To me, Maria Pasenau

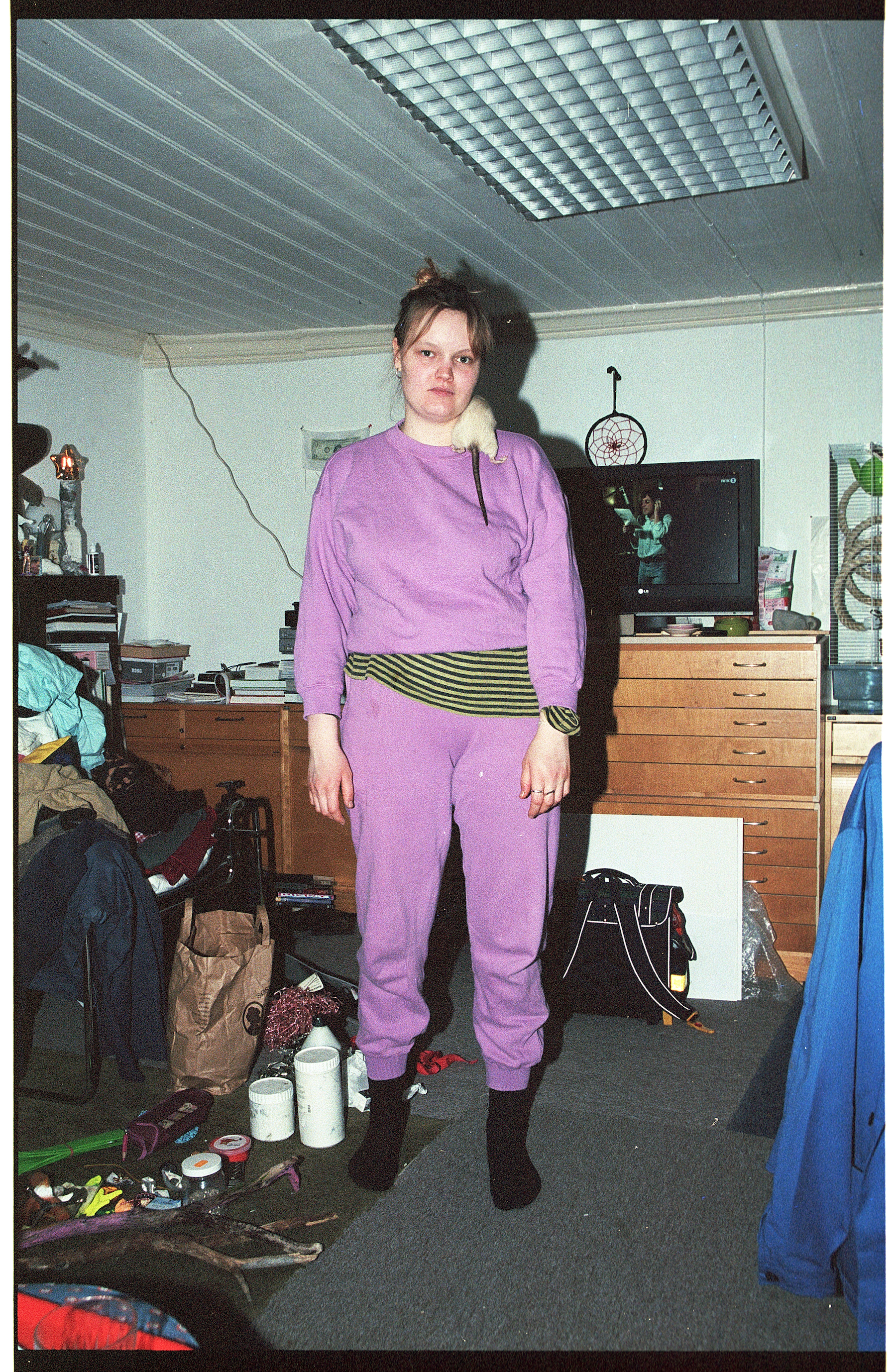

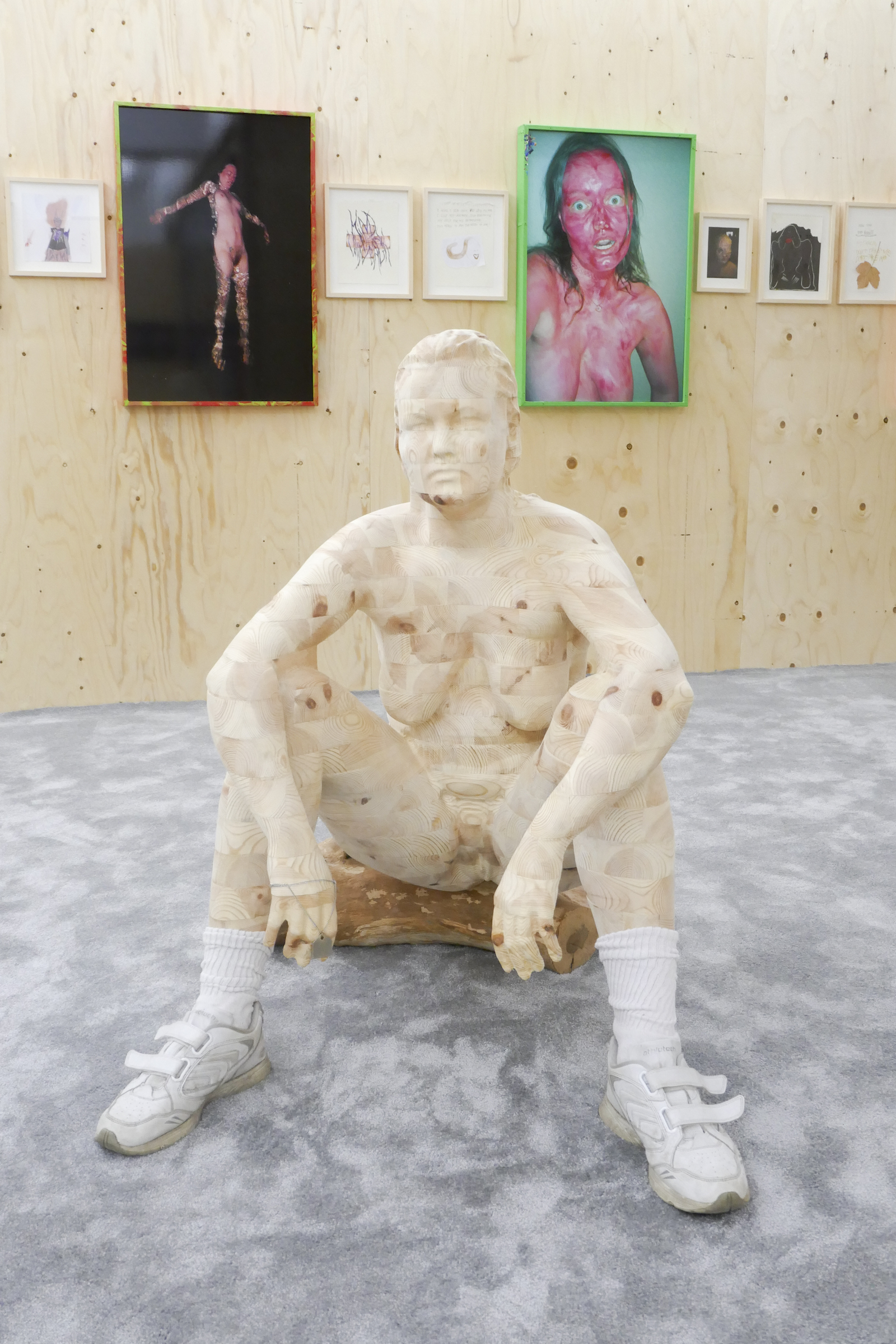

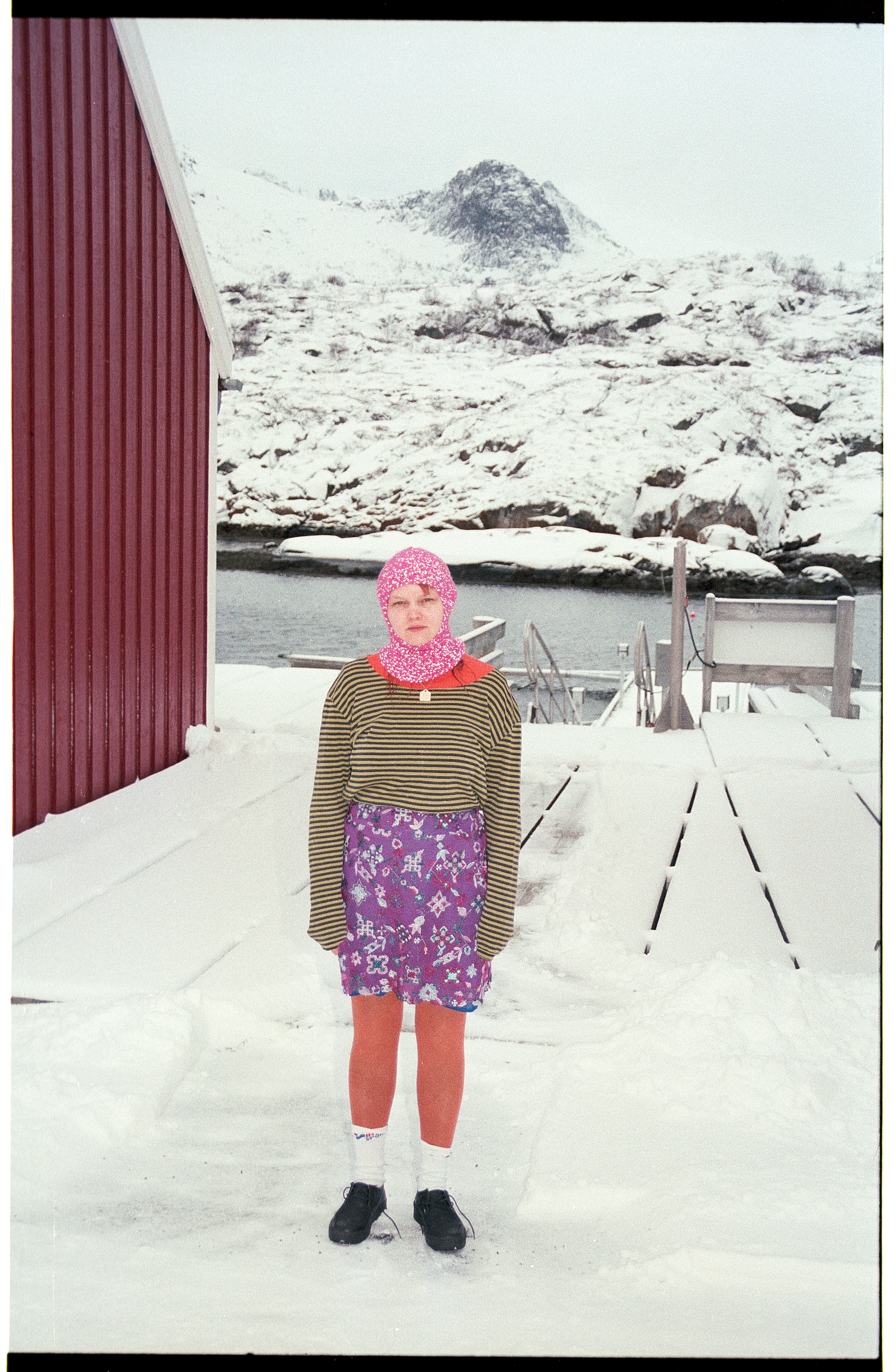

is the artist who created the most memorable portrait of a dildo I’ve ever seen. She captured it after it had been chewed by her dog, and it’s a beautiful image. The young Norwegian artist makes work that’s sexy in a rough way, as full of emotion as a teenager’s bedroom, and punk in its DIY ethos. Her practice is based on photographs but extends to sculptures, installations and raw text works—a no-holds-barred amalgam of her private world, peppered with the people, places and objects closest to her. In her latest work, Pasenau photographed herself every day, for an entire year.

The self-portraits are now on show underground at Piccadilly Circus station in London, in a show called 365 Days of Pasenau curated by Isabella Burley at Soft Opening. It’s an emotional journey through the fluctuating moods and circumstances a young woman inevitably faces today. It might just be the artist’s most personal work yet—and in Pasenau’s case, that’s really saying something.

Can you tell me about this latest project, 365 Days of Paseanu, and how the whole thing has come together?

I started when I was in London with a friend, and I just got this idea of taking pictures every day for one year. I wanted to start there, because on travels I really like to dress up; I always pack my best clothes. So it started with the trip and when I came home I took it really seriously. I had three or four alarms on every day so that I wouldn’t forget to take the picture. I was scared of forgetting one because then the whole project would have to start again. Many different people took the pictures for me, but mostly my boyfriend and my tripod. I got bored taking them because they were all analogue, so I did not see them for a long time after they were taken. When we decided to do this show in London I had to scan all of the 365 pictures on very short notice. I was actually a little bit scared of the outcome. It got so personal on a more scientific level. Now you can really analyse my life.

“I was actually a little bit scared of the outcome. It got so personal on a more scientific level”

It is a very intense and personal work, and it’s being shown in a very public space, inside a tube station. Does it ever get too close to the bone?

In this new project I was very curious about the results. What kind of life do I have? Even I wonder that! When I started scanning the images and saw them within a bigger picture, all together, I was really not sure if I wanted to show it. I think this project is the most personal piece I have ever made. It is scary for me to see it all together.

What’s the role of fear and anxiety in your work, as that seems to be something you’ve reflected in earlier projects?

I am, as a person, very scared. I like to question myself, to think differently about things. It’s very easy to die—and it’s also a very normal thing to do, everyone is going to. The death question is an eternal one for me: am I going to be done with everything I want to do before I die? I have taken a lot of pictures while in the middle of crying; crying for me is very beautiful, it’s also a painful situation but it’s so real. Realness is important to me, and in a way, I think that fear and anxiety bring out the truth in people.

You use and display your photography in an unexpected and unconventional way. When did you realize you didn’t want to just take photos and hang them on walls?

Taking photos is part of my practice, but when I started my creative work I was not limited to photography. I started painting when I was small; I’m dyslexic, so making something that was an object to describe things in my own way enabled me not to just read or write text. So when I started taking photos, I used the camera as a tool, I tried different things and had a lot of fun with it. To take pictures is really just to paint with light. To take an interesting photo is very difficult, and I was also really struggling with knowing how to show the photograph in a room. It had to fit with how I imagined it. I wanted the picture to be honoured as much as a painter honours their painting; I really just wanted to take photography seriously. So I experimented with how to show the photos in the perfect way.

“I have taken a lot of pictures while in the middle of crying; crying for me is very beautiful”

You’ve had some quite big exhibitions at a very young age, does this come with a certain pressure, while you’re still evolving as an artist? And how does living in Oslo affect the way you’re able to work?

I feel like I could not evolve that much if I did not get the opportunity to show what I have been working on. I have some specific projects that often end in a book and exhibition, and for my process it’s very important that I have an exhibition. I think it’s important that galleries take a risk, and show new and growing artists—where else would they learn how to build themselves? I didn’t get into the KHIO, the art academy in Oslo, so I was forced to just start. I carried on, never stopped and looked back—things are just happening naturally.

I like Oslo a lot, and almost everyone in the art community knows each other. As for art funding, you can actually live as an artist without selling anything of your work, you just have to be really good at writing applications. For me I think it’s important to earn my own money, I like to sell and I also have kept a photo store job so I can survive on making art. I did not get funding for my first book but that did not stop me from making it; I started a Kickstarter and got all the money in from pre-sales. That drive to do something impossible is important to me and it gives me power.