse game beloved of the Surrealists. The pair are generous collaborators, assimilating each other’s motifs so you almost can’t tell who drew what. The appeal for Dzama of collaboration lies in the “freedom to disappear and experiment a bit more, it just opens up everything”. Plus, he notes, “Drawing on my own is kind of lonely.”

Drawing has been Dzama’s mainstay since he was a child growing up in Winnipeg, where the freezing temperatures kept him inside. It was a lifeline at school; he did poorly academically as he was dyslexic but it went undiagnosed for a long time.

So where did his extraordinary image bank come from? One imagines him poring over encyclopaedias or listening rapt to fantastical tales told by his mother. In fact, he confesses in his deadpan way, he watched a lot of television as both his parents worked. “That was like my babysitter. I was like a latchkey kid, so I’d come home, microwave something and watch cartoons with my sister.”

But that’s far from the whole story. Dzama’s father was a big fan of military history and the Winnipeg Art Gallery had one of the largest collections of Inuit art, so those were important influences. Also significant was a long sojourn with his grandparents in a small rural town, which accounts for many of the moose, bears and other wild animals that inhabit his early work. The cowboy figure comes from the same period. “Everyone was heavily into country music and they wore cowboy hats to school. I was this skinny kid with Sid Vicious hair who was really into punk rock, so I felt like I had zero masculinity,” Dzama laughs.

Dzama’s surname is East European, from his father’s side, which is where it gets complicated. Dzama’s grandparents split up temporarily because of his grandfather’s alcoholism, during which time his grandmother had an affair and produced Dzama’s father. “He doesn’t know who his father is… And so I have this mystery side,” says Dzama. The surname came from the alcoholic, who is no blood relation to the artist but, he says, “The name Dzama’s good. It’s nice to have a ‘z’ in it.”

He’s particularly fond of his first name, which he shares with one of his heroes, Marcel Duchamp. This discovery prompted a long-standing fascination, which intensified after Dzama saw Duchamp’s famous nude-through-a-peephole installation Étant Donnés at the Philadelphia Museum in the early 2000s. “That definitely set me into making dioramas and installation pieces or assemblages, and then from there I just wanted to know everything about him,” he explains. “I just loved what he said about art and he felt like this trickster in the art world. I’ve always been obsessed with the mythology of the trickster figure.”

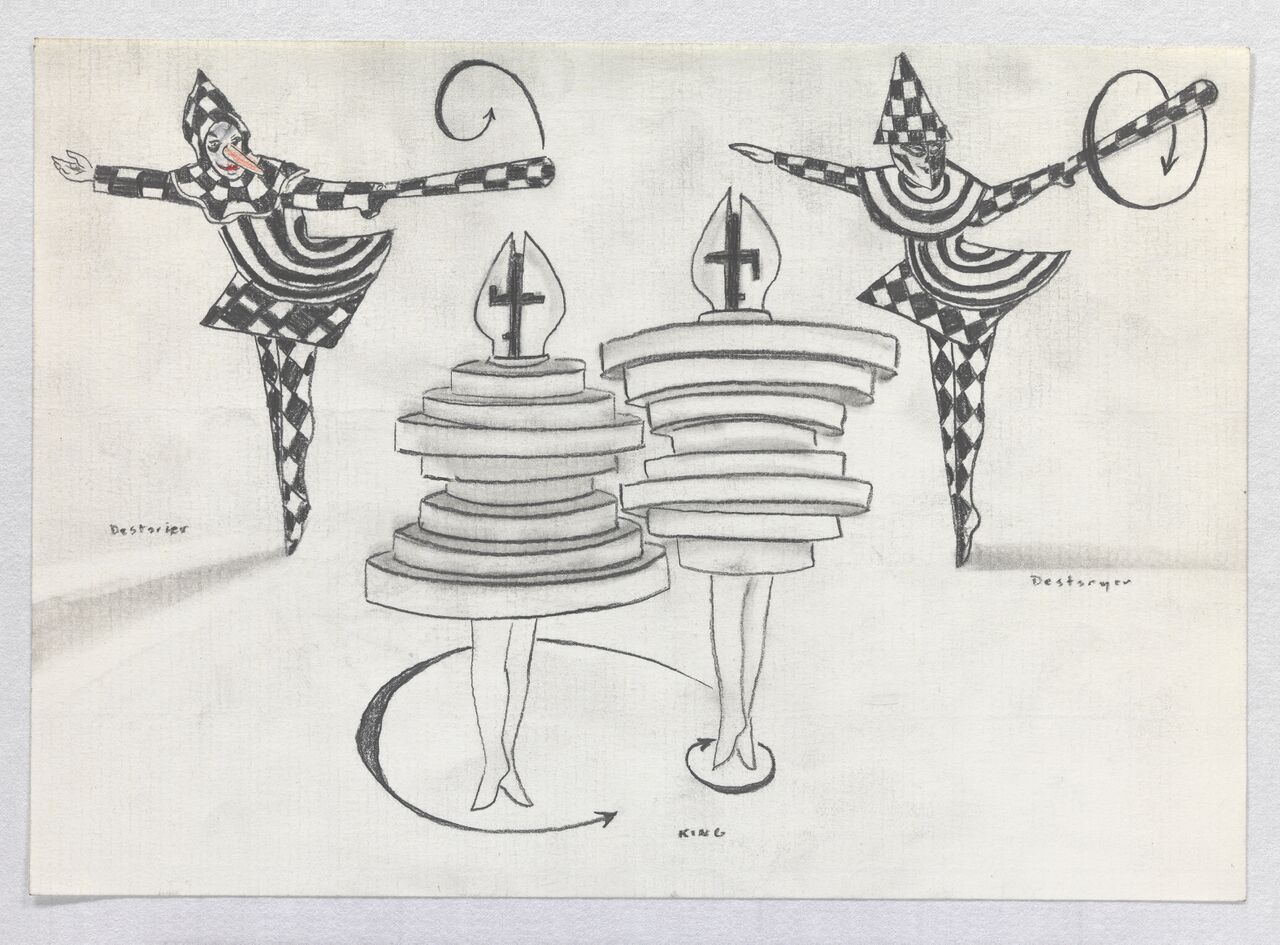

His Duchamp infatuation has manifested itself in chess-themed motifs across his often surreal work and culminated in his dreamlike film Une Danse des Bouffons (2013), which animated the sprawled nude in Étant Donnés and spun an elaborate tale of love and redemption, good and evil, around the characters of Duchamp and the Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins.

“I’ve always been obsessed with the mythology of the trickster figure”

In this “Dadaist love story” Maria is eventually reunited with Duchamp after an ordeal involving an impish trickster, various masked characters, a maniacal clown and again the Picabia-inspired bull-headed authority figure, which gives birth to Duchamp from a vagina in his chin. “I referenced all my favourite pieces of art by Duchamp and Picabia. Those moments when it all came together I felt like I met them… It’s almost like a collaboration,” says Dzama.

His homage continues in his new film A Flower of Evil, in which the Sedaris artist figure has more than a hint of Duchamp’s female alter ego Rrose Sélavy. But his dialogue with art history extends beyond Dada and the Surrealists to Bosch, Goya and even the Russian Constructivists.

Dzama’s interest in collaborating with artists of the past and present goes back to his days as a student at the University of Manitoba, where he co-founded a collective of fellow creative types, who eschewed self-promotion and made drawings together that were never signed.

However, any hopes of remaining anonymous were dashed when Zwirner saw a show of Dzama’s in 1998 and signed him up, aged just twenty-three. Six years later he moved to New York which had a striking impact on his practice. The artist slaughtered swathes of characters in such rite-of-passage drawings as Making Room for the New Ones (2008), where hunters shoot down animals from the sky. In response to the big city, his scenes have become busier and more theatrical. “Since moving the drawings got very claustrophobic. There were a lot of characters so I almost feel like I’m placing them in order of a stage scenario,” he notes.

You get the sense that Dzama’s fertile brain is constantly drinking in its surroundings and spewing out ever weirder characters. A new one with a foetus head, for instance, emerged around 2012 inspired by the birth of his son Willem.

Right now he’s preparing for solo shows at Madrid’s La Casa Encendida and the Mistake Room in Los Angeles in the autumn. He’s working mostly on drawings for these, as well as a short dance film, possibly a puppet theatre and an interactive shooting gallery.

Puppets, dance, films, installation. His works connect across disciplines but drawing still forms the backbone of Dzama’s practice. “Time moves really differently when you’re drawing, time just disappears… sometimes. It’s like a meditation, like being in the zone. That’s what they say, right?” he laughs.

All artwork images courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

This feature originally appeared in Issue 31

BUY ISSUE 31