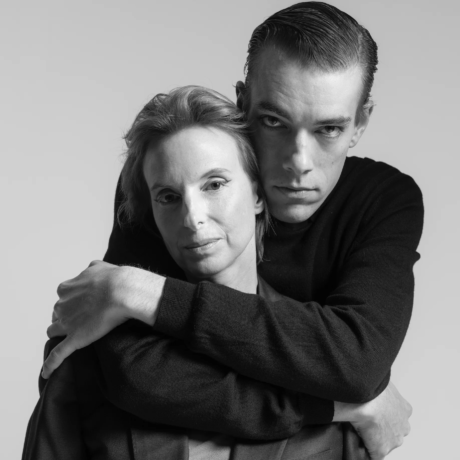

As a new HBO documentary depicts the rise of the Czech-born, NYC-based painter and photographer, and the evolution of the creative collaboration with her partner, Elephant speaks with the lovers about their shared exploration of perspective, identity and belonging, and how their pursuit of art brought them closer than ever.

This isn’t the first conversation I have with Marie Tomanova. Our most dated interview, conducted over email from an Airbnb I stayed at for a week in the Peloponnese town of Nafplio, Greece, marked the release of her New York New York volume in September 2021. The article was my writing debut for a magazine I would go on to collaborate with for nearly four years, though, at the time, I didn’t know that would be the case. I was 23, the world was slowly waking up from the forced slumberness of COVID-19—as showed my late-summer vacation—and in Marie’s spirited, irreverent shots of young New Yorkers, I caught a glimpse of myself carving my way into adult life and London away from Italy, my home country.

A new opportunity to speak with the painter-cum-photographer came with the publication of It Was Once My Universe, her third book, in the autumn of 2022. Between that time and our first interaction, we had stayed in touch and developed an appreciation for each other’s work. That’s why, when Marie asked to collaborate on another story, I didn’t hesitate. My second write-up for one of the publications I still admire most today, the piece went live on October 5 of that year. In that umpteenth, typed-out exchange, Marie and I found ourselves reflecting on her long-dreamed return to the Czech Republic in December 2018, the central theme of her new monograph. We processed the often bittersweet tension between reality and expectation that can arise from idealising ‘home’: a dilemma common to us both as expats who have since established roots elsewhere, and a theme conjured even more eloquently by Marie’s partner in art and life, Thomas Beachdel, in the essay that accompanies the volume.

This April, nearly three years since we spoke for the first time, I finally sat down with Marie and Thomas over Zoom to trace the evolution of her career. Together, we explored how her artistic awakening in New York, coupled with their ongoing creative dialogue, had enabled her to come into her own. Although we had never met in person, reconnecting felt like going back to an old friend—and a good one, too. In the intervening years, Marie and I had grown, both personally and professionally. Projects had surfaced, materialised and concluded, but it’s works like her recent photographic and audiovisual series, 5 East Broadway—a playfully intimate, ‘moving’ portrayal of NYC youth—that remind us of what makes her craft so resonant, and what it renders best: the disorienting limbo between adolescence and adulthood, and the intricate physical, emotional and psychological metamorphosis that unfolds within it, as Marie and Thomas recount below.

Gilda Bruno: What did your life look like up until the moment your paths intertwined?

Marie Tomanova: I come from Mikulov, a small town in Czech Republic, and I studied painting. My years in college were rough because there was no support for female artists to speak within an all-male faculty, whose perspective was clear and present at all times. After graduating with a Masters of Fine Arts Fine Arts from Brno University of Technology, I felt like there was no future for me as a painter there—or anywhere for that matter. I was at a loss, and moved to America without knowing where I was heading, what I would be doing. I spent my first year in North Carolina and the second one in Upstate New York. I wasn’t painting or taking photographs; I was just writing a lot. When I eventually moved to New York—and I think it was destiny, not a coincidence—I met Thomas. I was at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, standing in front of Gauguin’s Two Tahitian Women (1899), when he said “hello” to me. I was rather surprised, and sort of dismissed him [laughs]. A few minutes later, I saw him walk around with a group of people, giving a talk, and realised that was what he was doing. So, I joined, and he let me listen to his lecture.

I was inspired more than I had ever been while hearing about art during classes in university. The way he connected artworks from different eras and times and found threads connecting them all blew me away. It was fascinating. At the end of the tour, I asked him for his phone number in front of a group of women who had taken part in it, and he gave it to me. It was March 2012, and that was the beginning of everything. For our first date, he took me to the Guggenheim Museum to see the first comprehensive survey of Francesca Woodman’s work. They were showing her photography, alongside excerpts from her journals. Having done a lot of writing myself the whole year before as well as throughout my youth, I instantly connected with her work. It made me think, “why have I never tried photography?” The same month, I signed up for evening classes at NYC’s School of Visual Arts. After each class, I would meet Thomas, he would look at my pictures and critique them with me, having long discussions about art. He became the first supporter of my photography, and here we are 12 years later—and it is better than ever.

Thomas Beachdel: As an abstract maths college major, one day I came across this 19th-century mathematician called Henri Poincaré, who was hired to adjust all the clocks on the French railroad system. If the clock was set to noon in Paris, in Dijon it wouldn’t be in sync because of the time that it took for the electrical signal to travel between the cities. According to Euclid’s fifth theorem, straight lines never cross, but Poincaré said they do if you define them as being on a torus—two donuts put together like an infinity symbol. That showed me the extent to which what you hold true depends on your perspective. From there, perspective became this meta concept I felt the urge to dig deeper into.

Another eye-opening read was French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, who said that, though you can quantify heat, fire itself is immeasurable; it’s the creative spark. It’s Prometheus. It’s special. To me, fire and non-Euclidean geometry embodied an epistemological break, or a moment of rupture that separates science from its non-scientific past. That was enough to convince me to switch from abstract maths to art history: until then, I had tried to prove theorems. Art provided me with an escape; a way of looking at things differently. Today, besides working on my books on 18th- and 19th-century art, I am a professor of Art History at New York’s Hostos Community College in the South Bronx, a bilingual institution providing higher education for the people in the community.

As for Marie, she always says she started photographing in New York in 2012, but already in her teens, she was taking photos on her cell phone and a little digital camera, proving she was a photographer from a much earlier time. We have done a couple of exhibitions on visual material from those years, the most recent one being Nothing Compares To You, which ran at Brno’s OFF/Format Gallery in the summer of 2022 and included a series titled Youth is Dark—thousands of low-res images that are simply unbelievable. A couple of them have already surfaced in other works of Marie, like Peter (2011), for example, which appears in the introduction to her Young American book. Seen as a cohesive project, they are remarkable: 2005—2011 is the date range of those images, and that’s when she actually got into photography. It had nothing to do with me.

MT: I only started to feel like a photographer once I acknowledged photography as a medium through which to express myself, but Thomas is right; I was taking pictures way before moving to the US, and even more passionately than painting. I would snap photos of my best friends, lovers, breakups and difficult relationships I was going through, the dancing and drinking parties we held in our small town until morning hours—everything is in those images. It is a very raw, emotional collection of pictures. They weren’t shot to be seen, either, but to keep the memories alive for longer. There was no Facebook nor Instagram at the time, you couldn’t upload images. It was a radically different time, and mindset. Those were private photographs shot for myself only.

TB: And there are a lot of selfies in that early work, too. Despite it being ‘pre-selfie’ era, Marie was obsessed with self-portraiture, and I am very excited about this portion of her work having finally been revealed in her latest solo show, Lost and Found, which continues at New York’s C24 Gallery through November 8.

MT: As the youngest of three girls, by the time I was born, my parents had no time to take photos. There are very few images of me until I got that phone and began to capture some myself. My interest in seeing myself from the outside probably came as a reaction to the lack of pictures from my childhood. Lost and Found is the newest testament to my ongoing, long-term focus on self-portraiture and identity. It is a very important showcase for me, presenting new photography series and, for the first time in ten years, also paintings. Here, a body of self-portrait canvases and works on paper is on display alongside Three Empty Weeks in July (2022), a photographic series in which I set out to take an instant picture of myself every day for a year beginning January 1, 2022. Though, ultimately, I failed, as I didn’t take any photographs for three weeks in July, rather than being a failure, those empty weeks—those missing puzzle pieces—became an inspiration, a metaphor. They became something greater—they stand in for the images that aren’t shown, the instants behind the camera that cannot be observed, the life and depth of self that is not lensed on film.

The ideas of failure and struggling to find oneself—particularly through work, through art—are an important aspect of the exhibition at C24 Gallery. In addition to showing a selection of enlarged photographs from Three Empty Weeks in July, I inscribed the entire body of work onto the backs of my early paintings. The 344 instant photographs are laid-out as months and photographed on the reverse of 12 canvases that I created 2005—2010, before settling in the United States. The face of the unseen early paintings thus becomes a mystery reinforced by what they could be through their connection with those that I produced for this presentation—a practice that has been revisited starting December 2023. These new painted works are all variations on self, a subject that speaks to a contemporary culture saturated with an obsession with identity.

GB: What specific experiences prompted your US-based photographic experimentation, Marie?

MT: If my early Czech Republic photographs were pure passion, very open-minded and with no real concept behind them, and that was the strength of them, in New York, the trigger came from self-portraiture—prompted by that Francesca Woodman’s retrospective—and therefore from within myself, as I didn’t know any people I could photograph. I was on my own, experimenting with the process and learning what I liked by being in front of the camera, behind it, as well as in the end result. If anything, seeing myself in those first American self-portraits imbued me with a sense of belonging as an immigrant. Shortly after, I started to portray young people in New York, which Thomas eventually helped me mould into shape, giving life to both the Young American (2018) exhibition and the eponymous book, published by Paradigm Publishing in 2019 with a foreword by Ryan McGinley.

TB: While building Young American, Marie was struggling. She would take pictures of herself in the landscape, striving to feel her past, literally, in that earth. Coincidentally, she was also meeting new people and shooting their photographs, connecting with them and their stories through those images. With Trump in power and her undocumented immigrant status at the time, it was a very disturbing time. Marie expected America to be something else, she needed inspiration about what America really was and found it in those young New Yorkers. Young American hence became an antidote to the troubling political situation of that time.

MT: Coming from Eastern Europe, for me, America had always been the place of freedom. All of a sudden, though, Trump talked about building walls, not letting any immigrants in and deporting everybody who was an illegal resident. Of course, that also meant me—I was terrified. That leads us to my next project, It Was Once My Universe, a highly personal body of work documenting my first return home to my family after eight years in the US, in December 2018. After finally receiving my green card, Thomas and I flew to my Czech hometown for Christmas, New Year’s Eve and my mother’s wedding. It was a long-awaited moment for me, and a very emotional one. I knew it was going to be hard; I had waited so long for it and built enormous expectations around it. It is all captured in director Marie Dvořáková’s upcoming HBO documentary film World Between Us, which premiered on October 29 at the Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival in the Czech Republic. Marie has been filming me and Thomas since 2018. She started doing it before my debut solo show, Young American, and has followed us since. I can’t wait to see it on the big screen and share it with the audience. It will be in cinemas in the first half of 2025, and land on HBO thereafter.

But to get back to It Was Once My Universe—the idea was to take photographs every day to have something familiar there, something that I could, after leaving again, hide behind and process my feelings through. Photography was my safe space. I took pictures of my home every day, but it ended up being quite a different experience than I expected. I know every corner of this house by heart; growing up, it always seemed the most boring place. Nothing was interesting about it, and that is what pushed me into wanting to see the world. But returning after those long eight years, I was fascinated by every piece of the household. Nostalgia hit me: I adored how the sunset lights hit the chairs where my mum and stepfather always sit, how special it felt to see it and to actually photograph it. To be there. To be there again. It was magical to see how much my vision of my home had changed. And that’s, again, perspectives, right, Thomas?

TB: It Was Once My Universe was the first project that was set in advance with conceptual intent. Marie knew she was going home for 21 days and decided to document it all in photographs. She had gotten a new camera specifically for that and it had a date stamp, which became an important part of the series—she intentionally left the date stamp on the New York time zone. So the dates and times that are in the photographs taken in the Czech Republic are not accurate; it emphasised this idea of slippage, of places in between.

GB: Marie, you place a lot of importance in the texts part of your visual projects, many of which have been written by Thomas. How would you describe your creative collaboration? How do you go about filling the gaps in each other’s process, whether photographically or in words?

TB: I used to write all of the essays for the books. The first essay for Young American was really more art historical to place it in a clear framework. The second one, which was featured in New York New York, was a little looser and emphasised the idea of portrait, place and the meaning of environment. These texts provide contextualisation through the eyes of an art historian, and there is a lot to be said. Still, by the time the third book, It Was Once My Universe, rolled around, Marie was much more engaged in the text making. So I wrote the essay and Marie wrote her own text for the book, too. Lucy Sante wrote the foreword for that, which I thought was really fitting, especially since Lucy had just transitioned and, for Marie, It Was Once My Universe was all about displacement, or being caught in between.

GB: I am curious to see how World Between Us will do justice to your transformation, Marie, not only as a person and an immigrant, but also as an artist, and how it will retrace your relationship with Thomas from the start.

MT: Marie Dvořáková did a fantastic job with the film: it seemed impossible to me to squish five years into an hour and a half, but she did it, and that shows she is a close friend of ours and that the whole thing is quite intimate. The story is told beautifully from multiple angles—it follows me coming from a small town and finding myself and my passions in New York; what my relationship with Thomas looks like as we work together; but it also narrates my first return home, all of my exhibitions and how, suddenly, hundreds of people began to show up at their openings and my book launches, including all of their reactions. It’s such a beautiful story that, watching it, it almost doesn’t feel like mine.

GB: Did it ever get tricky, all of that being filmed as you tried to work things out?

MT: There were a couple of moments where I struggled with how personal it had all gotten, but in the end, those instants are the strength of it. There is a scene where I talk about my father, who passed away two days before my sixteenth birthday. I had no issue with opening up and sharing things with Marie, but it was tough. Still, I am happy she was able to recount such complex times in my life, and, really, my life with Thomas. She captured my journey from having no career to this and did it in a very human, delicately intimate way. There were also things I had completely forgotten about, which the documentary brought back to my mind. In one of them, Thomas and I are in a cab and I am doubting everything about a big project that was in the works at the time. You can hear me go, “I can’t do this, I am failing”, but Thomas is there to support me. Since we met, he has continually encouraged me, and it shows in the film. I feel eternally lucky to have someone who keeps pushing me forward, and who doesn’t let me give everything up.

GB: Seeing your adult life flash by before you in that way must have felt personal and revelatory, but I can spot a similar tendency in your most recent works, like in the videos gathered in your 5 East Broadway (2023) project; a collection of images and films entirely lensed in a 3,5-metre studio. Despite still zooming in on the reality of NYC youth, this series doesn’t feel as edgy as Young American. Instead, there is something much more subtle about it. It’s more about the people—their lives, hopes and vulnerabilities—than an idealised look at all of that. Am I wrong?

MT: Almost half of the people that I photographed and filmed for 5 East Broadway I have known since the making of Young American, but this specific series focuses on a smaller group of New Yorkers and goes deeper into what I call “extended portraiture”. To develop it, I invited them to come to my studio, situated on the fourth floor of a walk-up building at 5 East Broadway, to take photographs, film and dance. First, we took photos. Then, we filmed. I asked them if they could select their favourite song and dance for me. They didn’t know about the filming part ahead of time, which I think was important because I didn’t want it to feel like any sort of social media dance-off. It was really about capturing and being in the moment. I was like, “what is your favourite song right now? What’s the first that comes to mind?” For some of them, landing on one was hard. Being 20-something, music is such a defining entity. The films have a very intimate feeling—you can hear the fan in the background, the cars from the street and all sorts of New York City sounds.

Some people felt a little shy dancing like that, but it was incredible to see that they didn’t give up, and how it evolved. With others, you could see from the beginning there was a sort of seriousness to them. Still, as the movement got to them, they lit up and shone. You could recognise so much of their personality in how they danced, so much of their culture and where they come from. It is wild to realise how much body language can unveil about us. This film is called Beat of My Heart. And after they were done dancing, I asked them about their dreams and their dreams at night, turning their answers into a second film, 14 Dreamers (I Want to Be the Next Courtney Love…But Better). Both are currently on view as a large-scale projection as part of Grow It, Show It! A Look at Hair from Diane Arbus to TikTok, a group exhibition open at Essen’s Museum Folkwang until January 12, 2025. It’s really exciting to have these films shown alongside works by artists like Diane Arbus, Rineke Dijkstra, Nan Goldin, Ana Mendieta and Wolfgang Tillmans.

GB: 5 East Broadway reminds me of the teenage pictures where you posed in front of the mirror, feeling, at once, seen and unseen, fighting to understand who you were. Hair, in a way, became a signifier of this process: in these photos, viewers witness you go from long blonde hair to a razor-short, shaved head. Again, there is this sense of transition, suspension and awkwardness before eventually being at ease both in front of someone else and with yourself. Perhaps, this project allowed you to experience that process again vicariously through the people represented in it, as a point of departure—or closure—from your early Czech and US years. Now that you’ve done that, what’s next? And, with all of these ideas coming up, how do you two maintain a healthy work-life balance?

MT: We never get fed up with each other, but it is easy to do so with the work. Sometimes I am like, “can we please talk about something else?” Which we achieved…

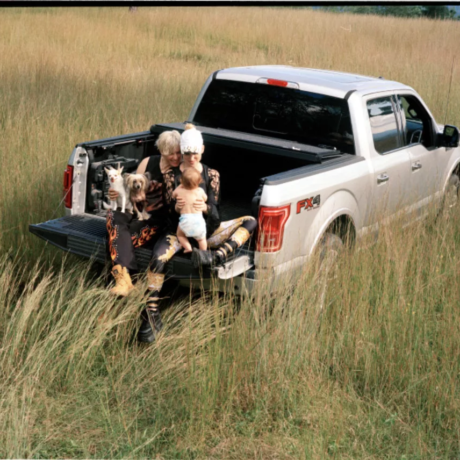

TB: By getting a puppy [laughs].

GB: That’s it—brilliant way out of stress.

TB: In terms of new projects, we are planning an exhibition at the Moravian Gallery Museum in Brno, which, as we discussed earlier, is the ‘site of failure’ where Marie completed her art studies, and therefore holds a special resonance for her. You could say it isn’t a place of failure, but of becoming, of overcoming. That show will open in April 2025, and we are considering doing one on the Three Empty Weeks series, too. Marie and I are also working on a book on her and a fellow Czech photographer, Libuše Jarcovjáková, whose production developed during the country’s communist era: a time of repression, particularly for women and the LGBTQI+ community, of which she is part. It is a dialogue between her and Marie through the lens of self-portraiture. And there are a lot more top-secret projects we still can’t talk about—at least for now.

Written by Gilda Bruno

‘Lost and Found’ is open at C24 Gallery, New York, through November 8

‘Grow It, Show It! A Look at Hair from Diane Arbus to TikTok’ is open at Essen’s Museum Folkwang through January 12, 2025

Marie Dvořáková’s ‘World Between Us’ has just launched at Ji.hlava International Documentary Film Festival, and is set to open in theatres in early 2025 before landing on HBO